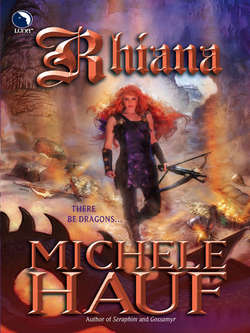

Читать книгу Rhiana - Michele Hauf - Страница 8

CHAPTER FOUR

ОглавлениеWhat manner of soul did she possess?

That she had physical differences from others could not be dismissed. So she had red hair and freckles. Ignorance caused others to tease her. The color of one’s hair did not make them evil or unclean. There were many in the village with red hair. Of course, it was not so bold as Rhiana’s, as if sun-drenched garnets. And she could not disregard her unusual eyes. Only those who really looked at her noticed. She did not call attention to the fact one eye was gold, the other green. Lydia’s eyes were green. But when Rhiana asked, Lydia would not verify if her father’s eyes had been gold.

At the end of a stretch of houses, in the row facing the gardens, stood the chapel. Entering the always open doors, Rhiana genuflected toward the front of the church, then straightened and dipped her fingers into the fount of consecrated water. There was no permanent priest, but the one who traveled along the coast was currently in residence at the castle for a fortnight.

Tracing a cross over her forehead, she whispered a Hail Mary. Confession must be made soon; it would erase her venial sins, but not the mortal ones. So she did not sin mortally.

Or so she hoped.

Could slaying dragons be considered a mortal sin? She did not know if, by taking the life of a dragon purposefully, she robbed their souls of divine grace. God had cursed them. What grace could they have? Did they even possess a soul?

There were a few benches near the door. Most ladies brought along their own simple velvet-cushioned prie dieu to place in the nave. Rhiana liked the open space. No clutter, no sign of the riches upon which the village thrived. Just simple peace.

Striding to the front of the small church, she knelt upon the stone floor and pressed her hands together.

A wooden cross hung over the altar, supported by ropes on either arm of the cross. Carved from limewood and not oiled, the wood bore a few holes from burrowing insects, but that only gave it more charm, Rhiana mused. It was far from the grandiose cross embellished with rubies and gold that she had seen in the castle chapel. She did not care to worship a gaudy master.

Lord Guiscard’s penchant for finery oftentimes made her wonder if Lady Anne were not just another bauble in his collection. For truly, it was as if he had plucked her out from a treasure box. With no family to name, and no origins to claim, the woman had arrived in St. Rénan three years earlier, already wed to the baron. (Yet, for all purposes, she had claimed the grasshopper as her family sigil.) Barely seventeen at the time, Anne had spoken little, yet her round dark eyes had seen all.

She had reached out to Rhiana one eve during a hoard-raid fête, drawing her close into a hug.

“So pretty,” Anne had said of Rhiana’s hair. “Like fire. I like fire.”

That was all Rhiana had needed to hear to comply should Anne ever request her presence.

Though she was hardly an orphan, Rhiana felt an affinity to Anne. They were two alike, in a manner she could not quite decide. While Anne’s mind was not always her own, and she often flighted from reality, Rhiana could sense the young woman’s distinct need for belonging. To understand.

For Rhiana longed to understand.

“What am I?” she whispered now to the cross. “Why do I…?”

Not burn.

The preternatural trait must always be hidden from others. Rhiana would not speak of it, except to Paul, and only then when they were assured no others were close to hear.

Upon her sixteenth birthday Rhiana had forced herself to visit the Nose. The old woman had earned her name because she was always nosing about, had her nose into everything, and knew more than most even knew about themselves. The Nose moved in the shadows, held stealth in her breast, and yet, was no more threatening than the elder widow she was. She was not a witch, though mayhap a sage of sorts. Empyromancy is what she practiced, reading the future in the flames of a hearth fire or the wild ravages of a bonfire. The Nose lived at the south edge of the village, apart from all the rest, not caring to participate in the hoard-raid festivities, but quietly accepting her portion of the yearly stipend and pocketing it in the rags she chose to wear. Her participation in St. Rénan’s way of life was the fertilizer she created to cover the castle gardens that produced some stunningly large vegetables and abundant medicinal herbs.

After staring at Rhiana from across a table covered in moth-eaten cor-du-roi, squinting and sniffing as if determining her species, the Nose shot upright and declared her not a witch, but something so much more. Pressing a palm before Rhiana’s face, her withered fingers had moved like spider limbs testing the air, and then retracted as if stung by a bee in her web. With a shrill cry, she’d hastened Rhiana from her home and admonished her never to return.

Not a witch.

Something so much more?

But what then?

Touching the moist line of the cross she had traced onto her forehead, Rhiana now mused that it matched the kill spot on a dragon’s skull. Put there to remind the beast of what it could never have—divine grace.

Legend told of fireless dragons that long ago roamed the earth. Then the dark angels fell. And the dragons, enticed by the wicked creatures that had defied their God, had mated with them. In punishment, He had reached down from the heavens and touched the dragons’ foreheads. Their first offspring had been born breathing fire, a gift from the angels of hell—Lucifer’s breath—and an inverted cross upon its brow, the kill spot, a punishment from heaven.

Had she been put into this world specifically to slay dragons? It felt right. When she stood before a fiery beast and defied it with her crossbow and sheer mettle Rhiana felt in her element.

Why Guiscard insisted she not continue, she could only guess was because she was female. Surely, if a male dragon slayer offered to defeat the nest of beasts, the baron would agree to the offer?

“Would he?”

She’d not gotten that feeling from him. For some reason, Rhiana sensed Lord Guiscard would do nothing to stop the imminent threat to St. Rénan. And that feeling unsettled her.

Shuffling to sit on her haunches and spreading her legs out before her, Rhiana rested her elbows on her knees. Hardly a ladylike position, especially with the gown rucked to her calves, but she was alone.

There was some part of Narcisse Guiscard that Rhiana understood on a deep inner level. Gentle and patient, he cared for Lady Anne like no other. That he had even accepted a woman not always of her mind into his life spoke untold compassion.

And yet, each time Lord Guiscard looked at Rhiana she felt his desire crawl across her flesh as if a seeking insect. A duplicitous man. And while that very look was exactly the kind of regard Rhiana craved, she would not answer its plea.

“Never,” she whispered. Not from a married man. Not from any of the knights in the village who had pledged to Guiscard. They were all so brutish. The sort of man Rhiana desired must understand a woman, above and beyond her eccentricities. He must not be a brute. Yet, he must practice chivalry. An equal? It was too much to hope for.

Bowing her head she summarized a silent prayer. Thanks be for her strength and skills. Please to keep her family safe and all others in the village she loved and cared for. Paul and Odette. Her mother. Rudolph. Anne. Yes, even Guiscard, for he did love Anne.

And send understanding. Knowledge. Or mayhap, merely acceptance for the unknown.

Crossing herself from forehead to stomach and shoulder to shoulder, Rhiana then stood and glanced out the narrow stained-glass window to her left. The village actually echoed with voices. A good thing to hear after days of silent terror.

On the other hand, if the villagers became complacent only ill could come of their fall from vigilance.

Sweeping up her skirts, Rhiana strode toward the back of the chapel, but noted a glint of steel lying on the floor below the final bench. A leather-sheathed broadsword. The hilt was wrapped in scuffed black leather. Must belong to one of Guiscard’s knights, ever hopeful for a skirmish.

Rhiana drew it halfway from the sheath. The blade held more than a few dings and scuffs. A well-used weapon. Hmm, then it could not belong to any in the garrison. There had been a time when the garrison fought to protect the city from marauders and sea pirates. But the port had closed decades ago, and now the city rarely saw travelers of any sort.

Though it did not bear his mark on the pommel, Paul would know to whom this sword belonged. A small flared rooster crest be his mark, taken from his great-grandfather’s coat of arms. ’Twas Paul Tassot’s proof mark, a sign the armor he’d made had been tested by arrows and was impenetrable at a distance of twenty paces.

Sword in hand, Rhiana set out for the armory. The noon sky brightened her mood. A flash of brilliant white glanced off the bronze roof topping the bath house. Not a single cloud this day. The only thing that could make the day better would be a bit of rain to drench the crops on the south side of the curtain walls.

“I’ve killed it!”

That declaration sounded too ominous to be a good thing. Rhiana dashed for the bailey where a small crowd had gathered. They surrounded something that moved and struggled about on the dirt courtyard. Was it a fallen horse? She could but see a flailing dark limb.

“Stomp its head!”

“Have you another arrow?” someone cried. “Get me a dagger!”

Rhiana pushed between two teenage boys and spied what had caused the commotion. A shout burst from her mouth before she could even summon sense. “Back! All of you! What have you…”

Plunging to her knees, she splayed out her palms before the struggling beast. Gawky and thin, it resembled a gargoyle nesting the castle tower come to life. It had taken an arrow in the pellicle fabric of one of its supple black wings.

“Rhiana?” Paul’s voice, as he pushed through the crowd. “What is it? Oh…”

“It is a newling,” Rhiana said to all, hoping an explanation would cool their lust for its life. “A baby dragon.” The crowd gasped in utter horror. “It will harm no one. Why, it is no larger than a dog. Who shot it?”

Protests against self-protection and thinking it was a big bird shuffled out in nervous mutters.

“It is a dragon!” Christophe de Ver snapped. He’d sought to join the garrison, but his awful eyesight kept him from earning his spurs, and resulted in more than a few tumbles and visits to Odette for stitching. “You killed one this very morn, my lady. Why are you so keen to keep this one alive?”

So word of her kill this morning had already breached the masses? Couldn’t have been Guiscard’s doing.

“It is but a babe,” she said. “Can you not see it is helpless? Was it you who shot it?”

Christophe nodded proudly. Rhiana must, for once, be thankful that the man’s myopia had altered his aim.

The newling mewled. It struggled to sit its hind legs. Its wounded wing shivered and stretched. It was completely black, the scales shimmery, yet supple. Easily pierced with an arrow.

“Bring it to the armory,” she heard Paul say. “We mustn’t keep it overlong.”

“We must kill it!”

“No!” Rhiana stood and bent over the newling. “We will remove the arrow and tend its wound. Then we must release it, or its mother will come looking for it.”

“Its mother?” Someone spat. “There are more dragons?”

“She will come anon!”

“And whose fault is that?” She could not argue with the idiocy of these people. And their cruelty. To bring down one so small? “Paul, can you lift it?”

Her stepfather knelt before the newling, and sweeping his arms around the thing, managed to cradle it into his embrace. Vision blocked by the spread of a good wing, Paul hoofed it quickly to his shop. Mewls scratched the sky, and the circle of villagers followed their steps to the armory. Rhiana closed the door on the curious faces and followed Paul into the warmth of the shop.

He set the newling on the wood floor before the brazier where solid ingots of iron waited his coaxing. “It may like the heat,” he suggested, and stepped back to stand beside Rhiana. The twosome shook their heads as the creature stood, and then stretched out its good wing. It squeaked loudly as its attempts to stretch the wounded wing resulted in it wobbling and stumbling to land on its tail. Then, with wide black eyes that seemed to beg for tenderness, it scanned its surroundings.

“This is not good.”

The newling rubbed its hind legs together. The horny projections on the backs of its legs created a piercing stridulation.

“Immensely not good,” Rhiana agreed. “Let’s get the arrow from its wing and send it on its way. That sound it makes… I think it is calling for its mother.”

Rhiana tried to hold it carefully without embracing overmuch, or making it feel captured, while Paul cut the wooden arrow with a clipper and carefully drew it from the wing.

The newling continued to stridulate. And Rhiana kept a keen eye to the open window. She looked beyond the horrified stares of the villagers and to the sky. Clear. For now.

“There.” Paul stood back, holding the two pieces of arrow. “Set it free.”

“Should we not cauterize the wound? It could become infected.”

“Rhiana, I want that thing out of here.”

“Very well, but what if it cannot fly?”

The newling stretched out its wing and shrieked.

“Then it can walk home. Take it to the parapet and release it. Or shall I do it?”

“No,” she said. “I can.”

The newling dropped to the ground like a rock.

Leaning out over the crenel between two merlons, Rhiana cried out. She should not have expected the small dragon to be able to fly with a hole in its wing. Yet, it wobbled off, away from the battlements, stridulating occasionally.

“Be quiet,” she said, but knew the hope was fruitless. “I should have carried you home. Oh, what—”

A cloud soared overhead, streaking the parapet Rhiana stood upon in a fast-moving shadow. Much too quick for rain—

Tensing at the shiver shimmying up the back of her neck, Rhiana did give no more time to wonder at the weather. ’Twas no cloud. Nothing could move so swiftly. Save, a dragon. And not a small, wounded newling, but mayhap…its mother.