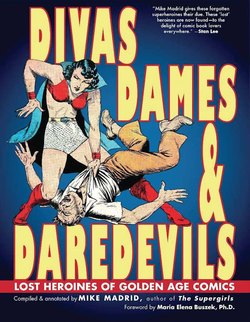

Читать книгу Divas, Dames & Daredevils - Mike Madrid - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление“SHEBAM! POW! BLOP! WIZZ!”

Foreword by Maria Elena Buszek, Ph.D.

In their 1968 duet “Comic Strip,” legendary French singer/songwriter Serge Gainsbourg teamed up with another legend, film vixen Brigitte Bardot, to jump on the Pop Art bandwagon. The sonic equivalent of a Roy Lichtenstein painting come to life, Gainsbourg’s lyrics invite the audience to join him in a comic-book world of word bubbles, adventure, and romance, punctuated by the English-language interjections of Bardot: “SHEBAM! POW! BLOP! WIZZ!” In a video the pair filmed for the song, Bardot is depicted as a comic-book heroine who springs forth from a life-sized painting—an Amazonian queen bursting onto his scene.

Bardot’s superheroine was inspired not only by ‘high’ art’s renewed interest in pop-culture genres like comic books, but by the simultaneous emergence of real-life heroines at what was probably the height of the era’s activism. From the civil rights and anti-colonialist movements to the blossoming women’s and gay liberation groups, women rose to prominence as the most visible—and, often, sexy—symbols of the massive societal changes taking place in the ’60s.

But this upheaval—and these startling superheroines—were not so much a revolution so much as an evolution. Western perspectives on class, race, gender and sexuality have been changing for centuries, through the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. And we of the 21st century are still in the midst of that evolution. In the United States, the cultural shifts brought on by the crises surrounding the Great Depression and World War II got the government involved. First, on a limited scale, there was the equal-rights hiring philosophy of New Deal projects, and then more broadly, as the massive depletion by the war of traditionally-privileged white men found the country in need of all its citizens, no matter how previously marginalized. As President Franklin D. Roosevelt bluntly put it in his 1942 Columbus Day speech: “In some communities employers dislike to hire women. In others they are reluctant to hire Negroes. We can no longer afford to indulge such prejudice.” The country’s military, government offices, and industry responded not only by hiring, but by recruiting women as well—encouraging and even glamorizing roles that for generations had been considered beyond women’s physical and mental capabilities.

Pop culture followed suit. The period’s cinema, music, and pin-ups cherry-picked scrappy models of femininity that had emerged during the Depression, updated in line with new demands being made upon women in the global urgency of WWII. And, as Mike Madrid demonstrates in this rediscovery of the era’s “lost heroines,” comic books also contributed to the cause. In his long-overdue valentine to these forgotten female characters, Madrid has provided us with a look at, and thoughtful contextualization, of the range of women one could expect to find—from Mother Hubbard to Lady Satan, plain Jane (Martin) to Mysta of the Moon—in this golden age of comics.

In keeping with the spirit of the era, most of these little-known heroines justified their extraordinary feats in connection with the war effort: alongside the famous exploits of Amazon-princess-turned-Axis-basher Wonder Woman, Madrid uncovers not just the more humble wartime warrior Pat Patriot, but also ordinary “superheroines” like nurses Jane Martin and Pat Parker, whose extraordinary contributions reflected the real-life heroics of women at war. Indeed, the war seemed to find glamorous women of mystery like Lady Satan and Madame Strange, the supernatural powers of Mother Hubbard and jungle queen Fantomah, and even the ancient Greek goddess Diana all leaping to the Allies’ defense. These fantastic stories were inspired by the real-life drama of the war.

In the same way that real women’s contributions to WWII opened doors in other realms, many of the characters Madrid spotlights demonstrate these gains as well. While the war effort clearly needed nurses and pilots overseas, just as it needed factory workers on the home front, Madrid’s book reminds us that the wartime lack of male workers at home also produced “lady” lawyers, journalists, and investigators—whose exploits fit neatly with the male-dominated conventions of adventure comics—as well as artists, who joined the ranks of male illustrators by producing some of the very work we see in this book. (Unsurprisingly, it was women artists like Barbara Hall, Fran Hopper, and Claire Moe who produced some of the more exciting and unconventional heroines in Divas, Dames & Daredevils.)

Alas, when the war ended the fate of comic-book heroines continued to reflect those of their real-life counterparts. The same country that demanded women question their traditional lot in life during the war soon demanded just as adamantly that it was now their duty to return from the home front to the home. Pop culture reflected this shift by idealizing images of women to fit the culture’s demand for a return to more conventional gender roles. Comics themselves became segregated into “girls’” and “boys’” genres, and it’s telling that almost none of the heroines featured in this book survived to the 1950s. The result of this shift, as Madrid laments, was the start of a decades-long “era where comic book heroines had to be little more than pretty.”

But—as the “Comic Strip” with which I began attests—once unleashed, these heroines did not pass so easily into the historical ether. Like the women who inspired them, these strong female comic-book characters gave society a taste of what exciting new roles women might take on when given the opportunity. They also stubbornly remained in the cultural subconscious. While artists like Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol may have looked to the more vapid corners of comic-book romance and children’s illustrations for inspiration, painter Mel Ramos opened the door wider to reintroduce characters discussed by Madrid, like Fantomah and Señorita Rio. For comic book fans like Ramos, these unruly models of femininity from the war years surely stuck in his childhood memory, just as they no doubt rematerialized as young women in his midst began to more closely resemble these golden-age heroines as the 1960s wore on. It’s no accident that the first issue of Ms. Magazine, published in July 1972, featured Wonder Woman (in a cover illustration by DC Comics artist Murphy Anderson) as symbolic of both the history that the era’s women’s liberation movement sought to honor, and the power the movement felt in its rediscovery.

That Wonder Woman has reappeared on many occasions on the cover of Ms. (most recently, on its 40th anniversary issue in the Fall of 2012) is a testament to the fact—if I may flesh out Madrid’s concluding analysis of these Divas, Dames & Daredevils—that these characters are worth revisiting to see how women lived in the golden age of comics. And more than that—to remind us how far women today still need to go.

* * *

Maria Elena Buszek, Ph.D., an Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Colorado Denver, is the author of Pin-Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture. Her writing has appeared in Bust magazine, Art Journal, Archives of American Art Journal, and TDR: The Journal of Performance Studies.