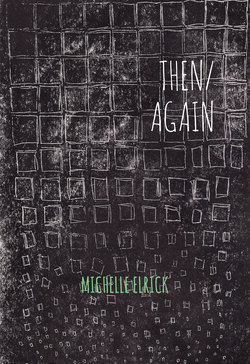

Читать книгу then/again - Michelle Elrick - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

“Space transforms into place as it acquires definition and meaning.”

—Yi-Fu Tuan, Space and Place

“The imagination of going home so frequently means going ‘back’ in both space and time. Back to the old familiar things, to the way things used to be. … [T]he truth is that you can never simply ‘go back,’ to home or to anywhere else. When you get ‘there’ the place will have moved on just as you yourself will have changed.”

—Doreen Massey, For Space

It is the height of spring. Winnipeg’s annual thaw is soaking the soil, filling rivers to the brim. Silt water floods the lowlands depositing new, fertile mud. Wet clouds ride warm air, raining fresh water from the sky. And as the sun reaches through the atmosphere to touch my bare skin, my body remembers. Hot August, the relief of shade, the sweet scent of sunbaked skin. Today I’m leaving on a journey to find the homes of my past. Only one of the places I’ll visit was a former residence of mine; the others are homes I have inherited through ancestry. I’ll be visiting the Parish of Rathven, Scotland, where the last Scottish Elricks of my paternal line lived prior to their emigration in the mid-nineteenth century. Then I’ll be in Salzburg, Austria where my mother was born and raised until age ten, with a final stop in Abbotsford, British Columbia where I spent my first twenty years.

What is home? Since childhood, I have played with various definitions, trying to get at the heart of the concept, to pin it down with meaning. At its most basic, home is a place to be from, a current address or childhood residence. Then again, home can also be as nondescript as a region on a map or a suburb vibe or a downtown feel. Almost immediately, the definition gets complicated. I have come back again and again to the axiom “home is where the heart is,” which my mother had hanging in cross-stitch on the kitchen wall of the Monashee house where I learned to read. This definition includes people—the people I care about and remain intimately connected to despite place or proximity.

I moved many times in my twenties—often within the same city, yet I also tried new cities, averaging one move every eight months over my first ten years on my own. During this time, I kept certain cardboard boxes that had proved their functionality and showed no signs of bottoming out. I became a master of the homey, able to move in, unpack, set up and host a dinner party within the first two days of getting the keys. With all the packing and unpacking, I began to think of home as “what you take with you when you go.” While all of these definitions describe home in a limited way, none show the many facets of how we use and understand the word “home.” I’m left to understand home as a felt and sensed thing, not limited to place, people and context, but including personal and collective histories, myth and family legend, as well as texture, flavour and a repertoire of sensual experience that produces feelings of familiarity and comfort. At the centre, this is a story of encounter.

Rathven, Late May

The North Sea glitters green in the sunlight, smoke-blue in cloud shade. Gulls perch on the wind over rocks that break the tide. Kelp and shellfish darken the shore, pools of tidal life drown and surface twice daily with the ocean’s wet breathing. At my back, the harbour village of Buckpool, Scotland hunkers shoulder to the wind at the base of the cliff that once delineated fishing folk from farming folk. Above the cliff edge is Buckie proper, a metropolis in the remote and rural sense of the word. Two kilometres southwest, a footpath leads along the burn to the village of Rathven. With little more than three roads and two short dead-ends, Rathven is easy to overlook; it was once considered the centre of the region, the root of the parish, the home of the school and the cemetery. It is also where the Elricks lived—James, Ellen and their five sons—before they made their gradual migration to Canada in the mid-nineteenth century.

I was here almost a year ago today looking for Alexander Elrick, the last Elrick of my lineage to die in Scotland. Alexander’s twin brother James emigrated first, followed by the rest of the family. There are no records in our family history of what became of Alexander, whether he fathered a branch of great-aunts and uncles, cousins and second cousins, or whether this part of the family tree died out. The first five days of my search brought me through the library’s microfiche records, the local museum and several cemeteries, yet I had no luck. If only I could find him, I told myself, his descendants or even his bones, I’ll have found the title to my Scottish ancestry, however remote or reduced by the generations between. On the last day of my stay, I took shelter from the heat of the afternoon sun in the shade cast by a simple granite headstone, marking the bones of Alexander, his wife and children, the end of that Elrick line.

Buckpool is different this time. Even though I’m staying at the same cottage with the same furniture and the same view, it is not the same. I have changed. Time has passed and I see here differently, feel it differently. The stories I’ve inherited (such as the Elrick emigration) and others I’ve told myself only speak about place, not through it, and they speak from a rear-view perspective that reads the ripples in the pond in a way that warps the shape of the stone. This place, like all places, resides in the moment of my encounter with it, particular and fleeting. Alexander’s bones may offer an inheritance of Scottish soil, yet for an inherited place to become a home of mine, rights are inconsequential. Home remains a concept apprehended by the body.

Salzburg, Early June

I wander through the labyrinthine streets of Salzburg following an eight-year-old memory. Wandering, yes, as I reestablish my bearings, yet I have a destination in mind: a particular beer garden surrounded on all sides by centuries-old apartments, home to a walnut tree that extends a generous canopy across dozens of café tables where rock-salted pretzels sit and cold beers sweat in the heat of the afternoon. I remember this place as the point from which I departed eight years ago for a solitary hour and a half, leaving Opa behind under the walnut tree while I shopped, grateful for a bit of time alone. We were in the middle of a holiday in Salzburg and Budapest. Opa was showing me where he came from.

At the upper exit of the tunnel, turn left. This is all I remember about the relationship between the boutiques and the walnut tree in the courtyard. As I weave through archways and cobbled streets diagonally, my memory tells me I need to make my way partly around the Mönchsberg, closer to Mozart’s house and toward the barbershop where Auntie Elfie worked as a young woman. From there, the beer garden shouldn’t be hard to find.

Partway through the old city, I come to a familiar place: a giant fountain, statues of horses. The museum rises cool and modern amid Salzburg’s gothic churches and baroque apartments. I enter to get my historical bearings: Where am I? becomes When am I? Floor by floor, I browse the exhibits until I come to a small room where a timeline wraps the walls like a ribbon, folds and coils through the centre, and ends with today. I read. The history of the place deposits me here, just before noon, where I am beginning to feel thirsty. On my way out I visit the gift shop. There is a six-foot-long poster on display, a reproduction of Johann Michael Sattler’s oil panorama of the city, which he painted between 1826–1829 from drawings he made atop the Hohensalzburg Castle. Close inspection reveals the city clocks and sundials all show four o’clock. I decide to buy it. Not the most practical map, but still remarkably accurate. The panorama tells me where I am, but until the clock strikes four, it says nothing of when.

Getreidegasse clutters as tourists begin their daily shopping. I walk up its gentle slope, toward the dead-end breast of the mountain. Somewhere ahead was Auntie Elfie’s barbershop. I pass the boutiques and find the tunnel, pass through the arched channel and arrive at the walnut tree. It alone remains of all that was here last time. The courtyard is curtained off with scaffolding and plywood fences. The beer garden has become a construction zone and the earth is missing its skin. Walking partway around, I peek through a vertical crack. There isn’t a pretzel in sight. I walk back to the top of the tunnel. Turn left into a stream of people, flowing both directions.

Abbotsford, mid-July

Sound travels up from the foot of the mountain to the rock-terraced garden below the balcony where I sit. A young doe and buck paw cool, red beds in the cedar mulch, then kneel and lie under the Japanese maple. Their ears move like small, articulating satellites: weed whacker, school bell, wind chasing trucks on the byway. I moved through this morning by rote: ate breakfast, stepped out to the balcony, drank tea in the sun. Now, I recline in the heat and listen to the valley while the sun beats down. Abbotsford says “Hush, sit, tan,” and I do, because that is what I have always done here on days like today. I turn my head and press my nose into my shoulder. The scent opens my memory. Flashes of past summer days interrupt the moment, and for a convincing instant I am stretched out on the padded lounger reading Nancy Drew, and then/again spritzing my hair with lemon water to help the sun blanch the colour, and then/again I am watching my sister oil her arms with tanning lotion, flip to her stomach and perform twenty-minute repositions of straps and strings.

It has been two years since my last visit to this 1970s split-level house on St. Moritz Way. I grew up here, yet the house looks completely different since it underwent a full renovation. Somehow it still feels like home in spite of the new layout. It’s home because it once was, and has remained, whether I like it or not, the standard of “home-feeling” against which I’ve measured all other places. The first time I walked through this house, it still belonged to the previous owners. There was a peek-through gap in the staircase leading to the basement that provided a glimpse of a workshop below. I remember crouching on the stairs and looking through, imagining Dad down below, working. After this first encounter, that secret peephole was everything of the house for me. It was the one place where I had engaged my senses—knees pressed into the stiff berber carpet, hands cupped around my sight at the peephole—and my imagination, spying on Dad. The experience lodged in my memory, becoming the first entry in my catalogue of this house.

Here, as with all other places, bodily apprehension makes places count. With each new sensory engagement, “space transforms into place” like a sketch acquiring detail. Arriving anywhere new, my mind combs through its catalogue of past experiences, weighing the new against the remembered. Where there is resonance, I feel at home. Where there is none, I feel estranged. Here, the estrangement is superficial—hardwood instead of carpet, grey stucco instead of white—and the overwhelming feeling of familiarity saturates my experience to the point of inducing habit: tea, book, tan. New becomes known, known becomes home. Between memory and encounter the essence of home emerges over time, developing with each new experience.