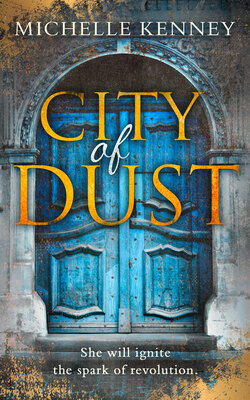

Читать книгу City of Dust - Michelle Kenney - Страница 13

Chapter 5

Оглавление‘Rye bread?’

I shook my head at Max, and glanced around our makeshift camp for Eli.

‘Seen Friskers?’ he signed as I made my way towards him on the opposite side of the clearing.

‘Max said he was here earlier,’ I reassured him, ‘testing the porridge for us before he slunk off. He’s more cat than anything else, I reckon.’

Eli grinned, clearly more concerned about an AWOL griffin than his own skin.

I scanned the jungle bushes, already glistening with the day’s heat. We’d left Arafel at dawn with enough provisions for a couple of days. After that we would survive on hunting skills and luck – Outsider basics.

My mind returned to the previous evening, when I’d discovered the haga was missing. I’d sprinted back to the Ring, but the meeting was already over, and the majority of villagers had voted to reject. And I couldn’t blame them, not really. Protecting Arafel rather than a group of Prolet rebels who could bring the wrath of Pantheon directly on our heads was logical. But, of course, none of them understood the real value of the Book of Arafel, which was why I hadn’t told them about its theft either.

It had been my idea to go rogue. There was no other choice for me, and Max and Eli were in from the start. Aelia had come to us in desperation. And if we mounted a rescue now, we would win the loyalty of a group of Prolets who knew a covert, underground route back into Pantheon. It was far from perfect, but our best chance of retrieving the Book. And I couldn’t help but feel Grandpa would want us to help the insurgents, come what may.

‘Grandpa used to say the Dead City is a day’s hike north-east,’ I signed. ‘We should be there by dusk, and most of the journey will be forested.’

Eli nodded. ‘It’ll be the farthest east we’ve ever been,’ he responded, frowning, ‘and the closest to the Lifedomes – without actually going inside.’

I nodded.

‘Although that’s not your plan is it?’ he added.

I grabbed his arm, and pushed him into the thicker bushes. The last thing I needed was Max guessing at my real intentions. It was only when the bushes opened out into a small scrub clearing, that I looked up into Eli’s guarded face, and felt a surge of guilt. The distance between us was hurting him. I’d been so wrapped up in my own frustration, I wasn’t doing anything to make it any better for my clever twin. My complex, insightful, sensitive twin who’d guessed Max’s feelings long before I had. And lately his closed nature and preferred solitary lifestyle had prompted a few more questions in my head.

I sat down on a banyan root, as Eli stooped beside the knotted tree, tightening a trouser binding. Seconds later, I felt a handful of leaves and grass being pushed down the neck of my tunic. Stifling laughter, I shook the foliage from my forest tunic and elbowed him affectionately.

‘I know Grandpa entrusted you directly with the Book’s safekeeping,’ he signed, taking a seat beside me, ‘but I know he wouldn’t want you to go back in there, not for anything or anyone.’

I frowned, feeling the lighter mood dissipate swiftly.

‘I also know Octavia wanted the cipher Thomas drew out on the treehouse floor. And that you figured out how the cipher worked … But you never shared anything else?’

He paused to run his fingers through his sandy-brown hair.

‘No wonder you and August had a thing,’ he signed, eyeballing me carefully. ‘You’re the same – neither of you trust anyone.’

I suppressed a retort. I’d never discussed my feelings with Eli, and his insight felt unusually cynical.

‘So what else aren’t you telling me? Does Max know more?’ he added.

I shook my head emphatically, knowing how much it had cost Eli to let Max come between us over the past few months, to relinquish some of our special twin bond.

He seemed momentarily satisfied.

‘Don’t you think Grandpa would want me to help you? That he’d want you to share the burden, especially now that he’s gone?’

A slow dread started creeping through my bones, as the promise I’d made Grandpa echoed inside my head. I’d given my word I wouldn’t tell another soul about Thomas’s research hidden within the Book of Arafel until the day I died. I’d already compromised that secret by trading information about the cipher’s existence with Aelia and August in return for their knowledge of Roman symbology. And now both Eli and Max knew about the cipher on the treehouse floor. But the fact that the Book of Arafel actually contained Thomas’s research notes was still a secret – well, it was until Aelia stole the Book.

I glanced down at my interlocked fingers, recalling the yellowed pages of nonsense lettering and interconnecting circles that always looked so like the scribbling of an imaginative child to me. The knowledge that it coded one of the best-kept secrets of the modern world; and that mythological creatures had actually existed, back in the aeons of time, had seemed so fantastical – but not any more. Since Pantheon, nothing surprised me.

And then there was that one particular faded pencil drawing, buried within Thomas’s notes. Its charcoaled lines had first spun out of the dust clouds in the Flavium when I thought all was lost. It was the moment I’d realized Thomas’s notes concealed a clue about an ancient burial ground for the unique creatures that had once walked the earth, information Cassius would probably trade his entire Roman battalion to own.

I squeezed Eli’s hand.

‘Isn’t the fact that Aelia has stolen the story of Arafel’s emergence from the dust clouds enough?’ I whispered.

I could tell by the slight lowering of his eyelids that I’d failed. I looked down at my leather-soled feet, knowing my loyalty to a promise was dividing us. Pulling us apart. Was it always going to be like this now?

A rustle of branches and raucous cawing saved the moment.

‘Friskers?’ Eli signed before rising to his feet and striding off in the direction of the call. Seconds later, the dense greenery parted and he re-emerged with the tip of an oversized hook beak just visible over his head. I smiled, despite myself.

The griffin always made me stare. Standing around two and a half metres high, its powerful lion forepaws were around the size of my mother’s cooking pot, while its blood-red eyes and vibrant gold plumage were brighter than any exotic bird of prey. But it was its hard, calcified beak, filled with a double set of serrated canines that magnetized me.

They were sharp enough to shred a human arm in seconds, but that was before Eli discovered griffins were living in a world of silence. He’d saved us all from the brink of death by using rudimentary sign language to communicate with the modified beasts and now, this particular creature could understand and respond freely.

Though it still skulked around like a moody, domestic cat.

‘If you were less conspicuous, we could have taken you with us!’ Eli signed to Friskers affectionately. ‘But I’ll tell you the same thing I told my beautiful, wilful Jas. If I’m not back in three days’ time, feel free to come and rescue me.’

He soothed the beast’s burnished neck feathers, which were gleaming in the morning sun, as it lifted its angular head to proclaim its loyalty. A couple of capuchins chimed in, and the griffin eyed the foliage with fresh interest. There was no doubt it had taken to forest life with ease.

‘It’s OK,’ Eli added with a smile. ‘I don’t really expect either of you to play the hero, not a lot for a handsome griffin to do in a city of dust.’

He dug around in his pocket for a couple of sweet hazelnuts. A natural carnivore, the griffin also seemed to have a taste for herbivore treats, and Eli made sure its diet was well supplemented.

‘Sun’s up, it’s time we got going!’ Max interrupted.

He disappeared as abruptly as he’d appeared, back in the direction of our small breakfast camp. Eli threw me a look that cut through every defence like an invisible Diasord.

‘Boyfriend got the hump?’ he signed, raising an eyebrow.

I flushed and stood up. ‘You know it’s not like that!’ I scowled.

Right now, I’d never been less sure of what we were, only that I’d made a promise that was haunting me.

***

‘We believe in natural order, respect for our place in the forest, and taking only what we need to survive.’

Grandpa’s principles rang in my ears as we hiked through the unknown forest in an easterly direction, and I wondered what he would say if he could see us now. Hunting in this area of the outside forest had always been strictly prohibited; it was too close to the Dead City and wall of the Lifedomes.

The dense, untouched foliage made for slow progress, but our hunting machetes sliced where our feet and hands struggled, and we were in good spirits, reaching the fringe of the forest by the end of the day’s hike. We trod cautiously as the trees began to thin, picking our route through a thicket of wild hawthorn with care. And although Friskers had followed us for some time, he’d chosen to retreat while the sun was still high. It seemed even a displaced griffin had better sense than to get within striking distance of the Dead City.

It was only when we finally glimpsed our first view across the landscape of the monolithic domes that we paused to agree final tactics.

‘We try for the city when the sun touches the horizon and regroup here, dawn tomorrow morning. Prolets or no Prolets.’

Max drew a white cross on a royal poinciana with a piece of natural chalk, his voice brusque.

I looked from him to my brother. A similar unease was etched into both their faces. No one from Arafel had ever been close to the perimeter of the Dead City ruins, let alone explored them. And yet we’d all heard the stories, and stared at Arafel’s scant pre-war pictures of impossibly tall stone trees that stretched on and up.

Less well known was the fact that a few of the more agile hunters, including Max and myself, had occasionally glimpsed the City from the highest branches of Grandpa’s Great Oak. The tree’s age meant its thinnest branches extended beyond the rest of the others, and it was from these reedier lengths that you could make out the north-westerly tip of the ruins. But it was only ever a glimpse, and from such a distance there was no sense of the layers of dust and ash – the remnants of the people who’d once lived there.

The years had done their work, and now the ruins were fighting a different enemy, the forest herself. I recalled the moment I’d stepped out onto Octavia’s balcony, and witnessed the endless broken landscape stretching out before me like a nest of grey vipers. Sleeping and waiting.

I repressed a shudder. Being fanciful about the Dead City wasn’t going to help at all. Our first aim was to locate the Prolets and bring them back to Arafel. We wouldn’t be popular, but burying our heads in the sand would buy only time, not a reprieve. And Eli didn’t need any further reason to think I was planning on a different course of action – at least not yet.

‘I suggest we eat up and rest while we can. Tonight we’re going to need our wit, energy, and all the luck of Arafel,’ Max muttered, turning away to make a small camp.

***

It was the absence of distinct birdsong I noticed at first. Almost as though they too sensed this was a place where life had sung its last song, where anything natural had been obliterated leaving only a hollow echo in its place. It was both mesmerizing and terrifying, making all the tiny hairs on the back of my neck lift in the breeze.

For a moment we stood there, the three of us, staring out at the distant charred landscape interspersed with the creeping determination of the hardiest plants, fighting to reclaim their birthright. It had taken decades before any life had been spotted from a distance, the effect of cataclysmic biochemical warfare having rendered this part of the landscape scarred beyond recognition. But slowly nature was showing herself to be the victor.

‘We stick together, no solo heroics!’ Max spoke softly just behind me.

He still hadn’t really forgiven me, but there was no misunderstanding him, and I felt the oddest sense of déjà vu. It was exactly what I remembered him saying in Pantheon, just before we faced Octavia’s guards and were separated.

I nodded at Eli who was slowly surveying the dusky ruins. My brother had never been suited to combat of any kind, and it was a wrench to leave the care of his injured animals to a trusted friend in order to secretly help his sister trawl morbid, ruined cities. I touched his arm.

‘You don’t have to come. Max and I can cope. Camp here?’ I signed.

He frowned, arching his eyebrows. ‘And wait for you two to run headlong into trouble because you’re too busy arguing? I don’t think so!’

He crouched to release an injured salamander he’d been carrying up his sleeve for most of the journey.

I glanced up and down the edge of darkening trees, like age-old sentries watching the landscape.

Light was disappearing quickly now, although it was only around suppertime in Arafel. I pictured Mum sitting by the cooking pot by herself, and hoped Raoul had gone to keep her company as he often did when we were hunting in the outside forest. I’d left Mum a note. She’d never have agreed to the plan, and probably wouldn’t sleep until we got back. If we got back. I pushed the thought firmly from my mind.

A barn owl hooted twice through the waiting quiet, like a siren. It felt significant in some way. And there was no reason to delay any more.

We took our places beside each other, and as I narrowed my eyes against the glare of the dying sun, I muttered a silent prayer. There were a good couple of kilometres of lumpy arid dirt separating us from the start of the Dead City sprawl. Three of us to bring sixty souls back.

It seemed a good return should we make it.

There were no guarantees, of course; no one knew what the ruined city of Isca Pantheon was really like. But we were better equipped than the last time I left Arafel. Although there were no Diasords between us, we’d brought weapons that we’d grown skilled at using every day of our lives: machetes, daggers, axes, bows and in my particular case, a certain well-used slingshot.

We started out together, and I noticed the cool dirt crumbling beneath my leather-soled feet straight away. This was a thin, recovering topsoil, seemingly like the one Grandpa and his forebears had to coax back to rich life. It made for quick, stealthy progress, and the three of us broke into an easy hunting sprint across the amber landscape, towards the ruins.

It was deceiving at first, the way the ground shifted, almost as though it could have been merely the impact of our running feet against the dehydrated earth; earth that hadn’t seen human feet for more than two hundred years. But then a pained cry razed the empty landscape, and the enemy was so close as to be laughable. The ground was moving. The cry belonged to Eli. And when I glanced in his direction, he was no long running.

I froze instantly, my eyes straining against the fading light until I could make out his crumpled form on the ground. My heart rate doubled instantly. We were tree-runners; we never fell.

‘Eli?’

My whisper died on my lips as Max caught my wrist.

‘Look at your feet,’ he forced through gritted teeth.

And there was something in his voice that froze me to the spot. I levelled my gaze, and fixed on the earth beneath my feet. The earth that moved. And now that we were stationary, I couldn’t understand how I hadn’t felt it before. The earth wasn’t just moving; it was writhing.

I peered harder. My mouth was as dry as the arid soil beneath my feet, and my blood echoed like a waterfall in my ears, but I was unable to break my gaze. Not until I made out the heaving mass of giant, overlapping pincers, just visible beneath the lumpy dirt; and their segmented tails, poised and ready to paralyse their ignorant prey at any given moment.

‘For the love of Arafel, fly!’ Max growled, as we lunged together, grabbing Eli and pulling him to his feet.

Then, between us, we propelled him over the remaining barren land at breakneck speed. I bit down hard as our feet flew, now fully aware of the heaving mass of scorpion topsoil crunching beneath our thin-soled shoes. We gave no thought to the noise we were making, or obvious profile we were cutting across the barren landscape. Our only thought was to reach safety as quickly as possible. I clenched my fist around Eli’s lower back. At this rate we could expect a personal welcome from Cassius himself.

It was only when the broken silhouette of the city outskirts loomed up out of the gloom that I allowed myself to hope. The ruin seemed quiet and still, but taking no chances, we made straight towards a large concrete boulder resting in the shadows. With one final effort, we half carried, half pushed Eli on top, before scrambling up ourselves. Then it was only us and the vast oppressive night.

‘Eli,’ I whispered, reaching across to my brother. He was curled up, motionless, and for a second blind panic clawed up my dry throat. Was he dead?

Then he rolled over and lifted an eyelid to consider me carefully.

‘First time I’ve ever considered de-friending Hottentotta tamulus.’ He winced, his breath slightly laboured.

‘You’re stung?’ I scolded, reaching into my rations bag for some of the medical herbs we carried on us.

‘Yes, I’m also winded,’ he complained. ‘My feet barely touched the ground in the last part of that run.’

Cursing, I scrambled in my leather bag. Two hundred years of living in a jungle climate meant we’d developed some natural antibodies against snake and spider bites, much stronger anti-venoms than our ancestors used to possess. All the same, the Hottentotta tamulus was one of the most venomous scorpions around.

I pulled out my water bottle. ‘Where?’ I demanded.

Eli rolled up his right trouser leg, revealing a raised red welt on the front of his calf. I tipped some cool water on a small rag, pressed some fresh meadowsweet into the wet patch and then placed it over the injury. He smiled gratefully, and squeezed my hand before taking over.

‘It’s not stinging so much already,’ he consoled. ‘Think I may have got lucky with a small one.’

‘Not sure any sized scorpion sting counts as luck!’ Max retorted. ‘And if this is just a warm-up for the Dead City, we’re gonna need so much more than luck.’

I nodded grimly. Max was right. This wasn’t a good start. Eli’s leg wasn’t life-threatening, and so long as there were no other visible signs of shock, his body was coping. But the effect on his leg would probably slow us for a day or two – time we could ill afford to lose. And then there was a prophetic feeling I couldn’t shake. If this had happened to Eli, just about the most popular human in the animal kingdom I knew, what chance did Max and I stand if there were more of them?

‘We move slowly and as a team,’ I said, trying to control my spiralling fear.

I hadn’t risked the wrath of Art just to become scorpion food. My head filled with his wise face. I hadn’t even told him about the theft of the Book of Arafel. There hadn’t been time, and I doubted it would change much, although he would have been sad and angry. But mostly I hadn’t told him because it would be like shining a light on my own ineptitude. I’d already broken my promise to Grandpa by letting others understand some of the legacy of the Book. Admitting to its loss felt like exacerbating my own sense of failure. Far better I put the situation right. Or at least tried to.

For a few minutes we remained seated in the shadows, recovering our breath while the voice of the Dead City reached through the shadows. It moaned. Not in the biblical sense, although in some ways I wouldn’t have been surprised; it was so much bigger and more oppressive now it loomed up in front of us. Instead, the eerie groan was of nature herself, creaking through the rubble alleyways and broken roofs, and whistling through every decrepit gutter. As if she was warning that nothing should ever breathe or live here again.

Silently, we examined the leather soles of our shoes, but somehow our slim goat-hide soles had protected us.

I threw a glance at Eli. His face was filled with the same quiet foreboding I was feeling. We all understood the dangers of the forest, and had learned how to combat the most cunning cats, ferocious boar and shrewd snakes. But a sea of scorpions was new to me. It had to be nature’s response to the arid conditions in this part of the landscape, and might explain why the Prolet insurgents had become landlocked in this crumbling shell of a city.

Silently, we bowed our heads together, an old Arafel custom to offer thanks for the sparing of a soul. There was no going back that way – that much was certain – and I couldn’t help but feel that this was the precise moment we were leaving Arafel behind. Was it for good? I pulled my trusted catapult from my leather pouch, and fought the sudden burning behind my eyes.

‘You think you can walk on it?’ I asked, as much to distract myself as anything else.

He nodded. ‘And if not, Max can give me a shoulder ride!’

I smiled as Max grimaced.

‘Yeah, right after you,’ he jibed. ‘Time to go?’ he added, crooking his neck to look into the darkness, while withdrawing a short, gleaming blade from his hunting belt.

I frowned. Like most hunters in Arafel, Max could handle a knife, bow and fishing spear with practised ease. But he was particularly gifted when it came to knives, often dispatching prey from as far as fifty metres away. His precision and brute strength also made him a formidable adversary in combat, but this was different.

I shot out a hand to pause his course, before loading a stone in my slingshot. Swiftly, I took aim and released so the stone flew through the broken archway into the darkness beyond. The hollow echo of the stone’s tumble filled the tense air, before it came to an abrupt standstill. My skin felt like a thousand scorpions were crawling across it, in some giant arachnid march. But there was no answer – nothing but the same chilling whistle of wind through the broken streets.

There was no more reason to hesitate.

Supporting Eli between us, we slipped off the stone and stole forward together. And as we passed beneath the crumbling Gothic arch and into the shadowed ruin beyond, I was immediately struck by a cloud of grey oppression, despite the green moss and hardy creepers.

The whistling moan of the wind was louder here, as though it belonged in the way life had once, whispering memories. Warning us. We stared around the ruined space in silent wonder. We’d made it; we were inside the Dead City. We were the first Outsiders from Arafel to have trodden here since the Great War, and we didn’t belong at all.

Swallowing, I tried to get my bearings. This first building was large and rectangular, with several broken pillars splayed across the debris-strewn floor. They must have once supported a high-vaulted roof, at least twenty times the height of our treehouse.

Briefly I wondered what purpose the space might have served, and then I spotted the parallel lines sunk into the floor a little way off. They were beyond rusted, and almost obscured by overgrowth, but I’d studied the old world enough to know I was looking at what our ancestors would have called a railway station.

‘Toxic boxes on wheels … They choked the earth and burned precious resources, making men fat and lazy …’

I could hear Grandpa as though he was standing next to me, and his words seemed to resonate eerily in this overgrown crypt. The space rang with the echo of a thousand impatient footsteps that no longer bore any connection to our forest community. I felt my hands grow clammy. Our ancestors’ obsession with speed and technology hadn’t brought them freedom; it had trapped them for all eternity.

‘Let’s move,’ I whispered to Max. ‘There’s no living soul here.’

Eli’s wan face gleamed in the thin moonlight, and I knew without asking that he, too, could hear the dead voices clamouring in this place.

Max threw us both a cursory glance before stepping out in front, his sure feet cutting across the echoes, and pushing back the ghosts. He cut a diagonal line across the floor towards another crumbling stone arch, before beckoning that we should follow. We traced his path across the cracked, overgrown concrete to pass beneath another wide, intact arch with some kind of long oblong set into the wall. Up above, there was a series of smaller oblong boxes attached to the ceiling, some broken and dangling. I guessed them to be old-world computers of some sort, but to me they looked like nameless gravestones.

We hurried beneath the thick arch, and I breathed a sigh of relief when the crumbling railway façade opened out onto what must have once been a long wide pavement, scattered with creeper-clad broken stones.

Concrete city foundations had prevented a lot of thick, upright growth; and a surprisingly clear old road ran parallel with the railway, lined with blackened, toothless buildings. Further up the road there was a circular juncture with several similar-looking routes extending from it like a spider’s web.

I glanced at Max in disbelief. It looked as though there was far more of a city skeleton remaining than any of us had ever expected, and the Prolets could be anywhere.

‘OK, steady progress, that’s all we need!’ he reassured, his gaze lingering on Eli.

I smiled tightly, conscious of how our footsteps seemed so intrusive here, a city that had once known the pounding of so many feet. And the sheer scale of the structured ruins meant there were countless roads and decaying buildings to scour. Even if we split up it would still be an impossible task to achieve in one night.

And yet we were here, and there was no going back.

The three of us started up the middle of the crumbling, overgrown road. Although the sun had long disappeared, everything was draped in a lazy veil of moonlight and clinging cloud. I fought a shiver. Even though the darkness was our friend, I felt more exposed now than I ever had in the outside forest at night.

My ears were straining and senses on high alert. There were enough walls remaining to differentiate between the buildings where people had once traded food and goods, and those that had offered shelter and a home. But there was a something else too, a feeling that the shells weren’t quite as lifeless as we first thought. There was a scuffle here, a rustle there, and always the sense that we were intruding, trespassing on hallowed, sacred ground.

Gritting my teeth, I focused on the sound of our feet on the cracked concrete, pushing all fanciful notions to the back of my mind. But Eli getting hurt so soon had sent a fracture haring through my confidence. Eli. I’d already come too close to losing him in Pantheon. There was no way I could risk either him or Max getting hurt again because of me. It would be worse than getting hurt myself. Which was why I knew that when the right moment came, I was headed to Pantheon. Alone.

We stole on, alert to every new noise. Eli was managing to walk unaided, but I could tell his leg was throbbing, despite the meadowsweet. I fumbled for my rations bag, intent on finding some willow bark for him to chew to dull the pain, only to graze my own shin against a dark object protruding between two broken slabs of concrete.

I yelped and reached down.

‘What’s the matter?’ Max whispered, turning to see why I’d paused.

I scowled down at the offending object, still rubbing. It was made from metal, and layered with years of grime and dirt, but with a little effort I could just make out black lettering running along its length.

‘Queen St,’ I read, frowning.

‘Queen … sting? Queen … strop?!’ Max tested carefully.

I pulled a face to cover my relief. It was the first real reference to our fight since leaving Arafel. I’d hurt him, I knew that, and in some ways I’d understand if he never spoke to me again. At least not like that. Humour was always a good, safe place for us.

But just as I opened my mouth to retort, Eli started signing frantically.

‘Something up there! Inside!’ he gesticulated rapidly, pointing up at the charred remains of a blackened second-floor window, just above us.

It was Max’s turn to scowl. ‘What kind of something?’ he signed awkwardly.

‘Not sure,’ Eli signed, ‘but it moved … a shadow?’

‘This place is full of shadows!’ Max exploded.

I glared at him. ‘If Eli says he saw something, we ought to check it out!’

We all stared up at the concrete hole that had once been a large formal window. It looked as black and uninviting as any of the charcoaled, deserted buildings.

‘Protect it with your life, Talia, come what may.’

I tried to pretend I hadn’t heard, but he was there, echoing around the edge of the cool February breeze. Cursing softly, I sprinted up the cluttered stone steps that must have once been a formal entranceway, before I could change my mind.

And as soon as I passed beneath the large grey entrance arch, I knew this building could never have been any ordinary shop or house. Even dressed in murky shadows, it was big, with a white, formal staircase that gleamed and stretched upwards in front of me. Everything was covered in years of dust and scorched debris, and half the ceiling was completely missing exposing a finely balanced balustrade. At the top of the first white flight, watching over years of debris and dust, was a single lonely sculpture. Its athletic silhouette shone in the darkness like an angel of war, and it was only when I finally made out its name that I allowed myself a smile.

‘Prince Albert … and about time,’ I whispered to myself.

‘Huh?’ Max whispered, stepping up beside me.

‘Nothing,’ I dismissed, carefully eyeing the curve of the balustrade from the first flight to a precarious second flight with the central rises missing. I flexed my fingers; I had my route.

Without hesitating, I ran lightly towards the staircase, took hold of the cool stone and leapt, knowing Max would have to follow much more gingerly given the fragility of the structure. It wobbled, and a shower of debris fell from the landing above us, but I didn’t pause. It was a tree-runner’s number one rule: never doubt. Doubt and you fall, Grandpa would say.

Within seconds, I was standing opposite the heroic Prince Albert, and I held my breath as I followed the shaky bannister around. The second run was much steeper, and the middle of the stone rises were missing, which meant no second chances. I narrowed my eyes, and tiptoed up until I reached a point close enough to leap. Then I was flying like a squirrel monkey, claws outstretched, until they grazed the old wooden first floor.

I drew myself up to standing, letting my eyes adjust to the dingy gloom. This part of the building seemed to have survived quite well, and there was a large open corridor leading in both directions.

After only a moment’s consideration, I turned down the left corridor. Both walls were lined with large glass cases that had somehow, by the luck of Arafel, escaped the effects of the Great War. Curiously, I peered into a cabinet labelled Gladiatorial Artefacts, only to recoil as a spiked head with black, eyeless holes in the centre leered back at me.

‘Boo!’ a voice whispered.

I gasped before rounding on Max with a glare. He grinned mischievously while rubbing the glass to remove two centuries of dust.

‘We’re in one of those places they used to display old stuff – a museum, isn’t it … Miss?’ he teased.

I turned back to the display. I didn’t want to give him the satisfaction of knowing he’d rescued me from the memory of Cassius riding out into the Flavium; a monster on a black mount wearing similar headwear. And as I gazed, a tiny black sign at the bottom of the glass case caught my attention: Roman Gladiatorial Helmet – worn by Rome’s elite gladiators. I grimaced.

Of course we were in a museum. Exeter Museum. Or the shell of it anyway. It would also explain the sculpted figure halfway up the steps. It seemed incredible that anything like these silent exhibitions had survived the most cataclysmic war the earth had ever seen. They were like treasures left beside a grave.

‘The room’s up ahead.’

Eli suddenly hobbled out of the grey, his signing jerky and stressed.

I sighed. So far my attempts at protection were proving futile.

‘The back stairs were complete,’ he offered simply.

Inwardly I cursed for not having the foresight to check for another set myself.

‘You should have waited below,’ I hissed. ‘Thought we agreed no heroics?’

Two sets of eyes danced ironically, and I spun on my heels, swallowing my retort.

There was less natural light in this part of the corridor, and the air was rank. Something with a thick tail and muffled squeak ran in front of me, making the hairs on the back of my neck strain. There were plenty of nocturnal rodents in the forest, but the shapes that moved in this ruin somehow felt much less animal than at home. I swallowed, and forced my feet forward towards the large closed door at the top of the corridor. It was the room we’d pinpointed from the street outside, where Eli had seen a shadow move.

Max leaned forward to listen, and for a moment all I could hear were three hearts pumping so hard I was sure anyone inside had to know of our presence instantly. He shook his head, and the strange tingle spread across the back of my shoulders and down my arms. Slowly, he reached out and turned the door handle. His knuckles gleamed, despite the lack of light, and afterwards I realized it was because he was gripping so tightly. Then it swung inwards to reveal a huge, shadowy room, half open to the stars. Full of eyes.

‘Get back,’ Max whispered hoarsely but not before several huge black, bulbous shapes inclined their skinny heads towards us. The stench hit us like a wall. It was putrid rotting faeces and my world closed in, taking me back to Pantheon’s tunnels in a heartbeat.

We stumbled backwards through the doorway, my thoughts running wild. Had Cassius already unleashed monsters from the tunnels? Could we have happened upon a pack of sleeping strix?

Nausea reached up my throat, as my clumsy movement sent a loose stone scuttling across the floor. There was a moment’s poignant silence, and then the air was filled with opal hunting eyes, threatening hissing, and the deafening beat of large, heavy wings.

Pandemonium ensued, but somehow I was conscious of Eli forging forward in the opposite direction. I made a grab for him, but clutched only thin air as he disappeared into the murky whirlwind inside.

‘Eli,’ I yelled, holding my arms high in front of my eyes to protect them from the thick, swirling dust.

Eli was the most gifted animal whisperer I knew, but what if these new creatures were of Pantheon’s design? I recalled the effort it had taken to calm the manticore and molossers, and felt my panic swell.

Then, just as suddenly as the chaos had erupted, it fell unnaturally quiet.

‘Eli?’ I whispered again, my chest thumping so hard I thought it might explode.

Although my brother couldn’t hear me, he usually sensed when I called him. But there was no response, and the still black was more than I could bear. So, swallowing my panic, I crept inside.

For a moment, I was conscious only of breath, of living bodies other than our own sharing the same dark space. Then as the moon moved out from behind the gunmetal clouds, and the shadows became low-lit pools, my gaze was drawn to the centre. Towards Eli.

He was seated cross-legged on a central, raised dais that must have originally been some sort of displaying table; while a pack of waist-height, hairless birds scavenged around him. They were huge, skinny, and beyond ugly.

But they weren’t strix.

Holding my breath, I edged closer. The birds clattered around the floor, occasionally raising their heads to sniff the rank air. With featherless blue-grey heads, brown ruffed necks and tapered wings, they were clearly birds of prey; and at more than a metre tall each, they were also birds to respect. But no creature on our free-living planet could resist Eli, and right now they appeared calm enough.

‘What are they?’ I signed.

‘Cinereous vulture,’ he responded studiously. ‘One of the two largest, vulturous species of birds on earth.’

A brief memory of the giant, clawing strix flickered through my head, but I knew he was talking about birds outside Pantheon. Apex predators of the natural world.

‘Have been known to eat flesh, but much prefer their dinner deceased.’ He smirked as Max stepped up beside me.

‘Yeah, well … when you’re done having tea with the local wildlife, we’ve a job to do,’ Max forced out, scanning the room.

I followed his gaze and scowled as more silhouettes of stuffed, old-world creatures took shape within the gloomy darkness. A towering elephant and giraffe made the vultures look little more than pecking chickens; while their glassy, yellowed irises gleamed lifelessly from their mottled skins.

I dragged my eyes away. The stuffed creatures’ stare was almost worse than the vultures’ clear suspicion that Max and I were a potential threat to their new king. I glared at my brother, who sighed before standing up to address the unsavoury group with a series of crude gestures. Then he slowly backed away, taking care to push us through the doorway first.

‘So, what did you say to them?’ I signed, once we were back on the road outside.

‘I told them my friends were a little chewy; but if they stuck around I knew of a few others who were rotten to the core,’ he responded blithely.

And right on cue, a dozen dark shapes soared effortlessly out of the window and into the smoky sky above.

I scowled. Ravenous, cinereous vultures weren’t exactly my idea of the perfect cavalry.