Читать книгу The River Rhone Cycle Route - Mike Wells - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Running from the Swiss Alps to the Mediterranean Sea, the valley of the river Rhone has for many centuries been one of the great communication links of western Europe. The Romans conquered Gaul by marching their legions up the lower Rhone valley from the sea, while over 1850 years later the French Emperor Napoleon took his army the other way by using the upper valley as his route to invade Italy. For modern-day French families the lower Rhone valley is the ‘route du soleil’ (route to the sun) which they follow every summer to reach vacation destinations in the south of France. For much of its length the river is followed by railways, roads and motorways carrying goods to and from great Mediterranean ports such as Marseille and Genoa.

In addition to being a major transport artery, the Rhone valley is host to an attractive long distance cycle route that makes its way for nearly 900km from the high Alps to the Rhone delta using a mixture of traffic free tracks and country roads. As it follows a great river, the route is mostly downhill.

After many years of planning and construction, the Rhone Cycle Route has reached a level of completion that makes it a viable means of cycling from central Switzerland to the south of France in a generally quiet environment by using two waymarked national cycle trails: the Swiss R1 Rhone Route and the French ViaRhôna. These have been adopted by the ECF (European Cyclists’ Federation) as EuroVélo route EV17. This guide breaks the route into 20 stages, averaging 45km in length. A reasonably fit cyclist, riding 75km per day should be able to complete the route in 12 days. Allowing for a gentler ride with time for sightseeing on the way, the route can be cycled in a fortnight by most cyclists.

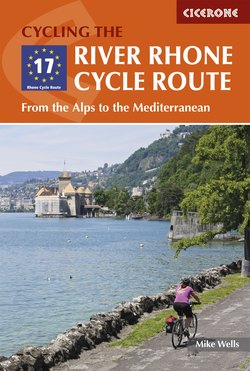

The shore of Lake Geneva in Montreux is lined with floral displays (Stages 4 and 5)

The Swiss R1 Rhone Route, part of the extensive Swiss Veloland network, is complete running from the river’s source near the summit of the Furkapass for 321km to the border between Switzerland and France at Chancy, west of Geneva. En route it follows a deep glacial valley with snow-capped mountains rising on both sides, some of the highest in Switzerland, to reach Lake Geneva. Attractive cities and towns such as Montreux, Lausanne, Geneva and Evian line the lake, which is both a popular tourist destination and one of the most prosperous parts of Switzerland.

After crossing into France, the ViaRhôna is followed, firstly through a deep limestone gorge between the Jura mountains and the Savoy Alps, then after passing through Lyon, France’s second city, through another wider gorge along the geological fault line between the Alps and Massif Central to reach the Mediterranean. The main cities along this valley, Lyon, Valence and Arles, have history going back before Roman times and much evidence of Roman civilisation including the ruins of temples, arena, amphitheatres and bath-houses. Other cities, particularly Vienne and Avignon, were important medieval religious centres with large cathedrals and clerical palaces.

ViaRhôna (www.viarhona.com) is a dedicated cycle track being built to French voie verte standards (traffic-free, 3m wide, asphalt surface) all the way from the Swiss border to the sea. While this is about 75 percent complete, there are sections, particularly in Isère département and south of Pont-St Esprit, where quiet country roads need to be used. Heavy traffic is only encountered on one stage, when heading south out of Lyon (Stage 11). This can be avoided if desired by taking the train for 30km from Lyon to Vienne.

Throughout the route there are a wide variety of places to stay, from campsites through youth hostels, guest houses and small family run hotels all the way up to some of the world’s greatest five-star hotels. Local tourist offices in almost every town will help you find accommodation, and often book it for you. It is the same for food and drink, with eating establishments in every price range including two of France’s most famous (and expensive!) three-star Michelin restaurants (Paul Bocuse near Lyon and Maison Pic in Valence). In both Switzerland (where the birthplace and grave of César Ritz is passed on Stage 1) and France, where culinary skills are in evidence in almost all establishments, even the smallest local restaurants offer home-cooked meals using quality local ingredients. If you like wine, there are plentiful opportunities to sample local vintages in both countries as the route passes through the Swiss wine producing areas of Valais, Lavaux and La Côte and many French ones including Côte-Rôtie, Condrieu, Hermitage, Châteauneuf-du-Pape and Côtes-du-Rhône.

Vineyards of Lavaux cover the lakeside slopes between Vevey and Lausanne (Stage 5)

Background

The Rhone cycle route passes through two countries. Although both countries speak French (albeit partly so in Switzerland) they have very different history, culture and ways of government.

Switzerland

Switzerland is a federation of 26 cantons (federal states). It was founded in 1291 (on 1 August, now celebrated as Swiss national day), although some of west Switzerland through which the route passes did not join the federation until 1803. Modern Switzerland is regarded as a homogenous, prosperous and well organised country, but it was not always the case.

Roman occupation

Before the arrival of the Romans in 15BC, the land north of the Alps that is modern Switzerland was inhabited by the Helvetii, a Gallic Iron Age tribe. More than 400 years of Roman rule left its mark with many archaeological remains. During the fourth century AD, the Romans came under increasing pressure from Germanic tribes from the north and by AD401 had withdrawn their legions from the region.

Early Swiss history

After the Romans departed, two tribes occupied the area: the Burgundians in the west and Alemanni in the east. This division lives on 1600 years later in the division between the French and German speaking parts of Switzerland. The Burgundian territory south of Lake Geneva passed through a number of hands before becoming part of Savoy in 1003. North of the lake the territory became divided between a number of city states, all part of the Holy Roman Empire. The Alemanni territory became part of Berne, also within the Holy Roman Empire. Expansionist Berne joined the Swiss Federation in 1353 and gradually absorbed all the city states (except Geneva), leaving Berne and Savoy facing each other across the lake. Most of the fortifications in western Switzerland are either Bernese or Savoyard and reflect regular tensions between these countries. Both were feudal states with a large number of peasants ruled over by noble elites.

Château de Chillon was a Savoyard castle captured by the Bernese (Stage 4)

Napoleonic era

This division ended when French revolutionary forces invaded Savoy (1792) and Napoleon invaded Geneva and Berne (1798) bringing the whole region temporarily under French control. Napoleon re-established a Swiss Confederation in 1803, separating Valais from Savoy and breaking up Berne into smaller cantons including Vaud. The feudal structure was abolished and the cantons in this confederation were set up with governments based on democratic principles. After Napoleon’s fall (1815), the Congress of Vienna gave Savoy to the kingdom of Sardinia, a nation that already controlled neighbouring Piedmont in northern Italy. This congress also recognised Swiss neutrality.

Nineteenth-century Switzerland

For most of the 19th century, Switzerland remained one of Europe’s poorest countries, relying upon agriculture with very little industry or natural resources. The coming of railways that enabled rich visitors from northern Europe to visit the Alps and the attraction of clean air and medical facilities for those with consumption and bronchitis started to lift the Swiss economy. The development of hydro-electric generation gave Switzerland plentiful cheap energy and spurred the growth of engineering businesses. Swiss banks in Zurich and Geneva, with a policy of secrecy and a reputation for trust, attracted funds from foreign investors who wished to avail themselves of these benefits.

Modern-day prosperity

Although neutral and not involved in the fighting, Switzerland suffered badly during the First World War when foreign visitors were unable to reach the country and markets for its engineering products dried up. Post war recovery was led by the banking sector. Political and economic turmoil in Russia and Germany boosted Swiss bank receipts. Swiss neutrality made it the obvious location for multinational bodies such as the League of Nations and the International Red Cross. The Swiss economic miracle has continued since the Second World War with industries such as watch making, precision engineering and electrical generation becoming world leaders. Modern-day Switzerland has the highest nominal capital per head in the world and the second highest life expectancy. Transport systems by rail and road are world leaders and the country has an aura of order and cleanliness. The Swiss are justifiably proud of what they have achieved. European Union member countries surround Switzerland but it is not a member. The Swiss have however signed the Schengen accord, creating open borders with their neighbours, and are participants in the European Health Insurance Card system allowing free emergency medical treatment to European visitors.

The neutrality conundrum

Switzerland has a policy of armed neutrality with one of the highest levels of military expenditure per head in Europe. All Swiss men undertake military service with approximately 20 weeks’ training upon reaching the age of 18, followed by annual exercises until 35. Conscripts keep their weapons and uniforms at home and it is common on Saturday mornings to find trains busy with armed men going to annual camp. Prior to 1995 it was Swiss policy to sit out a nuclear war by retiring to nuclear bunkers and emerging unharmed when it was all over. All new buildings were built with nuclear shelters; these still exist with many used as underground garages or storerooms. Meanwhile the Swiss armed forces would retreat to fully equipped barracks in the fastness of the Alps, one of which is passed on Stage 4 at St Maurice. Airstrips were built in alpine valleys with camouflaged hangars holding fighter aircraft ready to fly. Referenda in 1995 and 2003 scrapped this policy and reduced the armed forces from 400,000 to 200,000, although conscription remains.

Swiss languages

While it might appear that Switzerland with four official languages, German (spoken by 72 percent of the Swiss population), French (22 per cent), Italian (six per cent) and Romansh (under one per cent), is a multi-lingual country, this is far from being true. Federal government business is conducted in German, French and Italian and school students are required to learn at least two languages. However, in most cantons, business is mono-lingual and it is sometimes difficult to find people willing to speak any Swiss language other than their own. Even Valais, where German is spoken in part of the canton and French in the rest, is not officially bi-lingual. The only places in Switzerland where bi-lingualism is legally prescribed are three towns that sit astride the isogloss (language border) including Sierre/Siders (Stage 2).

France

The Fifth French republic is the current manifestation of a great colonial nation that developed out of Charlemagne’s eighth-century Frankish kingdom and eventually spread its power throughout Europe and beyond.

Roman France

Before the arrival of the Romans in the first century BC, the part of France through which the Rhone flows was inhabited by Iron Age Celtic tribes such as the Gauls (central France) and Allobroges (Alpine France). The Romans involved local tribal leaders in government and control of the territory and with improvements in the standard of living the conquered tribes soon became thoroughly romanised. Roman colonial cities were established at places such as Lyon (Stage 10), Vienne (Stage 11) and Arles (Stage 19), with many other settlements all along the Rhone. During the fourth century AD, the Romans came under increasing pressure from Germanic tribes from the north and by AD401 had withdrawn their legions from the western Alps and Rhone valley.

Vienne’s temple of Augustus and Livia is one of the best preserved Roman buildings in France (Stage 11)

The Franks and the foundation of France

After the Romans left there followed a period of tribal settlement. The Franks were a tribe that settled in northern France. From AD496, when Clovis I became their king and established a capital in Paris, the Frankish kingdom expanded by absorbing neighbouring states. After Charlemagne (a Frank, AD768–814) temporarily united much of western Europe, only for his Carolingian empire to be split in AD843, the Franks became the dominant regional force. Their kingdom, which became France, grew with expansion in all directions. To the southeast, the Dauphiné (the area between the Rhone and the Alps) was absorbed in 1349, Arles in 1378, Burgundy (north of Lyon) in 1477, Provence (the Mediterranean littoral) in 1481 and Franche-Comté (Jura) in 1678. Strong kings including Louis XIV (1638–1715) ruled as absolute monarchs over a feudal kingdom with a rigid class system, the Ancien Régime. In many towns the church held as much power as the local nobility. Avignon was papal territory, ruled by a legate appointed by the Pope.

The French Revolution

The ancien régime French kingdom ended in a period of violent revolution (1789–1799). The monarchy was swept away and privileges enjoyed by the nobility and clergy removed. Monasteries and religious institutions were closed. In place of the monarchy a secular republic was established. The revolutionary mantra of ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité‘ is still the motto of modern-day France. Chaos followed the revolution and a reign of terror resulted in an estimated 40,000 deaths, including King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette. A coup in 1799 led to military leader Napoleon Bonaparte taking control.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Despite ruling France for only 16 years, Napoleon (1769–1821) had a greater influence on the political and legal structures of Europe than any other person. He made peace with the Catholic church and allowed many exiled aristocrats to return, although with limited powers. In 1804 he declared himself Emperor of France and started on a series of military campaigns that saw the French gain control of much of western and central Europe. Perhaps the longest lasting of the Napoleonic reforms was the ‘Code Napoléon’, a civil legal code that was adopted throughout the conquered territories and remains today at the heart of the European legal system. When he was defeated in 1815, by the combined forces of Britain and Prussia, he was replaced as head of state by a restoration of the monarchy under Louis XVIII, brother of Louis XVI.

Nineteenth-century France

Politically France went through a series of three monarchies, an empire headed by Napoleon III (Bonaparte’s nephew) and two republics. Napoleon III’s intervention in the reunification of Italy led to Savoy becoming part of France in 1860. During this period the French economy grew strongly based upon coal, iron and steel and heavy engineering. A large overseas empire was created, mostly in Africa, second in size to the British Empire. Increasing conflict with Prussia and Germany led to defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1870) and involvement in the First World War (1914–1918).

Twentieth-century France

Despite being on the winning side, the French economy was devastated by the war and the depression of the 1930s. Invasion by Germany in the Second World War (1939–1945) saw France partitioned temporarily with all of southern France becoming part of Vichy, a nominally independent state that was in reality a puppet government controlled by the Germans. After the war, France was one of the original signatories to the Treaty of Rome (1957) which established the European Economic Community (EEC) and led to the European Union (EU). Economic growth was strong and the French economy prospered. Political dissent, particularly over colonial policy, led to a new constitution and the establishment of the fifth republic under Charles de Gaulle in 1958. Since then, withdrawal from overseas possessions has led to substantial immigration into metropolitan France from ex-colonies, creating the most ethnically diverse population in Europe. Large cities like Lyon have suburbs with substantial immigrant populations. Since the 1970s, old heavy industry has almost completely disappeared and been replaced with high tech industry and employment in the service sector.

Shipping on the river

Since Roman times the lower Rhone has been the main trade and communication route between the Mediterranean and central France, although strong currents and flooding caused by ice-melt in spring and low water levels in summer made navigation difficult. In the medieval period freight was carried up-river in barge trains pulled by men and as many as 80 horses plodding along the towpath. Going downstream the barges were carried freely by the current. As the towpath was only used in one direction it is known in French as the chemin de contre-halage. Steam powered boats replaced horses in the early 19th century. These were driven by two paddlewheels with some having a huge claw-wheel that gave extra power by gripping the riverbed. After the Second World War, steamboats were replaced by diesel powered barges. Tourist cruise boats operate on the lower river between Port-St Louis-du-Rhône and Lyon. Kilometre posts beside the river show the distance downstream from the confluence of Rhone and Saone in Lyon.

Cruise boats operate between Lyon (Stage 10) and Port-St-Louis-du-Rhône (Stage 20)

In 1933, the Compagnie Nationale du Rhône (CNR) was established to control the river. Work was halted by the Second World War but restarted in 1948. A series of 19 dams, 17 locks and a number of canal cuts have been constructed since then to improve navigation, generate electricity, control flooding and irrigate farmland. While the major works were completed in 1986, ongoing projects to open up the middle river above Lyon are continuing. The latest lock at Virignin (Stage 8) opened in 2012. Two dams have boat portage ramps (Brégnier–Cordon and Sault-Brénaz), although there are long-term plans to replace these with locks. When this infrastructure has been completed the river will be fully open to leisure craft as far as Seyssel, 461km from the Mediterranean.

Further upstream, the Seujet dam in Geneva (Stage 7) is the most important structure controlling both the level of Lake Geneva and the amount of water released into the Rhone. From 1894 the lake level was controlled by hand-operated sluices until being replaced by a hydro-electric dam in 1995.

The source of the Rhone is in the high Alps beside the Furkapass (Stage 1)

The Rhone Cycle Route

The 895km Rhone Cycle Route starts in the high Alps of central Switzerland, then heads west past Lake Geneva into France before turning south to reach the Mediterranean near Marseille. The first 321km in Switzerland pass through the cantons of Valais, Vaud and Geneva, while 574km in France mostly traverse the Rhône-Alpes region. Towards the end, the route follows the boundary between the Languedoc-Roussillon and Provence-Alpes-Côte-d’Azur regions.

This route (Stage 1) starts at the Rhone glacier viewpoint beside the Belvédère hotel, just west of the Furkapass summit. From here it plunges 900m downhill on the Furkapass to Oberwald then continues gently downhill through Goms, the pastoral valley of the infant Rhone. Near Ernen, where the Rhone descends a moraine, the route climbs away from the river on a track above the Binntal gorge through the Binntal nature park. Returning to the valley, it continues through the upper part of Valais canton (Stage 2) passing the industrial towns of Brig and Visp. Between Leuk and Sierre, where the river drops over a second moraine, the route again leaves the river, this time following a main road through Forêt de Finges pine forest. Between Sierre and Martigny (Stage 3), where the valley turns to head north, and again from Martigny to Lake Geneva (Stage 4), the wide straight valley is lined by vineyards and bounded by the snow-capped peaks of the Diablerets and Dents du Midi ranges. There are alternative routes around Lake Geneva: one passes north of the lake through Montreux and Lausanne (Stages 5–6) and the other south through Evian and Thonon-les-Bains (Stages 5A–6A). These come together in the cosmopolitan city of Geneva, which straddles the border between Switzerland and France.

Entering France, heading first southwest and then northwest, the route follows the winding river through the Rhone gorge cutting between the Jura and the Savoy Alps (Stages 7–9) with limestone cliffs on both sides. On Stage 10 population density increases as the route approaches Lyon, France’s second largest city and gastronomic capital. From here it turns south (Stages 11–17) following a wide relatively straight valley between the Alps to the east and Massif Central to the west, passing historic cities such as Vienne, Valence and Montélimar. This is an important transport route from northern Europe to the Mediterranean and the valley is followed by three railways (passenger, freight and high-speed), a national road (N7) and motorway (A7), although these seldom impinge upon the cycle route. South of Vienne (Stage 12) vineyards line the valley and after Valence (Stage 15), which styles itself as ‘gateway to the south’, the climate becomes mild enough for olives to survive the winter.

Beyond the Papal capital of Avignon (Stage 18) the route reaches the flat lands of the Mediterranean littoral and the way of life, architecture and landscape become recognisably Provençale, immortalised by Vincent van Gogh in his paintings of the area around Arles (Stage 19). The final leg (Stage 20) takes the route through the sparsely inhabited flat lands of the Rhone delta, known as the Camargue, to reach the Mediterranean 40km west of Marseille. See Appendix A for a breakdown of the starting and finishing points and the distance covered by each stage.

Natural environment

Physical geography

The course of the Rhone has been greatly influenced by geological events approximately 30 million years ago, when the Alps were pushed up by the collision of the African and European tectonic plates. As well as forming the Alps, this caused rippling of the landmass to the north, creating a ridge that forms the limestone mountains of the Jura and pushing up the older hard rocks of the Massif Central. Subsequent glaciation during a series of ice ages resulted in the Rhone cutting a series of deep U-shaped valleys through the high Alps (Stages 1–4). At the base of the glaciers a large lake formed (Lake Geneva, Stages 5–6). The outflow from this lake cut a winding gorge between the Jura mountains and Savoy Alps (Stages 7–10). At Lyon where the river reached the hard rock of the Massif Central it was forced south through the wide and straight sillon Rhôdanien (Rhone furrow) all the way to the Mediterranean (Stages 11–18). As this valley was subject to frequent flooding the river developed a winding course through a marshy environment. For most of its length the river cuts down through soft limestone and carries large quantities of sediment. Some of this sediment is deposited in Lake Geneva, which is slowly filling up though it will take many thousands of years to fill completely. The rest is carried down to the flat lands of the Mediterranean littoral (Stages 19–20), where the slow flowing Rhone has deposited considerable quantities of sediment to form the Camargue delta.

The Rhone is the only one of Europe’s great rivers that has an ‘active’ glacier as its main source, although this is now only 7km long compared with a length of 140km at the end of the last ice age 14,000 years ago. As the glacier retreated it left three terminal moraines (large piles of eroded rubble brought down by the glacier), which are crossed en-route. The glacier is still retreating at about 10m per year and at this rate will disappear altogether in 700 years.

The Rhone is fed by a number of important tributaries including the Saône (draining the western slopes of the Jura) and the Isère, which rises in the Savoy Alps south of Mont Blanc.

Wildlife

While chamois and ibex can be found in the mountains near the source and a number of small mammals (including rabbits, hares, red squirrels, voles, water rats and weasels) may be seen scuttling across the track and deer glimpsed in forests, this is not a route for seeing wild animals. However, there are a few places where old bends of the river, abandoned since navigational improvements have made them redundant, have been turned into nature reserves. Of particular note is Printegarde nature reserve (Stage 15), home to many varieties of birds, animals and insects including black kites, storks, bee-eaters, European beaver and 40 varieties of dragonfly.

In the Camargue (Stage 20), two species of semi-feral animal can be found – black cattle and white horses. These animals are privately owned and tended by local gardians (cowboys) but allowed to roam on the salt flats and marshes. The bulls are used to provide animals for local bull fights and for meat, while the horses are used as mounts for the gardians and for equestrian sports such as dressage and three-day-eventing.

Gardians (cowboys) from the Camargue gather in Arles for the bull running (Stage 19)

There is a wide range of interesting birdlife. White swans, geese and many varieties of ducks inhabit the river and its banks. Cruising above, raptors, particularly buzzards and kites, are frequently seen hunting small mammals, while flamingos can be found in the Camargue. Birds that live by fishing include cormorants, noticeable when perched on rocks with their wings spread out to dry, and grey herons, which can be seen standing in shallow water waiting to strike or stalking purposefully along the banks.

Preparation

When to go

With the exception of the first 14km of Stage 1 from the source beside the Furkapass to Oberwald, the route is generally cycleable from April to October. The Furkapass is blocked by snow in winter and is usually closed from November until May, exact dates varying from year to year depending upon snow levels. Indeed, snow can fall at any time of year, but is rare in July and August. The Postbus service over the pass, which can be used to reach the start of the route, runs only between mid-June and mid-October. As a result, unless you plan to cycle up to the source from Oberwald or Realp, the full ride can only be completed during summer and early autumn.

How long will it take?

The main route has been broken into 20 stages averaging 45km per stage. A fit cyclist, cycling an average of 75km per day should be able to complete the route in 12 days. A schedule for this timescale appears in Appendix C. Travelling at a gentler pace of 60km per day and allowing time for sightseeing, cycling the Rhone to the Mediterranean would take a fortnight. There are many places to stay all along the route making it is easy to tailor daily distances to your requirements.

What kind of cycle is suitable?

Most of the route is on asphalt cycle tracks or alongside quiet country roads. There are some stretches with gravel surfaces, particularly in Switzerland, but these are invariably well graded and pose few problems for touring cycles. However, cycling the exact route described in this guide is not recommended for narrow tyred racing cycles. There are on-road alternatives which can be used to by-pass the rougher sections. The most suitable type of cycle is either a touring cycle or a hybrid (a lightweight but strong cross between a touring cycle and a mountain bike with at least 21 gears). There is no advantage in using a mountain bike. Front suspension is beneficial as it absorbs much of the vibration. Straight handlebars, with bar-ends enabling you to vary your position regularly, are recommended. Make sure your cycle is serviced and lubricated before you start, particularly the brakes, gears and chain.

As important as the cycle is your choice of tyres. Slick road tyres are not suitable and knobbly mountain bike tyres not necessary. What you need is something in-between with good tread and a slightly wider profile than you would use for everyday cycling at home. To reduce the chance of punctures, choose tyres with puncture resistant armouring, such as a Kevlar™ band.

A fully equipped cycle at Furka Belvédère (Stage 1)

Getting there and back

By rail

The start of the route near the summit of the Furkapass is not directly accessible by train. However, there are stations at Realp (east of the pass) and Oberwald (to the west) that are served by hourly year-round MGB (Matterhorn Gotthard Bahn) narrow gauge trains between Andermatt and Brig. During the peak summer season (mid-June to mid-October) there is a Postbus service over the pass with two departures daily from Andermatt and three from Oberwald. These buses carry a limited number of cycles with reservations required before 4.00pm the previous day (PostAuto Schweiz, Region Bern/Zentralalpen; +41 58 448 20 08; www.postauto.ch/bern). You can cycle up the pass, but this is a steep 900m climb on a main road from either Realp or Oberwald!

Postbus services from Andermatt to Furka Belvédère carry up to six cycles (Stage 1)

Andermatt can be reached by hourly SBB (Swiss railways) services from Basle or Zürich, changing at Göschenen. Oberwald is accessed by hourly SBB services from Geneva and Lausanne, changing at Brig. Most trains on both routes (except CIS and Glacier Express) have cycle space. Swiss trains do not require seat reservations, although cycle reservation is mandatory (for a fee of CHF5) on ICN intercity trains, which operate about 50 per cent of the services between Basle or Zürich and Göschenen. In Switzerland a ticket is required for your cycle. This costs CHF15 and covers all journeys within a day. Tickets can be purchased and reservations made at www.sbb.ch.

If travelling from the UK, you can take your cycle on Eurostar from London St Pancras (not Ebbsfleet nor Ashford) to Paris (Gare du Nord) or Brussels (Midi). Trains between London and Paris run hourly throughout the day, taking under three hours. Cycles booked in advance travel in dedicated cycle spaces in the baggage compartment of the same train as you. Bookings, which cost £30 single, can be made through Eurostar baggage (0844 822 5822). Cycles must be checked in at St Pancras Eurostar luggage office (beside the bus drop-off point) at least 40mins before departure. There is no requirement to package or dismantle your cycle. There is more information at www.eurostar.com.

CROSSING PARIS

After arrival in Paris you need to cycle from Gare du Nord to Gare de Lyon following a series of grand boulevards (wide avenues) on an almost straight 4km route.

Go ahead opposite the main entrance to Gare du Nord along Boulevard de Denain, a one-way street with contra-flow permitted for cyclists. At the end turn L into Boulevard de Magenta and follow this to reach Place de la Republique. Continue round this square and leave on the opposite side by Boulevard du Temple, becoming Boulevard des Filles du Calvaire then Boulevard Beaumarchais, to reach Place de la Bastille. Bear L (past a memorial column to 1830 revolution) and R (passing Opera Bastille L) into Rue de Lyon to reach Gare de Lyon station.

Franco Swiss Lyria TGV high-speed trains, which run from Paris (Gare de Lyon) to Basle and on to Zürich, have four cycle spaces per train, with mandatory reservation (€10). There are six direct trains per day, which take 3hrs. Alternatively there are seven Lyria trains daily between Paris and Geneva (3hrs) and four to Lausanne (3hrs 40mins). Details can be found on SNCF (French Railways) website, http://uk.voyages-sncf.com.

If travelling from Brussels to Basle you face the problem that high-speed Thalys trains between Brussels and Köln and ICE intercity express trains in Germany do not carry cycles. However, conventional EuroCity services with cycle space run three times daily directly to Basle via Luxembourg and Strasbourg. Provision of cycle space on European trains is steadily increasing and up-to-date information on travelling by train with a bicycle can be found on a website dedicated to worldwide rail travel ‘The man in seat 61’, www.seat61.com.

An alternative is to use Stena Line ferries to reach Hoek van Holland from Harwich or P&O to Rotterdam from Hull, then Dutch NS trains to Rotterdam. Here you can connect via Venlo and Dusseldorf with DB (German Railways) services, with cycle provision, that will take you on to Basle. On Hoek van Holland ferries, through tickets allow you to travel from London (or any station in East Anglia) to any station in the Netherlands. Booking for German trains is possible on www.bahn.com.

By air

Airports at Zürich (2hrs 30mins by train to Andermatt), Basle (3hrs but you need to cycle from the airport to Basle station) or Geneva (4hrs to Oberwald), all served by a variety of international airlines, can be used to access the Rhone source. Airlines have different requirements regarding how cycles are presented and some, but not all, make a charge, which you should pay when booking as it is usually greater at the airport. All require tyres partially deflated, handlebars turned and pedals removed (loosen pedals beforehand to make them easier to remove at the airport). Most will accept your cycle in a transparent polythene bike-bag, although some insist on use of a cardboard bike-box. These can be obtained from cycle shops, often for free, and may be purchased at some airports, including all terminals at Heathrow and Gatwick (Excess Baggage Company, www.left-baggage.co.uk).

By road

If you are lucky enough to have someone prepared to drive you to the start, Furkapass Belvédère is 2.5km west of Furkapass summit on Swiss national road 19 between Brig and Andermatt. With your own vehicle the most convenient place to leave it is Geneva, from where trains can be used to reach Oberwald on the outward journey, and which can be reached by train from Marseille on the return (see below). Geneva is between 800km and 825km from the Channel ports depending upon route.

European Bike Express operates an overnight coach service with dedicated cycle trailer from Northern England, picking up en route across England to the Mediterranean, with a drop-off point at Mâcon in eastern France. The journey time is between 13hrs and 22hrs depending on where the coach is joined. Details and booking through www.bike-express.co.uk. Trains link Mâcon with Geneva.

Intermediate access

There are international airports at Geneva (Stages 6 and 6A), and Lyon (Stage 10). The airports at Sion (Stage 3) and Avignon (Stage 18) have very few international flights. Much of the route is closely followed by railway lines. Stations en route are listed in the text.

Getting home

The nearest station to Port-St Louis-du-Rhône is at Fos-sur-Mer, 25km away by main road on the opposite side of the Golfe de Fos. The route to the station is described at the end of Stage 20. From here regional local trains run to Miramas where you can connect with TER trains to reach Avignon Centre. Alternatively, local buses (route 021) operated by Cartreize from Port-St Louis Douane (bus stop beside the blue lifting bridge) to Arles carry a limited number of cycles under the bus, with four services Monday–Saturday, two on Sundays. Details are available from Cartreize (+33 810 00 13 26), www.lepilote.com. From Arles, TER trains will take you to Avignon Centre.

Occasional TGV trains that carry cycles run from Avignon Centre to Paris Gare de Lyon, with mandatory reservation required. From Gare de Lyon you can cycle to Paris Gard du Nord (reverse of outbound route described above) and catch Eurostar to London. There is a direct afternoon Eurostar service from Marseille to London, but this does not convey cycles. If you left a car in Switzerland, catch a local train from Fos-sur-Mer to Marseille St Charles for a direct TGV service to Geneva. To fly home there are frequent trains from St Charles to Marseille Vitrolles airport, from where there are flights to many destinations.

European Bike Express (see above) can be used to get back to UK directly from the South of France. Nearest pick-up points are at Orange (25km north of Avignon) or Montpelier (70km west of Arles).

Navigation

Waymarking

From top to bottom: Swiss R1 and French ViaRhôna waymark with EV17 logo; French ViaRhôna waymark; New ViaRhôna waymark with EV17 logo; ViaRhôna V60A waymark in Bouches-du-Rhône

The route follows two nationally designated cycle routes. In Switzerland véloroute R1 (Rhone Route) is followed. This route is well established and waymarking is almost perfect in consistency. In France the route has been designated as ViaRhôna. This route has been in development since 2010 and by 2015, 75 percent of waymarking was complete. Officially the route is designated V60, but this does not appear on waymarks except in Bouches-du-Rhône (Stage 20) where it appears as V60A. While the planning of national cycle tracks is a regional government responsibility, implementation is delegated to départements. Unfortunately provision of dedicated cycle tracks and waymarking varies greatly between départements. Some, notably Isère (Stages 9–10), Gard and Vaucluse (Stages 18–19), have not yet waymarked their parts of the route. The Swiss part of the variant route passing south of Lake Geneva (Stages 5A–6A) is waymarked R46 Tour de Leman, while the French part is mostly unwaymarked. In 2015 the whole route was accepted by the European Cyclists’ Federation as EuroVélo route 17 and EV17 waymarks are being included on new signposts. In the introduction to each stage an indication is given of the predominant waymarks followed.

In France the route sometimes follows local roads. These are numbered as departmental roads (D roads). However the numbering system can be confusing. Responsibility for roads has been devolved from national to local government and responsibility for many former routes nationales (N roads) has been transferred to local départements and renumbered as D roads. As départements have different systems of numbering, D road numbers often change when crossing département boundaries.

| Summary of cycle routes followed | |||

| R1 | Rhone Route | Stages 1–7 | Switzerland |

| R46 | Tour du Léman | Stages 5A–6A | Switzerland |

| VR | ViaRhôna | Stages 7–19 | France |

| V60A | ViaRhôna | Stage 20 | France |

Maps

There are no published maps specifically covering the Rhone cycle route. Kümmerly & Frey publish a series of regional cycle maps that cover the Swiss part of the route (Stages 1–7).

Kümmerly & Frey (1:60,000)

22Berner Oberland Ost, Goms

21Oberwallis

20Bas Valais, Sion

15Gruyère

14Lausanne, Vallée de Joux

17Genève

For the French Stages (7–20) the most suitable maps are regional road and leisure maps published by Michelin and IGN.

Michelin (1:150,000)

328Ain, Haute-Savoie

327Loire, Rhône

333Isère, Savoie

332Drôme, Vaucluse

340Bouches-du-Rhône, Var

IGN (1:100,000)

143Lons-le-Saunier, Genève

150Lyon, Villefranche-sur-Saône

157Grenoble, Montélimar

163Avignon, Nîmes

171Marseille, Avignon

Various online maps are available to download, at a scale of your choice. A strip map of the Swiss stages can be downloaded from www.veloland.ch, while the French stages can be found at www.viarhona.com. Particularly useful is Open Street Map www.openstreetmap.org, which has a cycle route option showing the route in its entirety. This cannot be downloaded directly from OSM but it can through the Viewranger App (for iPhone or Android) without charge.

Guidebooks

Switzerland Mobility and Werd Verlag publish a guide with maps to the Swiss part of the route, available in French or German (not English). La Suisse a Vélo/Veloland Schweiz, volume 1 Route du Rhône/Rhone Route, ISBN 9783859325647. A guide in French to the ViaRhôna by Claude Bandiera is published by Biclou, ISBN 9782351490006.

Most of these maps and guidebooks are available from leading bookshops including Stanfords, London and The Map Shop, Upton upon Severn. Relevant maps are widely available en route.

Accommodation

Hotels, guest houses and bed & breakfast

For most of the route there is a wide variety of accommodation. The stage descriptions identify places known to have accommodation, but are by no means exhaustive. Hotels vary from expensive five-star properties to modest local establishments. Hotels usually offer a full meal service, guest houses do sometimes. Bed and breakfasts, chambres d’hôte in French, generally offer only breakfast. Tourist information offices, which are listed in Appendix D, will usually telephone on your behalf to check availability and make local reservations. After hours, some tourist offices display a sign outside showing local establishments with vacancies. Booking ahead is seldom necessary, except in high season, although it is advisable to start looking for accommodation no later than 4.00pm. Most properties are cycle friendly and will find you a secure overnight place for your pride and joy.

Prices for accommodation in France are similar to, or slightly cheaper than, prices in the UK. Switzerland is significantly more expensive.

Grand Hotel du Lac in Vevey (Stage 5) was the inspiration for a Booker prize winning novel

Youth hostels

There are only nine official youth hostels on or near the route (five Swiss and four French). These are listed in Appendix E. To use a youth hostel you need to be a member of an association affiliated to Hostelling International (YHA in England, SYHA in Scotland). If you are not a member you will be required to join the local association. Rules vary from country to country but generally all hostels accept guests of any age. Rooms vary from single sex dormitories to family rooms of two to six beds. Unlike British hostels, most European hostels do not have self-catering facilities but do provide good value hot meals. Hostels get very busy, particularly during school holidays, and booking is advised through www.hihostels.com. The cities of Lausanne, Geneva, Lyon and Avignon all have privately owned backpacker hostels.

Gîtes d’étape are hostels and rural refuges mainly for walkers. They are mostly found in mountain areas, although there are three near the ViaRhôna at Evian, Culoz and Pont-St Esprit. Details of French gîtes d’étape can be found at www.gites-refuges.com and in Appendix E. Do not confuse these with gîtes de France, which are rural properties rented as weekly holiday homes.

Camping

If you are prepared to carry camping equipment, this is the cheapest way of cycling the Rhone. The stage descriptions identify many official campsites but these are by no means exhaustive. Camping may be possible in other locations with the permission of local landowners.

Food and drink

Where to eat

There are thousands of places where cyclists can eat and drink, varying from snack bars, hot dog stands and local inns to Michelin starred restaurants. Locations of many places to eat are listed in stage descriptions, but these are by no means exhaustive. English language menus are often available in big cities and tourist areas, but are less common in smaller towns and rural locations. Bars seldom serve food, although some offer snacks such as sandwiches, quiche Lorraine or croque-monsieur (a toasted ham and cheese sandwich). Tipping is not expected in Switzerland. In France, since 2008, tips are by law included in restaurant bills and must be passed on to the staff.

When to eat

Breakfast (German Frühstück; French petit déjeuner) is usually continental: breads, jam and a hot drink with the optional addition particularly in Switzerland of cold meats, cheese and a boiled egg. Birchermüesli, made from rolled oats, nuts and dried fruit, is the forerunner of commercially produced muesli.

Traditionally lunch (German Mittagessen, French déjeuner) was the main meal of the day, although this is slowly changing. Service usually ends by 1.30pm and if you arrive later you are unlikely to be served. Historically, French restaurants offered only a number of fixed price two-, three- and four-course meals at a number of price points. These often represent very good value, particularly for lunch if you want a three-course meal. Almost all restaurants nowadays also offer an à la carte menu and one course from this menu is usually enough at lunchtime if you plan an afternoon in the saddle. The most common lunchtime snacks everywhere are sandwiches, salads, quiche and croque-monsieur.

For dinner (German Abendessen, French dîner) a wide variety of cuisine is available. Much of what is available is pan-European and will be easily recognisable. There are, however, national and regional dishes you may wish to try.

What to eat

Fondue made with Swiss cheese

As francophone Switzerland is mainly an agricultural area, regional dishes tend to make use of local produce, particularly vegetables and dairy products. Varieties of cheese include Emmental, Gruyère and Vacherin. The high Alpine valleys provide good conditions for drying hams and bacon. Rösti is finely grated potato, fried and often served with bacon and cheese while raclette is made from grilled slices of cheese drizzled over potatoes and gherkins. The most famous cheese dish is fondue, melted cheese flavoured with wine and used as a dipping sauce. Papet Vaudois is a dish of leeks and potatoes usually served with sausage. For meat, veal sourced from male calves produced by dairy cattle herds, is popular. Geschnetzeltes (veau a la mode Zurich in French) are thin slices of veal in cream and mushroom sauce. The most common fish are trout from mountain streams and zander (often referred to as pike-perch) found in Swiss lakes. As Swiss cooking uses a lot of salt, it is advisable to taste your food before adding any more. Switzerland is rightly famous for its chocolate and the headquarters of Nestlé, the inventors of milk chocolate bars, are passed in Vevey (Stage 5).

French Savoyard cuisine is similar to that of neighbouring regions in Switzerland and many of the same dishes can be found. A local speciality is tartiflette, a casserole of potatoes, bacon lardons and onions covered with melted Reblochon cheese.

ESCOFFIER TO NOUVELLE CUISINE

France is widely regarded as a place where the preparation and presentation of food is central to the country’s culture. Modern-day French cuisine was first codified by Georges Auguste Escoffier in Le Guide Culinaire (1903). Central to Escoffier’s method was the use of light sauces made from stocks and broths to enhance the flavour of the dish in place of heavy sauces that had previously been used to mask the taste of bad meat. French cooking was further refined in the 1960s with the arrival of nouvelle cuisine which sought to simplify techniques, lessen cooking time and preserve natural flavours by changing cooking methods. This was pioneered at La Pyramide in Vienne (Stage 11) and taken up enthusiastically by Paule Bocuse who operates a number of restaurants in Lyon (Stage 10), often described as the world capital of gastronomy.

Local specialities in Lyon include mâchons, morning snacks made from charcuterie accompanied by Beaujolais red wine and formerly eaten by silk workers. Other dishes include rosette de Lyon (cured pork sausage served in chunky slices), salade lyonnaise (lettuce, bacon and poached egg), cervelle de canut (cheese spread made with herbs, shallots, olive oil and vinegar), pommes de terre lyonnaise (potatoes sautéed with onions and parsley) and quenelles de brochet (creamed pike in an egg-based mousse).

Provençale cooking in southern France makes use of local herbs, olives, olive oil and vegetables including tomatoes, peppers, aubergines and garlic. A traditional provençale dish is ratatouille, a vegetable stew of tomatoes, peppers, onions, aubergines and courgettes. Daube Provençale is beef and vegetables stewed in red wine. In the Camargue, local black bulls are sometimes used for the meat in daube. Mediterranean fish are widely used, a typical dish being bouillabaisse fish stew with tomatoes, onions and herbs. Rice is grown in the Camargue; the most northerly place in Europe it can be cultivated.

What to drink

The Rhone flows through some of the greatest wine producing regions of both Switzerland and France. In Switzerland the vineyards of Valais (Stage 3), Chablais (Stage 4) and Lavaux (Stage 5), both in Vaud, and La Côte (Stage 6) near Geneva produce mostly Fendant dry white wine from chasselas grapes and Dôle soft red wine from pinot noir and gamay grapes. Swiss wine is one of Europe’s best-kept secrets as the Swiss consume almost all the production and export very little. Wine by the glass in restaurants is usually priced by the decilitre (1dl = 100ml) and is served in 1dl, 2dl or 5dl carafes. The nearest equivalent to a UK 175ml standard glass is 2dl.

Local wine bottles outside a wine merchant in l’Hermitage (Stage 13)

The French regard themselves as the world’s premier quality wine producing nation and some of the highest quality wines are made in the Rhone valley, particularly at l’Hermitage (Stage 13) and Châteauneuf-du-Pape (Stage 18) both producing full-bodied red wine. Other areas producing AC (appellation contrôlée) quality wines include Seyssel dry white and sparkling wine in Savoy (Stage 7), Côte Rôtie red wine and Condrieu white wine from Viognier grapes (Stage 12) and Tavel and Lirac rosé wine (Stage 19). The greatest quantity of wine, however, comes from 150 AC communes spread throughout the lower valley from Vienne to Avignon (Stages 12–18) known collectively as the Côtes du Rhône and from an even greater number of vineyards in Gard (Stages 18–19) producing VDQS and Vin de Pays wine (less rigorous quality standards, but nevertheless very drinkable and considerably cheaper) mostly from Carignan and Grenache grapes. Listel, the largest producer in France, produces high quality wines from vineyards on the sands of the Petit Camargue, fertilised by bringing mountain sheep down from the hills to graze the vineyards in winter. They are particularly known for Gris de Gris, white wine made from red grape varieties.

Although western Switzerland and southern France are predominantly wine drinking areas, beer consumption is increasing. Main varieties are Blonde (light coloured lager) and Blanche (cloudy slightly sweet tasting beer made from wheat). Pan-European breweries, such as Kronenbourg and Heineken, produce most of the beer, however, there are a growing number of brasserie artisanal local breweries brewing distinct local beers.

All the usual soft drinks (colas, lemonade, fruit juices, mineral waters) are widely available. Local specialities include Rivella, a Swiss drink sweetened with lactose (milk sugars) and available in a number of varieties. The spring from which Evian water (one of the world’s biggest mineral water brands) is sourced is passed on Stage 5A.

Amenities and services

Grocery shops

All cities, towns and larger villages passed through have grocery stores, often supermarkets, and most have pharmacies. Even small villages have boulangeries (bakers), which open early and produce fresh bread throughout the day. Shop opening hours vary and in southern France many shops close in the afternoon between 1.00pm and 4.00pm.

Cycle shops

The route is well provided with cycle shops, most with repair facilities. Locations are listed in the stage descriptions, although this is not exhaustive. Many cycle shops will adjust brakes and gears, or lubricate your chain, while you wait, often not seeking reimbursement for minor repairs. Touring cyclists should not abuse this generosity and always offer to pay, even if this is refused.

Currency and banks

France switched from the French franc to the euro in 2002. In Switzerland the Swiss franc (CHF) is used. This is a very strong currency, which has appreciated noticeably against the euro in recent years making prices in Switzerland relatively high. In places near the Franco/Swiss border it is usually considerably cheaper to eat, drink and sleep in France rather than Switzerland Almost every town has a bank and most have ATM machines, which enable you to make transactions in English. Contact your bank to activate your bankcard for use in Europe.

Telephone and internet

The whole route has mobile phone (German; handy) coverage. Contact your network provider to ensure your phone is enabled for foreign use with the most economic price package. International dialling codes from UK (+44) are:

+41 Switzerland

+33 France

Most hotels, guest houses and hostels make internet access available to guests, usually free but sometimes for a small fee.

Electricity

Voltage is 220v, 50HzAC. Plugs are standard European two-pin round, although a three-pin version (with centre earth pin) is common in Switzerland.

What to take

Clothing and personal items

Even though the route is predominantly downhill, weight should be kept to a minimum. You will need clothes for cycling (shoes, socks, shorts/trousers, shirt, fleece, waterproofs) and clothes for evenings and days-off. The best maxim is two of each, ‘one to wear, one to wash’. Time of year makes a difference as you need more and warmer clothing in April/May and September/October. All of this clothing should be capable of washing en route, and a small tube or bottle of travel wash is useful. A sun-hat and sun glasses are essential, while gloves and a woolly hat are advisable except in high summer.

In addition to your usual toiletries you will need sun cream and lip salve. You should take a simple first-aid kit. If staying in hostels you will need a towel and torch (your cycle light should suffice).

Cycle equipment

Everything you take needs to be carried on your cycle. If overnighting in accommodation, a pair of rear panniers should be sufficient to carry all your clothing and equipment, but if camping, you may also need front panniers. Panniers should be 100 percent watertight. If in doubt, pack everything inside a strong polythene lining bag. Rubble bags, obtainable from builders’ merchants, are ideal for this purpose. A bar-bag is a useful way of carrying items you need to access quickly such as maps, sunglasses, camera, spare tubes, puncture-kit and tools. A transparent map case attached to the top of your bar-bag is an ideal way of displaying maps and guidebook.

Your cycle should be fitted with mudguards and bell, and be capable of carrying water bottles, pump and lights. Many cyclists fit an odometer to measure distances. A basic tool-kit should consist of puncture repair kit, spanners, Allen keys, adjustable spanner, screwdriver, spoke key and chain repair tool. The only essential spares are two spare tubes. On a long cycle ride, sometimes on dusty tracks, your chain will need regular lubrication and you should either carry a can of spray-lube or make regular visits to cycle shops. A good strong lock is advisable.

Safety and emergencies

Weather

The first half of the route is in the continental climate zone, typified by warm dry summers interspersed with short periods of heavy rain and cold winters. Below Lyon the route enters the Mediterranean zone with hot dry summers and mild damp autumns and winters. The greatest rainfall is in autumn and often occurs in heavy downpours. The beginning of Stage 1 is exposed to mountain weather with heavy winter snowfall, which in some years can remain on the ground until June.

The Rhone valley south of Lyon and the Mediterranean coast are subject to the Mistral, a strong cold but dry wind that blows from the north to the south down the valley. It is most common in winter and spring, but can occur at any time of year. Mistral winds often exceed 40kph during the day, but die down at night. As the route in this guide runs north to south, if the Mistral is blowing it will be behind you!

Road safety

Throughout the route, cycling is on the right side of the road. If you have never cycled before on the right you will quickly adapt, but roundabouts may prove challenging. You are most prone to mistakes when setting off each morning. Both Switzerland and France are very cycle-friendly countries. Drivers will normally give you plenty of space when overtaking and often wait behind patiently until space to pass is available.

Much of the route is on dedicated cycle paths, although care is necessary as these are sometimes shared with pedestrians. Use your bell, politely, when approaching pedestrians from behind. Where you are required to cycle on the road there is usually a dedicated cycle lane. Some city and town centres have pedestrian only zones. These restrictions are often only loosely enforced and you may find local residents cycling within them, indeed many zones have signs allowing cycling. Many one-way streets have signs permitting contra-flow cycling.

None of the countries passed through require compulsory wearing of cycle helmets, although their use is recommended. Modern lightweight helmets with improved ventilation have made wearing them more comfortable.

In Switzerland, cycling after drinking alcohol has the same 50mg/100ml limit as drink-driving (English drink-driving limit is 80mg/100ml). If you cycle after drinking and are caught you could be fined and banned from driving and cycling in Switzerland.

Emergencies

In the unlikely event of an accident, the standardised EU and Swiss emergency phone number is 112. The entire route has mobile phone coverage. Provided you have an EHIC card issued by your home country, medical costs of EU and Swiss citizens are covered under reciprocal health insurance agreements, although you may have to pay for an ambulance and claim the cost back through insurance.

Theft

In general the route is safe and the risk of theft very low, particularly in Switzerland. However, you should always lock your cycle and watch your belongings, especially in cities.

Insurance

Travel insurance policies usually cover you when cycle touring but they do not normally cover damage to, or theft of, your bicycle. If you have a household contents policy, this may cover cycle theft, but limits may be less than the real cost of your cycle. Cycle Touring Club (CTC), www.cyclinguk.org.uk, offer a policy tailored for your needs when cycle touring.

If you live in Switzerland and own a bicycle, you need to purchase an annual vélo vignette, a registration sticker that includes compulsory third-party insurance. However, this is not a requirement for short-term visitors.

About this guide

Text and maps

There are 20 stages, each covered by separate maps drawn to a scale of 1:150,000. At this scale it is not practical to cycle the entire route using only these maps, and more detailed maps are advised. However, in Switzerland signposting and waymarking is generally good and, using these combined with the stage descriptions, it should be possible to cycle the Swiss stages without the expense or weight of carrying a large number of other maps. Beware, however, as the route described here does not always exactly follow the waymarked route. GPX files are freely available, to anyone who has bought the book, on the Cicerone website at www.cicerone.co.uk/755/gpx.

All places mentioned in the text are shown bold on the maps. The abbreviation ‘sp’ in the text indicates a signpost. Distances shown are cumulative within each stage. For each city/town/village passed an indication is given of facilities available (accommodation, refreshments, YH, camping, tourist office, cycle shop, station) when the guide was written, and this information is summarised in Appendix B. This list is neither exhaustive nor does it guarantee that establishments are still in business. No attempt has been made to list all such facilities as this would require another book the same size as this one. For full listing of accommodation, contact local tourist offices. Such listings are usually available online. Tourist offices along the route are listed in Appendix D.

While route descriptions were accurate at the time of writing, things do change. Temporary diversions may be necessary to circumnavigate improvement works and permanent diversions to incorporate new sections of cycle track. This is particularly the case in France where parts of the route are classified as ‘provisional’ as work to provide a separate cycle route is planned but has not yet been implemented. Where construction is in progress you may find signs showing recommended diversions, although these are likely to be in French only.

Some alternative routes exist. Where these offer a reasonable variant, usually because they are either shorter or offer a better surface, they are described in the text and shown in blue on the maps.

Language

Apart from Stages 1–2, where Swiss German is spoken, the route is through the Francophone (French speaking) part of Switzerland and France. Throughout this guide the English spelling Rhone is used. In Swiss German the river is known as the Rotten, in French as the Rhône. Place names, and street names are given in appropriate local languages, German for Stages 1–2 and French for the rest of the route. Exceptions are made for Lake Geneva (Lac Léman in French), Geneva (Genève) and Savoy (Savoie); although compound proper nouns (Anthy-sur-Léman, Côte du Rhône, Haute-Savoie, etc) appear in French. See Appendix G for a list of useful French and German words.

The infant Rhone makes its way from the Rhone glacier towards Gletsch (Stage 1)