Читать книгу In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz: Living on the Brink of Disaster in the Congo - Michela Wrong - Страница 6

CHAPTER ONE You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave

ОглавлениеKinshasa, 17 May 1997

Dear Guest,

Due to the events that have occurred last night, most of our employees have been unable to reach the hotel. Therefore, we are sorry to inform you that we will provide you only with a minimum service of room cleaning and that the laundry is only available for cleaning of your personal belongings. In advance, we thank you for your understanding and we hope that we will be able soon to assure our usual service quality.

The Management

At 3 a.m. on Saturday morning, a group of guests who had just staggered back to their rooms after a heavy drinking session in L’Atmosphère, the nightclub hidden in the bowels of Kinshasa’s best hotel, heard something of a fracas taking place outside. Peering from their balconies near the top of the Tower, the modern part of the hotel where management liked to put guests paying full whack, they witnessed a scene calculated to sober them up.

Drawing up outside the Hotel Intercontinental, effectively barring all exits, were several military armoured cars, crammed with members of the Special Presidential Division (DSP), the dreaded elite unit dedicated to President Mobutu’s personal protection and held responsible for the infamous Lubumbashi massacre. A black jeep with tinted windows had careered up to the side entrance and its owner – Mobutu’s own son Kongulu, a DSP captain – was now levelling his sub-machine gun at the night receptionist.

Kongulu, who was later to die of AIDS, was a stocky, bearded man with a taste for fast cars, gambling and women. He left unpaid bills wherever he went with creditors too frightened to demand payment of the man who had been nicknamed ‘Saddam Hussein’ by Kinshasa’s inhabitants. Now he was in full combat gear, bristling with grenades, two gleaming cartridge belts crisscrossed Rambo-style across his chest. And he was very, very angry.

Screaming at the receptionist, he demanded the room numbers of an army captain and another high-ranking official staying at the Intercontinental, men he accused of betraying his father, who had fled with his family hours before rather than face humiliation at the hands of the rebel forces advancing on the capital.

Up in Camp Tsha Tshi, the barracks on the hill which housed Mobutu’s deserted villa, Kongulu’s fellow soldiers had already killed the only man diplomats believed was capable of negotiating a peaceful handover. With the rebels believed to be only a couple of hours’ march away, Kongulu and his men were driving from one suspected hideout to another in a mood of grim fury, searching for traitors. Their days in the sun were over, they knew, but they would not go quietly. They could feel the power slipping through their fingers, but there was still time, in the moments before Mobutu’s aura of invincibility finally evaporated in the warm river air, for some score-settling.

The hotel incident swiftly descended into farce, as things had a tendency to do in Zaire.

‘Block the lifts,’ ordered the hotel’s suave Jordanian manager, determined, with a level of bravery verging on the foolhardy, to protect his guests. The night staff obediently flipped the power switch. But by the time the manager’s order had got through, Kongulu and two burly soldiers were already on the sixteenth floor.

Storming from one identical door to another, unable to locate their intended victims – long since fled – and unable to descend, the death squad was reaching near-hysteria. ‘Unblock the lifts, let them out, let them out,’ ordered the manager, beginning to feel rattled. Incandescent with fury, the trio spilled out into the lobby. Cursing and spitting, they mustered their forces, revved their vehicles and roared off into the night, determined to slake their blood lust before dawn.

The waiting was at an end. May 17, 1997 was destined to be showdown time for Zaire. And it looked uncomfortably clear that the months of diplomatic attempts to negotiate a deal that would ease Mobutu out and rebel leader Laurent Kabila in, preventing Kinshasa from descending into a frenzy of destruction behind the departing president, had come to precisely nothing.

The fact that so many of the key episodes in what was to be Zaire’s great unravelling took place in the Hotel Intercontinental was not coincidental. Africa is a continent that seems to specialise in symbolic hotels which, for months or years, are microcosms of their countries’ tumultuous histories. They are buildings where atrocities are committed, coups d’état consecrated, embryonic rebel governments lodged, peace deals signed, and when the troubled days are over, they still miraculously come up with almond croissants, fresh coffee and CNN in most rooms.

In Rwanda, that role is fulfilled by the Mille Collines hotel, where the management stared down the Hutu militiamen bent on slaughtering terrified Tutsi guests during the 1994 genocide. In Zimbabwe, it used to be the Meikles, where armed white farmers rubbed shoulders with sanction-busters during the Smith regime. In Ethiopia it is the Hilton, where during the Mengistu years some staff doubled as government informers; in Uganda, the Nile, whose rooms once rang with the screams of suspects being tortured by Idi Amin’s police.

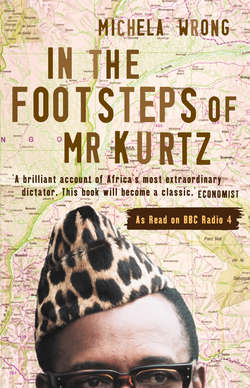

In Congo the honour most definitely goes to the Hotel Intercontinental. I know, because I once lived there. With one room as my living quarters, another as dilapidated office and a rooftop beer crate as the perch for a satellite telex – my link with the outside world – I soon realised that the hotel, as emblematic of the regime as Mobutu’s leopardskin hat, offered the perfect vantage point from which to observe the dying days of the dinosaur.

The hotel was built on a whim. On a visit to Abidjan in the Ivory Coast, President Mobutu saw the Hotel Ivoire, and decided he wanted one too. For once, his impulses were based on canny business instincts. The Intercontinental was the first five-star hotel in Kinshasa. Until the restoration of the Hotel Memling, its rival in the town centre, there was simply nowhere else to go for VIPS seeking the bland efficiency only an international hotel chain can deliver. During the prosperous 1970s, the 50 per cent government stake in the building was a share in a certified cash cow.

Constructed on a spur of land in leafy Gombe, a district of ambassadors’ residences and ministries, it enjoys some of the best views in Kinshasa. To the east, the Congo river traces a lazy sweep as it emerges from Malebo pool, an expanse of water so vast that, venturing out in a small boat, you can lose sight of the opposite banks and end up wondering whether, by some miracle of geography, you have drifted out to sea.

Across the water, which is transformed into a disturbed mirror of silver and gold each sunset, gleams the distinctive concave tower that serves as the city of Brazzaville’s landmark. The river, that concourse Marlow described as ‘an immense snake uncoiled, with its head in the sea, its body at rest curving afar over a vast country, and its tail lost in the depths of the land’ is the frontier, a fact exploited by the fishermen whose delicate pirogues languidly traverse the waterway for a spot of incidental smuggling.

Nowhere else in the world do two capitals lie so close to each other, within easy shelling distance, in fact, a feature that has been of more than merely abstract interest in the past. The proximity allows each city to act as an impromptu refugee camp when things get too hot at home. From Brazzaville to Kinshasa, from Kinshasa to Brazzaville, residents ping-pong irrepressibly from one to another – sinks, toilets and mattresses on their heads, depending on which capital is judged more dangerous at any given moment.

In peacetime, the river offers release to Kinshasa’s claustrophobic expatriates. Roaring upstream in their motorboats, they picnic in the shimmering heat given off by the latest sandbank deposited by the current or scud across the waves on waterskis, weaving around the drifting islands of water hyacinth. Legend has it a European ambassador was once eaten by a crocodile while swimming and freshwater snakes are said to thrive. Yet far more ominous, for swimmers, is the steady pull of the river, the relentless tug of a vast mass of water powering relentlessly to the sea.

Some of this water has travelled nearly 3,000 miles and descended more than 5,000 feet. It has traced a huge arc curving up from eastern Zambia, heading straight north across the savannah as the Lualaba, veering west into the equatorial forest and taking in the Ubangi tributary before aiming for the Atlantic. The basin it drains rims Angola, Zambia, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Sudan, Central African Republic and Congo-Brazzaville. The catchment area straddles the equator, ensuring that some part is always in the midst of the rainy season. Hence the river’s steady flow, so strong that in theory it could cover the energy needs of central Africa and beyond. In practice, the hydroelectric dam built at Inga is working at a fraction of capacity – one of Mobutu’s many white elephant projects – and even domestic demand is not being met.

The local word for river is ‘nzadi’: a word misunderstood and mispronounced by Portuguese explorers charting the coastline in the fifteenth century. In rebaptising Belgian Congo ‘Zaire’ in 1971, Mobutu was acknowledging the extent to which that waterway, the most powerful in the world after the Amazon, defines his people’s identity. But what should have opened up the region has instead served to isolate it. On the map, the blue ribbon sweeping across the continent looks a promising access route. But the terrible rapids lying between the upper reaches of the Lualaba and Kisangani, Kinshasa and the sea, make nonsense of the atlas.

Looking west from the hotel, you can just glimpse the brown froth from the first of the series of falls that so appalled explorer Henry Morton Stanley when he glimpsed them in 1877. Determined to settle the dispute then raging in the West over the origins of the Nile, he had trekked across the continent from Zanzibar, losing nearly half his expedition to disease, cannibal attack and exhaustion. The calm of Malebo pool, fringed by sandy islands and a long row of white cliffs, had seemed a blessing to him and his young companion, Frank Pocock. ‘The grassy table-land above the cliffs appeared as green as a lawn, and so much reminded Frank of Kentish Downs that he exclaimed enthusiastically, “I feel we are nearing home”,’ wrote Stanley. In his enthusiasm Pocock, the only other white man to have survived this far into the journey, proposed naming the cliffs Dover, and the stretch of open water after Stanley. The reprieve proved shortlived. Three months later, still struggling to cross the Crystal Mountains separating the pool from the sea, Pocock went over one of the rapids and was drowned.

Leopoldville, the trading station Stanley set up here in honour of Leopold II, the Belgian King who sponsored his return to the area to ‘develop’ the region, was originally separate from Kinshasa, a second station established further upriver and dominated by baobab groves. The baobabs have gone now and the two stations have merged to form one inchoate city, a messy urban settlement of fits and starts that always seems about to peter away into the bush, only to sprawl that little bit further afield.

In the city’s infancy, the Belgian colonisers had laid out a model city of boulevards and avenues, sports grounds and parks. But with the population now nudging five million, all thought of town planning has been abandoned, the rules of drainage and gravity ignored. Nature takes its revenge during the rainy seasons, when mini Grand Canyons open up under roads and water-logged hillsides collapse, burying inhabitants in their shacks.

‘It looks as though it’s survived a war and is being rebuilt,’ a photographer friend, a veteran of Sarajevo, remarked after her first visit to Kinshasa. But the damage has been self-inflicted, in two rounds of looting so terrible they have become historical landmarks in people’s minds, so that events are labelled as being ‘avant le premier pillage’ or ‘après le deuxième pillage’, before and after the lootings. It is Congo’s version of BC and AD.

As for rebuilding, the impression given by the scaffolding and myriad work sites dotted around Kinshasa is misleading. The work has never been completed, the scaffolding will probably never be removed. Like the defunct street lamps lining Nairobi’s roads, the tower blocks of Freetown, the fading boardings across Africa which advertise trips to destinations no travel company today services, it recalls another era, when a continent believed its natural trajectory pointed up instead of down.

Down in the valley lies the Cité, the pullulating popular quarters. Matonge, Makala, Kintambo: districts of green-scummed waterways, street markets and rubbish piled so high the white egrets picking through it bob above the corrugated-iron roofs. In heavy rains the open drains overflow, turning roads into rivers of black mud that exhale the warm stink of sewage. On the heights, enjoying the cooler air, are districts like Mont-Fleuri, Ma Campagne and Binza, where spiked walls conceal the mansions that housed Mobutu’s elite and giant lizards in garish purple and orange do jerky press-ups by limpid blue swimming pools.

When the ‘mouvanciers’, as those belonging to Mobutu’s presidential movement were called, ventured downhill, it was usually to the Hotel Intercontinental that they headed in their Mercedes. It was a home away from home. They liked to sit in its Atrium café in their gold-rimmed sunglasses, doing shady deals with Lebanese diamond buyers, ordering cappuccinos and talking in ostentatiously loud voices over their mobile phones while armed bodyguards loitered in the background.

They were the only ones who could afford to patronise the designer-wear shops in the hotel’s arcade or hire the Junoesque whores – renowned as the most expensive in Kinshasa – who swanned along the corridors. They ran up accounts and left the management to chase payment by the government for years. Kongulu owed the casino a huge amount, but who could force a president’s son to pay?

It was never a place where those who opposed the regime could feel comfortable. Mobutu’s portrait stared out from above the main desk, his personality seemed to invest every echoing corridor. The Popular Movement for the Revolution (MPR), the party every Zairean at one stage was obliged to join, rented a set of rooms here and on at least one embarrassing occasion for management, a handcuffed prisoner was spotted in the lifts, being taken upstairs for interrogation.

Time the placing of your international call right and you could eavesdrop on the telephone conversations of guests down the hall, being monitored by the switchboard operators. The room cleaners showed a disproportionate level of interest in guests’ comings and goings. There was always a sense of being under surveillance. ‘We don’t hire them as such, but what can we do if the staff work as spies?’ a hotel executive once acknowledged, with a philosophical shrug of the shoulders.

By the mid-1990s the Intercontinental had, like the country itself, hit hard times. Zaire had become an international pariah and few VIPs visited Kinshasa any more. With occupancy below 20 per cent, service was stultifyingly slow. The blue dye came off the floor of the swimming pool, leaving bathers with the impression they had caught some horrible foot disease. The aroma of rotting carpet – blight of humid climates – tinged the air, the salade niçoise gave you the runs and the national power company would regularly plunge the hotel into penumbra because of unpaid bills. The first time I used the lift it shuttled repeatedly between ground floor and sixth, refusing to stop. ‘Yes, we heard you ringing the alarm bell,’ remarked the imperturbable receptionist when I finally won my freedom. After that I used the emergency stairs.

But there were considerations weighing against the growing tattiness, which accounted for the hotel’s small population of permanent residents. We were betting on the likelihood that if Kinshasa were to be engulfed in one of its periodic bouts of pillaging, the DSP would secure the hotel. They had done so twice before, in 1991 and 1993, when the mouvanciers had slept in the conference rooms, sheltered from a frenzied populace which was dismantling their factories, supermarkets and villas.

The hotel’s long-term guests were a strange bunch, representative in their way of the foreign community that washes up on African shores: misfits of the First World, sometimes intent on good works but more often escaping dubious pasts, in search of a quick killing, or simply seduced by the possibilities of misbehaviour without repercussions – that old colonial delight.

There was the ageing Belgian beauty, still sporting the miniskirts of a thirteen-year-old, who relentlessly sunbathed her way through every crisis, her appetite for ultraviolet seemingly insatiable. On the pool’s fringes hovered the skinny Chinese acupuncturist, whom everyone mistook for a cook because of his starched white hat. He had come to work on an aid project in Zaire which had never seen the light of day. Given the prevalence of HIV in Kinshasa, demand for acupuncture was minimal. But he had stayed on rather than return to communist China. ‘Here, it is bad. But in China, I think, maybe worse,’ he confessed.

On first name terms with most of the mouvanciers was the blond, big-hearted American with a southern drawl who slopped around in flip-flops and T-shirts. Just what he was doing in Kinshasa was a mystery, but he would often use a vague, collective ‘we’ when referring to those in power. The Zairean staff referred to him openly as ‘the CIA man’, although the American embassy claimed to be unaware of his existence. Somehow, one couldn’t help feeling that a real CIA man would have been a bit put out at having his role so universally recognised.

There were bored foreign pilots who flew supplies into UNITA-held territory in Angola, busting UN sanctions on salaries generous enough to merit turning a few blind eyes. ‘I have told my bosses, the one thing I will never do is fly arms,’ said Jean-Marie, a charming Frenchman. ‘They can ask me to do anything else, but not that.’ I would nod sympathetically, pretending to believe him.

Jean-Marie looked great in his pilot’s uniform and spent a lot of time gently chatting up aid workers around the pool. He had shown me a photograph of his girlfriend back in France, who looked stunningly attractive but was clearly half his age. A Saint-Exupéry gone astray, he would return from trips halfway across the world – not carrying arms – and rave with Gallic lyricism about the beauty of the night sky from the pilot’s cockpit. When he fell out with his bosses, he moved into a house the CIA man had started renting, although he said the mysterious goings-on there made him uneasy. One day he disappeared, never to be heard of again, and with him went the several thousand dollars it emerged he had borrowed from the CIA man and his aid-worker girlfriends.

And finally, of course, there was the pony-tailed piano player. Wizened and impassive, he had been playing in the Atrium café as long as anyone could remember. He had tinkled out his lugubrious version of ‘As Time Goes By’ as his frame became more hunched and his hair turned from black, to first salt-and-pepper, and finally to dirty white. By May 1997, it was the piano player’s puzzling absence, as much as any other event, that signalled a fundamental change was looming. A seismic shift in the world as we knew it was about to take place, and the piano player, for one, did not want to be around to see it.

The rebel movement born in Kivu in late 1996, which had triggered hoots of derisive laughter when it had pledged to overturn Mobutu, had proved far more formidable than anticipated. As it had begun capturing territory, sceptical Zaireans had gone from dismissing it as a Rwandan invasion led by a discredited Maoist to welcoming it as a liberation force. Neighbouring countries with long-standing gripes against Mobutu joined the bandwagon and the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL) picked up momentum.

Up in Binza, the mouvanciers had gone from haughty dismissals of the rebel problem to frantic questions: why wouldn’t Mobutu DO something? Drained by prostate cancer, the president had curled up in his lair on the hill like a sick animal. ‘When you are a soldier,’ he declared, ‘either you surrender or you are killed. But you don’t flee.’

Days dragged into weeks. Bracing for the worst, anxious Western governments quietly pulled together a force in Brazzaville whose commandos practised the cross-river trip in high-power motor-launches and helicopters. The diplomats were busy, juggling a stream of visa requests from the mouvanciers with preparations for the evacuation of expatriates who were stubbornly refusing to heed the increasingly forceful warnings issued over the BBC World Service.

‘We’ve built a special cement step to allow women with high heels to get into the motor launches. And I’ve even got peanuts and chocolate bars ready for anyone who might starve to death while we’re waiting for our men,’ an ambassador proudly announced. He had gone on a trial run across the river and returned somewhat breathless. ‘Door to door, it took just three and a half minutes.’

The rebels kept marching. National television broadcast footage of General Nzimbi Nzale, head of the DSP, haranguing his troops for hour after hour, ordering them to defend Mobutu to the death. The camera frame was tight and one assumed, from his hoarse tones, that he was addressing an audience of thousands. But the military made the mistake of allowing a foreign television crew to attend the same event. They filmed the general from behind, revealing a couple of dozen nose-picking soldiers, vacant-eyed, barely paying attention. Could these be the same men who had drawn up a list of strategic sites to be blown up and personalities to be assassinated once the rebels reached the city, a list leaked to Kinshasa newspapers?

In the Hotel Intercontinental the shops, anticipating the looting that traditionally preceded the rebels’ arrival, first slashed the prices on their designer brands and then staged ‘everything must go’ sales, trying to shift stock before a more dramatic type of ‘liquidation to tale’ occurred.

But their usual customers were no longer interested. Quietly, the mouvanciers were abandoning their villas in the hills and moving down to the Hotel Intercontinental, where they spent fitful nights, armed bodyguards perched on seats outside their rooms. You would spot them in the lobby, surrounded by matched sets of Louis Vuitton luggage, before they boarded planes and headed for properties bought years before in Belgium, France, Switzerland and South Africa in preparation for just such a day. It was almost possible to squeeze out a tiny pang of sympathy for these, the most well-heeled refugees in the world.

As for the expatriates, they had been told by their embassies to keep one holdall at the ready for the eventual evacuation, so shopping was ruled out. The designer stock stayed stubbornly put, and the evening ritual amongst journalists staying at the hotel became a window-shopping tour to mentally select which bargain to snatch as the crowds surged through the plate glass.

‘What you have to realise is you’ll only get the chance to go for one item,’ a veteran correspondent told me with deadly seriousness. ‘There won’t be any time for faffing around. So it’s all about focus. Quick in, quick out.’ I dallied for a while over a pair of yellow lace knickers with matching bra. But in the end a tan leather jacket, worth at least $1,000, I reckoned, by Kinshasa prices, won my vote.

We were not the only ones getting light-headed with anxiety. A dinner hosted by a Zairean friend who worked at one of the ministries was a jolly, noisy meal until one of the guests called for silence. Looking around the gathering of lawyers, university professors and consultants, he raised a glass of pink champagne and reminded them that this was exactly the social class targeted for elimination after Liberia’s 1980 army coup. ‘Let us drink a toast to change, and pray we are all still here in a year’s time to celebrate,’ he said.

Soon after, a curfew was announced, and evening outings came to an end. Defeated soldiers and deserters were trickling into Kinshasa, hijacking the first cars they stumbled upon. It was no longer safe to venture out after dark. Instead, along with a growing number of crop-haired ‘security experts’ brought in by the embassies, we were confined to the Intercontinental’s pizzeria, where the band laughably dubbed ‘Le Best’ serenaded us with a muzak medley which always featured a particularly mournful cover version of ‘Hotel California’. ‘You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave,’ they wailed.

All airlines had now cancelled their flights to Kinshasa and the ferries had been requisitioned by the government. After weeks spent wondering whether to go or stay, the decision had been taken out of our hands.

The Hotel Intercontinental manager was finding the experience as claustrophobic as the rest of us. His appearance was as natty as ever, but his face was beginning to show the strain. ‘How much longer is this going to go on? I can’t eat, I can’t sleep. It’s giving me ulcers,’ he confessed over breakfast. Fearing a siege, he had stockpiled enough food, water and diesel to cater for 2,000 people for at least a fortnight. Now he chose to combat the tension the only way he knew how: by entertaining in style. Select, candle-lit dinners were staged in the wine cellars of the hotel. Surrounded by dusty vintages, nestling in the bowels of the building, for one brief night we felt sheltered from the approaching storm.

‘Do you really think these Tutsi troops are going to be as effective as people say?’ asked my neighbour as we savoured the nouvelle cuisine. ‘I suspect it’s all a myth. It’s easy enough beating the Zairean army out in the sticks. But surely when the rebels get to Kinshasa, and the DSP have nowhere left to run, it’ll be completely different?’

It was a view I heard repeatedly, but not one I shared. I had no expectations the DSP would ever do battle. What I feared was that they would go for the soft targets, like journalists. I had developed a habit of shouting in my sleep and regretted now checking into the sixteenth floor. A precise image haunted me: looking through the spyhole in my door and seeing two DSP men, guns cocked, about to break into the room and toss me out of the window. Even if I hit the main building on the trip down, there was no way I could survive the fall from that height.

Radio Trottoir, ‘pavement radio’, as the city’s gossip network was known, was in overdrive. There were rumours of Chinese mercenaries landing in their hundreds, of Zulu troops being called in from South Africa, of goose-stepping soldiers coming in from North Korea to save Mobutu. Also circulating were leaflets telling residents who wanted change to tie white bandanas around their foreheads when the rebels arrived as a sign of support. On the main routes into town, tanks and artillery had been set up. But with each soldier convinced a rival unit was bent on treachery, they were too busy watching each other to stop the steady flow of infiltrators into Kinshasa.

Given the steady ratcheting of tension, it was no surprise that on 15 May anyone who owned a television sat glued to their set. Since mid-afternoon a message had been running across the screen, promising an important press conference. The word on Radio Trottoir was that Mobutu had been meeting with his generals and his departure was about to be announced.

The hours ticked by and nothing happened. The message continued to unroll. Finally, after midnight, a nervous newscaster appeared. To a rapt audience he read out a bland summary of the day’s events, rounded off with a piece of homely advice: viewers should watch out for the small beetles emerging after the recent seasonal rains, which packed a particularly nasty bite.

Whatever talks had taken place in Zaire’s upper echelons, commonsense had not triumphed. Mobutu, who had always warned his countrymen that ‘ma tête vaut cher’ (‘my head won’t come cheap’) could not let go. When he drove to the airport the following day, heading for the jungle palace where, it was said, he planned to exhume his ancestor’s bodies to save them from desecration by the rebels, he stole away in silence, having taken none of the hard decisions demanded.

And so it was that six hours after the death squad’s first unwelcome visit to the Intercontinental, I found myself peering over the balcony, watching as the parking lot below filled with gleaming jeeps and flashy sports cars. Kongulu and his men were back, and this time they had arrived in force.

The lifts filled with panicking women, their hair in a mess, juggling sleepy children in pyjamas, bulging holdalls and plastic bags full of documents. Not only had we been sleeping alongside the regime’s fifth columnists for the last few days, it emerged, we’d been unwitting neighbours of the DSP chiefs’ extended families.

I could see their menfolk patrolling nervously up and down, toting sub-machine guns and draped in cartridge belts. They were wearing their trademark sunglasses, those gold-rimmed feminine accessories which should look comic on a man but instead manage to look as sinister as the wedding dresses and blonde wigs worn by Liberia’s drugged fighters. They are the modern equivalent of the wooden masks donned around night fires by warriors preparing to do battle, which turn their wearers into something utterly alien – faceless instruments of violence capable of unspeakable acts.

We had chosen the Intercontinental because of its track record of safety. But in a shifting world order, yesterday’s guardians could turn into today’s hostage-takers. Looming all too vividly now was the possibility that the DSP might choose to make its last stand at Mobutu’s hotel. Did our nosy room cleaner and nervous taxi driver, neither of whom had made an appearance that day, know something we didn’t?

I called the British head of a security company downtown. ‘Just let us know if you get too concerned and we’ll come and get you,’ he said breezily, as though it was the easiest thing in the world. But word came that a camera crew trying to leave the hotel had been roughed up by the DSP and turned back. Summoning assistance might simply precipitate a crisis. More hopeful news came from journalists trapped at the Hotel Memling, that other de facto media headquarters in the centre of town. Closer to the action, they were watching retreating Zairean soldiers streaming along the boulevards, a retreat turning into a rout. As they surrendered ground, the men were removing their uniforms to emerge as harmless civilians.

Down in the lobby, a similar remarkable metamorphosis had taken place, almost without our noticing. Uniforms and weapons had all disappeared. Scores of muscular young men were lounging about in modish tracksuits, not a hint of camouflage or khaki in sight. The Hotel Intercontinental suddenly appeared to be hosting a well-attended sports convention.

The truth dawned: the Intercontinental was not going to be the stage for a new Alamo. The DSP had laid their plans in advance and were using the hotel as a way station where they could round up their families and change into civilian clothing before heading for the river. From cursing the inaction of the Western force in Brazzaville, we went to praying they would keep away. The last thing we needed now was for the DSP’s exit to be blocked.

Indeed, the DSP were encountering something of a logistical problem, as the first to flee had left their boats on the wrong side of the river. And this was when the Hotel Intercontinental suddenly justified its outrageously inflated prices, making up for all the suspect salads and blue feet, the years of skittering cockroaches and terrible muzak. From his office, our hotel manager called up his Lebanese friends and explained the situation. Swiftly a small fleet of Lebanese-owned motor-launches was assembled to ferry the new-found sports enthusiasts and their families across to Congo-Brazzaville. One convoy after another headed out, the limping wounded bringing up the rear. The hotel miraculously emptied and we heaved a sigh of relief. A showdown that could have cost hundreds of lives had been averted.

Across the deserted city, the Western security experts were at their work. On one street corner, a Belgian sharp-shooter took careful aim as a colleague ushered out a group of terrified nuns. Roaring around Kinshasa in a UN jeep, another leathery veteran had set himself the task of persuading what few soldiers remained to disarm. In the patronising tones you might use with a naughty toddler, he was telling teenagers so drunk they could barely focus to drop their rocket-grenade launchers before they did themselves a mischief.

By the river’s edge lay what remained of Kongulu’s sports car. Abandoned when he boarded a speed boat, it had already been stripped by looters of tyres, seats and spare parts. Along the same waterfront, Prime Minister Likulia Bolongo had also made his escape, ushered by French commandos onto a helicopter. Driving past the Hotel Memling, we noticed a dozen camera tripods laid out in a surreally neat row. The Japanese journalists, it seemed, had decided that the rebels would oblige them with a historic photo opportunity by marching down Kinshasa’s main boulevard. In fact they were being a little more unpredictable, fanning through the surrounding districts. We finally stumbled upon them near the sports stadium: a group of quiet, disciplined Tutsi youths allowing themselves to be appraised by a curious crowd while they rested near a shot-out BMW. Its DSP passengers had abandoned their uniforms, but the strategy had not saved them. Riddled with bullets, they lay face-down in pools of blood.

Back at the Intercontinental, the Belgian sun-worshipper was already in her bikini, catching up on missed rays. But the hotel’s official liberation did not come until the following day. Leaving the breakfast table, I had gone to see whether our taxi drivers had returned to their normal spot under the trees. And suddenly, there the rebels were. In flip-flops and bare feet, most of them no more than boys, staggering under the weight of shells and pieces of equipment, the column of AFDL fighters stretched as far as the eye could see down the Avenue des Trois Z.

Housewives ran in their dressing gowns across the lawns, brandishing cartons of Kellogg’s Cornflakes and Cocopops as placatory offerings. But the adult commanders kept chivvying the exhausted ‘kadogos’ (little ones) along, afraid they would fall asleep as soon as they stopped moving. ‘You must be tired,’ sympathised an onlooker. ‘Yes. I’ve walked all the way from Kampala,’ replied one boy, artlessly spilling the beans on Uganda’s involvement in the rebel uprising. ‘Sshhh,’ remonstrated his superior.

Abandoning their coffees, the hotel guests emerged to watch. There was a smattering of excited applause as the khaki procession wove its weary way up the hill to Binza, home of the mouvanciers and the site of Camp Tsha Tshi, Mobutu’s last bolt-hole. From start to finish, the capture of a city of five million people, climax of the rebel campaign, had taken less than twenty-four hours. For the first time in history, a group of African nations had banded together to rid the region of a despot. The event was hailed as the start of an African Renaissance, spearheaded by a ‘new breed’ of African leader.

Over the next few days, Kinshasa made the changes appropriate to its new role as capital of the rebaptised Democratic Republic of Congo. The word ‘Zaire’ was removed from public buildings and road signs, leopard statues were blown up and the national flag – the flaming torch of the Mobutu era – painted over with the AFDL’s blue and yellow. To jog rusty memories, newspapers printed the words to ‘Debout Congolais’ (‘Congolese Arise’), the post-independence anthem being revived by Laurent Kabila, who traced his political lineage back to Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first prime minister.

With ironic inevitability, the rebel leader who had promised to retire from the fray once Mobutu was toppled declared himself president and moved his administration into the Hotel Intercontinental. One day there was a peremptory knock at the door while I was in the shower. Looking through the spy hole I finally saw my nightmare vision made flesh: two twitchy young soldiers, rifles at the ready. But it was only the AFDL, checking for weapons, not a DSP unit intent on my defenestration.

In the hotel corridors, where the shops swiftly removed their ‘sale’ signs and jacked their prices back up, a new generation of lobbyists milled in search of advancement. The Atrium echoed with English and Swahili, instead of French and Lingala, and in the restaurants ragged AFDL fighters replaced the sinister DSP. But they shared their predecessors’ habit of never paying. The manager’s face grew taut once more. He was not amused when one of the rebels caused a bit of a ruckus at breakfast one day, carelessly dropping a grenade which rolled under the selection of almond croissants and pains au chocolat.

In theory, the AFDL was now in charge of one of Africa’s richest states, a country blessed with diamonds and gold, copper and uranium, oil and timber. In practice, it had inherited a country reverting to the Iron Age society first encountered by the Portuguese explorers of the fifteenth century. The infrastructure was shattered, the army hopelessly divided. The state boasted more than half a million civil servants, who did little but wanted compensation for months of salary arrears. Foreign debts had accrued to the tune of $14 billion; the country had disastrous relations with all international institutions of importance and, worst of all, a population cynically inured to breaking the law.

With a simplistic rigour that could only be explained by the decades its cadres had spent outside the country, the AFDL set about the task of moral spring-cleaning. There were to be no Liberia-style executions. Instead, the new government declared the independence of the central bank, the institution Mobutu had treated as his personal cash reserve, and sacked the heads of the state enterprises Mobutu had milked for revenue. They went to join the former ministers and presidential business associates awaiting trial in Kinshasa’s infamous Makala jail, specially repainted for its VIP intake.

Top of the investigators’ list, of course, was Mobutu himself. The rebels had started legal proceedings well before reaching Kinshasa, firing off requests for the president’s assets to be frozen in a dozen European and African countries while still on the move. Claiming he had evidence that Mobutu had appropriated a staggering $14 billion, with $8 billion of that stored in Switzerland alone, incoming Justice Minister Celestin Lwangi pledged to reverse the flight of capital.

But as the vestiges of Mobutu’s reign were painted over and the Hotel Intercontinental, symbol of his rule, appropriated, the departed dinosaur did manage to exact his petty revenge. One of the last actions performed by the DSP families before heading out was to rid themselves of their Mobutu mementoes, stuffing MPR T-shirts and cloth printed with the president’s face down the hotel lavatories. For the first week of the new regime, the AFDL leaders had to go outside to relieve themselves. Mobutu was literally clogging up the system.