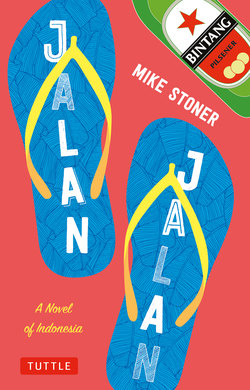

Читать книгу Jalan Jalan: A Novel of Indonesia - Mike Stoner - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINSPECTION

AND APPROVAL

I stand in front of a two-metre-high wall. A camera, mounted next to a large, solid metal gate, is pointed down at me. I check the address against the piece of paper that Pak gave me. It’s the right place. I go the gate and press the intercom, put my mouth next to the speaker and look at the camera.

‘I’m the English teacher.’

The gate slides open just enough to let me through. I enter and nearly do the same as Julie, turn around and walk back out. In front of me is a large Chinese man with some sort of gun slung over his shoulder. I have no idea what sort of a gun, only that it is big and long and it makes my sphincter contract.

Stay calm, New Me. New Me is ‘don’t give a shit’, remember. New Me is after strange and exciting experiences, and this is one. Just smile and walk to the house.

I smile and walk to the house. I say a house, it’s more of a mansion. All the ground-floor windows are shuttered up. There are another three men with similar weapons hanging off their shoulders, playing cards on the bonnet of a shining black Range Rover. Another armed man is walking around the side of the house looking up at the top of the wall as he goes. In front of the house is a large wired enclosure with three Alsatians imprisoned in it. They attack the mesh with teeth and slobber as soon as I pass. I step away to the right.

Stay calm. These things don’t worry you. Nothing worries you. OK?

Got it. Nothing worries me.

One of the guards opens the polished solid-wood front door and shows me in. Once I’m in he goes back out, closing the door behind him. I stay where I am and take in the room before me. The house is all open plan and marble-tiled floors. Straight ahead is the kitchen area. Three Asian women with Jackie Onassis hairstyles, dressed in ‘60s miniskirts and breast-hugging roll-neck tops, are preparing ornate plates of food. Next to the kitchen area is a table which could seat sixteen at a sit-down meal, but which is now covered with a buffet of dishes I can’t make out from here by the door. The smell of garlic and chicken and saffron and a dozen herbs whose names I’ve never known fills the air.

On the opposite side of the room, four near-middle-aged Chinese men sit in front of a large TV screen watching Manchester United, maybe, versus a team in blue. On the coffee table between the men is a pile of money. As I watch, one of the men throws another five notes onto the pile. He yells something at a blond player on the screen, who from here looks like the ever-present Mr Beckham.

At the end of the room there is no internal wall, just three wide marble steps up into an outside area. Reflections and light ripples dance on the far outside wall, telling me there is probably a pool just up those steps.

‘Ah, the new teacher.’ This is one of the men at the TV. ‘Fitri, Benny,’ he shouts, ‘your new teacher is here.’

He comes over to me, but keeps an eye over his shoulder at the football.

‘Good to meet you. I am Charles.’ He offers me his hand and takes his eyes away from the game to inspect me. He doesn’t let go of my hand, but instead holds it tight while he looks deep into my eyes. Unblinking dark, narrow eyes search mine as though he’s trying to find something. The intensity hurts. I try not to blink as some sort of defiance to his ocular rape of me, but don’t manage it. The intimate examination lasts only two or three seconds, but I haven’t been breathing. As he lets go of my hand I suck in air.

He is about forty-five, my height, neatly side-combed hair, thin lines around his eyes—probably from all the examinations he carries out—and despite his red and white Hawaiian shirt, no sense of humour about him whatsoever.

‘Come.’ He leads me to the buffet and waves his hand over the food. ‘Eat what you want. Drink the wine, it is flown in from France, the cheese too.’ He slices a piece of Brie and takes a bite. ‘The other food is also from Europe and Australia and the States. All good. Please eat what you want.’ He is already walking back to his seat. ‘The children come soon.’

He lowers himself slowly into his chair by the TV, where, sitting upright and regal, he returns his attention to Mr Beckham and friends.

The old adage of there being no such thing as a free lunch troubles me a little, but sod it. I pick up a plate from a pile on the table and cut myself some Stilton, perfectly soft Brie, a slice of crusty white bread, avoid the king prawns, lobster and plates of ham, beef and chicken, take a spoonful of mixed salad and another of garlic mushrooms, a slice of some sort of white fish and then pour from a bottle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape into a crystal wine glass. The lesson is going to be worth doing for the food alone.

I stand with the plate in one hand and the wine in the other and am wondering what to do next when a teenage girl and young boy come out of a door near the gamblers. They come straight over to me.

‘I am Fitri,’ says the girl, about fifteen and about to become beautiful.

‘I am Benny,’ says the boy, about ten and about to become chubbier as he grabs a plate and piles on most of the beef and five tiger prawns.

Their father says something to them in Chinese without looking away from the TV.

‘My father says we should go to the games room. Please, this way,’ says Fitri as she leads me and little brother towards the steps. At the top of the steps I swig a large mouthful of wine as I take in the pool, which is half covered by a roof and half open to the blue sky. It’s about twenty-five metres in length and surrounded by the rest of the building. There are five doors which go off from it into other parts of the house.

‘Bring your shorts next time,’ says Fitri, going on ahead down one side of the pool, ‘we can swim.’

Benny sucks the internal workings of a prawn into his mouth.

I follow them through a door at the far end of the pool and enter a large games room containing a full-size snooker table, dartboard, ping-pong table and jukebox. In the corner is a pile of beanbags, which is where Fitri leads us. She slumps onto one, Benny falls backwards into another, losing his remaining prawns over his shoulder. He picks them up off the floor and puts two onto his plate and one into his mouth. Fitri slaps him across the head.

‘My brother is a pig.’

‘My sister is a bitch.’

I place the wine and plate next to my beanbag and flop into it.

‘First English lesson: bitch is a bad word.’ I wriggle around until I’m stable and then pick up my wine. It tastes better than anything Sainsbury’s back home has to offer.

‘But she called me a pig,’ says Benny, as he pulls the remains of prawn number three from his mouth. He wipes his lips on his arm.

‘Well pig isn’t exactly polite, but sometimes it is suitable for little boys.’ I shove a handful of mushrooms into my mouth. ‘And for grown men.’

Benny laughs, opens his mouth wide, tilts his head back and slowly lowers the last crustacean into the chasm.

‘Oh great,’ says Fitri, ‘two idiot pigs.’ Then she laughs.

‘So,’ I say, ‘I think your English is already very good. Why is that?’

‘My father speaks very good English and he often takes us to Australia and sometimes America,’ Fitri says with a tone of superiority. ‘He goes there on business.’

‘And what is his business?’

‘He owns discos. Also he does import and export.’

‘What does he import and export?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Oh.’

‘He is very important,’ adds Benny.

‘I’m sure. So what should I be teaching you two expert students?’

The wine is very good. My glass is already nearly empty.

‘You are the teacher. What do you think?’ asks Fitri.

‘OK. Why don’t you just ask me questions about anything you want and I’ll try to answer. Any mistakes you make I’ll try to correct and explain.’

They both agree and we start a question-and-answer session.

‘Do you have a girlfriend?’ asks Fitri.

—Good start, says Laura, what are you going to say to that one?

—You’re my girlfriend.

—Oh am I? I thought I’m dead and you were trying to forget me.

—Don’t remind me.

The wine suddenly turns bitter in my stomach.

‘Well?’ interrupts Fitri.

‘Well?’ adds Benny.

‘Yes. No. I used to have.’

‘Was she beautiful?’

‘Very.’

‘Do you miss her?’

‘Very much.’

—Oh, get over me. You know you want to.

—I wish I could.

—What happened to New You? I thought he was supposed to be shot of me.

‘Why did you break?’

‘Break up. The proper way to say it is break up.’ My voice crackles. ‘Why did you break up?’

‘She left me.’ Barely audible.

—Liar. Face the truth. I’m dead, numbnuts.

‘She died.’ I drain the last of the wine from my glass and smile at the two children in front of me. ‘She died,’ I whisper. I swallow. I blink blurriness from my eyes. There is something big and painful ballooning in my chest.

—Well said.

‘That is sad. Are you sad?’ Fitri curls her legs under herself on the beanbag.

‘Yes. Sorry. Where’s the toilet?’

It’s growing and pushing on my lungs. I need it out or I won’t be able to breathe.

‘Outside this room and two doors on the right.’

‘Thank you.’ I push myself up and out of the beanbag and lunge for the door. I am using every muscle in my stomach and chest and face to keep it in. My vision is tunnelled as I focus on door handles and my feet and the pool sparkles beside me and then I’m closing doors and fumbling locks and I turn and sit on the closed toilet and my head is in my hands. It bursts out. Sobs and tears and snot rise up through my throat and nose and eyes. I’m stunned there’s so much in there. I’m like a shaken can of lemonade just opened.

Finally, after I don’t know how long, and with stinging eyes and burning cheeks, it’s all out and I’m empty. I blow my nose, splash water on my face, look at my red eyes in the mirror, try to out-stare myself.

‘Stop it. You’re hidden. You don’t do this. You don’t throw that shit up at me. You don’t remind me or tell me or tease me. I’m not listening. I’m not interested.’

No answer. Good.

I throw another handful of water over my eyes, look at New Me and nod my head.

‘Sorted.’

And this weekend I’m going to get wasted, get stoned, do anything and everything I have to do to get my new self on the road to reckless completion.

I dry my face on a soft, laundered towel that smells of lavender, unlock the door and step out onto the poolside, where Charles is waiting for me with a lit cigarette in one hand and an unlit held out to me in the other.

‘Are you alright?’ he asks. ‘Please.’ He holds the cigarette closer to me.

‘Thank you.’ I take it and he lights it with a solid gold Zippo. ‘I’m fine, thanks.’

‘Fitri told me you didn’t look well and she’s worried she made you unhappy.’

‘It’s OK. It wasn’t her fault.’ I feel his eyes watch every movement of my face. ‘You know, memories jump out at you sometimes.’

‘Yes. I know.’ He drags on his cigarette and the examiner’s eyes soften as he looks down into the light blue of the pool.

‘This is a very nice house,’ I say, not knowing what else to say.

‘Thank you.’ His eyes focus on me again. ‘If you don’t want to keep teaching today, it is no problem. I understand.’

‘No. I can teach. This isn’t a very good first impression. I’m sorry.’ I draw heavily on the cigarette. I read the banner around the filter: Davidoff.

‘Don’t be sorry. Life likes to surprise us at the most inopportune of times.’

‘You have nice children.’ Nice, what a crap word.

‘Thank you. They are a little hard work at times. I worry about them, living here, in a house that looks more like a prison.’

‘Why do you have such security?’

Charles smiles and nods.

‘I am a businessman who sometimes does business that creates enemies. Since the riots I don’t take risks anymore. I don’t trust people.’ He drops his cigarette and kicks it into the pool. I don’t think I will bring my swimming gear next time.

‘Riots?’ I feel I should know what he’s talking about.

‘You don’t know? You English, you are only interested in your royal family and the weather.’ He puts a hand on my elbow and starts leading me back along the pool. ‘It was 1998. Just two years ago. Economic and race riots. It was a very bad time for us Chinese living here. I will not put my family at risk again of these fucking people.’

‘What people?’