Читать книгу Cycling London to Paris - Mike Wells - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The City of London skyline has many modernistic buildings (classic route, Stage 1)

Near the northern edge of Western Europe stand two great capital cities, London and Paris, undoubtedly two of the greatest cities in the world. Both were the capitals of worldwide empires that competed for domination around the world. This imperial past is long gone but has resulted in cosmopolitan populations with residents drawn from around the globe. Grand government buildings, important centres of worship and famous museums and galleries line world-renowned streets surrounded by popular parks and gardens. Everything one has, the other claims to match or better: Paris has the Eiffel tower, London has Tower bridge; Paris has Notre Dame cathedral, London St Pauls; Paris has the Louvre, London the National gallery; Paris has the Bois de Boulogne, London the Royal parks; the list is endless.

But these two cities are not isolated phenomena, both being surrounded by attractive countryside with rolling chalk downland, pastoral Wealden valleys and picturesque country towns. There are even two great cathedrals in the land that lies between them: Canterbury (off-route) is the mother church of the Church of England while Amiens (classic route, Stage 7) is the largest cathedral in France. Before the last ice age, which finished about 10,000 years ago, this was one continuous landmass but as the ice melted and sea levels rose the two countries became separated by the English Channel. The opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994 revolutionised travel between London and Paris. Frequent trains now make the journey in less than two and a half hours, speeding between London St Pancras and Paris Gare du Nord at up to 300kmph. Passengers have a brief glimpse of the countryside of south-east England and northern France as they rush past, but no time to explore or savour it.

A compensating breakthrough came in 2012. To celebrate the London Olympics (the choice of venue for which had resurrected old rivalries with a tight contest between the two cities before London was awarded the games) a waymarked cycle route was inaugurated running from centre to centre. Known as the Avenue Verte (Green Avenue) this 387km route uses suburban streets, quiet country roads and cycle tracks along old railway lines to traverse Surrey and Sussex in England and Haute Normandy in France, crossing the English Channel between Newhaven and Dieppe. The route has become popular with cyclists, particularly French cyclists heading for London.

Avenue Verte follows an old railway line from Neufchâtel-en-Bray to Serqueux (Avenue Verte, Stage 5)

However, the Avenue Verte is not the only way of cycling from London to Paris. Traditionally the busiest route has always been via the short ferry link between Dover and Calais, indeed this is the preferred route for British cyclists riding to Paris, many of them undertaking sponsored rides to raise money for charity. This 490km ride (described here as the classic route) is not waymarked as a through journey, but can be ridden following NCN (National Cycle Network) routes through Kent to the English Channel, and then quiet country roads, canal towpaths and dis-used railways across the Pas de Calais and Picardy to reach the Île de France and Paris.

While some cyclists are happy using just one of these routes to travel between London and Paris, making their return journey by Eurostar train or by plane, others seek to complete the round trip as a circular journey going out by one route and returning by the other. This guide provides detailed out and back descriptions for both routes, enabling cyclists to complete the return ride in either direction. Allowing for a few days sightseeing in the destination city, the 877km round trip makes an ideal two-week journey for average cyclists. There are many places to stay overnight in towns and villages along both routes, while places to eat include country pubs in England and village restaurants in France. Surely this is a more rewarding way to travel between London and Paris than flashing past at 300kph in a Eurostar train!

Background

The first residents of the British Isles arrived from continental Europe before the last ice age when Britain was attached to the mainland. They probably followed the downland chalk ridges that run across what is nowadays northern France and south-east England, keeping above the then thickly forested and swampy valleys of rivers like the Medway and Somme. Traces of these routes still exist and are occasionally followed by the classic route in this guide.

Roman civilisation

Samara was the site of Caesar’s winter camp when he conquered Gaul (classic route, Stage 7)

By the time the Romans arrived in the first century BC, rising sea levels had split Britain from continental Europe, with both sides of the English Channel inhabited by Iron Age tribes of Gauls and Celts. Julius Caesar captured Gaul (most of modern France) between 58 and 51BC, but although he visited Britain, Roman occupation of England did not commence until AD43. The Romans involved local tribal leaders in government and control of the territory. With improvements in the standard of living, the conquered tribes soon became thoroughly romanised and tribal settlements became Romano-Gallic or Romano-British towns. Both London and Paris have their roots in the Roman Empire but while Londinium (London) was the capital of Britannia, Lutetia (Paris) was merely a provincial town in Gaul. The Romans built Watling Street, a road that linked the port of Dubris (Dover, the site of the best preserved Roman house in England) with London and the north. The towns of Canterbury and Rochester were built along this road, while Amiens and Beauvais were Roman towns in northern Gaul between Paris and the Channel. During the fourth century AD, the Romans came under increasing pressure from Germanic tribes from the east and by mid-fifth century had withdrawn their legions from both England and France.

Frankish and Anglo-Saxon settlement

After the Romans left there followed a period of tribal settlement. The Franks were a tribe that settled in northern France. From AD496 when Clovis I became their king and established a capital in Paris, the Frankish kingdom expanded by absorbing neighbouring states. After Charlemagne (a Frank, ruled AD768–814) temporarily united much of western Europe, only for his Carolingian empire to be split in AD843, the Franks became the dominant regional force. During the same period, southern England was settled by Saxons (from eastern Germany), with an area of Jutish (from Jutland in Denmark) settlement in Kent.

The Vikings from Scandinavia began migrating to the region in the early-ninth century AD. In France they settled in Normandy, while in England they initially occupied an area in the north known as the Danelaw. In 1015 the Viking king Canute defeated the Anglo-Saxons in southern England and extended Viking rule over the whole country. In 1066, a disputed succession caused the Normans from Normandy led by William the Conqueror to invade England and for the first time since the Romans left, unify England and northern France under one crown.

Rochester castle was a Norman stronghold (classic route, Stage 2)

The Hundred Years’ War

For nearly 500 years the Norman kings of England and their Plantagenet successors sought to consolidate and expand their territory in Britain and France. The main confrontation was the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) fought between France and an alliance of England and Burgundy. For many years the English and Burgundians had the upper hand and success at Crécy in 1346 (classic route, Stage 6) led to the capture of large areas of France. The turning point came in 1429 when a French force led by 17-year-old Jeanne d’Arc (Joan of Arc) succeeded in lifting the siege of Orleans. By 1453 the English had been driven almost completely out of France, consolidating the French monarchy as the dominant force in the region. The last English stronghold at Calais (classic route, Stage 4) fell in 1558.

Religious influences and the rise of Protestantism

The Romans converted to Christianity in AD312 and this became the predominant religion in France. St Augustine brought Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England in AD597, establishing a church at Canterbury which later became the most important cathedral in the country. Following the murder of Thomas Becket (1170), Canterbury became a destination for pilgrims visiting Becket’s grave. Many ventured further, with both English and French pilgrims continuing through France to Rome or Santiago. During the reign of Henry VIII (1509–1547), the Church of England split from the Catholic Church becoming Protestant. While there was a period of religious turmoil, the change stuck and Protestantism became the dominant force.

In France, the country’s biggest Catholic cathedral was built at Amiens in the 13th century (classic route, Stage 7) and an even bigger one started at Beauvais (classic route, Stage 8), but this was never finished. In the early 16th century the Protestant reformation reached France from Germany and Switzerland, rapidly taking hold driven by widespread perception of corruption among Catholic clergy. By mid-century many towns had substantial numbers of Protestant worshippers, known as Huguenots. This sparked violent reaction from devout Catholics led by the Duc de Guise and between 1562 and 1598 France was convulsed by a series of ferocious wars between religious factions. It is estimated that between two million and four million people died as a result of war, famine and disease. The wars were ended by the Edict of Nantes which granted substantial rights and freedoms to Protestants. However, this was not the end of the dispute. Continued pressure from Catholic circles gradually reduced these freedoms and in 1685 Louis XIV revoked the edict. Thankfully this did not provoke renewed fighting, many Huguenots choosing to avoid persecution by emigrating to Protestant countries (particularly Switzerland, Britain and the Netherlands), but it had a damaging effect on the economy.

The French Revolution

Both France and England were monarchies, although French kings ruled with more autocratic powers than English ones. This led eventually to violent revolution (1789–1799) which ended the ancien régime in France. The monarchy was swept away and privileges enjoyed by the nobility and clergy removed. Monasteries and religious institutions were closed while palaces and castles were expropriated by the state. Many were demolished, but some survived, often serving as barracks or prisons. In place of the monarchy a secular republic was established. The revolutionary mantra ‘liberté, égalité, fraternité’ is still the motto of modern day France. Chaos followed the revolution and a reign of terror resulted in an estimated 40,000 deaths, including King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette. The English novelist Charles Dickens described this period in A Tale of Two Cities:’it was the best of times, it was the worst of times’. A coup in 1799 led to military leader Napoleon Bonaparte taking control.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Despite ruling France for only 16 years, Napoleon (1769–1821) had a greater influence on the political and legal structures of the country than any other person. He made peace with the Catholic Church and allowed many exiled aristocrats to return, although with limited powers. In 1804, he declared himself Emperor of France and started a series of military campaigns which saw the French briefly gain control of much of western and central Europe. Feeling threatened by French aggression, Britain went to war with France. A legacy from this period can be found all along the south-east coast of England (classic route, Stage 3 and Avenue Verte, Stage 3) in the form of Martello towers, small defensive forts built to defend against French invasion. Napoleon was defeated in 1815 by the combined forces of Britain and Prussia, this being the last war between the British and French.

Napoleon is buried under the dome of Les Invalides in Paris (classic route, Stage 11)

Agricultural and industrial revolutions

In Britain, political stability and an entrepreneurial environment allowed industry to develop and grow, fermenting the late 18th-century industrial revolution. Agricultural mechanisation caused millions of workers to leave the land and take jobs in factories producing textiles and iron goods which were distributed by a network of canals and railways and exported by a growing merchant fleet. This industrialisation was primarily in the north, with agriculture continuing to dominate the downland and Wealden valleys of south-east England. Indeed, the pre-19th-century iron industry in the Sussex Weald was unable to compete and ceased to exist.

French industrialisation came later, but by the mid-19th century the French economy was growing strongly based upon coal, iron and steel, textiles and heavy engineering. Coalfields developed in the Nord-Pas de Calais region and textile mills could be found across northern France.

Twentieth-century wars

The fields of northern France were the scene of much fighting during the First World War (1914–1918), with British and French armies engaged for over four years in trench warfare against an invading German army. The frontline lay east of the classic route, with some of the heaviest fighting in the Somme valley near Amiens (classic route, Stage 7). Despite being on the winning side, the French economy was devastated by the war and the depression of the 1930s. Invasion by Germany in the Second World War (1939–1945) led the French army to surrender and the British army to retreat across the Channel, with the Germans occupying northern France for four years. Defensive works spread along Britain’s south coast to defend against an expected German attack that never materialised. An allied invasion of France through Normandy (1944) lifted this occupation with Paris being liberated on 25 August.

European integration

After the war, France was one of the original signatories to the Treaty of Rome (1957) which established the European Economic Community (EEC) and led to the European Union (EU). Economic growth was strong and the French economy prospered. Political dissent, particularly over colonial policy, led to a new constitution and the establishment of the Fifth Republic under Charles de Gaulle in 1958. Subsequent withdrawal from overseas possessions has led to substantial immigration into metropolitan France from ex-colonies, creating the most ethnically diverse population in Europe. Since the 1970s, old heavy industry has almost completely disappeared and been replaced with high-tech industry and employment in the service sector.

Although not joining the EU until 1973 (and planning to leave in 2019), Britain’s post-war path has been remarkably like that of France. Withdrawal from empire in the 1960s and a movement of people from former colonies has made London almost as cosmopolitan as Paris. Heavy industry has been replaced by light industry and services with London becoming the biggest financial centre in Europe. New and developing towns at Crawley (Avenue Verte, Stage 2) and Ashford (classic route, Stage 2) have attracted light industry.

Tower bridge opens to allow ships into the pool of London (classic route, Stage 1)

The routes

Classic route

Historically this route started in Southwark at the southern end of London bridge and used the old Roman Watling Street (A2 in the British road numbering system) to reach Dover. It then followed Route National 1 (N1), a road created during Napoleonic times, from Calais to Paris where it ended at point zero, a bronze plaque set in the pavement in front of Notre Dame cathedral. Modern day traffic conditions have seen these roads change in character and the original route is nowadays not suitable for a leisurely cycle ride. In England, much of the A2 has been improved with up to four lanes of fast moving traffic in each direction, while in France the completion of the autoroute (motorway) network and transfer of responsibility for non-motorway roads from national to local government has led to a downgrading and renumbering of N1 to D901. Despite this, the largely unimproved D901 is a dangerous road with fast moving traffic.

To avoid these problems, this guide describes a route using mostly quiet country roads and rural tracks. It tries, wherever possible, to follow established cycle friendly routes with either separate cycle tracks or cycle lanes marked on the road, but there are a few short stretches on main roads. The geology of south-east England and northern France are similar with successive bands of chalk downland separated by river valleys at right angles to the direction of travel. The route attempts to minimise ascents, although some short climbs are inevitable.

There are a number of off-road sections. Most of these are well-surfaced with either 100 per cent asphalt or a mixture of asphalt and good quality gravel surfaces, usually on old railway trackbeds or along canal towpaths, and present no difficulties for cyclists. Two are rougher and are not suitable for bikes with smooth tyres. The 28km Pilgrims’ Way in England (classic route, Stage 2) follows an ancient track along the North Downs. While this is part of the national cycle network, its use by agricultural vehicles can cause deep ruts to develop and it can be difficult to traverse in wet weather. The 30km Coulée Verte in France (classic route, Stage 8) follows the route of an unsurfaced old railway line. In a dry period it is an easy ride, but during wet weather it becomes soft and muddy making it difficult to traverse. An alternative road route is described to avoid this part of Stage 8.

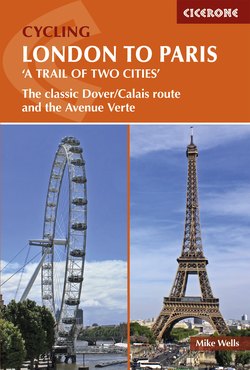

The cycled route runs from the Tower of London to the Eiffel Tower in Paris, giving a ‘tower-to-tower’ distance of 490km (excluding Channel crossing). In London, a network of cycle super-highways (dedicated cycle lanes alongside major roads) is under construction and one of these (CS4) is planned from London Bridge to Woolwich. While this was still in the planning stage as this guide was being written, the beginning of Stage 1 from Tower Bridge Road to Woolwich follows the proposed super-highway. After Woolwich, a waymarked local cycle route (LCN18, part of the London Cycle Network) winds through suburban streets to the edge of Greater London where NCN1 (part of the British National Cycle Network) is joined and followed on dedicated cycle tracks parallel with the busy A2/M2 motorway to reach the Medway at Rochester. Stage 2 uses rural tracks to climb over the North Downs and then joins a cycle track following the ancient Pilgrims’ Way along the shoulder of the downs to Ashford. After a short ride the route reaches the English Channel coast and this is followed (Stage 3) through Folkestone (where an alternative route links with the Channel Tunnel terminal) then climbs over the iconic white cliffs to reach Dover ferry port.

Chantilly château was built in the 19th century after the original building was destroyed during the revolution (classic route, Stage 9)

After crossing the Channel, Stages 4–6 follow a canal and disused railway across the coastal plain, then undulate on minor roads through downland, climbing in and out of a series of pretty valleys, to reach the river Somme at Abbeville. After a flat stage (Stage 7) following the towpath of the canalised Somme to Amiens, the Coulée Verte track along another old railway is followed (Stage 8) up the Selle valley and over more downland before descending to Beauvais. To avoid more hills that lie across the route to Paris, Stage 9 turns south-east down the Thérain valley to Chantilly and then climbs over one last ridge (Stage 10) to reach the Paris Basin. Most, but not all, of Stage 11 through Greater Paris to the Eiffel Tower is on cycle tracks. If you wish to end at point zero, an alternative route described under Avenue Verte Stage 9 takes you to Notre Dame cathedral.

Avenue Verte

To celebrate the 2012 Olympics in London, cycling organisations in Britain and France developed a new cycle route between the London Eye and Notre Dame in Paris. They chose a route which crossed the Channel between Newhaven and Dieppe. Although this gives a longer and less frequent crossing, the 387km cycled is just over 100km shorter than the classic route. The route was designed to make maximum use of Sustrans off-road cycle tracks in England and voies vertes (rural cycle routes) in France, which resulted in long stretches along disused railway track beds in both countries. Most of the route is complete, although in England part of the route following the Cuckoo Trail in Kent (Stage 3) has proved difficult to realise due to land ownership problems, while in France the Forges-les-Eaux–Gisors sector (Stages 5–6) became unavailable when a previously closed railway was reopened and the route now follows local roads over chalk downland to by-pass this problem.

When inaugurated, the route out of London (Stage 1) followed city streets to reach the Wandle Trail. Since then a cycle super-highway (CS7) has been built between central London and Merton and the route described follows this to join the Wandle Trail rather than the more complicated waymarked route. Quiet roads are then used to leave London and climb over the North Downs into the Sussex Weald. After passing Gatwick airport, Stage 2 follows a disused railway east along the mid-Wealden ridge then turns south again (Stage 3) along another disused railway. Minor roads are taken through a gap in the South Downs to the port of Newhaven.

Once in France, a disused railway trackbed takes the route (Stages 4–5) from near Dieppe through the Bray (the French Weald) to Forges-les-Eaux then undulates over downland (Stage 6) before dropping into the Epte valley at Gisors. Another old railway (Stage 7) and a climb onto the Vexin plateau bring the route to the new town of Cergy-Pontoise on the edge of the Paris basin. Stage 8 crosses St Germain forest then follows river and canalside towpaths and city streets into Paris. The final leg (Stage 9) uses more canal towpaths and city streets to reach Notre Dame cathedral in the heart of the city.

Much of the route across the Vexin plateau is on gravel cycle tracks (Avenue Verte, Stage 7)

Natural environment

Physical geography

Prior to the last ice age, south-east England and Northern France were part of the same landmass and as a result share the same geological structure. After the ice age, sea levels rose cutting England off from continental Europe but leaving a series of chalk and limestone anticlinal ridges and clay and gravel filled synclinal depressions that cross both countries from west to east. These are a result of compression caused approximately 30 million years ago when the African and European tectonic plates collided and pushed up the Alps. Where erosion has removed the upper layers between ridges this has revealed sandstone bedrock (Mid-Wealden ridge in England) and created fertile agricultural land known as the Weald in England and the Bray in France. At the northern and southern ends of the route, both London and Paris sit in artesian basins bounded by chalk downland or limestone plateaux.

On both sides of the Channel rivers flow through the valleys between the ridges; including the Medway and Stour in England and the Canche, Somme, Oise and Epte in France. These valleys are mostly filled with tertiary deposits and have been extensively quarried for aggregates leaving large areas of water-filled gravel pits.

Wildlife

While several small mammals and reptiles (including rabbits, hares, squirrels, voles, water rats and snakes) may be seen scuttling across the track, this is not an area inhabited by larger animals with a few exceptions. Foxes are common in England, particularly in London where they can be seen foraging even by day, while many of the forests passed through have roe deer, fallow deer or muntjac populations. Boar can be found in French forests and there are some in south-east England although these are rarely seen. Badgers are common, but as nocturnal animals are unlikely to be encountered.

Preparation

Sauf cyclistes (cyclists excepted) shows contra-flow cycling allowed on a one-way street

When to go

The routes can be cycled at any time of year, but they are best followed between April and October when the days are longer, the weather is warmer and there is no chance of snow.

How long will it take?

Both routes have been broken into stages averaging just under 50km per stage. A summary of stage distances can be found in the route summary tables. A fit cyclist, cycling an average of 80km per day should be able to complete the eleven stages of the classic route in six days and the nine stages of Avenue Verte in five days. Allowing time for exploring Paris, the round trip can be accomplished in two weeks. A faster cyclist averaging 100km per day could complete the round trip in nine days, whereas those preferring a more leisurely pace of 60km per day would take about 17 days. There are many places to stay along both routes making it possible to tailor daily distances to your requirements.

What kind of cycle is suitable?

Most of the route is on asphalt cycle tracks or along quiet country roads. However, there are some stretches with gravel surfaces and, although most are well graded, there are some rougher sections, particularly on the Pilgrims’ Way (classic route, Stage 2) and Coulée Verte (classic route, Stage 8), which are not passable on a narrow tyred racing cycle. The most suitable type of cycle is either a touring cycle or a hybrid (a lightweight but strong cross between a touring cycle and a mountain bike with at least 21 gears). Except for the off-road Coulée Verte (classic route, Stage 8, which has an on-road alternative), there is no advantage in using a mountain bike. Front suspension is beneficial as it absorbs much of the vibration. Straight handlebars, with bar-ends enabling you to vary your position regularly, are recommended. Make sure your cycle is serviced and lubricated before you start, particularly the brakes, gears and chain.

As important as the cycle, is your choice of tyres. Slick road tyres are not suitable and knobbly mountain bike tyres not necessary. What you need is something in-between with good tread and a slightly wider profile than you would use for everyday cycling at home. To reduce the chance of punctures, choose tyres with puncture resistant armouring, such as a Kevlar™ band.

Getting there and back

The start and end points in London and Paris are in city centre locations. Regular fast Eurostar trains connect London St Pancras and Paris Gare du Nord stations enabling you to start or end your ride in either city. See Appendix D for a list of useful transport details.

| UK Nat Grid | Geographic | UTM | |

| Tower Hill | TQ336807 | 00º04’35’’W, 51º30’35’’N | 30U 700031E, 5709709N |

| London Eye | TQ307799 | 00º07’04’’W, 51º30’11’’N | 30U 702873E, 5710563N |

| St Pancras | TQ300832 | 00º07’38’’W, 51º32’00’’N | 30U 699243E, 5713049N |

| Eiffel Tower | 02º17’39’’W, 48º51’31’’N | 31U 448228E, 5411979N | |

| Notre Dame | 02º20’56’’W, 48º51’12’’N | 31U 452237E, 5411356N | |

| Gare du Nord | 02º21’17’’W, 48º52’56’’N | 31U 452695E, 5414559N |

Getting to the start

Main line, suburban and overground trains in London carry cycles. On underground trains in central London, cycles are permitted on sub-surface lines (Circle, District, Hammersmith & City, Metropolitan) but not on deep-tube lines (Bakerloo, Central, Jubilee, Northern, Piccadilly, Victoria, Waterloo & City). On all lines prohibitions apply during weekday rush hours.

The Tower of London is in front of Tower Hill underground station served by the Circle and District lines, both of which carry cycles, and is only a short ride from Cannon Street, Fenchurch Street, Liverpool Street and London Bridge railway stations and Aldgate on the Metropolitan line.

The London Eye is on the South Bank of the Thames close to Waterloo station. Although main line and suburban trains can be used to reach Waterloo, none of the underground lines that serve the station carry cycles. The nearest cycle-permitted underground stations are both on the other side of the river: Westminster (cycle over Westminster bridge and turn left into Belvedere Road) and Embankment (take your cycle by lift to the walkway beside Hungerford railway bridge and walk it over the river). Both these stations are served by the Circle and District lines.

St Pancras Eurostar station is served by Circle, Hammersmith & City and Metropolitan lines which carry cycles (and Northern, Piccadilly and Victoria lines which do not). It is also served by main line and suburban trains at Kings Cross and St Pancras stations and is only a short ride from Euston (main line, suburban and overground services).

Crossing the Channel

Up to 40 ferry sailings per day connect Dover and Calais (classic route, Stages 3–4)

The classic route crosses the English Channel at its narrowest point between Dover or Folkestone in England and Calais in France. There are two ways of making this crossing, by ferry from Dover or by shuttle train through the Channel Tunnel.

Up to 40 ferry sailings operate daily (depending on the season) between Dover Eastern docks and Calais Gare Maritime ferry port operated by two companies, P&O (www.poferries.com) and DFDS (www.dfdsseaways.co.uk). Crossing time is 90 minutes. As these are vehicular ferries there is ample capacity on board for cyclists without the need for reservations, although lower prices are available by advance booking online.

Although up to four vehicle shuttles run every hour through the Channel Tunnel between Cheriton terminal near Folkestone and Coquelles near Calais, only two departures daily carry cycles. These are transported in a specially contracted vehicle, equipped to carry six cycles, which picks up from Cheriton Holiday Inn hotel at 0800 and 1530 and deposits you opposite the CIFFCO building near the Coquelles terminal. Return journeys pick-up in Coquelles at 1230 and 1800. Reservations must be made at least 48 hours in advance on +44 1303 282201. This service is provided as a requirement in Eurotunnel’s operating license and is heavily subsidised, but as it is not promoted by the company it is little used. For more information see www.eurotunnel.com. Directions to Cheriton and Coquelles are given in Stages 3 and 4 of the classic route.

The Channel Tunnel cycle shuttle is slightly cheaper and slightly faster than the ferries and saves 17km of cycling from Folkestone to Dover. However, as this must be booked in advance with only two services per day it is considerably less flexible than the Dover ferries which run frequently throughout the day and night, providing a turn-up-and-go service.

The Avenue Verte crosses the Channel using a ferry operated by DFDS between Newhaven and Dieppe. There are two or three sailings daily depending upon season, which take four hours. Reservations are not normally needed for cycles, although as prices vary between sailings advance booking may enable you to obtain the best price.

Intermediate access

There are international airports at Gatwick (Avenue Verte, Stage 2) and Beauvais (classic route, Stage 8). The English part of the classic route (Stages 1–3) and the first half of Avenue Verte as far as Three Bridges (Stages 1–2) are closely followed by railway lines, as are Stages 7 and 9 of the classic route (Abbeville–Amiens and Beauvais–Chantilly) in France. Stations en route are listed in the text. Between Serqueux–Gisors (Avenue Verte, Stages 5–6) a previously closed railway has been reinstated for freight trains and a limited passenger service has started, but only a few stations have reopened.

Getting home

High-speed Eurostar trains cover the distance from London to Paris in under two and a half hours

This book hopes to encourage you to cycle home by using a different route to that taken on your outward journey. However, if time is at a premium or you are too exhausted to cycle back, it is possible to return by public transport.

The easiest way to return home from Paris to London with your cycle is by train. Eurostar services that take under two and a half hours run approximately hourly throughout the day between Paris Gare du Nord–London St Pancras using the Channel Tunnel. Cycles booked in advance travel in dedicated cycle spaces in the baggage compartment of the same train as you. Bookings, which open six months in advance and cost £30 single, can be made through Eurodespatch (tel +44 344 822 5822) in London or Geoparts (tel +33 1 55 31 58 33) in Paris. Cycles must be checked in at Geoparts luggage office in Gare du Nord (follow path to L of platform 3) at least 60 minutes before departure. There are two dedicated places per train for fully assembled cycles and four more places for dis-assembled cycles packed in a special fibre-glass box. These boxes are provided by Eurostar at the despatch counter, along with tools and packing advice. Leave yourself plenty of time to dismantle and pack your bike. After arrival in St Pancras cycles can be collected from Eurodespatch Centre beside the bus drop-off point at the back of the station. More information can be found at www.eurostar.com.

By air, Paris’s three airports have flights to worldwide destinations, including frequent services to London’s six airports. These are operated by several airlines, the main ones being BA (Charles de Gaulle and Orly to Heathrow), Air France (Charles de Gaulle to Heathrow), EasyJet (Charles de Gaulle to Gatwick, Luton and Southend), Cityjet (Orly to City) and Flybe (Charles de Gaulle to City). These airlines, and Ryanair (who fly from Beauvais, classic route, Stage 8), also operate services to other UK airports. Airlines have different requirements regarding how cycles are presented and some, but not all, make a charge which you should pay when booking as it is usually greater at the airport. All require tyres partially deflated, handlebars turned and pedals removed (loosen pedals beforehand to make them easier to remove at the airport). Most will accept your cycle in a transparent polythene bike-bag, although some insist on use of a cardboard bike-box. These can be obtained from cycle shops, usually for free. You do, however, have the problem of how you get the box to the airport.

Navigation

Waymarking

In England, the classic route follows a series of local and national waymarked cycle trails. In France, the only waymarking is on parts of Stages 4, 7 and 8. Avenue Verte is waymarked throughout, often coinciding with other routes.

The British NCN waymark with AV symbol added; the French Avenue Verte waymark; the French yellow provisional waymark where the final route is still being considered;

Summary of cycle routes followed

| Classic route | ||

| CS4 | Cycle Superhighway 4 | Stage 1 (planned) |

| LCN18 | London Cycle Network 18 | Stage 1 |

| NCN1 | National Cycle Network 1 | Stage 1 |

| NCN177 | National Cycle Network 177 | Stage 1 |

| NCN17 | National Cycle Network 17 | Stage 2 |

| NCN2 | National Cycle Network 2 | Stage 3 |

| V30 | Somme Canalisée towpath | Stage 7 |

| CV | Coulée Verte | Stage 8 |

| N-S | N-S Véloroute | Stage 11 |

| Avenue Verte | ||

| AV | Avenue Verte | Stages 1–9 |

| CS7 | Cycle Superhighway 7 | Stage 1 |

| NCN20 | National Cycle Route 20 | Stages 1–2 |

| NCN21 | National Cycle Route 21 | Stages 1–3 |

| NCN2 | National Cycle Route 2 | Stage 3 |

| V33 | Stage 7 | |

| N-s | N-S Véloroute | Stage 9 |

Both routes in France often follow local roads. These are numbered as départemental roads (D roads). However, the numbering system can be confusing. Responsibility for roads in France has been devolved from national to local government with responsibility for many former routes nationales (N roads) being transferred to local départements. This has resulted in most being renumbered as D roads. As départements have different numbering systems, these D road numbers often change when crossing département boundaries.

Maps

While it is possible to cycle both routes using only the maps in this book (particularly the Avenue Verte which is waymarked throughout), larger scale maps with more detail are available, although these are not specifically cycle maps. Ordnance Survey Landranger 1:50,000 maps give excellent coverage of the English stages while either Michelin or IGN local maps are good for France. Street atlases might be useful for cycling in London and Paris.

| Classic route | Avenue Verte | |

| OS Landranger (1:50,000) | 177 East London | 176 West London |

| 178 Thames Estuary | 187 Dorking & Reigate | |

| 189 Ashford & Romney Marsh | 188 Maidstone & Royal Tunbridge Wells | |

| 179 Canterbury & East Kent | 199 Eastbourne & Hastings | |

| 198 Brighton & Lewes (very small part) | ||

| Michelin (1:150,000) | 301 Pas de Calais, Somme | 304 Eure, Seine-Maritime |

| 305 Oise, Paris, Val d’Oise | 305 Oise, Paris, Val d’Oise | |

| IGN (1:100,000) | 101 Lille/Boulogne-sur-Mer | 107 Rouen/Le Havre (small part) |

| 103 Amiens/Arras | 103 Amiens/Arras | |

| 108 Paris/Rouen | 108 Paris/Rouen |

Various online maps are available to download, at a scale of your choice. Particularly useful is Open Street Map (www.openstreetmap.org) which has a cycle route option showing British NCN routes, French voie verte and the Avenue Verte. The official website for the Avenue Verte is www.avenuevertelondonparis.co.uk which includes definitive route maps, details about accommodation and refreshments, points of interest, tourist offices and cycle shops.

Guidebooks

This is the only guidebook for the classic route and the only one which describes Avenue Verte in both directions. There are two other guidebooks for the Avenue Verte: one in English describing the route from London to Paris (Avenue Verte, published by Sustrans) and one in French for the route from Paris to London (Paris–Londres à vélo, published by Chamina Edition).

There are many guidebooks to London and south-eastern England and to Paris and northern France, including some specially aimed at cyclists. Most of these maps and guidebooks are available from leading bookshops including Stanford’s, London and The Map Shop, Upton upon Severn. See Appendix D for further details. Relevant maps are widely available en route.

Accommodation

For most of the route there is a wide variety of accommodation. The stage descriptions identify places known to have accommodation, but are by no means exhaustive. Prices for accommodation in France are similar to prices in the UK. See Appendix D for a list of relevant contact details.

A former Clunaic abbey overlooks St Leu d’Esserent (classic route, Stage 9)

Hotels, guest houses and B&B

Hotels vary from expensive five-star properties to modest local establishments and usually offer a full meal service. Guest houses and bed and breakfast accommodation, known as chambres d’hôte in French, generally offer only breakfast. Tourist information offices (see Appendix B) will often telephone for you and make local reservations. Booking ahead is seldom necessary, except in high season (mid-July to mid-August in France). Most properties are cycle friendly and will find you a secure overnight place for your pride and joy. Accueil Vélo is a French national quality mark displayed by establishments within 5km of the route that welcome cyclists and provide facilities including overnight cycle storage.

An accueil vélos (cyclists welcome) sign shows an establishment that provides facilities for cyclists

Youth hostels and gîtes d’étape

While there are several youth hostels in both London and Paris, there are only three hostels en route (Calais, Montreuil and Amiens; all on the classic route in France) and three just off-route (Medway, Eastbourne and Southease in England). These are listed in Appendix C. English hostels managed by the YHA and FUAJ hostels in France are affiliated to Hostelling International. Other French hostels are managed by BVJ. Unlike British hostels, most European hostels do not have self-catering facilities but do provide good value hot meals. Hostels get very busy, particularly during school holidays, and booking is advised through www.hihostels.com.

Gîtes d’étape are hostels and rural refuges (shelters) in France mainly for walkers. They are mostly found in mountain areas, although there is one at Forges-les-Eaux (Stage 5) on Avenue Verte. Details of French gîtes d’étape can be found at www.gites-refuges.com. Do not confuse these with Gîtes de France which are rural properties rented as weekly holiday homes.

Camping

If you are prepared to carry camping equipment, this will probably be the cheapest way of cycling the route. Stage descriptions identify official campsites. Camping may be possible in other locations with the permission of local landowners.

Food and drink

Where to eat

There are many places where cyclists can eat and drink, varying from snack bars, crêperies, pubs and local inns to Michelin starred restaurants. Locations are listed in stage descriptions, but these are not exhaustive. Days and times of opening vary. When planning your day, try to be flexible as some inns and small restaurants do not open at lunchtime. In France, an auberge is a local inn offering food and drink. English language menus may be available in big cities and tourist areas, but are less common in smaller towns and rural locations.

When to eat

In England, breakfast in hotels, guest houses and B&B is usually a cooked meal while English pubs generally provide a wide variety of light snack and full meal options for both lunch and dinner.

In France, things are a little different. Breakfast (petit déjeuner) is continental: breads, jam and a hot drink. Traditionally lunch (déjeuner) was the main meal of the day, although this is slowly changing, and is unlikely to prove suitable if you plan an afternoon in the saddle. Most French restaurants offer a menu du jour at lunchtime, a three-course set meal that usually offers excellent value for money. It is often hard to find light meals/snacks in bars or restaurants and if you want a light lunch you may need to purchase items such as sandwiches, quiche or croque-monsieur (toasted ham and cheese sandwich) from a bakery.

For dinner (dîner) a wide variety of cuisine is available. Much of what is available is pan-European and will be easily recognisable. There are however national and regional dishes you may wish to try. Traditionally French restaurants offered only fixed price set menus with two, three or more courses. This is slowly changing and most restaurants nowadays offer both fixed price and à la carte menus.

What to eat

Neufchâtel cheese is a heart-shaped soft cheese from Neufchâtel-en-Bray (Avenue Verte, Stage 4)

France is widely regarded as a place where the preparation and presentation of food is central to the country’s culture. Modern day French cuisine was first codified by Georges Auguste Escoffier in Le Guide Culinaire (1903). Central to Escoffier’s method was the use of light sauces made from stocks and broths to enhance the flavour of the dish in place of heavy sauces that had previously been used to mask the taste of bad meat. French cooking was further refined in the 1960s with the arrival of nouvelle cuisine which sought to simplify techniques, lessen cooking time and preserve natural flavours by changing cooking methods.

Northern France and Normandy are not particularly well-known for gastronomy, although there are a few local specialities you may wish to try (or avoid!). Andouillettes are coarse sausages made from pork intestines with a strong taste and distinctive odour. Not a dish for the faint hearted. As in nearby Belgium, moules et frites (mussels and chips) are popular light meals while Dieppe (Avenue Verte, Stage 4) is famous for hareng saur (smoked herring). Local cheese includes Neufchâtel (Avenue Verte, Stage 4) while Camembert (from lower Normandy), Brie (from the Marne valley) and Maroilles (from Picardy) are produced nearby. All are soft, creamy cows’ milk cheeses with blooming edible rinds. One way of serving cheese is le welsh, a northern French take on welsh rarebit consisting of ham and grilled cheese on toast often topped with an egg. Normandy and the Bray have orchards producing apples, pears and cherries from which fruit tarts such as tarte tatin are produced.

What to drink

In Normandy apples are used to produce cider

Both England and France are beer and wine consuming countries. In England beer sales are declining but wine is growing, while in France wine is declining and beer growing.

Although France is predominantly a wine drinking country, beer (bière) is widely consumed, particularly in the north. Draught beer (une pression) is usually available in two main styles: blonde (European style lager) or blanche (partly cloudy wheat beer). Most of this is produced by large breweries such as Kronenbourg and Stella Artois but there are an increasing number of small artisanal breweries producing beer for local consumption. No wine is produced commercially in northern France, although wine from all French vineyard regions is readily available. Cidre (cider) and calvados (apple brandy) are produced in Haute Normandy, while Bénédictine liqueur comes from Basse Normandy.

All the usual soft drinks (colas, lemonade, fruit juices, mineral waters) are widely available.

Amenities and services

For a breakdown of facilities en route, see Appendix A. This list is not exhaustive but provides an indication of the services available.

Grocery shops

All cities, towns and larger villages passed through have grocery stores, often supermarkets, and most have pharmacies. In France, almost every village has a boulangerie (bakery) that is open from early morning and bakes fresh bread several times a day.

Cycle shops

Most towns have cycle shops with repair facilities. Locations are listed in the stage descriptions, although this is not exhaustive. Many cycle shops will adjust brakes and gears, or lubricate your chain, while you wait, often not seeking reimbursement for minor repairs. Touring cyclists should not abuse this generosity and always offer to pay, even if this is refused.

Currency and banks

The currency of France is the Euro. Almost every town has a bank and most have ATM machines which enable you to make transactions in English. However very few offer over-the-counter currency exchange. In London, Paris and port towns (Dover, Folkestone, Newhaven, Calais and Dieppe) there are commercial exchange bureau but in other locations the only way to obtain currency is to use ATM machines to withdraw cash from your personal account or from a prepaid travel card. Contact your bank to activate your bank card for use in Europe or put cash on a travel card. Travellers’ cheques are rarely used.

Telephone and internet

The whole route has mobile phone coverage. Contact your network provider to ensure your phone is enabled for foreign use with the optimum price package. International dialling codes are +44 for UK and +33 for France.

Almost all hotels, guest houses and hostels, and many restaurants, make internet access available to guests, usually free of charge.

Electricity

Voltage is 220v, 50HzAC. Plugs in Britain are three-pin square while in France standard European two-pin round plugs are used. Adaptors are widely available to convert both ways.

What to take

Clothing and personal items

Even though the route is not mountainous there are some undulating sections crossing chalk downland and consequently weight should be kept to a minimum. You will need clothes for cycling (shoes, socks, shorts/trousers, shirt, fleece, waterproofs) and clothes for evenings and days off. The best maxim is two of each, ‘one to wear, one to wash’. Time of year makes a difference as you need more and warmer clothing in April/May and September/October. All of this clothing should be capable of being washed en route, and a small tube or bottle of travel wash is useful. A sun hat and sun glasses are essential, while gloves and a woolly hat are advisable except in high summer.

In addition to your usual toiletries you will need sun cream and lip salve. You should take a simple first-aid kit. If staying in hostels you will need a towel and torch (your cycle light should suffice).

Cycle equipment

A fully equipped cycle

Everything you take needs to be carried on your cycle. If overnighting in accommodation, a pair of rear panniers should be sufficient to carry all your clothing and equipment, although if camping, you may also need front panniers. Panniers should be 100 per cent watertight. If in doubt, pack everything inside a strong polythene lining bag. Rubble bags, obtainable from builders’ merchants, are ideal for this purpose. A bar-bag is a useful way of carrying items you need to access quickly such as maps, sunglasses, camera, spare tubes, puncture-kit and tools. A transparent map case attached to the top of your bar-bag is an ideal way of displaying maps and guide book.

Your cycle should be fitted with mudguards and bell, and be capable of carrying water bottles, pump and lights. Many cyclists fit an odometer to measure distances. A basic tool-kit should consist of puncture repair kit, spanners, Allen keys, adjustable spanner, screwdriver, spoke key and chain repair tool. The only essential spares are two spare tubes. On a long cycle ride, sometimes on dusty tracks, your chain will need regular lubrication and you should either carry a can of spray-lube or make regular visits to cycle shops. A strong lock is advisable.

Safety and emergencies

Weather

The whole route is in the cool temperate zone with warm summers, cool winters and year-round moderate rainfall. Daily weather patterns are highly variable.

Road safety

Where there is no cycle lane, motorists and cyclists are urged partageons la route (share the road)

While in England cycling is on the left, in France it is on the right side of the road. If you have never cycled before on the right you will quickly adapt, but roundabouts may prove challenging. You are most prone to mistakes when setting off each morning.

France is a very cycle-friendly country. Drivers will normally give you plenty of space when overtaking and often wait patiently behind until space is available to pass. Much of the route is on dedicated cycle paths, although care is necessary as these are sometimes shared with pedestrians. Use your bell, politely, when approaching pedestrians from behind. Where you are required to cycle on the road there is often a dedicated cycle lane.

Many city and town centres have pedestrian-only zones. These restrictions are often only loosely enforced and you may find locals cycling within them, indeed many zones have signs allowing cycling. One-way streets in France often have signs permitting contra-flow cycling.

Neither England nor France require compulsory wearing of cycle helmets, although their use is recommended.

Emergencies

In the unlikely event of an accident, the standardised EU emergency phone number is 112. The entire route has mobile phone coverage. Provided you have an EHIC card issued by your home country, medical costs of EU citizens are covered under reciprocal health insurance agreements, although you may have to pay for an ambulance and claim the cost back through insurance.

Theft

Secure cycle storage facility in Gournay-en-Bray (Avenue Verte, Stage 5)

In general, the route is safe and the risk of theft low. However, you should always lock your cycle and watch your belongings, especially in cities.

Insurance

Travel insurance policies usually cover you when cycle touring but they do not normally cover damage to, or theft of, your bicycle. If you have a household contents policy, this may cover cycle theft, but limits may be less than the actual cost of your cycle. Cycle Touring Club (CTC), www.ctc.org.uk, offer a policy tailored to the needs of cycle tourists.

About this guide

Text and maps

There are 20 stages, each covered by separate maps drawn to a scale of 1:100,000. The maps for the English stages 1–3 of both the classic route and Avenue Verte are based upon UK Ordnance Survey mapping and as a result differ slightly in style to those for the French stages. Detailed maps of city centres (including London and Paris) and major towns are drawn to 1:40,000. The route line (shown in red) is mostly bi-directional. Where outward and return routes differ, arrows show direction of travel. Some alternative routes exist. Where these offer a reasonable variant, usually because they are either shorter or offer a better surface, they are mentioned in the text and shown in blue on the maps.

Place names on the maps that are significant for route navigation are shown in bold in the text. Distances shown are cumulative kilometres within each stage and altitude figures are given in metres. Please note that ‘signposted’ is abbreviated to ‘sp’. For each city/town/village passed an indication is given of facilities available (accommodation, refreshments, youth hostel, camping, tourist office, cycle shop, station) when the guide was written. This list is neither exhaustive nor does it guarantee that establishments are still in business. No attempt has been made to list all such facilities as this would require another book the same size as this one. For full accommodation listings, contact local tourist offices. Such details are usually available online. Tourist offices along the route are shown in Appendix B.

While route descriptions were accurate at the time of writing, things do change. Temporary diversions may be necessary to circumnavigate improvement works and permanent diversions to incorporate new sections of cycle track. This is particularly the case in London where on-going work to create a cycle super-highway network will affect Stage 1 of the classic route for a few years. Where construction is in progress you may find signs showing recommended diversions, although these are likely to be in the local language only.

GPX tracks

GPX files are freely available to anyone who has bought this guide on Cicerone’s website at www.cicerone.co.uk/914/gpx.

Language

This guide is written for an English-speaking readership. In France, English is taught as a second language in all schools and many people, especially in the tourist industry, speak at least a few words of English. However, any attempt to speak French is usually warmly appreciated. In this guide, French names are used except for Normandie and Picardie where the English Normandy and Picardy are used. The French word château covers a wide variety of buildings from royal palaces and stately homes to local manor houses and medieval castles.

Porte St Martin in Paris commemorates battle victories of Louis XIV (classic route, Stage 11/Avenue Verte, Stage 9)