Читать книгу Children Belong in Families - Mick Pease - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

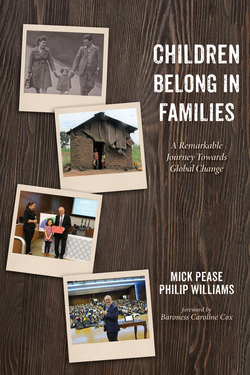

1. The Mystery Man and the Baroness

ОглавлениеMick, this can work in Brazil!

“You have five days to leave the country.”

My Portuguese may not have been the best, but I understood that much. I felt the impact even more when the federal guard scribbled in my passport and pressed the rubber stamp home. Bam! One curt comment, a single jab, and our plans were squashed, our work at an end.

Brenda and I were working at a Brazilian children’s home on tourist visas. We had visited friends in Paraguay and were crossing the border on our return. Like many others, we had seen TV coverage and read news reports of the murders of street children. Restaurant owners, hoteliers, and shopkeepers were hiring armed men to rid the streets of nuisance homeless kids. They called them “the disposable ones.” Off-duty security guards, policemen even, were paid to execute these kids by night. Bang! A bullet in the back of the head, the body dumped on waste ground. No ID, no birth certificate or documents. No name.

These reports shocked the world. They shocked us too. We had to do something. Our two boys had grown up. Mark was studying and Kevin developing a plumbing business. We now had the time and opportunity to try and make a difference. I took a year’s leave of absence from my job as a social worker with Leeds City Council in the north of England. Brenda left her administrative job and we set off. The boys moved into the house and we put everything on hold.

Here we were, six months in, and the whole thing had suddenly collapsed. We were gutted. “Don’t worry,” everyone told us. “This is Brazil. They are so laid-back here. All you have to do after three months is ask the federal police whether you can stay longer. Then, after six months, you can cross the border to Bolivia or Paraguay and come back again. It’s a formality, a quick stamp on your passport and the visa is extended. Everyone does it, missionaries, aid workers. It’s no big deal, no paperwork, no fuss, no questions asked.”

Yes, this was Brazil, but this time, questions were asked. What did we think we were doing, crossing into Paraguay and then back again?

“We have been visiting friends.”

We genuinely had. We stayed a week with friends in the capital Asunción, unlike some aid workers on tourist visas who simply crossed the border, turned around, and walked back into Brazil.

We had crossed the border at Foz do Iguaçu where the conurbation extends as Cuidad del Este on the Paraguayan side and traveled onward by bus to the capital. Now we were stopped at the checkpoint as we tried to return.

“You can’t do this,” said the federal guard. “You cannot renew. You have five days to leave the country.” Stamp.

We exchanged very few words as the coach rumbled through the night and all the next day toward São Paulo. For twenty hours the vast Brazilian landscape rolled by; hills, plains, cities and settlements, pockets of forest. We were in no mood to enjoy the views, no mood even to talk. We had to leave Brazil and had no idea what we would do next. We both felt stunned, let down, abandoned, and alone.

The staff at the missionary organization we worked with were not at all perturbed.

“Don’t worry,” they said, “This is Brazil. We have contacts, we can put in a word for you. It’ll soon be sorted out. Leave it with us, we’ll go into the city and speak to the authorities.”

Days passed and no word came. We carried on as if in a daze, caring for the kids we’d come to know and love. We played games with the older children and washed and fed the younger ones. We gave them a structure and routine to establish the secure boundaries children need. Most were just ordinary kids. What they lacked was personal attention; a family atmosphere and environment. We loved those kids. I had spent weeks repainting the rusty old climbing frame in the play area. We both spent hours with Matheus, a toddler with hydrocephalus. We talked to him in his cot and pulled faces to make him laugh. Every day we took him out of his cot to learn to walk. Eventually, he reached the children’s playground and climbing frame, gurgling and chuckling with delight. It was this kind of interaction and personal connection that made it all so worthwhile.

People often talk about a “calling,” a sense of vocation. Brenda and I had felt it since we first met but had no idea at that time how this would work out. She was a farmer’s daughter from Devon in the rural southwest of England. I was a Yorkshire coal miner from the industrial north. I left school with no qualifications and no prospects. I had no interest in learning or education. We both came from devout Christian families and met at an annual preaching convention in Filey on the Yorkshire coast. It was there that I sensed some kind of “call,” an impression that I wanted to do something more than simply earn a living, something that could make a difference. From our particular church backgrounds, the expectation was that this would involve missionary work or church leadership. Neither of us had any desire to do such things. All we knew was that we wanted to do something. On the strength of this vague impression, we left our mining village and enrolled at a Bible college in the English Midlands. We had no prior academic qualifications and no idea what we were going to do afterward.

After Bible college we worked for three years as houseparents in a children’s home. From there I would go on to qualify as a social worker, specializing in child protection, adoption, and fostering.1 Gradually we began to develop a clearer idea of what the “calling” might involve; something involving children and families.

So here we were, in Brazil, fulfilling what we then believed to be the outcome of that “call.” Hands-on intervention. Working with street kids in a rescue mission. It all seemed to fit our expectations. Suddenly it was all coming to an end.

We had come to a Christian missionary complex in São Paulo State. I had been to Brazil before, initially to Belo Horizonte in 1994 at the invitation of YWAM (Youth With A Mission), a short-term mission agency that was developing an interest in issues around adoption. They wanted me to tell them more about it, how it worked in the UK, how it might be developed in Brazil. I returned the following year, imparting more information, meeting missionaries and social workers. On those occasions, I visited during my normal vacation allocation from Leeds City Council. Then, in 1997, impelled by the news of street shootings and murders, Brenda and I both came intending to stay for a year, unpaid, to try to make a difference.

We had written to some twenty-five missionary or development agencies offering our services. We wrote to all the Christian charities we could find which offered some kind of child or family care. The response opened my eyes. Most replied, but in each case, the response was broadly the same. What could they possibly do with a social worker? I wish we had kept those letters. A quarter of a century on they would appear even more outrageous than they did at the time.

What were they telling us?

If you are a car mechanic, we could use you in the mission field. If you are in primary health care or are an engineer, we could use you in the mission field. If you are an expert in agriculture or irrigation, a bricklayer and can build, a teacher and can teach English—we could use you in the mission field. But a social worker?

Yet every one of these organizations had some form of work with children or families. That was the very reason we had approached them. What did this mean? That if you were any Tom, Dick, and Harry you could work with kids? That if you were a social worker they wouldn’t know what to do with you? A bricklayer or a car mechanic, then yes, we can use your skills. We deliver health care so we could certainly use a nurse—but a social worker? You don’t have to be a social worker or have any qualifications or experience to work with kids.

I found this massively insulting, but quite apart from the affront to my professional dignity, there were more serious implications. What did this say about the level of professionalism involved? It struck me then and it stays with me now. I realized that many of the people working with children through mission, aid, or development agencies were doing so with good intentions but without the practical or professional skills required. They were working from the heart, but with no real knowledge of how to respond to kids suffering from trauma or loss. The attitude seemed to be, “Right, you are a parent yourself. You understand kids.” But there was no real insight that this in itself was not enough. These kids had particular problems. They were suffering from abuse and neglect. They needed specialist help. Something had to change.

It was the day before we were due to fly back to the UK. The leaders of the mission complex had made inquiries on our behalf.

“There’s no more we can do,” they told us. “You will have to fly back home. But you can always come back. Apply for missionary visas, come back and join us . . .”

I lent dejectedly on the metal windowsill of one of the bare, simple office rooms and gazed out over the dusty parking lot. A man in a white shirt was walking across it. He didn’t look Latin American, but that was not at all unusual for multicultural Brazil, particularly within a missionary complex with regular visitors from around the world. What was unusual was how, when he looked up and saw me, he addressed me in a British accent.

“You alright?”

“Not really,” I sighed, my dejection blunting the surprise at hearing a familiar accent. In many countries, including Brazil, people who could speak English often spoke it with an American tinge.

“Why?”

“It’s a long story.”

“Well, do you want to tell me about it?”

We spoke for a few minutes through the window then the stranger asked me to come down to talk further in the parking lot. I did so and I told him who we were, why I was feeling so downcast, and asked him who he was.

“Does it matter who I am?” he said enigmatically. “I want to hear your story.”

We spoke for a long time, maybe up to an hour. I told him how we had come to work with street kids and how our plans had come to an abrupt end. He must have sensed my irritation and frustration. It was clear he understood it, but he also encouraged me to consider the wider context, to put things in perspective. So many aid workers or missionaries came in thinking they had all the answers. They tried to impose solutions from outside. Instead, they should work alongside and in step with the cultures and societies of the host countries themselves. This was their country, their history, their culture.

After a while, he stopped me and said, “I don’t know why I am listening to you, but I feel a prompting—and I believe it is from God—to hear you out some more. I’m busy right now, but I would like to invite you and your wife to my apartment this evening. We can speak for an hour perhaps. Seven o’clock?”

I accepted his offer. We knew the area where he was staying, accommodation for visitors and for missionaries who had bought land and built houses for themselves. I went to tell Brenda, realizing as I did so that I did not know his name.

We turned up at the mystery man’s apartment at seven o’clock as arranged. As evangelical Christians, we were familiar with prayers and “promptings.” We also knew that there were visitors on-site and we had even heard talk of a delegation from the British government visiting our part of Brazil. We were intrigued. Who was this guy who had invited us around to talk?

“You can call me Sam,” he said. “I work for Baroness Cox.”

Baroness Cox? We had heard the name but knew little about her. We knew she had a peerage and sat in the House of Lords, the upper chamber of the UK Parliament. Beyond that, we knew nothing at that stage, although she was to become well known for her humanitarian work and advocacy in trouble spots around the world.2 She was in Brazil to receive an award from the government in recognition of her work.

“So, what do you do back home?” Sam asked.

“I am an adoption and fostering social worker.”

“And what do you do as an adoption and fostering social worker? What does it involve?”

“Well, I investigate and assess if children are safe where they live. I’ve been a residential social worker and seen how it works in the UK. Here in Brazil, I’ve seen that a lot of the kids in care are there not because they are bad kids, but because people have given up on them or because there’s not been another option where they can live. In the UK we wouldn’t place those kids into children’s homes because it’s not best for them. Instead we look for substitute families, either foster carers or adoptive parents. So why is it that here in Brazil they are hanging around in children’s homes forever and a day and, in some cases, horrible ones at that? It’s something I’ve observed since we’ve been here and I think there is another way.”

Sam listened then asked if we could pray. He said a short prayer asking that things would become clear for us and that we might have wisdom and strength to make the right decisions.

After he prayed, Sam looked up and asked, “You are leaving tomorrow?”

“Yes, in the afternoon. Our bags are packed and we are leaving for the airport after lunch. So, tomorrow morning we are going to say goodbye to the kids. We don’t know whether we will be coming back.”

“Baroness Cox and I are having lunch with the leaders of the mission in the refectory tomorrow,” Sam said. “I’d like to invite you to join us. Then the van can take you to the airport.”

The next day, we said goodbye to the kids. It was an emotional parting. We had grown very fond of them, particularly little Matheus and his sister, so brave and determined despite his condition. We pulled up outside the refectory in one of the mission vehicles. Leaving our luggage outside, we entered the long canteen to find the mission leaders, Sam, and the Baroness at one of the tables. She looked homely and very ordinary, not at all as we expected. It’s not every day that a former miner and a farmer’s daughter get to meet a Lord or Lady. They beckoned us over.

“How do I address a Baroness?” I asked as we were introduced.

“Just call me Caroline,” she said with a reassuring smile.

We both sat alongside Lady Cox. “Sam has told me all about you,” she said, “Now you tell me why you are here.”

We told her our story over the next thirty minutes as we ate our lunch. I repeated the observations I’d made to Sam about the lack of fostering opportunities in Brazil. Once we had finished she said, “Now, here’s what I think you should do. Go back and apply for a missionary visa and once you’ve got one come back here. But, Mick, don’t work directly with the children as you have up until now. Instead, conduct some research into why fostering isn’t happening in Brazil as it is in the UK and other countries. Once you have done that, you can see whether you can start to introduce foster care into Brazil.”

My first thought was, “Me?”

Who was I to do this? I don’t have any money. I don’t have any contacts. I’ve never done this before. I don’t know how to go about it.

I felt like Moses in the story of the burning bush when God called him to go back to Egypt to urge Pharaoh to release the Israelites from captivity.3 What if they don’t listen to me? Don’t send me. I’m not eloquent. I can’t speak that well.

“I’m telling you now,” said Baroness Cox, “If foster care isn’t happening in Brazil and if abandoned or homeless children can’t go back to their families, there have to be ways to find alternatives. With your professional background and experience, you can help to identify what those might be.”

So, we left the refectory and returned to the van for the drive to the airport. We did not see Baroness Cox again until she invited us to meet her at the House of Lords in 2017 although we maintained occasional contact by mail. I would meet Sam again later in equally intriguing circumstances.

All that lay ahead. For now, we flew back to the UK energized. Perhaps we hadn’t got things completely wrong after all? The answer had been there in front of us and we hadn’t noticed it. We had been doing the hands-on care, but really, we should look to influence things at a wider level. With my social work background and training, I could engage with other social workers, with academics and the judiciary, with policy makers and shapers.

We left the color and vibrancy of Brazil to return to a dank, dark English November. We moved back into our house where Mark and Kevin had been staying with a student friend. They weren’t expecting us back so soon. Brenda was struck by the enormous bright yellow Homer Simpson poster on our living room wall that had replaced a reproduction of a classic painting!

We were part of a lively church in Leeds. They were very supportive and even took up a collection to pay for our return airfare. We explained what had happened, why our year in Brazil had been curtailed, and began to outline what we planned to do next.

I was buzzing with ideas about how to proceed. As Christmas approached I was so preoccupied I found I couldn’t get into the spirit of it at all. Brenda could. She was pleased to be home. She had missed the lads and family and suffered ill-health for much of our time in Brazil. The accommodation was basic, the climate humid. At one point, she suffered horribly with a tropical intestinal worm until the Brazilian health services removed it. She was understandably relieved to be home. We had wondered whether our year in Brazil would lead to us living there longer term, working directly with street kids. Now we could see a way that was potentially more effective. With a missionary visa, I could return to carry out the research and advocacy work that Baroness Cox recommended. I could deploy my skills and expertise in a way we had not considered before. We had become too embroiled in meeting the immediate emergency needs. Now we could step back, take stock, and begin to address the broader issues. I now understood I had to work with those in positions of influence.

We left Brazil in late November 1997. By early February 1998, we were back. The intervening months were a whirlwind. We had been back and forth to the Brazilian embassy in London, sorting out visa requirements. I had to get the police checks done all over again, even though they had already been completed previously. I knew the procedures and how to lobby at the most senior levels to process the paperwork as soon as possible. There was no time to waste. We only had six months before my leave of absence expired and I returned to work.

During those last months in Brazil, I had meeting after meeting. I was now operating outside the faith sector, engaging secular agencies and authorities, judges, psychologists, and academics. I addressed groups of magistrates, senior officials, and administrators. People heard I was there talking about foster care as an alternative to institutional care. They came looking for me. They wanted to hear what I had to share. I am often asked how that came about. How an unknown social worker, a former miner from the north of England, found himself dealing with elected officials and senior authorities, initially in Brazil and then around the world? How did I get the introductions? Why did they want to listen to me in the first place?

I can only say that it happened and that it happened very quickly, far more quickly than the painfully slow process of implementation and change. There was an openness and candor among the Brazilian professionals and a fascination with the British fostering system. In England and Wales if it is considered unsafe for a child to remain at home, local government tries various measures to improve the situation. If nothing changes then the local authority applies for a court order to remove the child from parental care. An independent social worker and lawyer are appointed to ensure the child’s views are central to any decisions made on their behalf. The judiciary is no longer involved once the court order is issued unless there is any need for further legal changes. The local government is responsible for all decisions, where a child lives, who they see and their overall welfare. In Brazil and some other countries there is a tendency for the judiciary to remain involved after issuing the order. They take active oversight of the care process and a child may not be fostered without their consent.

The Brazilian legal system differs from that of English-speaking countries. If I were to stand any chance at all of influencing policies and practice, I had to reach the judiciary. I had to find a platform. I had to earn the right to be heard. I had to understand the system if I was to help influence change.

My main contacts during my previous visits were with missionary organizations. They had dealings and contacts with the authorities of course, but the connections I now made happened independently. The most significant of these were with Isa Guará and her colleague Maria Lucia in São Paulo. Isa held a senior position in the city’s social services working with older children. Maria was a child psychologist and research academic. They invited me around to Maria’s home at ten on a Saturday morning, so I beat my way there by bus through the bustle of the sprawling city. We were there the rest of the day, talking excitedly well into the evening. Both women could speak some English and could understand far more and between that and my very basic Portuguese we were able to communicate.

“Tell us about the English system,” they said. “We want to know all about it.”

I explained that it was not my intention to promote or recommend a British approach over any other. Our system was far from perfect but it was consistent and there were aspects they might find helpful. For all its flaws, the British system was based on the premise that children belong in families, not institutions. The UK, along with most North American and European countries, had moved away from institutional solutions in favor of family-based care. All the evidence showed that children placed with foster families or with adoptive parents, irrespective of economic circumstances, fared better socially and educationally than those brought up in institutions.4

I related how I had worked in the residential care system and knew it from the inside. My role as a social worker was to find safe and secure family-based care for children unable to live with their family, either with foster parents or through adoption. I told them how I would arrange background and safeguarding checks, how the legal requirements operated, what support and training were available for foster parents.

I told them what I had observed of social work education and training in Brazil. There was nothing I could add on the academic and theoretical side. Brazil has universities that rank among the best in the world5 and Universidade de São Paulo is reckoned to be the best in Ibero-America.6

Social work education in Brazil was stimulating and academically rigorous yet often with little scope for students to gain practical experience. As a child psychologist, Maria knew all the accepted and standard texts and theories used the world over. The pioneering work on attachment theory by John Bowlby,7 later work by American and Australian practitioners—none of this was new in Brazil. The issue was not the quality of social work education but the lack of opportunity for application.

Competition for places at the higher quality, publicly funded universities is intense. A third of Brazilian graduates study at private or for-profit institutions. These run courses during the evenings as well as daytime so that people can work and study at the same time. It is common for a Brazilian student to work from 7:30 a.m. to around 6 p.m. and then spend from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. in lectures and tutorials. There are few opportunities for practical fieldwork in disciplines like psychology and social care. Students work to support themselves unless their parents can afford to do so and this limits the opportunity for practical placements and hands-on training.

Fostering was virtually unknown in Brazil at that time. Isa and Maria were keen to hear my experience of it in the UK context. Adoption was better known but associated by many with international adoption by wealthy foreign couples. The situation was complex; so many barriers, so many obstacles. I had a lot to say yet Isa and Maria Lucia heard me out. I was in full flow when Isa Guará leaned forward and held up her hand.

“Mick,” she said. “This can work in Brazil!”

1. Fostering and adoption practice inevitably varies from country to country. For example, fostering and adoption are increasingly seen in the US as a continuum and, according to a recent UK government review, 40% of the approximately 135,000 adoptions in the US each year start as fostering placements (Narey and Owers, Foster Care, 96). In contrast, very few fostering placements in England convert to adoption. According to government statistics, as of March 2017 there were 72,670 children in care in England, 74% of which were in fostering placements (UK Government, Children, 8). In 2017, 4,350 children in care were adopted, falling 8% from 2016 (Ibid., 13). A high proportion (86%) of children adopted were under three years old (Ibid., 14). Figures for Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland are recorded separately.

2. Baroness Caroline Cox of Queensbury, born in 1937, is a crossbench member of the UK House of Lords. She received a life peerage in 1982 and was deputy speaker from 1985 to 2005. She is CEO of Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust and a patron of Christian Solidarity Worldwide, acting as its president until 2006. She is the subject of two biographies: Boyd, A Voice for the Voiceless and Gilbert, Eyewitness to a Broken World.

3. Exod 2–3.

4. The detrimental effects of large-scale institutional care on child development have been documented since the early twentieth century. The American behavioral scientist Henry Dwight Chapin used statistical procedures to chart critical periods of social development across institutionalized infants at a time when the mortality rate in some US orphanages approached 100 percent (Gray, “Henry Dwight Chapin”). John Bowlby and many others reached similar conclusions in the mid-twentieth century. More recently, in 2007, the Bucharest Early Intervention Project compared the developmental capacities of children raised in large institutions with those in families and foster care. The study found shocking evidence of impaired physical development as well as lower IQ and higher rates of social and behavioral abnormalities (Nelson et al., “Caring”).

5. See the QS BRICS University Rankings 2018 at https://www.topuniversities.com/.

6. The university has featured among the top hundred worldwide in various league tables, University Ranking by Academic Performance (URAP), and the Times Higher Education and QS World Ranking tables.

7. John Bowlby (1907–90) was a British psychologist best known for his pioneering research into child development and issues of attachment and loss. He was born into an upper-middle-class family and, like many from that background at that time, was largely raised by a nanny and sent away to boarding school. He had little interaction with his mother when growing up. During the Second World War he carried out significant studies on children separated from their parents which led to his later groundbreaking development of attachment theory. Bowlby’s research explored how children become attached to significant carers or “parental figures” when separated from their birth parents. His findings laid the foundations for later research and childcare practice. His best-known works are Child Care and the Growth of Love (1965) and Attachment and Loss, vols. 1 (1969), 2 (1973), and 3 (1980).