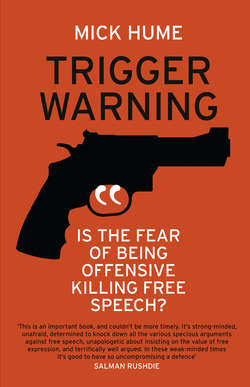

Читать книгу Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech? - Mick Hume, Mick Hume - Страница 9

‘Je Suis Charlie’ and the free-speech fraud

ОглавлениеFree speech is threatened on two fronts: occasionally by bullets, and every day by buts.

Copenhagen, Denmark, 15 February 2015. A meeting in a café to discuss the issues of free speech and blasphemy, just over a month after the massacre at the Paris offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. Inna Shevchenko of the Ukrainian feminist protest group FEMEN opens the panel discussion, talking about her relationship with the cartoonist Charb – Charlie Hebdo’s editor – and their shared insistence on their right to freedom of expression (FEMEN are famous for protesting topless).

Shevchenko gets to the nub of the argument: ‘I realise that, every time we talk about the activity of those people, there will always be, “Yes, it is freedom of speech, but …” And the turning point is “but”. Why do we still say “but” when we …’ At that precise moment her speech is ended by the sound of sustained gunfire from outside the meeting.1

The timing of the Islamist gunman’s attack on the Copenhagen free-speech meeting was so precise it might almost have been scripted. Just as the speaker raised the problem of people within the West saying ‘Yes it is free speech, but’ to signal the limits of their support, the murderer added his own full stop to the debate from outside by opening up with an M95 assault rifle, leaving Finn Noergaard, a Danish film-maker, dead. (The gunman later killed another man in an attack on a synagogue in the city.)

There is no equivalence, of course, between bullets and buts, between violent assaults on free speech and equivocal endorsements of it. Might it be, however, that the weakening of support for free speech in the West, signalled by the rising chorus of ‘buts’ attached to it, has encouraged those few willing to take more forceful action to put a stop to what they deem offensive?

Two crimes were committed against the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January 2015.

Islamist gunmen committed mass murder at the paper’s Paris offices. They shot dead eight cartoonists and journalists, two police officers and two others, in a graphic demonstration of their hatred for freedom of speech and of the press.

Then the great and the good of Western society committed a mass free-speech fraud. They sold us the line that they all supported free speech, making rhetorical and ritualistic gestures of support for the Charlie Hebdo victims. Yet at the same time many were acting out their contempt for the real freedom of expression that allows such provocative publications to exist in the first place.

The massive ‘Je Suis Charlie’ demonstrations in Paris and many other cities, which followed the massacre and the connected murders at a Jewish supermarket, were uplifting displays of human solidarity that made an impression on us all. They also, however, gave a misleading impression of the state of play with free speech in Europe and America.

Here, it might have appeared, was a clear cultural divide: on one side, a free world united in support of Charlie Hebdo and freedom of expression; on the other, a handful of extremists opposed to liberty and ‘all that we hold dear’. Behind those solidarity banners, however, Western opinion was far less solidly for free speech. Many public figures could hardly wait to stop paying lip service to liberty and start adding the inevitable qualifications, obfuscations and, above all, ‘Buts …’

Those who took a dim view of genuinely free speech in the aftermath of Charlie Hebdo were not confined to Islamist terror cells. It quickly emerged that the threat to freedom came not just from a few barbarians at the gate. Free speech faces more powerful enemies within the supposed citadel of civilisation itself.

The moving displays of solidarity were primarily showing sympathy with the murder victims. Support for freedom of speech as embodied by the consistently offensive Charlie Hebdo was a lot less solid. It might have been more appropriate if many of those placards had named individual victims – ‘Je Suis Charb/Wolinski/Elsa’ – rather than Charlie the magazine. From the Guardian to Sky News, media outlets in the UK which expressed outrage at the murders still felt obliged to apologise for any offence caused by allowing a glimpse of the post-massacre cover of Charlie Hebdo, with its cartoon image of Muhammad.

Even before the dead had been buried, it turned out that the ‘worldwide’ support for Charlie Hebdo’s right to free speech was far from universal – and that those of a different persuasion were not confined to the hostile parts of the Islamic world.

An international consensus of a different hue quickly emerged, to agree that the Charlie Hebdo massacre showed the need to apply limits to free speech and restrict the right to be offensive. This consensus included some unusual bedfellows, notably His Holiness Pope Francis and the Communist Party of China.

Soon after condemning the murders, the Pope almost appeared to suggest that those cartoonists he called ‘provocateurs’ had been asking for it. His Holiness declared that ‘There is a limit’ to free speech, that ‘You cannot insult the faith of others. You cannot make fun of the faith of others’, and that it was ‘normal’ for those who do so to ‘expect a punch’.2

The state-run Xinhua News Agency, official voice of the Chinese Communist regime, was a couple of days ahead of the Pope in stating that ‘the world is diverse and there should be limits on press freedom’. Its editorial made clear that, for China’s authoritarian rulers, ‘unfettered and unprincipled satire, humiliation and free speech are not acceptable’.3

To which the natural response might be: ‘Is the Pope a Catholic?’ and ‘Do Red bears dump on the press?’ Nobody should have been too shocked to hear such views on punishing heretics from the head of the Church whose Inquisition condemned Galileo, or from the Chinese state hierarchy that has kept its press on the shortest leash and freedom in a noose.

More surprising was that the joint Vatican–Beijing statement setting ‘limits’ to what the likes of Charlie ought to say seemed to become the accepted party line for many in the supposedly liberal-minded West, who also want to rein in ‘unfettered satire and free speech’. No sooner had they got the niceties of paying respects to the dead out of the way than they embarked on wholesale free-speech fraud.

There were loud accusations of hypocrisy after the appearance of autocratic governments from the Middle East and Africa at the Paris ‘Je Suis Charlie’ demo. As one US professor at George Washington University tweeted, ‘Glad so many world leaders could take time off jailing and torturing journalists and dissidents to march for free expression in France.’4

Yet double standards flourished much closer to home.

The French authorities led the way, responding to the murderous assault on free speech in their capital by ordering a crackdown – on those whose speech they found offensive. The Justice Ministry sent a letter to all French prosecutors and judges ‘urging more aggressive tactics’ against suspected hate speech and those accused of defending terrorism. A week after the Charlie Hebdo attack, more than fifty people had been arrested for speech crimes.

Among those scooped up was the notorious anti-Semitic comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala, arrested as an alleged ‘apologist for terrorism’ after he posted on Facebook that: ‘Tonight, as far as I’m concerned, I feel like Charlie Coulibaly’ – a fusion of ‘Je Suis Charlie’ with the name of the assassin in the kosher supermarket, Amedy Coulibaly. Whether you consider that an ironic joke or an attempted justification for violence, it was only words – and only one word, ‘Coulibaly’, made it controversial. Yet that word could have cost Dieudonné up to seven years in prison. In fact he was convicted of ‘condoning terrorism’ and given a two-month suspended jail sentence. The French authorities thus spelled out their version of standing up for free speech: they would fight to the last for the people’s right to say things that government and judges approved of.

Across the Channel, the free-speech fraudsters turned out in force in the UK. Some overcooked their disdain for Charlie Hebdo: the European editor of the Financial Times sparked a backlash by writing a column which accused the ‘stupid’ satirical rag of ‘editorial foolishness’.5 In an apparently irony-free move, the Financial Times then felt obliged to ‘update’ (meaning censor) his column for paying too little heed to Charlie Hebdo’s right to freedom of expression.

At least he was trying to be honest about it. If anything, it was more objectionable to witness the display of double standards from UK politicians and liberals who have led the campaigns to criminalise ‘offensive’ speech and sanitise the scurrilous, dirt-digging British tabloid press in recent years, yet now expected us to believe that they are freedom fighters for the satirical and scandal-mongering French press’s right to offend.

Straight after Charlie Hebdo, Conservative prime minister David Cameron told parliament that ‘we stand squarely for free speech and democracy’. In later interviews Cameron even said that ‘in a free society there is a right to cause offence’. This was the same UK prime minister whose government was presiding over a state where people were being arrested and jailed for posting unpleasant jokes and messages online or singing naughty songs at football grounds, and whose justice secretary had just pledged to quadruple prison sentences for offensive internet ‘trolls’ found guilty of speech crimes.

Cameron also insisted after Charlie Hebdo that as a politician ‘my job is not to tell newspapers and magazines what to publish or what not to publish’. That would be the same prime minister who in July 2011 set up, with the support of all party leaders, the Leveson Inquiry not merely to probe the phone-hacking scandal but to cleanse the entire ‘culture, ethics and practices’ of the offensive UK tabloid press and propose a new system to tame it. On that occasion Cameron had a very different message for parliament about what he could tell the press to do, asserting that: ‘It is vital that a free press can tell truth to power … it is equally important that those in power can tell truth to the press.’6 One can imagine what the increasingly offence-sensitive British authorities would have said to any Charlie-type magazine whose front covers had dared to mock Muhammad in the UK.

On the day of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, Labour Party leader Ed Miliband stood with prime minister Cameron in the House of Commons and vowed to resist all attacks on ‘our democratic way of life and freedom of speech’. Away from the cameras, Miliband’s Labour team was busy finalising plans to create an official ‘blacklist’ of those convicted of speech offences online that would warn prospective employers not to hire them – the sort of thought-policing measure some might think has more in common with McCarthyism and witch-hunts than democracy and freedom.7

A month after parliament had united in support of Charlie, an all-party committee of UK MPs went further still down that slippery slope and called for persistent online ‘hate speech’ offenders to be issued with ‘internet ASBOs [Anti-Social Behaviour Orders]’ that would ban them from Facebook and Twitter, a punishment currently reserved for convicted sex offenders. It is not too hard to imagine the name of the allegedly racist, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, sexist and homophobic Charlie Hebdo being among those nominated for any such state hit-list of ‘haters’ to be denied free speech.8

And let us not leave out Harriet Harman, deputy Labour leader and the party’s self-styled champion of press freedom. In a statement after the Paris murders Harman expressed her concern that ‘this crime will cause a chilling effect and undermine free speech’. She declared that ‘free speech is a basic human right for every individual and no democracy can function without freedom of the press’, that the ‘right to satirise, to lampoon and to criticise is a freedom which we must celebrate and defend’, and pledged ‘to take all the steps necessary to assure our journalists and media that we will do everything we can to defend that right of free speech’.9 Strong and admirable words. A few weeks later, however, Harman was back to using slightly less freedom-loving words when she appeared at a Hacked Off rally in Westminster to warn those same journalists and the media that Labour was ‘absolutely committed’ to implementing Lord Justice Leveson’s proposals for state-back regulation of the UK press and that, if elected, a Labour government would ‘follow through on Leveson’ with laws to bring a free press to heel. As well as Harman’s promise/threat, that rally featured former funnyman John Cleese of Monty Python fame comparing journalists opposed to state-backed regulation to murderers, who would also ‘like to regulate themselves’. ‘The murderers would make a very good case,’ said Cleese. ‘They’d say we murdered a lot of people, we know people who have murdered people. We really are best qualified to regulate …’ No doubt the surviving satirical journalists at Charlie Hebdo would have found the comparison hilarious.10

Alongside the political campaign to tame the UK press, the police and prosecutors have been conducting their own war on the tabloids. British police chiefs stood outside Scotland Yard in solidarity with the officers and journalists killed in Paris. Meanwhile, back in the real world, the Metropolitan Police had arrested more than sixty tabloid journalists in what amounts to a three-year witch-hunt.

Much of the cultural elite in the UK wrestled with its liberal conscience in response to Charlie Hebdo, and lost. The novelist Will Self wrote that the murderers were ‘evil’ (while insisting that we all share their ‘murderous, animal instincts’). Yet Self could not stop himself also complaining about how ‘our society makes a fetish of “the right to free speech” without ever questioning what sort of responsibilities are implied by this right’, as if there was something perverse about extending ‘free speech’ to irresponsible cartoonists.11 Higher still in the literary stratosphere, the London Review of Books, a self-proclaimed champion of artistic expression, could barely disguise its lack of empathy with the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists. A ‘deeply disappointed’ reader wrote to ask why the journal had issued ‘No message of solidarity, no support for freedom of expression’ in the aftermath of ‘the execution of the editorial staff of a magazine a few hours’ journey from your own office’. LRB editor Mary-Kay Wilmers published a curt response stating that ‘I believe in the right not to be killed for something I say, but I don’t believe I have a right to insult whomever I please.’ Perhaps the LRB thinks those whose insults go too far should be punished, but that the sentence was excessive. Wilmers dismissed those ‘who insist that the only acceptable response to the events in Paris is to stand up for “freedom of expression”’. As with Self, those tell-tale inverted commas appeared to offer the same comforting support to ‘freedom of expression’ as a noose might to a hanging man.12

Even in the USA, land of the free and home of the First Amendment that gives constitutional protection to freedom of speech and of the press, the free-speech fraudsters were quick to distance themselves from Charlie Hebdo. President Barack Obama and secretary of state John Kerry both made bold statements in defence of free speech, Kerry winning plaudits for insisting that ‘no matter what your feelings were about [Charlie Hebdo], the freedom of expression that it represented is not able to be killed by this kind of act of terror’.13 The Obama administration was then criticised for failing to send any senior representative to the Paris march. However Laurent Léger, an investigative reporter at Charlie Hebdo and survivor of the attack, thought that was a more honest expression of the White House’s true attitude to free speech. ‘You have to be very happy he [Obama] didn’t come to the march in Paris,’ said Léger. ‘[His administration’s actions are] an absolute scandal.’14

Elsewhere in the US at one end of a Charlie-kicking consensus stood Bill Donohue, president of the Catholic League, a group that claims it is ‘motivated by the letter and spirit of the First Amendment’ in standing up for the right of Roman Catholics to speak their minds, regardless of what anybody else might think. Yet Donohue quickly dismissed the free-speech rights of the French cartoonists, asserting that ‘Muslims are right to be angry’ at the ‘insulting’ depictions of their prophet. He conceded that killing should not be tolerated before adding the punchline ‘but neither should we tolerate the kind of intolerance that provoked this violent reaction’, and concluded by criticising the editor of Charlie Hebdo for failing to understand ‘the role he played in his tragic death’. Clearly the spirit of the First Amendment would not be visiting atheist cartoonists.15

At the other end of the US consensus stood a clique of influential liberal and radical bloggers and tweeters, all seemingly keen to assure us that ‘these killings have nothing to do with freedom of speech or expression, regardless of how much our rulers and France’s try to cast them that way’.16 Kitty Stryker, self-styled ‘Geeky Porn Starlet/Lecturer/Presenter/Sex Critical Feminist’, summed it up for many. Although she is ‘generally pretty anti-censorship’ and ‘a big fan of art, and using humour to hopefully make people think and change their minds’, Kitty the feminist fighter draws the line at the likes of Charlie Hebdo, since ‘I do not believe that racist, homophobic language is satire’ (like other critics, she felt no need to explain how Charlie Hebdo had managed to be racist). Then she gets to the point: ‘I don’t think that shooting up the Charlie Hebdo offices was ethically Right with a capital R, OK? BUT I do think it’s understandable.’17 So to satirise Islam is unacceptable, but mass murder of satirists is understandable. And it has nothing to do with any attack on freedom of expression. Got that? Or are you a racist too?

One illustration of how far the tide might be turning against free speech in the US came when the departing ombudsman of National Public Radio declared ‘I am not Charlie’. In his ‘farewell blog posting’ Edward Schumacher-Matos wrote: ‘I do not know if American courts would find much of what Charlie Hebdo does to be hate speech unprotected by the Constitution but I know – hope? – that most Americans would.’18 What Schumacher-Matos seemingly ‘does not know’ is that there is no such thing as ‘hate speech unprotected by the Constitution’; offensive ‘hate speech’ is protected in the US by the First Amendment, as Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons certainly would be. Yet a leading media figure, who has not only worked as a journalist on top American newspapers for more than thirty years but even lectures on the First Amendment as a visiting professor at the prestigious Columbia University School of Journalism, apparently thinks otherwise, believing that Charlie Hebdo could – and should – be legally thrown to the wolves.

Surveying the different strands of this discussion in America, the headline on Anthony L. Fisher’s blog for Reason magazine captured the essential message of the free-speech frauds: ‘I’m all for free speech and murder is wrong. But …’19 Of course, everybody with a shred of humanity condemned the cold-blooded mass murder by Islamist gunmen. Well done. They had far less to say about the right of Charlie Hebdo or any other section of the Western press to publish whatever it believes to be true or just funny, regardless of whether it upsets Muslims or Catholics, Tories, socialists or transgender activists.

Asked what he thought of the rhetorical sympathy from the normally hostile European and international establishment, one surviving Charlie Hebdo cartoonist, 73-year old Bernard Holtrop, responded: ‘We puke on all these people who suddenly say they’re our friends.’ In the context that might seem harsh, but fair.20

The free-speech fraud around the Paris killings did not come out of the blue. It would be pleasant to imagine that the vocal ‘Je Suis Charlie’ reaction reflected the strength of support for freedom of speech and of the press in Europe and America. It would also be wrong. If there really was such solid support for free speech, it would not have taken the cold-blooded murder of cartoonists and journalists to prompt our politicians and public figures to mention it. The loud expressions of support for free speech have been so striking because they contrast with the everyday silence on the subject.

In normal circumstances we in the West now spend far more time discussing how to restrict and outlaw types of speech than how to defend and extend that precious liberty. Almost everybody in public life pays lip service to the principle of free speech. Scratch the surface, however, and in practice most will add the inevitable ‘But …’ to button that lip and put a limit on liberty. The ‘buts’ were out in force on both sides of the Atlantic and across the internet after Charlie Hebdo; to quote the American writer Andrew Klavan, it looked like ‘The Attack of the But-Heads’.21

This was the culmination of a steady loss of faith in freedom of speech and the ability of people to handle uncomfortable words or images. In recent years it has become fashionable not only to declare yourself offended by what somebody else says, but to use the ‘offence card’ to trump free speech and demand that they be prevented from saying it.

Charlie Hebdo itself was in the firing line of the war on offensive speech long before the gunmen burst into its editorial meeting. In 2007 the magazine was dragged into court under France’s proscriptive laws against ‘hate speech’ for publishing cartoons of Muhammad, in a case brought by the Paris Grand Mosque and the Union of French Islamic Organisations, with the undeclared support of some in high places. ‘This is not a trial against freedom of expression or against secularism’ was the free-speech fraudster’s protest from the Mosque’s lawyer, Francis Szpiner – who also happened to be a close ally of France’s President Jacques Chirac.22

Charlie Hebdo won that particular case, but others embraced the underlying principle of Europe’s hate-speech laws – that words and images which offend can be a suitable case for punishment – and expressed it in more forceful terms. In 2011 the satirical magazine’s offices were firebombed. There were no mass ‘Je Suis Charlie’ protests on that occasion. Indeed back then some observers were keen to spell out their contempt for Charlie’s right to offend. Time magazine asked whether the firebombed weekly was ‘a victim of Islamists or its own obnoxious Islamophobia?’ For Time’s France correspondent, Charlie Hebdo’s ‘Islamophobic antics … openly beg for the very violent responses from extremists’ that they had received. This voice of liberal America in Europe apparently believed that offensive cartoons were not merely asking for it, but ‘openly begging’ for it. Presumably they got what they’d been begging for in January 2015.23

This culture of offence-taking censoriousness emanates powerfully from Anglo-American universities, traditional bastions of open-minded inquiry and debate. It came as no surprise, after the Paris massacre, to hear a leading student official at Bristol University in England suggest that Charlie Hebdo would have been banned from their campus anyway, since its potentially offensive images would certainly have contradicted the university’s cocooning ‘safe-space’ policies, which treat adult students like delicate flowers and words and images as if they were automatic weapons. What price such a caustic magazine surviving at all in the UK today, where it is apparently considered suspicious even to read Charlie Hebdo, never mind write for it? Several police forces in England reportedly quizzed local newsagents about the names of those who ordered copies of the post-massacre edition.24

Perhaps we need to face the hard fact that the Islamic gunmen who attacked the offices of Charlie Hebdo acted not just as the soldiers of an oldish Eastern religion but also as the armed extremist wing of a thoroughly modern Western creed. The West today is dogged by a creeping culture of conformism. From the official censors of the police and political elite to the army of unofficial censors online, the cri de coeur of these crusaders against offensive speech is You-Can’t-Say-That. The Islamist gunmen took that attitude to a murderous extreme.

A month later came the Copenhagen shootings, when a gunman attacked a café meeting called to discuss issues of free speech and blasphemy, and then a synagogue, leaving two dead. This too sounded like a repercussion of a familiar attitude. The idea of assailing meetings to prevent speakers even being heard has grown more and more popular in radical Western circles in recent years, especially on campus. The reactionary No Platform policy has evolved from one aimed at fascists and political extremists into a broader demand to ban anybody who might cause offence to somebody, from comedians to philosophical societies. Where No Platform protesters seek pre-emptively to shout down or shut down speakers they find offensive, the Copenhagen gunman sought to shoot them down. That is an important tactical difference. But the underlying attitude of intolerance of offensive speech seems familiar. Where do these gunmen get their ideas from? They might be inspired by Western-hating clerics. But they can only be encouraged by a Western culture that seems to have fallen out of love with its own core value of free speech.

The prevailing mood of intellectual intolerance in the upper echelons of Western culture is exemplified by the onward march of Trigger Warnings, from which this book takes its title. The habit of putting a Trigger Warning (or ‘TW’) at the start of any piece of writing or video, to warn readers or viewers of potentially upsetting or offensive content, has spread from US campuses across the Atlantic and the internet. The implied message of a Trigger Warning is that it would probably be better if you did not read or see this. Those delivering a different kind of Trigger Warning in Paris and Copenhagen aimed to cut out the middleman and stop anybody reading the blasphemous Charlie Hebdo or listening to a debate about free speech and blasphemy.

That Copenhagen meeting on free speech and blasphemy was called on the anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini issuing a fatwa condemning the author Salman Rushdie to death for his novel The Satanic Verses, first published in 1988. Rushdie’s was one of few prominent voices raised against the attack of the but-heads after Charlie Hebdo. The author told an audience at the University of Vermont in Burlington that: ‘The moment somebody says “Yes I believe in free speech, but” – I stop listening.’ Rushdie ridiculed the free-speech frauds’ familiar cop-outs that: ‘I believe in free speech, but people should behave themselves … I believe in free speech, but we shouldn’t upset anybody … I believe in free speech, but let’s not go too far.’ The ‘buts’ that began to be heard in the UK and US when Rushdie was accused of going too far and upsetting people twenty-five years ago have since become a deafening chorus. If he stops listening the moment somebody uses any of those weasel formulations these days, Rushdie must spend a considerable amount of time with his smartphone earbuds plugged in.25

That bitter controversy surrounding Muslim protests against The Satanic Verses a quarter of a century ago marked a turning point in attitudes towards offensive speech, when many in the West condemned the fatwa yet chided Rushdie for being too offensive to Islam. It was during that row in 1989 that I first wrote about the importance of the Right to Be Offensive. Then in 1994, as the editor of Living Marxism magazine, I published a declaration in defence of that right. It upheld two principles – ‘No censorship – bans are for bigots and Big Brother’, and ‘No taboos – taboos are for the superstitious and the stupid’ – and an imperative that has informed my attitude ever since: ‘Question everything – Ban nothing’.26

In the two decades since, as the You-Can’t-Say-That culture has advanced, the fear of offending Islam has grown in the West. There has been a sustained effort to bury the issue post-Rushdie, to avoid discussing sensitive or difficult questions about what our society stands for and what unites or divides us. The result has been to suppress free speech and censor what is deemed potentially offensive. As the author Kenan Malik puts it in From Fatwa to Jihad, in recent years the liberal elite ‘internalised the fatwa’. There is now a quite lengthy list of plays, books and exhibitions that have been cancelled or cut in Europe and the US in order to avoid controversy or offence (and not just to Muslims) – often in acts of pre-emptive self-censorship without the need for protests beforehand.27

Having done their best to bury these issues and stymie debate for decades, our elites seem shocked when the tensions suddenly break through the surface of society and explode into view, as in the violent protests against the Danish Muhammad cartoons in 2011, and the murderous assault on the offices of Charlie Hebdo and the Copenhagen debate in 2015.

They then try to force the genie back into the bottle, cracking down on anything deemed to be ‘extremist’ speech. This has led to bizarre cases such as that of Samina Malik, the UK’s ‘lyrical terrorist’, who was given a nine-month suspended prison sentence in 2007 (subsequently quashed on appeal) for writing doggerel in praise of Osama bin Laden. Sample: ‘Kafirs your time will come soon/And no-one will be able to save you from your doom’. You get the idea. For penning this McGonagall-lite on the back of till receipts from the WH Smith store where she worked at Heathrow Airport, Malik was convicted of possessing material that might ‘prove useful to terrorists’ (it is hard to see how). As the lyrical terrorist herself had to point out to the learned court: ‘To partake in something and to write about something are two different things.’ No longer, it seems. She was convicted of a modern British thought crime.28

Not all exponents of radical Islamist doctrine and alleged apologists for terrorism are such harmless scribblers, of course. There are some far more dangerous Islamist demagogues around in the West, accused of effectively acting as recruiting sergeants for al-Qaeda or the Islamic State. In the aftermath of Charlie Hebdo it might be tempting to imagine going along with government attempts to crack down on ‘radicalisation’ and censor extremists in our universities. Wouldn’t it be good if we could simply gag them with the UK’s 2015 Counter-Terrorism and Security Act, and kick them off campus, if not out of the country, altogether?

But such simple authoritarian solutions won’t work. Trying to defend freedom by banning its enemies, to uphold our belief in free speech by censoring those who disagree, would be both wrong in principle and useless in practice. What we need to do is to fight them on the intellectual and political beaches, not try to bury the issues in the sand. The big problem Western society faces is not how to stop radical Islamists expounding their beliefs; it is how best to make a compelling case for what ‘we’ are supposed to believe in. As ever in times of trouble, the only thing that is likely to work is encouraging more speech rather than ordering there be less of it. Free speech is the potential solution, not the problem.

Despite the initial upsurge of ‘Je Suis Charlie’ sentiments, the Paris massacre has not led to any major new campaign for free speech. Quite the opposite – it has reinforced the fear, reticence and confusion surrounding freedom of expression in the West today. This book aims to put the case for unfettered free speech and the right to be offensive. These are both non-negotiable principles and practical necessities to address the problems we face.

That must involve defending the right of a magazine like Charlie Hebdo to offend who it chooses, without any buts, and whether we like it or not. The truth is you don’t have to be Charlie, read Charlie or chortle at Charlie in order to defend it. Free speech is always primarily about defending what a US Supreme Court justice once famously described as ‘freedom for the thought that we hate’.

In passing we might note that wholeheartedly defending Charlie Hebdo’s right to offend need not necessarily mean reprinting its cartoons, as some insisted it must. Freedom of speech and of the press mean that media outlets must be free to make their own editorial judgements about what they publish – just as others must be free to pass judgement on those decisions.

In the free-speech fraud that followed the Charlie Hebdo massacre, many suddenly started talking about the ‘right to offend’ and the fact that there is ‘no right not to be offended’. Quite so. What most of them appeared to mean, however, is that we must defend the right to offend Islamist extremists. Yet the right to be offensive has to be about much more than Islam. It means the right to question, criticise or ridicule any belief or religion – and the freedom of the religious or anybody else to offend secular sensibilities, too.

In the aftermath of Charlie Hebdo Clare Short, a 34-year-old Catholic mother of three and blogger, wrote of her concerns that a fearful backlash against ‘offensive’ speech might now make it hard for her ‘to express my views without fear of prosecution’. She observed that she had ‘never thought I would be appreciating the “right to offend”, but today it seems I am’. Short concluded that ‘Je Suis Charlie, and I would like to proclaim that Jesus Christ is lord, marriage can only occur between one man and one woman, and that abortion is murder. Or am I not allowed to say that?’ If ‘Je Suis Charlie’ is to mean something more than a slogan on a discarded placard, she surely should be allowed to proclaim her beliefs, however out of step with the times they might seem.29

Any such tolerance of traditional opinion seemed seriously out of vogue just two months after the Paris attacks, however, when Sir Elton John led an international celebrity boycott of Dolce & Gabbana, after the two gay Catholic Italian fashion designers told an interviewer they believed gay adoption of ‘synthetic’ babies to be unnatural. The #BoycottDolceGabbana tag swept across social media as many thousands backed the celebs’ demand to close the designers down, not for exploiting workers, overcharging customers or anything else they might have done, but merely for expressing an unfashionable opinion. ‘Elton John is a Taliban,’ said Italian senator Roberto Formigoni in response to the boycott, ‘and is using with Dolce & Gabbana the same method used by the Taliban against Charlie Hebdo.’ Not quite ‘the same method’ – no gun attacks by gay parents on D&G stores were reported – but perhaps a similar-sounding message.30

Defending the right to be offensive also means recognising that the work of such bold cartoonists, whether one considers it insightful or infantile, is not enough. The right to be offensive means something more than the right to ridicule Islam or any religionists. We should be free to question everything that we are not supposed to question in the suffocating cloud of conformism that hangs over our societies today.

France of course is the land of Voltaire, the eighteenth-century revolutionary writer whose views on tolerance and free speech are famously summarised as: ‘I disapprove of what you say, but I will fight to the death your right to say it.’ By contrast, as this book examines, we are now living in the age of the reverse-Voltaires, whose slogan is ‘I know I will detest what you say, and I will defend to the end of free speech for my right to stop you saying it.’

It would be a fitting tribute to those killed in Paris and Copenhagen if we were to rekindle the spirit of the free-speech fighters of yesteryear for the twenty-first century. ‘Je Suis Charlie’ is not enough – we need to send out the message loud and clear that ‘Nous Sommes Voltaire’.