Читать книгу The Danube Cycleway Volume 2 - Mike Wells - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The upper and middle Danube from Germany through Austria to Vienna and on to Budapest in Hungary is one of the world’s most popular cycle routes, followed by cyclists of all ages and abilities. (For a description of the route from the Black Forest to Budapest see The Danube Cycleway Volume 1 by the same author.) But the Danube Cycleway does not end at Budapest. It continues for another 1717km at first through Hungary, then the countries of Croatia and Serbia (former Yugoslavia) and Romania, all the way to the Black Sea. The cycleway still follows the river, but the resemblance ends there. Unlike the well-developed tourist infrastructure of Germany and Austria, after Budapest you enter a region where tourism is still in its infancy.

As a result, by cycling the lower Danube you embark upon an adventure where the very journey becomes something of a challenge. Tourist offices, places to stay and cycle shops are few and far between, while West European languages are little spoken. You need to plan accommodation ahead and be more self-sufficient when it comes to maintaining your cycle in working order. The fact that you cross the line of the former Iron Curtain twice, pass through an area that was involved in a violent civil war as recently as 1999 and skirt the edge of the old Soviet Union all add to the sense of adventure. But don’t be discouraged by this. Cycling the lower Danube is well within the capabilities of most cycle tourists. The people are warm and friendly and both road surfaces and waymarking have improved a lot in recent years. This book is intended to help the average cyclist complete this adventure successfully.

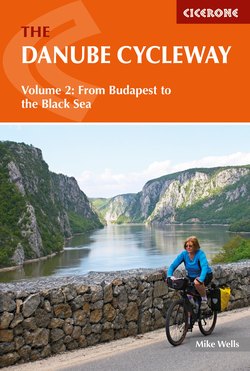

The chain bridge spans the Danube between Buda (left) and Pest (right) (Stage 1)

The 2772km-long Danube is Europe’s second longest river (behind the Volga). Rising in the German Black Forest, it runs through 10 countries on its way to the Black Sea. This guidebook covers the 1647km that the river flows from Budapest to the extensive delta in Romania where it empties into the sea. As the Danube has dropped to an altitude of only 100m above sea level by the time it reaches Budapest, the cycleway following the river is mostly level. Through Hungary and Serbia the route follows long off-road stretches along flood dykes. In Romania cycling is mostly along the Romanian Danube road (Strada Dunarii), a quiet long-distance road set back from the river alongside the flood plain, which was built in the mid-19th century to open up the southern part of the newly unified country.

The route follows part of EuroVelo route 6 (EV6), a trans-continental cycle route running from the Atlantic coast of France to the Black Sea. This is well waymarked in Hungary and Serbia, partly so in Croatia but unmarked in Romania. This guide breaks the route into 32 stages, averaging just under 54km per stage. In theory a fit cyclist covering 90km per day should be able to complete the trip in 19 days. However, this is difficult to achieve because of unequal distances between overnight accommodation, and so, unless you are camping, it is advisable to plan on taking between three and four weeks.

The main sights encountered en route include the great cities of Budapest and Belgrade and the rugged Iron Gates gorges where the Danube has forced its way through a gap between the Carpathian and Balkan mountain ranges. Although the river rushing through the gorge has been tamed by the construction of two huge dams, this is still an awe-inspiring place. The lake behind the dams has flooded Roman Emperor Trajan’s military road that followed the river and a new corniche road has been built which climbs above the gorge with spectacular views. The route ends in the Danube Delta, Europe’s largest area of natural wetland and home to an enormous variety of bird species. Although the cycleable route ends 73km short of the river mouth, it is possible (and recommended) to take a boat through the delta to the zero kilometre point where the Danube enters the Black Sea, a suitable place to conclude your adventure at the very end of Europe.

Background

As the major river of central and south-eastern Europe, the Danube has played significant roles in the history of the continent, first as a border, then as an invasion route and later as an important transport and trade artery.

A Roman frontier

The first civilisation to recognise the importance of the river was the Romans. After pushing north through the Balkans, they arrived on the banks of the lower Danube around 9BC. Seeing the value of a natural and defendable northern border to protect their empire from barbarian tribes, the Romans established fortified settlements along the river from Germany all the way to the Black Sea, the largest of these in the section covered by this guide being Aquincum (near Budapest), Singidunum (Belgrade), Viminacium (near Kostolac) and Durostorum (Silistra). The Romans knew the border area as the Limes and settlements were connected by a series of military roads. The Romans advanced across the Danube (AD101) into Dacia (modern day Romania) but withdrew again in AD271. After the Roman Empire split in two (AD330), the province of Pannonia (modern day Hungary and Croatia) became part of the Western Empire and Moesia (Bulgaria and Serbia) part of the Eastern (later Byzantine) Empire. The Western Roman Empire collapsed and was overrun by barbarians in the fifth century, leaving the Byzantine Empire to soldier on until 1453.

A reconstruction of a section of Trajan’s Roman bridge over the Danube in Drobeta-Turnu Severin (Stage 16)

The Great Migrations

After a period of tribal infighting, a number of nomadic tribes from the Asian Steppes started crossing the Carpathian mountains. In the sixth century, Slavs settled in Serbia, from where they expanded across much of the southern Balkans. The Avars arrived in Romania and Hungary in AD568, while the Bulgars captured Moesia from the Byzantines in AD681, creating the first Bulgarian kingdom. Apart from a brief return to Byzantine rule in 11th–12th centuries, the Bulgars remained in power until overrun by Ottoman Turks in 1396. The Magyars came to the region after AD830, at first trying to dislodge the Bulgars, but when this failed they turned north to take Romania and Hungary from the Avars in AD895.

Árpád, leader of the Magyars, is commemorated in Ráckeve (Stage 1)

Hungary and the Magyars

The Magyars, led by Árpád, settled Hungary between various tribal groups. The conversion to Catholic Christianity in 1000 of King Istvan I (Stephen I), who was canonised as Szent Istvan, and adoption of western European script and methods of government, established the country as a European nation. Over the next 500 years a succession of kings steadily expanded the Greater Hungarian Kingdom and by the beginning of the 16th century in addition to Hungary and Transylvania (northern Romania) it included all of modern day Slovakia, much of Croatia plus parts of Austria, Poland, Serbia and Ukraine. However a peasants’ revolt in 1514 and disputes between the king and his nobles left the country in a weak position between two other powerful empires, the Ottoman Turks and Austrian Habsburgs.

Ottoman Turks

Having captured Bulgaria in 1396 and the Byzantine capital Constantinople (modern day Istanbul) in 1453, the Islamic Ottoman Turks continued to move north. In 1525, as part of long held ambitions to extend their territories across the Balkans into central Europe, they formed an alliance with France aimed at confronting the power of the Habsburg-dominated Holy Roman Empire. After taking Belgrade (1521), then a Hungarian city, the Turks were well placed to march upon the Habsburg capital, Vienna. To do so they first had to conquer Hungary. In 1526 the advancing Turks routed a Hungarian army, commanded by King Ladislaus II, at the Battle of Mohács (Stage 5), and although the King managed to escape he drowned crossing the river. Many Serbs and Hungarians fled before the arrival of the Ottomans who captured Budapest unopposed and went on to lay siege to Vienna in 1529, although they failed to capture it. The death of King Ladislaus, who had no heir, marked the end of the independent Hungarian Kingdom, the crown passing by marriage to the Austrian Habsburgs, who ruled what was left of the country from Pressburg (modern day Bratislava). Southern Serbia was annexed by the Ottomans in 1540.

For nearly 160 years the Turks controlled the lower Danube basins, ruling over a mainly empty land, the Christian population having either fled or been slaughtered. A number of attempts to push further into western Europe were unsuccessful, culminating in defeat at the second siege of Vienna (1683), a battle that was hailed by the Catholic Church as the deciding victory of Christianity over Islam in Europe. The Turks were gradually pushed back through Hungary by Habsburg forces, before being expelled from Hungarian territory after the Battle of Belgrade (1688). They did however retain control of southern Serbia, Wallachia (southern Romania), Dobruja (Danube Delta) and Bulgaria.

The battlefield at Mohács where defeat by the Ottoman Turks ended the Hungarian Kingdom (Stage 6)

The Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg, which originated in 11th-century Switzerland, came to prominence when Rudolf von Habsburg became king of Germany (1273) and Duke of Austria (1282). After becoming the dominant force in the Holy Roman Empire, a series of dynastic marriages expanded Habsburg power over Spain and its American colonies, Burgundy, the Netherlands, Bohemia and much of Italy. Along the Danube they controlled Austria itself, the Austrian Vorland (modern Württemberg) and Slovakia after 1526. When Prince Eugene of Savoy, commanding Habsburg forces, drove the Turks out of Hungary in 1687, Hungary and its territories in Croatia, Vojvodina (northern Serbia) and Transylvania (northern Romania) all came under Habsburg rule. The Habsburgs repopulated the empty lands with returning Hungarians and Serbs plus large numbers of Swabian Germans who had been displaced from Germany by the Thirty Years War. The Danube was the major transport corridor linking this empire together.

Independence movements

In 1848 the Austrians put down a violent uprising, seeking Hungarian independence. However, the Hungarians did gain a measure of self-government under the overall rule of the emperor, with the Habsburg possessions being rechristened in 1867 as the Austro-Hungarian Empire. At the same time there were unsuccessful uprisings by the Serbs in Novi Sad against their Austrian rulers and by Romanians in Wallachia against Ottoman rule. Although these were put down by a combination of Russian and Turkish forces, they started a process by which Wallachia and Moldavia gained independence (as Romania) from Turkey during the Russo-Turkish war of 1877–1878. This same war also saw Bulgaria and Serbia escape from Turkish rule and represented the beginning of Russian interest and influence in the region.

The First World War and its consequences

The shots that started the First World War (1914–1918) occurred in Sarajevo (Bosnia) when a Serb nationalist assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. Austria retaliated by attacking Serbia, starting a snowball effect in which a series of alliances drew almost all of the nations of Europe into the conflict.

From Zemun (foreground) the first shots of the First World War were fired at Belgrade (far distance) across the River Sava (Stage 11)

The Treaties of Versailles (with Germany), St Germain (with Austria), Trianon (with Hungary) and Sevres (with Turkey), which followed the war in 1919–1920, had an enormous effect on both the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Turkish empires. The Habsburgs lost their throne after over 600 years and their empire was dismantled with Romania gaining Transylvania and Slovakia becoming part of the new country of Czechoslovakia. Hungary and Austria were left as two small independent nations. In Turkey, the Ottomans were removed and their empire dismantled. The new kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which included Serbia and territories once controlled by both Austro-Hungarians and Ottoman Turks, gained the most. In 1929 it assumed the name of Yugoslavia (literally ‘land of the south Slavs’). There was an extensive movement of peoples, particularly of Hungarians leaving Transylvania and Vojvodina.

In Germany the effect was mostly economic, large reparation payments and inflation leading to national bankruptcy and political unrest. The Nazi party, led by Adolf Hitler, took advantage of this upheaval, taking power in Germany in 1933 with a policy that included overturning Versailles and expanding German territory. A referendum in Austria (1938) led to the Anschluss, political union between Germany and Austria under Nazi control. German invasions of Czechoslovakia and Poland led to the Second World War (1939–1945), with Hungary, seeking to regain territory lost in Trianon, joining the German-Austrian Axis. For a variety of local reasons, Romania, Bulgaria and the Croatian part of Yugoslavia also supported the Axis powers. The Germans invaded Yugoslavia (1941), where they met fierce resistance from communist partisans led by Josip Tito. After the failure of Germany’s attempt to invade Russia (1942), Russian forces slowly got the upper hand and pushed German forces and their allies back through central and south-eastern Europe.

Iron curtain and communism

Defeat of the Axis powers in the Second World War led to the lower Danube coming under the control of the victorious Allied powers, specifically Soviet Russia. Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania were all forced to adopt communist systems of government with private property expropriated by the state and farms collectivised. Their economies and military capabilities were integrated with that of the Soviet Union under the terms of the Warsaw Pact. The economic and social consequences of this period are still very much in evidence, particularly in Romania. Large estates of poor quality social housing ring most towns and cities, while dilapidated ruins of Soviet era factories abound. The border between Soviet controlled eastern Europe and western Europe was heavily fortified by the Russians with a line of defences described by Winston Churchill as an Iron Curtain. An uprising against communism in Hungary (1956) was viciously put down by Russian troops.

Yugoslavia, now led by Tito, adopted a less rigid communist system and did so without coming under Russian control.

The 1956 uprising against communism is commemorated by a monument in Budapest (Stage 1)

Yugoslav Civil War

Ever since its creation in 1919, Yugoslavia was always a disparate country. Actions to create a unified nation, such as the adoption of a common language (Serbo-Croat) and integration of ethnic groups were only partially successful. Tensions between Muslim Bosnians, Catholic Croats and Orthodox Serbs were kept in check during the rule of Tito, but after his death in 1980, the country began to disintegrate. After Slovenia and Croatia seceded from the Yugoslav Federation in 1991, all out civil war started, with the Serb dominated Jugoslav National Army (JNA) being used in an attempt to stop the secession movement. Fighting was particularly intense along the Danube border between Croatia and Serbia, especially around Vukovar (Stage 7). Later the conflict spread to Bosnia and in all these regions military action was accompanied by atrocities against minority civilian populations. Leaders in all three countries have since been arraigned for war crimes.

Most fighting ceased in 1995, but a final twist to the war came in 1998–1999 when Serb forces tried to prevent Kosovo from seceding. This resulted in reprisal bombing of Serbia by NATO air power. Altogether it is estimated that 140,000 people died during the conflict, while a further four million were displaced as refugees, many permanently. Although the war is over, with former Yugoslavia broken-up into seven independent states, tensions still exist between Croat and Serb communities, with damage much in evidence and unexploded ordinance in conflict areas. However, there is no need to be worried as far as this journey is concerned. It follows a safe route through what was the front line between Serbia and Croatia.

Vukovar war cemetery is the site of a mass grave of Croat victims of the Yugoslav Civil War, marked with 938 crosses (Stage 8)

European Union

Following the collapse of communism in 1989, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria were quick in seeking new alliances within Europe. They all joined NATO and between 2004 and 2007 became members of the European Union. Croatia joined the EU in 2013 after difficulties had been settled arising out of the Yugoslav Civil War. Serbia has an application to join the EU pending, while even Moldova and Ukraine are considering applying, but the existence of substantial Russian minorities in both countries makes entry difficult. Hungary signed the Schengen agreement in 2007 allowing barrier free trade and travel within the Schengen zone; while Croatia, Romania and Bulgaria all plan to do so. None of the countries passed through have joined the Eurozone monetary union, but euros are widely accepted and many hotel prices are quoted in the currency. Despite being a member of the EU, Hungary has a strong nationalistic movement that dreams unrealistically of returning the country to the pre-Trianon borders of Greater Hungary.

As history has shown, this is not the first time that the whole of the lower Danube region has been politically unified. The Romans, Ottoman Turks, German Nazis and Soviet Russians all forced unity upon the region. This time unity has been achieved by democratic means!

Shipping on the river

The Danube has been a major trade artery for centuries; indeed, Genoese sailors established a number of riverside settlements in Romania in medieval times. However, the existence of fast flowing narrows such as the Iron Gates gorges made navigation difficult and sometimes dangerous. Two huge dams have tamed this natural obstruction and large barges can sail all the way upstream to Germany where, by continuing on the Rhein–Main–Donau canal, they can reach the Rhine and eventually the North Sea. Navigation was severely disrupted by the Yugoslav Civil War, when a number of bridges were destroyed and blocked the river. These have now all been cleared, but freight traffic has yet to regain pre-war volumes. Tourist boats are a very popular way of seeing the river. These mostly cruise between Passau and Budapest on the middle Danube, but some go all the way from Amsterdam to the Black Sea. Navigation on the river is controlled by an international commission. Distances on the river are marked by regular kilometre boards, which show the distance upstream from a 0km marker at Sulina near to the entrance to the Black Sea in the Danube Delta (Stage 32).

Cruise boats on their way to the Black Sea pass through the Iron Gates gorges (Stage 16)

The Danube Cycleway

The 1717km lower Danube Cycleway passes through four countries. The first 243km are in Hungary, followed by 537km through the former Yugoslav states of Croatia and Serbia. The remainder of the journey, 937km, is across the south of Romania, through the regions of Wallachia and Dobruja.

This route starts in the heart of Hungary’s capital Budapest (Stage 1), before leaving the city via the 48km-long Csepel-sziget island and then following the Danube south across the Great Hungarian plain (Stages 2–5) to reach the border with Croatia. After passing through a region slowly recovering from the Yugoslav Civil War (Stages 6–8), the Danube is crossed into the Serbian region of Vojvodina to visit the cities of Novi Sad and Belgrade (Stages 9–11).

Heading east through Serbia, using cycle tracks along long stretches of Danube flood dyke (Stages 12–14), the barrier formed by the Carpathian mountains is reached at Golubac. The next 150km is the most scenic part of the route as it follows the river through the deep and winding Iron Gates gorges traversing a gap between Carpathian (to the north) and Balkan mountains (to the south) (Stages 14–16). Emerging from the gorge before Drobeta-Turnu Severin, the route enters Romania and turns south following quiet country roads through a remote corner of Wallachia (Stages 17–18) to reach Calafat.

Veliki Kazan (Great Cauldron) is the narrowest part of the Iron Gates gorges (Stage 16)

For over 430km from Calafat to Călăraşi (Stages 19–25) our route follows the Danube road (Strada Dunarii), a road built in the mid-19th century to link riverside towns and villages in newly independent Romania. By now the river is flowing through a wide valley with a flood plain up to 30km across bounded by a river terrace that typically rises 50m above the valley floor. The mostly level route passes through a seemingly endless series of villages along the side of this flood plain, climbing occasionally on and off the river terrace. A number of riverside towns are passed, all with declining populations and surrounded by the decaying hulks of abandoned Soviet era factories. The Danube road was once lined throughout by shade giving trees, but many of these have succumbed to disease and been cut-down.

The Romanian Danube road was once tree-lined along its entire length (Stages 19–25)

At Călăraşi, where the Danube divides into two channels, the river is crossed and the going becomes hillier as the route undulates through the hills of southern Dobruja (Stages 26–27) following the eastern branch of the river. This undulating going continues as the route turns north through Dobruja, eventually reaching the foothills of the Măcin mountains (Stages 28–29). The final stages (30–32) circle these mountains, crossing the river twice to visit the two large cities of Brăila and Galaţi before ending at Tulcea, the gateway to the Danube Delta. Optional excursions allow you to visit Moldova and Ukraine (from Galaţi) and the Danube Delta (from Tulcea). There is an alternative route for Stages 27–32 through Dobruja, going from Ion Corvin to Tulcea via Constanţa and the Black Sea coast. See Appendix A for a summary of the stages.

Natural environment

Physical geography

The course of the Danube below Budapest has been greatly influenced by geomorphic events approximately 30 million years ago, when the Alps, Carpathian and Balkan mountain ranges were pushed up by the collision of the African and European tectonic plates. The Carpathians rose in a large curved S-shaped formation, passing through what are nowadays Slovakia and Romania, while the Balkans continued this curve through Serbia and Bulgaria. The Danube has cut its way between these two mountain ranges by way of the Iron Gates gorges.

Small farmers in Romania still make extensive use of horse-drawn carts

Either side of this mountain barrier, the river has created two extensive basins. The Pannonian basin takes up most of central Hungary (where it is known as the Great Hungarian plain) and extends south into Slavonia (eastern Croatia) and Vojvodina (northern Serbia). East of the mountains is the Wallachian basin, taking up the southern part of Romania. In both these basins the river has over many centuries changed its meandering course as a result of frequent flooding. This has created a swampy flood plain close to the river. Bounding this flood plain and set back from the river sometimes by as much as 30km is the low rise (between 30–50m) of a river terrace leading to a fertile plateau of sandy loess (fine wind-blown soil) formed from silt brought down by the Danube. The construction of extensive flood dykes in the Pannonian basin and the Iron Gates dams, constructed in the late 20th century between the two basins, have permanently changed the pattern of regular flooding. This has enabled the flood plains to be developed agriculturally. Farming on the plateau above the river terrace is typically arable, with wheat, maize, oilseed rape and sunflowers the main crops cultivated in very large farms. On the floodplain, smaller farms grow a mixture of crops, fruit and vegetables in addition to raising livestock. Traditional farming methods are followed in many areas, including local styles of haystacks in Serbia, mobile beehives pollinating the crops and extensive use of horse and carts in Romania and reed cultivation in the Danube Delta.

Mobile beehives on the back of large trucks are used to pollinate fields of rape and sunflowers in Romania

As the boundary between tectonic plates the region is subject to occasional earthquakes. Strong tremors greater than magnitude 7 occur on average every 58 years. The most recent (mag 7.4) was in 1986, while a mag 7.1 earthquake in 1977 severely damaged the Romanian town of Zimnicea (Stage 22).

Wildlife

While a number of small mammals and reptiles (including rabbits, hares, red squirrels, voles, water rats, weasels and snakes) may be seen scuttling across the track and deer glimpsed in forests, this is not a route inhabited by rare animals. European beaver, which had been hunted to extinction throughout the lower Danube during the 19th century, have been successfully reintroduced in a number of locations including the Gemenc national park (Hungary, Stage 4), Kopački rit nature reserve (Croatia, Stage 6) and River Olt (Romania, Stage 21) from where they have spread down river as far as the Danube Delta. As they are mainly nocturnal, your chances of seeing a beaver are slight, although you may spot a lodge. Wild boar are indigenous throughout the route, being particularly numerous in Kopački rit.

There is a wide range of interesting birdlife. White swans, geese and many varieties of ducks inhabit the river and its banks. Cruising above, raptors, particularly buzzards and kites, are frequently seen hunting small mammals. Birds that live by fishing include cormorants, noticeable when perched on rocks with their wings spread out to dry, and kingfishers. These exist in many locations, mostly on backwaters, perching where they can observe the water. Despite their bright blue and orange plumage they are very difficult to spot. Grey herons, on the other hand, are very visible and can often be seen standing in shallow water waiting to strike or stalking purposefully along the banks.

Perhaps the most noticeable birds are white storks. These huge birds, with a wingspan of two metres, nest mostly on man-made platforms. They feed on small mammals and reptiles, which they catch in water meadows or on short grassland. They are common throughout the route, particularly in southern Romania where many villages have what looks like avenues of stork nests balanced precariously on almost every telegraph pole.

Most villages in southern Romania have a number of stork nests, like this one in Năvodari (Stage 22)

Among a wide variety of reptiles, dice snakes are common around Kopăcki rit while wild land tortoise can be found in Romania’s Đerdap National Park (Stages 15–16).

Preparation

When to go

The route is generally cycleable from April to October. The best times are probably late spring (May–June) and early autumn (September–October) as it can be very hot during July and August when 40ºC is not uncommon on the Hungarian plain and in southern Romania.

How long will it take?

The main route has been broken into 32 stages averaging 54km per stage, although there is a wide variation in stage lengths from 30km (Stage 30) to 96km (Stage 19). A fit cyclist, cycling an average of 90km per day, could complete the route in 19 days. However, the main determinant of how long the trip will take is not the distance you can cycle in a day; rather it is the distance between accommodation options, particularly in Romania. Unless you are camping, or are sufficiently fluent in Romanian to ask around in villages for private accommodation, you will find it difficult to achieve a steady daily distance and should allow at least three weeks for the journey. Travelling at a gentler pace of 60km per day and allowing time for sightseeing, cycling from Budapest to the Black Sea would take four weeks.

What kind of cycle is suitable?

Most of the route is on asphalt surfaced roads or cycle tracks. However, there are some long stretches of cycling along unsurfaced flood dykes in Hungary and Serbia, and some of the road surfaces in Romania leave a lot to be desired although since Romania joined the EU they are improving rapidly. As a result, cycling the route as described in this guide is not recommended for narrow tyred racing cycles. There are on-road alternative routes which can be used to by-pass the rougher off-road sections. The most suitable type of cycle is either a touring cycle or a hybrid (a lightweight but strong cross between a touring cycle and a mountain bike with at least 21 gears). There is no advantage in using a mountain bike. Front suspension is beneficial as it absorbs much of the vibration. Straight handlebars, with bar-ends enabling you to vary your position regularly, are recommended. Make sure your cycle is serviced and lubricated before you start, particularly the brakes and chain.

As important as the cycle is your choice of tyres. Slick road tyres are not suitable and knobbly mountain bike tyres not necessary. What you need is something in-between with good tread and a slightly wider profile than you would use for everyday cycling at home. To reduce the chance of punctures, choose tyres with puncture resistant armouring, such as a Kevlar™ band.

A fully equipped cycle

Getting there and back

You may have reached Budapest by cycling the Danube Cycleway from Vienna or even from the river’s source in the German Black Forest. If you did you will have reached Szechenyi chain bridge in central Budapest, the start point for Stage 1 of this guide. If you are starting from Budapest, you can reach the city by rail, air, road or river. For a list of useful transportation websites, see Appendix E.

By rail

International rail services allow passengers to reach Budapest from all over Europe, often with a change in Vienna. However the frequent high-speed ÖBB (Austrian Railways) Railjet service from Munich and Vienna to Budapest has no cycle provision, so having arrived in Vienna it is necessary to take a series of local trains either via Bratislava to Budapest Keleti or via Bruck an de Leitha and Győr to Budapest Deli. The routes from these stations to the chain bridge are shown on the Budapest city map in Stage 1.

If travelling by rail from the UK, you can take your cycle on Eurostar from London St Pancras (not Ebbsfleet nor Ashford) to Paris Gare du Nord or Brussels Midi. Cycles booked in advance travel in dedicated cycle spaces in the baggage compartment of the same train as you. Bookings, which cost £30 single, can be made through Eurostar baggage (0344 822 5822). Cycles must be checked-in at St Pancras Eurostar luggage office (beside the bus drop-off point) at least 40mins before departure. Numbers are limited and if no spaces are available your cycle can be sent as registered baggage (£25). In this case it will travel on the next available train and is guaranteed to arrive within 24hrs. In practice, 80 per cent of the time it will travel on the same train as you. Currently there is no requirement to box your cycle, though this may change. For latest information, go to www.eurostar.com.

When you reach the continent, you and your bicycle are faced with a problem. Many of the most convenient long-distance services across Europe are operated by high speed trains that have either limited provision for cycles (French TGV) or no space at all (Thalys service from Paris and Brussels to Köln, and German ICE services). Trains from Paris to Strasbourg depart from Gare de l’Est, a short ride from Gare du Nord. Services on this route are operated by TGV or ICE high speed trains, but there are some trains with reserveable space for cycles. To find out which departures these are, look on the SNCF (French Railways) website www.voyages-sncf.com. This is in French, but less complete information is available in English at www.bikes.sncf.com. You can book French trains through this same French website or via Rail Europe www.raileurope.co.uk. From Brussels, conventional EuroCity services with cycle space run three times daily to Strasbourg via Luxembourg. In Strasbourg a local service connects across the Rhine with DB (German Railways) for connections across Germany to Munich and on through Austria to Vienna.

An alternative is to use Stena Line ferries to reach Hoek van Holland from Harwich or P&O to Rotterdam from Hull, then Dutch NS trains to Rotterdam. Here you can continue to Utrecht and catch the overnight train to Vienna, which has reclining seats, couchettes and sleeping cars together with cycle provision. On Hoek van Holland ferries, through tickets allow you to travel from London (or any station in East Anglia) to any station in the Netherlands. Booking for German trains is on www.bahn.com. Up to date information on travelling by train with a bicycle can be found on a website dedicated to worldwide rail travel ‘The man in seat 61’ www.seat61.com.

By air

Budapest airport receives direct flights from all over Europe. Airlines have different requirements regarding how cycles are presented and some, but not all, make a charge that you should pay when booking as it is usually greater at the airport. All require tyres partially deflated, handlebars turned and pedals removed (loosen pedals beforehand to make them easier to remove at the airport). Most will accept your cycle in a transparent polythene bike-bag or wrap, but some insist on the use of a cardboard bike-box. These can be obtained from cycle shops, usually for free. They can also be obtained from luggage shops at some airports, including London Heathrow, but you should ascertain their availability before leaving home.

All flights to Budapest arrive at terminal 2, which is 6km from the now closed terminal 1, on the opposite side of the airport. This makes life difficult for cyclists as the railway connection to central Budapest runs from Ferihegy station, which is adjacent to terminal 1. There is a connecting bus service, which does not carry cycles, and a motorway on which cycling is prohibited. For directions see box.

BUDAPEST AIRPORT, TERMINAL 2, TO FERIHEGY STATION

To reach Ferihegy by cycle, turn R outside terminal 2 and just before the end of the terminal buildings bear R through a gate onto a concrete block path to the R of the terminal departure road. Pass an aircraft museum R. By the entrance to this museum, turn L then R through barriers. Turn R onto an old airport perimeter road. Follow this as it turns R (signed Porta ‘J’), and after 250 metres turn L on a road with a no-through road sign. Fork R and where the road bears R, turn L onto a concrete block track passing under an advertising sign and down a short flight of steps. Cycle beside the highway for a short distance to reach traffic lights that allow you to cross over, heading towards a Shell petrol station on the opposite side. Before this filling station, turn R across another highway and immediately R again on a cycle track parallel to the road. Follow this past Vecsés shopping mall L and continue beside the highway for 3km, ignoring all turns to the L, to reach Ferihegy station. From here regular trains with cycle provision run to Budapest Nyugati station.

By road

If you travel by car you can leave it in Budapest and return by train via Bucharest when you have completed your ride. Budapest is between 1550km and 1600km from the Channel ports depending upon route.

By river

If you have the time and the money you can reach Budapest by using one of the many cruise boats that travel along the Danube. Most of these start from Passau on the German/Austrian border, but there are some that sail all the way from Amsterdam via the Rhine and the Rhein–Main–Donau canal.

Intermediate access

The only international airports passed are Osijek (Stages 6/7) and Belgrade (Stages 11/12). Giurgiu (Stages 23/24) or Olteniţa (Stages 24/25) have the nearest railway stations to Bucharest airport.

While there are no railway lines that follow the river closely, many towns passed in Hungary, Croatia and western Serbia have stations, although in eastern Serbia and Romania stations are few and far between. All railway stations are listed in the text and shown on the maps.

Getting home

The best option is to take a train to Bucharest and fly home from there. Bucharest Otopeni (Henri Coandă) airport is 16km north of the city centre. There are 12 trains per day (irregular timing and not all take cycles) on the line from Bucharest Nord to Urziceni that stop at PO Aeroport Henri Coandă station from where it is a 2.5km ride to the terminal buildings. (Turn R at exit to station parallel with railway, then L at main road. Follow this road using hard shoulder R, forking R before flyover and turning L at roundabout under flyover into airport.) Flights operate from Bucharest to many international destinations. There are no bike boxes available at the airport, but there is a wrapping service that will wrap your cycle for a fee. Alternatively, Tulcea airport, 17km south of the city following Dn22, has daily flights to Bucharest while Constanţa airport has domestic services to Bucharest and international flights to Istanbul.

You can return home by rail, although it is a long way by train from the Black Sea back to the cities of western Europe and even further to the UK. During high season (mid-June to mid-September) there is a daily direct train from Tulcea to Bucharest (which takes 5hrs 30mins) and all year there are two trains between Tulcea and Medgidia with connections to both Bucharest and Constanţa. There are regular trains between Constanţa and Bucharest, but only a few of these officially carry cycles. Romanian train details can be found at www.cfrcalatori.ro. International trains link Bucharest Nord with Budapest Keleti and there is an overnight through train to Vienna. After Budapest you will need to retrace your outbound journey.

Navigation

Waymarking

The Danube Cycleway has been adopted by the ECF (European Cyclists’ Federation) as part of EuroVelo route EV6, which runs from the Atlantic coast of France to the Black Sea. Comprehensive waymarks incorporating EV6 have been erected through Hungary and Serbia, partly so in Croatia but are not yet evident in Romania.

Principal waymarks encountered: clockwise from top left, EV6 in Hungary (definitive in green, provisional in yellow), EV6 in Croatia, EV6 fingerposts in Serbia

In Hungary EV6 is well signposted, although two kinds of EV6 waymarks are used. Those with a green background indicate the final route while those on a yellow background represent a planned route that is not yet finalised. They appear in about equal numbers, but the number of green (‘definitive’) signs is increasing. In practise this system leads to some confusion, particularly where new green signs have been installed for a definitive route but not all yellow ones removed. At one junction by the new Palace of the Arts (Stage 1) in Budapest, signs point in three directions. If you follow the route described in this guide, about half the time you will be following green waymarks and the other half you will be following yellow ones.

The Croatians have taken an altogether different and not very helpful approach to waymarking. EV6 Ruta Dunav signs appear at regular intervals, but not where you most need them. Most signs are in the middle of long straight stretches of road, very few of them are at junctions.

By contrast, in Serbia waymarking is almost perfect. EV6 Dunavska ruta finger posts appear at every junction and indicate three different kinds of route. Those with a red band show the definitive route, those with a green band an alternative asphalt route avoiding difficult or unsurfaced tracks and those with a purple band indicate side excursions to places of interest. Each sign carries a number and these numbers appear on the definitive maps published by Huber Kartographie (see below). Even in the busy streets of Belgrade city centre this system is flawless. Each of these finger posts carries a short aphorism in English, often a quote from a leading writer or philosopher.

In Romania there is no waymarking. However as most of the cycleway follows one long country route, the Danube road, this is not much of a problem. Regular well maintained kilometre stones mark every road and can be useful confirming that you are on the right route.

In the introduction to each stage an indication is given of the predominant waymarks followed.

| Summary of cycle routes followed | ||

| EuroVelo Route 6 (EV6) | Stages 1–16 | Hungary/Croatia/Serbia |

| Ruta Dunav | Stages 6–8 | Croatia |

| Dunavska ruta | Stages 9–16 | Serbia |

Maps

By far the best mapping is provided by the definitive maps of EV6 published by Huber Kartographie. These are available as an eight strip map set at 1:100,000 (ISBN 978 3 943752 17 5). Information is in German, but the mapping is clear and easy to understand. These maps are available from leading bookshops including Stanford’s, London and The Map Shop, Upton upon Severn. Do not expect to find maps available en route.

Various online maps are available to download, at a scale of your choice. Particularly useful is Open Street Map www.openstreetmap.org which has a cycle route option showing EV6 where a definitive route has been waymarked (although not in Romania).

Accommodation

Hotels, inns, guest houses and bed & breakfast

Unlike the upper and middle Danube, where accommodation is plentiful, for most of this route places to sleep are more limited with sometimes long distances between them. This becomes more acute the further east you progress. Until recently it was impossible to complete this route without using a tent to provide accommodation in remote areas. However, the number of places offering accommodation has increased as new premises have opened and it is now possible by using this guide to complete the journey without a tent. A list of accommodation is given in Appendix D. This covers rural parts of Hungary, Croatia and Vojvodina (northern Serbia). Accommodation options are not provided for towns and cities in these countries where there is a tourist office and a wide choice of accommodation. For eastern Serbia and all of Romania a full list of accommodation is given. The stage descriptions also identify all places known to have accommodation.

Hotels vary from a few expensive five star properties to more numerous local establishments. Hotels and inns usually offer a full meal service; guest houses do sometimes. Signs showing in Hungarian szoba, Croatian sobe, Romanian cazare indicate that accommodation is available. In Hungary best value is often found in a panzió (pension) or vendégház (guest house). Prices for accommodation in all countries are significantly lower than in western Europe.

Dunavski Plićak cyclists’ guest house beside the Danube flood dyke in Manastirska Rampa (Stage 13)

For full details of accommodation in Hungary, Croatia and Serbia use the internet or contact local tourist information offices. The Hungarian national tourist board has a website with a comprehensive list of all accommodation registered with local tourist offices, www.itthon.hu/szallashelyek (Hungarian, with other language options) or www.gotohungary.com/accomodation (English). An equivalent site for the Croatian tourist organisation can be found at http://croatia.hr/en-GB/Accommodation-search (English). In the Vojvodina region of Serbia the official tourist office accommodation site is www.vojvodinaonline.com/tov/smestaj. For the rest of Serbia, the National Tourist Organisation of Serbia (www.serbia.travel) has produced a booklet, Discover the Danube in Serbia, listing all accommodation along the river. This can be accessed online at www.yumpu.com/en/discover-the-danube-in-serbia. Most main towns in all three countries have tourist information offices and these are listed in Appendix C. They can provide lists of accommodation but unlike tourist offices in western Europe, do not generally offer a booking service.

In Romania there is no national accommodation database and there are no tourist offices for over 900km until you reach the delta at the end of your journey. Where there are long distances between places to stay, it is advisable to telephone ahead to ensure accommodation is available. It is sometimes possible to find accommodation by asking around in villages, but as few Romanian villagers speak any foreign languages, this is far from easy.

Youth hostels

Apart from in the cities of Budapest and Belgrade, there are only two Hostelling International youth hostels on the route (Vukovar in Croatia and Novi Sad in Serbia). In summer 2015 both were closed for refurbishment and it is not known when (or if!) they will reopen. In former communist countries ‘official youth hostels’ are still widely associated with state controlled political organisations for young people such as Pioneers or Communist youth leagues. There are, however, a number of independent hostels in major towns and cities that cater for backpackers. Many of these can be found via www.hostelbookers.com.

Camping

If you are prepared to carry camping equipment, this may appear the solution to the problem of finding accommodation, particularly in Romania. However official campsites, which are shown in the text, are few and far between. Camping may be possible in other locations with the permission of local landowners. The Romanian countryside is a surprisingly populous place, with many stages passing through a never ending string of villages, which often makes it difficult to find a spot to camp where you will not be observed or disturbed. Where there are campsites, these often have basic cabins to rent in addition to places to pitch tents.

Basic cabins can often be found at Romanian campsites such as these at Zăval (Stage 19)

Food and drink

Where to eat

Compared to the upper Danube, the number of places where cyclists can find meals and refreshments is quite limited, particularly in Romania. Locations of all places known to have restaurants, cafés or bars serving food are listed in the stage descriptions. A restaurant is an étterem (Hungarian), restoran [ресторан] (Croatian/Serbian). Menus in English or German are sometimes available in big cities and tourist areas, but are rare in smaller towns and rural locations. Indeed in smaller establishments there may be no written menu and even when a menu is provided only a few of the items listed will actually be available (the normal custom is for prices to be shown only for available items). In Romania every village has a number of small grocery stores that sell soft drinks, water and beer to consume on the premises, but meals and snacks are not available. There is, however, no problem purchasing bread, cheese, cold meats and salad items to put together a picnic lunch. Bars seldom serve food.

When to eat

Breakfast (Hungarian reggeli, Croatian doručak, Romanian mic dejun) is usually continental: breads, jam and a hot drink. In Romania this is often supplemented with eggs, cold meats, cheese and fresh vegetables.

Lunch (Hungarian ebéd, Croatian ručak, Romanian prânz) is usually the main meal of the day. For a cyclist this can prove problematic, as a large lunch is unlikely to prove suitable if you plan an afternoon in the saddle. This is particularly pronounced in Romania where lunchtime menus often have no light meals or snack items, apart from soup.

For dinner (Hungarian vacsora, Croatian večera, Romanian cina) a wide variety of cuisine can often be found, both national and international. Pork and chicken are the most common meats and beef steaks, pasta and pizza are widely available. There are, however, national and regional dishes you may wish to try.

What to eat

Hungarian cuisine is most well-known for dishes that use ample quantities of paprika (mild red pepper). Goulash (boiled beef and vegetables, flavoured with paprika) is the national dish and appears on most menus as both a soup (gulyásleves) and a main course stew (székelgulyás). Paprika is also a key ingredient in chicken paprikásh (csirkepaprikás), a casserole of chicken and vegetables thickened with sour cream. Roast goose is a favourite dish for celebrations. Stuffed cabbage (töltött káposzta) and stuffed peppers (töltött paprika) are both borrowed from Ottoman cuisine. Pancakes (palascinta) can be either savoury (such as hortobágyi palacsinta, filled with veal stew) or sweet with jam, chocolate sauce or cream cheese. Other desserts include somlói galuska, pieces of sponge cake soaked in alcohol and served with chocolate sauce and cream.

Paprika, an essential ingredient in Hungarian cuisine, on sale in Budapest’s central market

Croatian and Serbian cuisine are very similar, both being influenced strongly by Middle Eastern ways of cooking assimilated during many years of Turkish occupation. Čevapi or čevapčići (spiced meatballs), pljeskavica (minced meat patties similar to a hamburger) and ražnjiči (kebabs), all often served with green peppers and ajvar (tomato, pepper and aubergine sauce), are widely found in snack bars and restaurants. Other meats include pork, lamb, veal and beef. Karađorđeva šnicla (Karadjordje’s steak), rolled stuffed veal or pork, breaded and baked, is also known as maiden’s dream because of its erotic shape. Many small restaurants along the Danube may only serve fish, mostly šaran (carp), som (catfish), štuka (pike) or pastrva (trout). Commonly found snacks include different kinds of burek, greasy filo pastry pasties filled with cheese, meat or spinach.

Romanian meals usually start with ciorbă (‘sour’ soup) made with either burtă (tripe), peste (fish), văcuţă (beef) or legume (vegetables). A popular main course is tochitură (hearty meat stew in a spicy red pepper sauce) served with mămăligă (maize-meal polenta), cheese and a fried egg. Mici are small flat grilled minced pork patties, often sold by number from street vendors, while sarmale are cabbage leaves stuffed with meat and rice. Near the Danube, and throughout the delta, fish is abundant, most commonly crap (carp), somn (catfish) and ştiucă (pike). The most common dessert (in smaller restaurants often the only dessert) are clatite (pancakes) served with chocolate or jam.

What to drink

Hungary, Croatia, Serbia and Romania are all both beer and wine drinking countries. Beer is mostly lager style, and although apparently produced by a number of national breweries, large multinational brewers own most producers. Draught beer (Hungarian csapolt sör, Croatian točeno pivo, Romanian bere la halba) is widely available. In all four countries wine (Hungarian bor, Croatian vino, Romanian vin) quality suffered from a pursuit of quantity during the communist era, but has been steadily recovering since.

In Hungary vineyards spread throughout the country produce large quantities of table wine mostly from Kadarka red grapes or Olasz white grapes (a variety of Riesling). More well-known are full bodied golden white wines, slightly sweet but fiery and peppery and an ideal accompaniment to spicy Hungarian food, and Bull’s Blood, a full-bodied red made from Bikavér grapes. Most famous of all is Tokay, a dessert wine from northeast Hungary made by a unique process where the sweet pulp of over-ripe rotted Furmint grapes (known as aszú) is added to barrels of one-year-old wine and left to mature for at least three more years.

In the former Yugoslav countries the tendency is for white wine to be produced inland to the north in Slovenia, northern Croatia and Vojvodina (northern Serbia) while red wine comes mostly from the south and the coastal regions of eastern Croatia, southern Serbia and Macedonia. The Danube valley is a major white wine producing area in both Croatia and Serbia, with Croatian vineyards on the slopes of the Bansko Brdo ridge (Stage 6) and around Vukovar and Ilok (Stages 7 and 8). This wine region extends into the Serbian foothills of the Fruška Gora mountains (Stage 10), with further Serbian vineyards south of Belgrade. Principal varieties are Graševina (a local grape), Traminer and Italian Riesling. The main local red grape is Prokupac, but this is declining in favour of international grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot.

Romania is the world’s ninth largest wine producer, but little is exported. Prior to the Second World War most of Romania’s wine came from eastern Moldavia, an area that was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945. The communist government replaced this lost acreage by planting state operated vineyards mainly in northern Wallachia, south of the Carpathians, which produced large quantities of cheap wine. Since the fall of communism many of these vineyards have been replanted with international varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc to produce better quality wine. Some local grapes have survived, the most common being Fetească Neagră (used for roşu (red) wine), Fetească Albă and Fetească Regală which both produce alb (white) wine. Tămâioasă grapes (similar to Muscat) produce sweet wine. Cotnari is a sweet dessert wine very like Hungarian Tokay, made from Grasă grapes. The Danube passes close to two of Romania’s better quality wine growing areas: around Segarcea (30km north of Cârna, Stage 19) and in southern Dobruja near Lipniţa (Stage 26) and around Murfatlar (Stage 27). One problem with buying wine in Romanian bars and restaurants is that it is almost always sold by the bottle (750ml) or by litre carafe. It is impossible to buy wine by the glass.

In all four countries the most popular spirit is fruit brandy. Hungarian Pálinka can be distilled from apricots, plums or pears, while Croatian and Serbian Šljivovica (sometimes called Rakija) and Romanian Ţuică are plum brandies. All are frequently home distilled, particularly in Romania and can vary from smooth and sweet to strong and fiery.

All the usual soft drinks (colas, lemonade, fruit juices, mineral waters) are widely available. Tap water is normally safe to drink in all four countries although if you are susceptible to stomach upsets caused by water that differs from your domestic supply, bottled water is on sale everywhere.

Amenities and services

Grocery shops

In Hungary, Croatia and Serbia all cities and towns passed through have grocery stores, often supermarkets, and most have pharmacies. In Romania every village has a number of small general grocery stores often with a table and chairs outside where local residents can be found drinking beer at any time of day.

Every Romanian village has a number of small grocery shops combined with a bar like this one in Ciocăneşti (Stage 25)

Cycle shops

Cycle shops and repair facilities are few and far between, particularly in Romania. A basic knowledge of cycle maintenance, particularly mending a puncture, adjustment of brakes and gears, replacement of broken spokes and repairing a broken chain might come in useful.

Currency and banks

The Hungarian currency is the Forint, although many tourist oriented businesses such as hotels and restaurants will accept payment in euros. In Croatia the official currency is the Kuna, but as the euro is closely tracked by the Kuna, it is widely accepted here too. It is likely that Croatia will join the Eurozone during the lifetime of this guide.

Serbians use the Dinar, a direct successor of the Yugoslav Dinar while the currency in Romania is the Lei. In both countries the best rates of exchange are usually obtained by taking cash (pound sterling, euro or US dollar) and exchanging it locally in registered exchange offices rather than banks; the days of an active black market are long gone. In both countries euros are widely accepted in tourist oriented businesses, indeed hotel prices are often quoted in euros. Cross-exchange of local currencies is surprisingly difficult, even at border crossings. Because of this you should avoid changing too much currency as you may not be able to exchange it back after you leave the country.

Almost every town has a bank and many have ATM machines which enable you to make transactions in English. Contact your bank to activate your bank card for use in Europe.

Telephone and internet

The whole route has mobile phone coverage. Contact your network provider to ensure your phone is enabled for foreign use with the optimum price package. International dialling codes from UK (+44) are:

Hungary+36

Croatia+385

Serbia+381

Romania+40

Almost all hotels, guest houses and hostels make internet access available to guests, usually free.

Electricity

Voltage is 220v, 50HzAC. Plugs are standard European two-pin round.

What to take

Clothing and personal items

Even though the route is generally level, weight should be kept to a minimum. You will need clothes for cycling (shoes, socks, shorts/trousers, shirt, fleece, waterproofs) and clothes for evenings and days off. The best maxim is two of each, ‘one to wear, one to wash’. The time of year will make a difference as you need more and warmer clothing in April/May and September/October. All of this clothing should be capable of washing en route, and a small tube or bottle of travel wash is useful. A sun hat and sunglasses are essential, while gloves and a woolly hat are advisable in spring and autumn.

In addition to your usual toiletries you will need sun cream and lip salve. You should take a simple first-aid kit. If staying in hostels you will need a towel and torch (your cycle light should suffice). Mosquitoes can be a problem in rural areas in summer, particularly if camping, and both insect repellent and sting relief lotion should be carried.

Cycle equipment

Everything you take needs to be carried on your cycle. If overnighting in accommodation, a pair of rear panniers should be sufficient to carry all your clothing and equipment, but if camping, you may also need front panniers. Panniers should be 100 per cent watertight. If in doubt, pack everything inside a strong polythene-lining bag. Rubble bags, obtainable from builders’ merchants, are ideal for this purpose. A bar-bag is a useful way of carrying items you need to access quickly such as maps, sunglasses, camera, spare tubes, puncture-kit and tools. A transparent map case attached to the top of your bar-bag is an ideal way of displaying maps and guidebook.