Читать книгу The Loire Cycle Route - Mike Wells - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

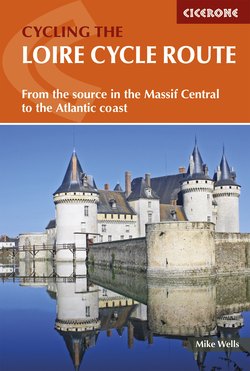

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

To best discover a country you need to travel to its very heart and do so in a way that exposes you to the life going on around you. The River Loire passes through the heart of France and there is no better way of experiencing life in this great country than mounting your bicycle and following this river as it flows from the volcanic landscape of the Massif Central to the Atlantic Ocean. Its length of 1020km makes it the longest river in France. Here you will find a gentler and slower pace of life than in the great cities of Paris, Lyon or Marseille; and although there is some industry, it is less evident in the Loire Valley than alongside France’s other major rivers. Rather this is a land of agriculture and vineyards. The Beauce, north of Orléans, has some of the most fertile arable farmland in the country, while the rolling hills of the Auvergne and Burgundy produce high-quality meat and dairy products. The plains of Anjou grow much of the fruit and vegetables found in the markets and restaurants of Paris, often consumed with wines from premier Loire wine-growing appellations like Muscadet, Sancerre, Pouilly Fumé and Vouvray. All this great food and drink can also be found in restaurants along the route.

Canal Latéral à la Loire at Chavanne (Stage 8)

Most French towns have weekly markets like this one in Vorey (Stage 3)

The Loire is known to the French as the ‘Royal River’ – a name it gets from the Loire Valley’s long association with the kings of France when between the 15th and 17th centuries successive monarchs developed a series of ever more spectacular châteaux. Blois and Amboise were great palaces where the royal court resided to escape political turmoil in Paris. Chambord was a glorious hunting lodge, from where the king would spend long days hunting in the forests of the Sologne, while Chaumont was a home first for the mistress and later the widow of Henri II. The preference of the royal family for life along the Loire stimulated other members of the court to build their own châteaux in the area, resulting in over 50 châteaux recognised as heritage sites by UNESCO beside the Loire and its close tributaries. Although most of these were sequestered, damaged and looted during the French Revolution, 20th-century restoration has breathed new life into them and many can be visited.

Château de Chaumont was the home of King Henri II’s mistress (Stage 18)

In addition to secular buildings, the Loire Valley holds a strong religious presence. Le Puy-en-Velay, with a church and iron Madonna each perched on top of volcanic spires and a great basalt cathedral, is the start point of Europe’s most popular pilgrimage to Santiago in Spain. Tours has both a great cathedral that took so long to build it is in three different styles (Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance) and a basilica built to house the tomb of French patron saint, St Martin, a Roman soldier who became an early bishop of Tours. Other French saints encountered include St Benedict (founder of the Benedictine order), buried at Fleury Abbey in St Benoît, and Ste Bernadette of Lourdes whose preserved body is on display in Nevers. Ste Jeanne d’Arc, a French national heroine who lifted the siege of Orléans and turned the tide of the Hundred Years’ War in favour of France, is widely commemorated particularly in Orléans itself. By contrast, the little village of Germigny-des-Prés has a church from the time of Charlemagne (AD806) that claims to be the oldest in France.

Tours cathedral is a mixture of Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance styles

These châteaux, cathedrals, monasteries, churches and the countryside between them are linked by the Loire Cycle Route. This 1052km route starts beside the river’s source on the slopes of the volcanic plug of Gerbier de Jonc and follows a waymarked route, Vivez la Loire Sauvage, through a series of gorges downhill between the wooded volcanic cones and basalt plateaux of the Auvergne. After leaving the mountains it passes the Charolais hills and at Digoin joins EuroVélo route EV6, which itself joins a French national cycle trail, La Loire à Vélo, near Nevers. This is followed, mostly on level, dedicated cycle tracks, through Orléans, Tours, Angers and Nantes to reach the Atlantic opposite the shipbuilding town of St Nazaire. This is the most popular cycle route in France, followed by thousands of cyclists every year. French regional and départemental governments have invested heavily in infrastructure with well-defined waymarking, asphalt surfaced tracks, dedicated bridges over rivers and underpasses under roads. Almost every town and many large villages have tourist offices that can point you in the direction of (and often book for you) overnight accommodation that varies from five star hotels to village gîtes d’étape.

Background

The Loire passes through the heart of France. Modern France, the Fifth French Republic, is the current manifestation of a great colonial nation that developed out of Charlemagne’s eighth-century Frankish kingdom, eventually spreading its power throughout Europe and beyond.

Roman France

Before the arrival of the Romans in the first century BC, central France was inhabited by Iron Age Celtic tribes like the Gauls. The Romans involved local tribal leaders in government and control of the territory. With improvements in the standard of living, the conquered tribes soon became thoroughly romanised and Gallic settlements became Romano-Gallic towns. During the fourth century AD the Romans came under increasing pressure from Germanic tribes from the east, and by AD401 had withdrawn their legions from central France and the Loire Valley.

The Franks and the foundation of France

After the Romans left there followed a period of tribal settlement. The Franks were a tribe that settled in northern France. From AD496, when Clovis I became their king and established a capital in Paris, the Frankish kingdom expanded by absorbing neighbouring states. After Charlemagne (a Frank, AD768–AD814) temporarily united much of western Europe, only for his Carolingian empire to be split in AD843, the Franks became the dominant regional force. The kingdom of France grew by defeating and absorbing neighbouring duchies. In the Loire basin, Anjou was captured in 1214 and Auvergne was absorbed in 1271.

The Hundred Years’ War

One particular neighbour proved hard to defeat. Ever since Vikings settled in Normandy and around the mouth of the Loire in the ninth century there had been a threat from the west. The Vikings became the Normans, and when in 1066 they annexed England, their power base became larger. For nearly 400 years the Norman kings of England and their Plantagenet successors sought to consolidate and expand their territory in France. The main confrontation was the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) fought between France and an alliance of England and Burgundy. For many years the English and Burgundians had the upper hand, capturing large areas of France. The turning point came in 1429 when a French force led by a 17-year-old girl, Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc), succeeded in lifting the siege of Orléans. By 1453 the English had been driven almost completely out of France, consolidating the French monarchy as the dominant force in the region. When Burgundy (1477) and Brittany (1532) were absorbed, the French king controlled the entire Loire basin.

Rue Jeanne d’Arc leads to Orléans cathedral

The Wars of Religion and the Huguenots

The Protestant Reformation spread to France from Germany and Switzerland in the early 16th century and rapidly took hold, driven by a widespread perception of corruption among Catholic clergy. By mid-century many towns had substantial numbers of Protestant worshippers, known as Huguenots. This sparked violent reaction from devout Catholics led by the Duc de Guise, and between 1562 and 1598 France was convulsed by a series of ferocious wars between religious factions. It is estimated that between two million and four million people died as a result of war, famine and disease. The wars were ended by the Edict of Nantes, which granted substantial rights and freedoms to Protestants. However, this was not the end of the dispute. Continued pressure from Catholic circles gradually reduced these freedoms and in 1685 Louis XIV revoked the Edict. Thankfully this did not provoke renewed fighting, many Huguenots choosing to avoid persecution by emigrating to Protestant countries (particularly Switzerland, Britain and the Netherlands), but it had a very damaging effect on the national economy. Many of the towns passed in the Loire Valley suffered during these wars.

The age of the Kings

For 250 years from 1434, when Charles VII seized the château of Amboise (Stage 18), a succession of kings either lived in or spent a lot of time in their royal residences along the Loire and its nearby tributaries. Amboise became a favoured palace and an escape from the unhealthy climate and political intrigues of Paris for Louis XI (1461–1483) and Charles VIII (1483–1498), who rebuilt the château. Louis XII (1498–1515) ruled from Blois (Stage 17), where he had built the front part of the château. His successor François I (1515–1547) greatly enlarged Blois, although he preferred Amboise, which became his principal royal palace. François also commissioned the totally over-the-top Chambord (Stage 18) as a hunting lodge on the edge of the Sologne. Despite taking 28 years and 1800 men to build, it was used for less than seven weeks before being abandoned as impractical, following which it remained unfurnished and unused for 80 years. After François’s death his widow ruled from Chenonceau as regent for underage François II. When Henri III (1574–1589) was driven from Paris by the Wars of Religion he chose to rule from Blois, as did Henri IV (1589–1610). Louis XIII (1610–1643) returned the court permanently to Paris and gave all the royal châteaux in the Loire Valley to his brother, Gaston d’Orléans, who started to restore Chambord. This restoration was continued by the keen huntsman Louis XIV (1643–1715), who furnished the château only to abandon it again in 1685.

The French Revolution

The ancien régime French kingdom ended in a period of violent revolution (1789–1799). The monarchy was swept away and privileges enjoyed by the nobility and clergy removed. Monasteries and religious institutions were closed while palaces and castles were expropriated by the state. Many were demolished, but some survived, often serving as barracks or prisons. In place of the monarchy a secular republic was established. The revolutionary mantra of liberté, égalité, fraternité is still the motto of modern-day France. Chaos followed the revolution and a reign of terror resulted in an estimated 40,000 deaths, including that of King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette. The west of France (Pays de Loire, Brittany and the Vendée), where resistance to the revolution was greatest, saw the highest number of executions outside of Paris. A coup in 1799 led to military leader Napoleon Bonaparte taking control.

The Duchess of Angoulême’s monument in Florent-le-Vieil commemorates 1000 victims of the French Revolution (Stage 24)

Napoleon Bonaparte

Despite ruling France for only 16 years, Napoleon (1769–1821) had a greater influence on the political and legal structures of the country than any other person. He made peace with the Catholic Church and allowed many exiled aristocrats to return, albeit with limited powers. In 1804 he declared himself Emperor of France and started a series of military campaigns that saw the French gain control briefly of much of western and central Europe. Perhaps the longest lasting Napoleonic reform was the Code Napoléon – a civil legal code that was adopted throughout the conquered territories and remains today at the heart of the European legal system. When he was defeated in 1815 by the combined forces of Britain and Prussia, he was replaced as head of state by a restoration of the monarchy under Louis XVIII, brother of Louis XVI.

French industrialisation

During the 19th century the French economy grew strongly, based on coal, iron and steel and heavy engineering. In the Loire basin, St Étienne (close to Stage 5) developed as a major coal mining centre while the iron works at Fourchambault (Stage 11) became the main producer of rails and girders for the expanding French railway and canal systems. A large overseas empire was created, mostly in Africa, and foreign trade saw Nantes (Stage 25) develop as the main port city on France’s Atlantic coast, with industry built around imported products like sugar and tobacco. More infamously, Nantes was the French centre of the triangular slave trade, supplying ships that took 550,000 slaves from Africa to the Americas. Larger ships that could not reach Nantes led to the development of the port city of St Nazaire (Stage 26) right at the river mouth; this became (and still is) an important shipbuilding centre.

Twentieth-century France

Despite being on the winning side, the French economy was devastated by the First World War and the depression of the 1930s. Invasion by Germany in the Second World War saw the French army retreat south across the Loire. Almost all Loire bridges were destroyed either by the retreating army or by German bombing that also damaged many riverside towns – Gien (Stage 14) being particularly badly hit. Surrender saw France temporarily partitioned, with all of southern France becoming part of Vichy – a nominally independent state that was in reality a puppet government controlled by the Germans. In St Nazaire the occupying Germans built an impregnable submarine pen that was so vigorously defended that the city was the last in France to be liberated.

After the war, France was one of the original signatories to the Treaty of Rome (1957), which established the European Economic Community (EEC) and led to the European Union (EU). Economic growth was strong and the French economy prospered. Political dissent, particularly over colonial policy, led to a new constitution and the establishment of the Fifth Republic under Charles de Gaulle in 1958. Subsequent withdrawal from overseas colonies has led to substantial immigration into metropolitan France from ex-colonies, creating the most ethnically diverse population in Europe. Since the 1970s old heavy industry has almost completely disappeared and been replaced with high-tech industry and employment in the service sector.

Shipping on the river

The Loire is only properly navigable below its junction with the Maine near Angers (Stage 22). Above here the river is classed as sauvage: a wild river with shifting sandbanks, rapids at high water-flow and shallows when the flow is low with no locks or cuts to avoid them. In the past, before railways and roads provided a viable alternative, barges floating downstream took merchandise (mostly coal from St Étienne coalfield) from St Rambert (Stage 5). As river conditions prevented any up-stream navigation, these were one-way trips with the barges being broken up at the end of the voyage. Bi-directional trade was possible up to Roanne (Stage 6) only when river conditions were favourable, but became possible year-round when canals that ran parallel with the river opened at the beginning of the 19th century. Small pleasure craft can still reach Roanne by a mixture of canal and river, but the Villerest dam (built 1984) prevents them going any further. There is no commercial shipping on the river nowadays, although enthusiasts have restored many old wooden Loire barges, some of which are used for commercial fishing, but most for leisure pursuits.

Flat-bottomed barges like this reconstruction at La Charité-sur-Loire (Stage 11) once carried goods downriver

The route

The 1052km Loire Cycle Route starts in the Massif Central mountains of central France, then heads north to Orléans (only 100km south of Paris) before turning west to reach the Atlantic at St Nazaire. En route it passes through the French regions of Rhône-Alpes, Auvergne, Bourgogne (Burgundy), Centre, and Pays de la Loire.

Our route (Stage 1) starts at the Loire source on the slopes of Mont Gerbier de Jonc in the Monts du Vivarais, a northern extension of the Cévennes range. From here the river is followed downhill, threading its way through a series of gorges between the puys (volcanic cones), crater lakes and basalt plateaux of the Massif Central before following a voie verte (rural cycle track) along an old railway line to reach the pilgrimage city of Le Puy-en-Velay (Stage 2). The volcanic landscape continues (Stage 3–4) with the route climbing in and out of the gorges and crossing more basalt plateaux. After Aurec the route crosses the edge of the Monts de Forez (Stage 5) before descending into the Forez basin. A final forested ridge is encountered, an outlier of the Monts de Beaujolais (Stage 6), before the route crosses the Villerest dam to reach Roanne, the end of the mountains and the beginning of navigation in the Loire Valley.

The volcanic plug of Mt Gerbier de Jonc (1551m) rises above the Loire source (Stage 1)

Quiet roads and another voie verte are followed (Stage 7) past the Charolais hills with pastures full of eponymous cream-coloured cattle. At Digoin the route joins the towpath of the Canal Latéral à la Loire, which is followed (Stage 8) most of the way to Bourbon-Lancy. Between here and Decize (Stage 9) there is no dedicated cycle way, so quiet roads are followed through gently rolling hills. After Decize the canal is regained and is followed (Stages 10–13), with a few deviations, all the way to Briare, passing opposite the city of Nevers and below the hilltop wine town of Sancerre. Beyond Briare, the Loire, which has so far flowed north, turns to a north-westerly direction, looping round the Sologne (Stages 14–15), a huge area of forest and lakes that was very popular with French royalty and nobility for the pursuit of hunting. The city of Orléans, the most northerly point reached, was the ancient capital of France and is closely linked with the story of Jeanne d’Arc.

Part of the route follows the towpath of Canal Latéral à la Loire (Stages 8 and 10)

Downstream from Orléans, the Loire is known as the ‘Royal River’, so called because of the large number of royal châteaux in the area built by a succession of monarchs between the 14th and 18th centuries. Between Orléans and Blois (Stages 16–17) the route first skirts the fertile Beauce plain, north of the Loire, then crosses the river to visit the spectacular Château de Chambord in the Forêt de Boulogne. Blois and Amboise (Stages 18–19) both have large city-centre royal châteaux, while the smaller château at Chaumont hosts an annual garden festival. The river is now flowing between low chalk and limestone cliffs, into which many caves have been cut to extract building stone. These nowadays have a variety of uses, including wine cellars and mushroom farms. The basilica in Tours is the burial place of France’s patron saint, St Martin, a Roman soldier who converted to Christianity and became bishop of Tours.

Stage 20 leaves the Loire briefly, following its Cher tributary past the châteaux at Villandry with an immaculately kept 100 hectares of formal gardens and Ussé, inspiration for the story of Sleeping Beauty. There are more riverside cliffs, with the route going underground through the caves of a troglodyte village, and hillside vineyards before Saumur (Stage 21). Entering Anjou, heartland of Norman-English France during the Hundred Years’ War, an excursion can be made to visit its capital, Angers (Stage 22). Stages 23–25 follow the river through the Vendée – an area that provided the greatest level of resistance during the French Revolution – and the Muscadet wine region to reach Nantes, a city that grew rich on profits from the African slave trade. Finally the generally flat coastal plain of Loire-Atlantique is crossed (Stage 26) to reach Brevin-les-Pins, opposite the shipbuilding town of St Nazaire.

Natural environment

Physical geography

The Massif Central mountains are the oldest in France, formed mostly of gneiss and metamorphic schists. When the African and European tectonic plates collided approximately 30 million years ago, pushing up the Alps and raising the eastern edge of the Massif Central, they triggered a series of eruptions that formed a chain of volcanoes in the eastern and central parts of the range. Subsequent erosion and weathering have exposed the central igneous volcanic cores, and these dot the landscape through which the first part of the Loire flows – Gerbier de Jonc being a particularly well formed example. This collision of plates also caused rippling of the landmass to the north, creating a series of calcareous ridges. After leaving the Massif Central, the Loire flows down between these ridges, forming a wide basin with outcrops of chalk and limestone. Where the river has cut down through the ridges, tufa limestone cliffs abut the river and these have been extensively quarried for building stone.

The Loire is a fleuve sauvage (untamed river), the level of water fluctuating greatly between seasons. In summer large sandbanks appear, while in winter riverside meadows are flooded. The river is fed by a number of important tributaries including the Allier, Cher, Indre and Vienne (all of which rise in the Massif Central) and the Loir, Sarthe and Maine which drain the hills of Normandy.

Loire Gorge natural park seen from Chambles (Stage 5)

Wildlife

While a number of small mammals (including rabbits, hares, red squirrels, voles, water rats and weasels) may be seen scuttling across the track, this is not an area inhabited by wild animals – with two exceptions. Large forests close to the river were once reserved for royal hunting parties seeking bears, wolves, wild boar and deer. Bears and wolves were wiped out long ago, but deer and boar are still present.

There is a wide range of birdlife. White swans, geese and many varieties of ducks inhabit the river and its banks. Cruising above, raptors, particularly buzzards and kites, are frequently seen hunting small mammals. Birds that live by fishing include cormorants, noticeable when perched on rocks with their wings spread out to dry, and grey herons, which can be seen standing in shallow water waiting to strike or stalking purposefully along the banks. Egrets are commonly seen in fields where they often pick fleas off cattle. Seasonal sandbanks and islands in the Loire attract millions of migratory birds during summer months and some have become protected reserves.

Roe deer crossing the cycle track near Avaray (Stage 17)

Preparation

When to go

With the exception of Stage 1 in the Massif Central, where snow can remain on the ground until late April, the route is generally cycleable from April to October. If the source is inaccessible, an alternative would be to start from the beginning of Stage 3 in Le Puy-en-Velay, which can be reached directly by train.

How long will it take?

The route has been broken into 26 stages, averaging 40km per stage. A fit cyclist, cycling an average of 80km/day should be able to complete the route in under a fortnight. Travelling at a gentler pace of 50km/day and allowing time for sightseeing, cycling the Loire to the Atlantic coast would take three weeks. There are many places to stay along the route, making it is easy to tailor daily distances to your requirements.

What kind of cycle is suitable?

Most of the route is on asphalt cycle tracks or alongside quiet country roads. However, there are some stretches with gravel surfaces and although these are invariably well graded, posing no problems for most kinds of cycle, cycling the Loire is not recommended for narrow-tyred racing cycles. The most suitable type of cycle is either a touring cycle or a hybrid (a lightweight but strong cross between a touring cycle and a mountain bike with at least 21 gears). There is no advantage in using a mountain bike. Front suspension is beneficial as it absorbs much of the vibration. Straight handlebars, with bar-ends enabling you to vary your position regularly, are recommended. Make sure your cycle is serviced and lubricated before you start – particularly the brakes, gears and chain.

As important as the cycle is your choice of tyres. Slick road tyres are not suitable and knobbly mountain bike tyres not necessary. What you need is something in-between with good tread and a slightly wider profile than you would use for everyday cycling at home. To reduce the chance of punctures, choose tyres with puncture-resistant armouring, such as a Kevlar™ band.

Fully equipped cycle and free air for cyclists in Savonnières (Stage 20)

Getting there and back

By rail

The start of the route on the slopes of Gerbier de Jonc is not directly accessible by public transport. There are railway stations east of the start at Livron in the Rhone Valley (82km away with 1331m ascent) and west of the start at Langogne (51km with 825m ascent). In addition there is a narrow gauge line that runs from Tournon in the Rhone Valley to Lamastre, from where it is 51km to the start with 1288m ascent. Although this is nearer to the start than Livron, financial problems in recent years have curtailed most services on this line and it no longer provides a suitable alternative.

All these options require long rides with substantial amounts of ascent. The average cyclist should set aside a day to reach Gerbier de Jonc from any of these points. There is, however, a bus service from Valence bus station in the Rhone Valley that runs up to Le Cheylard more than halfway along the route from Livron. From Le Cheylard it is 31km to the start with 989m ascent. Buses on route 12 that carry cycles run three times daily (mid-morning, early afternoon and late afternoon) Monday to Saturday from 1 April until 30 November, with a journey time of 90 minutes. There is one Sunday journey (early evening). Details can be found at www.lesept.fr; for booking tel +33 4 75 29 11 15. The routes to the source from Le Cheylard and Langogne are described in detail in the Prologue.

Valence Ville station is on the old Rhone Valley main line between Lyon and Marseille and is served by hourly trains from Lyon Part Dieu or every two hours from Marseille St Charles. Note that Valence TGV station is 10km NE of Valence, with a connecting service linking it to Valence Ville. Langogne is served by trains between Clermont-Ferrand and Nîmes, but there are only three services per day on this line.

If travelling from the UK, you can take your cycle on Eurostar from London St Pancras (not Ebbsfleet nor Ashford) to Paris (Gare du Nord). Trains between London and Paris run hourly throughout the day, taking less than two and a half hours. Cycles booked in advance travel in dedicated cycle spaces in the baggage compartment of the same train as you. Bookings, which cost £30 single, can be made through Eurostar baggage (tel 0344 822 5822). Cycles must be checked in at St Pancras Eurostar luggage office (beside the bus drop-off point) at least 40 minutes before departure. There is no requirement to package or dismantle your cycle. More information can be found at www.eurostar.com. Unfortunately the daily direct Eurostar service to Lyon, Valence and Marseille does not carry cycles.

CROSSING PARIS

After arrival in Paris you need to cycle from Gare du Nord to Gare de Lyon following a series of grands boulevards (wide avenues) on an almost straight 4km route. Go ahead opposite the main entrance to Gare du Nord along semi-pedestrianised Bvd de Denain. At the end turn L (Bvd de Magenta) and follow this to reach Place de la République. Continue round this square and leave on the opposite side by Bvd du Temple, becoming Bvd des Filles du Calvaire then Bvd Beaumarchais, to reach Place de la Bastille. Bear L (passing memorial column to 1830 revolution) and R (passing Opéra Bastille L) into Rue de Lyon, to reach Gare de Lyon station.

TGV Sud-Est high-speed trains run from Paris (Gare de Lyon) to Lyon and on to Marseille. Most trains on this route, particularly those serving Marseille, do not carry cycles; however, there are a few services each day which call at Lyon, Valence and Avignon that have a limited amount of cycle accommodation with mandatory reservation (€10). Details can be found and bookings made at the SNCF (French Railways) website, www.voyages-sncf.com

Provision of cycle space on European trains is steadily increasing, and up-to-date information on travelling by train with a bicycle can be found at a website dedicated to worldwide rail travel, ‘The man in seat 61’: www.seat61.com

By air

Airports at Lyon (three trains daily taking 30 minutes to Valence Ville), and Marseille (hourly service taking 2 hours to Valence Ville or three trains daily taking 4–5 hours to Langogne via Nîmes), both served by a variety of international airlines, can be used to access the Loire source. Airlines have different requirements regarding how cycles are presented and some, but not all, make a charge, which you should pay when booking as it is usually greater at the airport. All require tyres partially deflated, handlebars turned and pedals removed (loosen pedals beforehand to make them easier to remove at the airport). Most will accept your cycle in a transparent polythene bike-bag, although some insist on use of a cardboard bike-box. Excess Baggage Company counters at Heathrow and Gatwick sell cardboard bike boxes (www.left-baggage.co.uk). Away from the airports, boxes can be obtained from cycle shops, sometimes for free. You do however have the problem of how to get the box to the airport.

By road

If you’re lucky enough to have someone prepared to drive you to the start, Gerbier de Jonc is on the D378 close to its junction with D116 and D237 in the Ardèche département of France (44˚50’29”N, 04˚13’08”E; 31T 596317E, 4966063N). With your own vehicle the most convenient place to leave it is Tours, from where trains can be used to reach Valence or Langogne on the outward journey, and which can be reached by train from St Nazaire on the return. Tours is about 525km from Calais.

European Bike Express operates a coach service with dedicated cycle trailer from Northern England, picking up en route across England to the Mediterranean, with a drop-off point at Valence. Details and booking through www.bike-express.co.uk

Intermediate access

There are international airports at St Étienne (Stage 5), Tours (Stage 18) and Nantes (Stage 24). After St Étienne much of the route is closely followed by railway lines; stations en route are listed in the text. From mid June to mid September SNCF run Interloire cycle trains daily between Orléans and Le Croisic (west of St Nazaire). These have enhanced capacity for cycles, at no extra charge, and call at Blois, St Pierre-des-Corps (for Tours), Saumur, Angers, Ancenis, Nantes and St Nazaire. Find details at www.loire-a-velo.fr

Loading cycles on the Interloire cycle train at St Nazaire (Stage 26)

Getting home

The nearest station to St Brevin-les-Pins is in St Nazaire, 9km away on the opposite side of the Loire estuary. Details on how to reach the station are given at the end of Stage 26. TGV Atlantique services, some of which carry cycles, run from St Nazaire to Paris Montparnasse station, sometimes requiring a change in Nantes. It is then necessary to cycle through the middle of Paris to reach Gare du Nord and catch a Eurostar train to London. Cycle check-in at Gare du Nord is at the Geoparts office (follow the path to the left of platform 3) at least 1 hour before departure.

Alternatively, you can travel by regional trains that carry cycles to St Malo (via Nantes and Rennes), from where daily ferry services sail to Portsmouth (Brittany Ferries, www.brittany-ferries.co.uk) and Poole via the Channel Islands (Condor Ferries, www.condorferries.co.uk).

Navigation

Maps

There is no specific cycling map that covers the whole route. From the source to Digoin (Stages 1–7) it is necessary to rely on the maps in this book or use general road and leisure maps. The most suitable road maps are:

Michelin (1:150,000)

331 Ardèche, Haute Loire

327 Loire, Rhône

IGN (1:100,000)

156 Le Puy-en-Velay, Privas

149 Lyon, St Étienne

141 Moulins, Vichy

Below Digoin (Stage 8 onwards) the route is excellently mapped by the first four sheets of the definitive series of 1:100,000 strip maps of EuroVélo 6, published by Huber Kartographie. These can be purchased separately or as a set of six with two additional maps showing the route of EV6 through eastern France to Basle.

Huber Kartographie, La Loire à Vélo (1:100,000)

sheet 4 Belleville-sur-Loire – Paray-le-Monial

sheet 3 Blois – Belleville-sur-Loire

sheet 2 Angers – Blois

sheet 1 Atlantique – Angers

Various online maps are available to download, at a scale of your choice. Particularly useful is Open Street Map, www.openstreetmap.org, which has a cycle route option showing the routes of both La Loire à Vélo and EV6. There are specific websites dedicated to Loire à Vélo and EV6 which include definitive route maps and details about accommodation and refreshments, points of interest, tourist offices and cycle shops. These can be found at www.cycling-loire.com and www.eurovelo6-france.com

Waymarking

The first four stages from Gerbier de Jonc to Aurec approximately follow a regional cycle route waymarked as ‘Vivez la Loire Sauvage’ (VLS). There is no waymarking between Aurec and Digoin (Stages 5–7). After Digoin, EuroVélo route 6 (EV6) is followed, and at Cuffy near Nevers (Stage 11) this is joined by a French national route waymarked as La Loire à Vélo (LV). Although these two routes then run together to St Brevin-les-Pins opposite St Nazaire, waymarking is predominantly ‘Loire à Vélo’. Route development and waymarking vary between départements. In the introduction to each stage an indication is given of the predominant waymarks followed.

The first part of the route before Nevers often follows local roads. These are numbered as départmental roads (D roads). However, the numbering system can be confusing. Responsibility for roads in France has been devolved from national to local government, with responsibility for many former routes nationales (N roads) being transferred to local départements. This has resulted in most being renumbered as D roads. As départements have different systems of numbering, D road numbers often change when crossing département boundaries.

| Summary of cycle routes followed | ||

| VLS | Vivez la Loire Sauvage | Stages 1–4 |

| EV6 | EuroVélo 6 | Stages 8–10 |

| LV | Loire à Vélo | Stages 11–26 |

Clockwise from top (etc): Vivez la Loire Sauvage waymark; La Loire en Bourgogne waymark; Combined Loire à Vélo and EV6 waymark; Provisional Loire à Vélo waymark

Guidebooks

There are three published guidebooks, but all three only cover Stages 11–26 between Nevers and St Nazaire. Chamina Edition publish La Loire à Vélo in French with strip maps at 1:100,000. Ouest-France publish Loire à Vélo Trail by Michel Bonduelle, originally in French with an English translation first published in 2010. In German, Esterbauer Bikeline publish a Radtourenbuch und Karte (cycle tour guidebook with maps) with maps at 1:75,000.

There are a number of general touring guides to the Loire, including those from Michelin Green Guides (Château of the Loire) and Dorling Kindersley Eyewitness Travel (Loire Valley).

Most of these maps and guidebooks are available from leading bookshops including Stanfords, London and The Map Shop, Upton-upon-Severn. Relevant maps are widely available en route.

Accommodation

Hotels, guest houses and bed & breakfast

For most of the route there is a wide variety of accommodation. The stage descriptions identify places known to have accommodation, but they are not exhaustive. Hotels vary from expensive five-star properties to modest local establishments and usually offer a full meal service. Guest houses and bed & breakfast accommodation, known as chambres d’hôte in French, generally offer only breakfast. Tourist information offices will often telephone for you and make local reservations. After hours, some tourist offices display a sign outside showing local establishments with vacancies. Booking ahead is seldom necessary, except on popular stages in high season, although it is advisable to start looking for accommodation after 1600. Most properties are cycle-friendly and will find you a secure overnight place for your pride and joy. Accueil Vélo (cyclists welcome) is a national quality mark displayed by establishments within 5km of the route that welcome cyclists and provide facilities including overnight cycle storage.

Prices for accommodation in France are similar to, or slightly cheaper than, prices in the UK.

Many hotels and guest houses display Cyclists Welcome signs

Youth hostels and gîtes d’étape

There are five official youth hostels on or near the route and these are listed in Appendix D. In addition there are independent backpackers’ hostels in some of the larger towns and cities. To use an official youth hostel you need to be a member of an association affiliated to Hostelling International (YHA in England, SYHA in Scotland). Unlike British hostels, most European hostels do not have self-catering facilities but do provide good value hot meals. Hostels get very busy, particularly during school holidays, and booking is advised through www.hihostels.com. Details of independent hostels can be found at www.hostelbookers.com

Gîtes d’étape are hostels and rural refuges in France, mainly for walkers. They are mostly found in mountain areas, although there are some along the Loire Valley, particularly in Ardèche. Full details of all French gîtes d’étape can be found at www.gites-refuges.com. Do not confuse these with Gîtes de France, which are rural properties rented as weekly holiday homes.

Most accommodation has secure storage for cycles, like this cycle garage in Gien (Stage 14)

Camping

If you are prepared to carry all the necessary equipment, camping is the cheapest way of cycling the Loire. The stage descriptions identify many official campsites but these are not exhaustive. Camping may be possible in other locations with the permission of local landowners.

Food and drink

Where to eat

There are thousands of places where cyclists can eat and drink, varying from snack bars, crêperies and local inns to Michelin-starred restaurants. Locations of many places to eat are listed in stage descriptions, but these are by no means exhaustive. Days and times of opening vary. When planning your day, try to be flexible, as some inns and small restaurants do not open at lunchtime. An auberge is a local inn offering food and drink. English-language menus may be available in big cities and tourist areas, but are less common in smaller towns and rural locations.

When to eat

Breakfast (petit déjeuner) is usually continental: breads, jam and a hot drink. Traditionally lunch (déjeuner) was the main meal of the day, although this is slowly changing, and is unlikely to prove suitable if you plan an afternoon in the saddle. Most restaurants offer a menu du jour at lunchtime; a three-course set meal that usually offers very good value for money. It is often hard to find light meals/snacks in bars or restaurants, and if you want a light lunch you may need to purchase items such as sandwiches, quiche Lorraine or croque-monsieur (toasted ham and cheese sandwich) from a bakery.

For dinner (dîner) a wide variety of cuisine is available. Much of what is available is pan-European and will be easily recognisable. There are, however, national and regional dishes you may wish to try. Historically, French restaurants offered only fixed-price set menus with two, three or more courses. This is slowly changing and most restaurants nowadays offer both fixed-price and à la carte menus.

What to eat

France is widely regarded as a place where the preparation and presentation of food is central to the country’s culture. Modern-day French cuisine was first codified by Georges Escoffier in Le Guide Culinaire (1903). Central to Escoffier’s method was the use of light sauces made from stocks and broths to enhance the flavour of the dish in place of heavy sauces that had previously been used to mask the taste of bad meat. French cooking was further refined in the 1960s with the arrival of nouvelle cuisine, which sought to simplify techniques, lessen cooking time and preserve natural flavours by changing cooking methods.

By contrast, traditional cooking of the Auvergne is rustic fare, mostly combining cheaper cuts of pork with potatoes and basic vegetables, including soupe aux chou (cabbage, pork and potato soup), potée Auvergnate (hotpot of pork, potatoes and vegetables) and truffade (cheese, garlic and potato pancake). The crisp mountain air of the higher parts of the Auvergne is perfect for drying hams and sausages. One particular speciality is lentilles vertes, green lentils from Le Puy-en-Velay used in soup or served with duck, goose or sausage dishes. Local cheeses include bleu d’Auvergne, Cantal and St Nectaire, while tarte aux myrtilles is a traditional dessert made with bilberries from the mountains.

Burgundy in central France is famous not only for its eponymous red wine but also for beef from Charolais cattle, poultry from Bourg-en-Bresse, mustard from Dijon and cheese made with the milk from Salers cattle. This is reflected in regional cuisine, particularly bœuf Bourguignon (beef slow-cooked in red wine) and coq au vin (chicken casseroled in red wine). Other specialities include escargots à la Bourgogne (snails in garlic and parsley butter) and lapin à la moutarde (rabbit in mustard sauce).

Creamy coloured Charolais cattle graze the Charolais hills (Stage 9)

The food of Pays de la Loire is more elegant, reflecting perhaps the regal history of the region. Freshwater fish (including pike, carp and salmon), often served with beurre blanc (white wine and butter sauce), is plentiful inland, while sea fish and shellfish, particularly oysters, abound near the Atlantic. Châteaubriand steak (a thick cut from the tenderloin filet) is named after a small village. Other meat dishes include rillauds d’Anjou (fried pork belly) and muscatel sausages. Caves in riverside cliffs are widely used to cultivate mushrooms, which appear in many dishes. Desserts include gâteau Pithiviers (puff pastry and almond paste tart). A long history of sugar refining and biscuit making has given Nantes such specialities as berlingot Nantais (multi-coloured pyramid-shaped sugar sweets), shortbreads and Petit Beurre biscuits.

What to drink

The lower and middle Loire Valley hosts a string of wine-producing districts, many producing VDQS and good vin de pays wines, but there are some well-known appellations. Most wine is white but there are some areas producing non-appellation soft red wines from gamay or pinot noir grapes. There is a wide contrast in styles, with dry (often very dry) whites being produced in the east and west while sweeter whites, rosés and softer reds are produced in the central part between Orléans and Angers.

The first appellations encountered are Pouilly and Sancerre, two villages that face each other across the middle Loire (Stage12). Here, sauvignon blanc grapes are used to produce flinty dry white wines recommended to be drunk with shellfish. Further downriver between Amboise and Tours are the Touraine appellation districts of Vouvray and Montlouis (Stage 19) where chenin blanc grapes produce dry, sweet and sparkling white wines. In the districts of Chinon and Bourgueil (Stage 21), cabernet franc grapes are used to make soft Beaujolais-style red wine, usually served chilled. Slightly downriver, Saumur (Stage 21) is a light and fruity red. Anjou wine comes from an area just south of Angers (Stage 23). Here again chenin blanc grapes produce mostly sweet white wine, although the district is best known for rosé wine and vin gris (white wine made from red grapes) using cabernet franc grapes. The largest of the Loire’s wine-producing appellations is that of Muscadet between Ancenis and Nantes (Stages 24–26). Muscadet is the name of a grape, unique to this area, which produces a very dry white wine with low acidity, perfect for serving with fish or seafood.

Particular apéritifs and digestifs from the Loire include yellow gentiane from Auvergne and green verveine du Velay made near Le Puy from verbena. The blackcurrant liqueur Crème de Cassis comes from Burgundy, while orange-flavoured Cointreau is distilled near Angers (Stage 22). Chambord is a blackberry and raspberry liqueur produced in the Loire Valley since 1982, based upon a favourite drink of Louis XIV.

The green verbena-flavoured verveine du Velay liqueur is made in Le Puy-en-Velay

Although central France is predominantly a wine-drinking region, beer (bière) is widely consumed. Draught beer (une pression) is usually available in two main styles: blonde (European style lager) or blanche (partly cloudy wheat beer).

All the usual soft drinks (colas, lemonade, fruit juices, mineral waters) are widely available. In the Auvergne, mineral water naturally filtered through the volcanic rocks of the Massif Central is a major industry with well-known brands including Badoit, Volvic and Vichy.

Amenities and services

Grocery shops

All cities, towns and larger villages passed through have grocery stores, often supermarkets, and most have pharmacies. Almost every village has a boulangerie (bakery) that is open from early morning and bakes fresh bread several times a day. Shop opening hours vary and in southern France many shops close in the afternoon between 1300 and 1600.

Cycle shops

The route is well provided with cycle shops, most with repair facilities. Locations are listed in the stage descriptions, although this is not exhaustive. Many cycle shops will adjust brakes and gears, or lubricate your chain, while you wait, often not seeking reimbursement for minor repairs. Touring cyclists should not abuse this generosity and always offer to pay, even if this is refused.

Currency and banks

France switched from French francs to €uros in 2002. Almost every town has a bank and most have ATM machines which enable you to make transactions in English. However, very few offer over-the-counter currency exchange. In major cities like Orléans, Tours and Nantes, there are commercial exchange bureaux, but in other locations the only way to obtain currency is to use ATM machines to withdraw cash from your personal account. Contact your bank to activate your bank card for use in Europe, or put cash on a travel card for use abroad.

Telephone and internet

The whole route has mobile phone coverage. Contact your network provider to ensure your phone is enabled for foreign use with the optimum price package. The international dialling code from the UK (+44) to France is +33.

Almost all hotels, guest houses and hostels and many restaurants make internet access available to guests, usually free of charge.

Electricity

Voltage is 220v, 50HzAC. Plugs are standard European two-pin round.

What to take

Clothing and personal items

Even though the route is predominantly downhill, weight should be kept to a minimum. You will need clothes for cycling (shoes, socks, shorts/trousers, shirt, fleece, waterproofs) and clothes for evenings and days off. The best maxim is two of each: ‘one to wear, one to wash’. Time of year makes a difference as you need more and warmer clothing in April/May and September/October. All of this clothing should be washable en route, and a small tube or bottle of travel wash is useful. A sun hat and sunglasses are essential, while gloves and a woolly hat are advisable except in high summer.

In addition to your usual toiletries you will need sun cream and lip salve. You should take a simple first-aid kit. If staying in hostels you will need a towel and torch (your cycle light should suffice).

Cycle equipment

Everything you take needs to be carried on your cycle. If overnighting in accommodation, a pair of rear panniers should be sufficient to carry all your clothing and equipment, although if camping, you may also need front panniers. Panniers should be 100% watertight. If in doubt, pack everything inside a strong polythene lining bag. Rubble bags, obtainable from builders’ merchants, are ideal for this purpose. A bar-bag is a useful way of carrying items you need to access quickly such as maps, sunglasses, camera, spare tubes, puncture kit and tools. A transparent map case attached to the top of your bar-bag is an ideal way of displaying maps and guidebook.

Your cycle should be fitted with mudguards and bell, and be capable of carrying water bottles, pump and lights. Many cyclists fit an odometer to measure distances. A basic tool kit should consist of puncture repair kit, spanners, Allen keys, adjustable spanner, screwdriver, spoke key and chain repair tool. The only essential spares are two spare tubes. On a long cycle ride, sometimes on dusty tracks, your chain will need regular lubrication; you should either carry a can of spray-lube or make regular visits to cycle shops. A good strong lock is advisable.

Safety and emergencies

Weather

Stage 1 is exposed to mountain weather with winter snowfall that can remain on the ground until April. The rest of the route is in the cool temperate zone with warm summers, cool winters and year-round moderate rainfall which increases for the last few stages as you near the Atlantic.

Road safety

Throughout the route, cycling is on the right side of the road. If you have never cycled before on the right you will quickly adapt, but roundabouts may prove challenging. You are most prone to mistakes when setting off each morning. France is a very cycle-friendly country; drivers will normally give you plenty of space when overtaking and often wait behind patiently until space to pass is available.

Much of the route is on dedicated cycle paths, although care is necessary as these are sometimes shared with pedestrians. Use your bell, politely, when approaching pedestrians from behind. Where you are required to cycle on the road there is often a dedicated cycle lane.

Many city and town centres have pedestrian-only zones. These restrictions are often only loosely enforced and you may find locals cycling within them – indeed, many zones have signs allowing cycling. One-way streets often have signs permitting contra-flow cycling.

Contra-flow cycling is often permitted in one-way streets

France does not require compulsory wearing of cycle helmets, although their use is recommended. Modern lightweight helmets with improved ventilation have made wearing them more comfortable.

Emergencies

In the unlikely event of an accident, the standardised EU emergency phone number is 112. The entire route has mobile phone coverage. Provided you have a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC) issued by your home country, medical costs of EU citizens are covered under reciprocal health insurance agreements – although you may have to pay for an ambulance and claim the cost back through insurance.

Theft

In general the route is safe and the risk of theft very low. However, you should always lock your cycle and watch your belongings, especially in cities.

Insurance

Travel insurance policies usually cover you when cycle touring, but they do not normally cover damage to, or theft of, your bicycle. If you have a household contents policy, this may cover cycle theft, but limits may be less than the real cost of your cycle. Cycle Touring Club (CTC) offer a policy tailored to the needs of cycle tourists (www.ctc.org.uk).

About this guide

Text and maps

There are 26 stages, each covered by maps drawn to a scale of approximately 1:150,000. These maps have been produced specially for this guide and when combined with the detailed stage descriptions it is possible to follow the route without the expense or weight of carrying a large number of other maps, particularly after Nevers where signposting and waymarking is excellent. Beware, however, as the route described here does not always exactly follow the waymarked route. GPX files are freely available to anyone who has bought this guide on Cicerone’s website at www.cicerone.co.uk/842/gpx

Gradient profiles are provided for Stages 1–6, the hillier part of the route. After Roanne there are few hills and except for an alternative route that goes uphill to Sancerre (Stage 12) no ascents of over 50m are encountered.

Place names on the maps that are significant for route navigation are shown in bold in the text. The abbreviation ‘sp’ in the text indicates a signpost. Distances shown are cumulative within each stage. For each city/town/village passed, an indication is given of facilities available (accommodation, refreshments, YH, camping, tourist office, cycle shop, station) when the guide was written. This information is neither exhaustive nor does it guarantee that establishments are still in business. No attempt has been made to list all such facilities, as this would require another book of the same size. For full listing of accommodation, contact local tourist offices. Such listings are usually available online. Tourist offices along the route are listed in Appendix C.

Although route descriptions were accurate at the time of writing, things do change. Temporary diversions may be necessary to circumnavigate improvement works and permanent diversions to incorporate new sections of cycle track. This is particularly the case between Bourbon-Lancy and Decize (Stage 9) and after Nantes (Stage 26), where much of the route is classified as ‘provisional’ and work to provide a separate cycle route is ongoing. Where construction is in progress you may find signs showing recommended diversions, although these are likely to be in French only. Deviations and temporary routes are waymarked with yellow signs.

Some alternative routes exist. Where these offer a reasonable variant, usually because they are either shorter or offer a better surface, they are mentioned in the text and shown in blue on the maps.

Language

French is spoken throughout the route, although many people – especially in the tourist industry – speak at least a few words of English. In this guide, French names are used with the exception of Bourgogne and Bretagne, where the English Burgundy and Brittany are preferred. The French word château covers a wide variety of buildings, from royal palaces and stately homes to local manor houses and medieval castles. See Appendix F for a glossary of French terms that may be useful along the route.