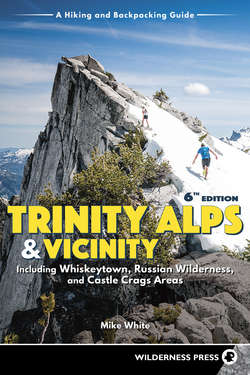

Читать книгу Trinity Alps & Vicinity: Including Whiskeytown, Russian Wilderness, and Castle Crags Areas - Mike White - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHiking and Backpacking Basics

This guide should provide you with all the information you need to hike, backpack, or ride horseback on the more than 500 miles of trails in the Trinity Alps Wilderness, Russian Wilderness, Whiskeytown National Recreation Area (NRA), and Castle Crags area. The well-researched information in the trip descriptions will assist you in planning trips and anticipating the pleasures of any particular area. This guide will help you choose the right trips, and inform you about when to go, what to expect, and what to carry with you. If you happen to be fortunate enough to eventually experience all of the trips described in this book, you won’t regret the time or effort involved.

A basic knowledge of how to read topographic maps and how to use a compass and a GPS unit are expected skills for anyone headed into the areas covered in this guide. Consequently, the book does not go into minute details about the trails. If you would like to learn more about backcountry navigation, Brian Beffort’s Joy of Backpacking (also published by Wilderness Press) is a very helpful resource.

When and Where to Go

The relatively low elevations in Whiskeytown NRA and Castle Crags State Park provide fine early- and late-season hiking opportunities. In fact, many of those trails could be hiked year-round, depending on weather conditions. Most trails in the Trinity Alps and Russian Wilderness are open by late June in all years except those with inordinately heavy snowfall, and usually remain open until sometime in October or early November. At the beginning of each trip description is a “Season” listing, which may be slightly different from this generalization; there are usually good reasons for any discrepancies. For instance, some high-elevation passes and north-facing slopes shed their snow later than lower passes and south-facing slopes. Fords of swollen streams may not be safe at the same time every year as well. Since no two years are alike, you should always exercise good judgment and acquire all the relevant information about an area when planning your visit.

IF YOU WANT TO FISH

Fishing is generally good—even fantastic at times!—in the areas covered by this guide. Almost all of the lakes in this region have been stocked with fish in the past, but stocking has been curtailed by court ruling in many of the more remote lakes in an attempt to restore the native fish populations. Reducing stocking is also a cost-cutting measure for a state government badly strapped for cash. A list of bodies of water in the state that will and will not be stocked by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife is generally available at wildlife.ca.gov. The only lakes not stocked in the past were too small and remote, or so high and shallow that they froze solid during the winter, killing the fish. Most of the trout in the backcountry lakes are eastern brook trout, as this species can reproduce without the aid of running water. However, a few lakes do have a good population of rainbow trout that spawn successfully in the running water of inlets or outlets. Some other lakes also contain large rainbow and brown trout that were stocked several years ago, such as Upper Canyon Creek Lake, which boasts a healthy population of good-size fish of all three species.

Fly-fishing in the Trinity River

Photo: Luther Linkhart

Fishing in the Klamath River system, including streams that empty directly into the Trinity River below Lewiston Dam, and all the tributaries of these streams, is influenced by steelhead and salmon runs. You may see a few adult steelhead resting in the deep pools of these streams in the summer during spawning runs. If you’re particularly fortunate, you may even see a salmon or two, but they are becoming scarce. In an effort to sustain these fisheries, salmon and steelhead runs in the anadromous waters of the Klamath and Trinity Rivers are reviewed and regulated by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife every year. Check with them for current quotas and regulations.

Of course, none of the streams that empty into Trinity Lake or the Trinity River above the lake have steelhead or salmon runs any longer. However, all of these streams of any consequence harbor some native rainbow trout, and some of the higher tributaries have eastern brook trout. The lower, more easily reached stretches of these streams are badly overfished. Stuart Fork, Swift Creek, and Coffee Creek have been hit particularly hard.

Some of the best fishing in the state occurs in the upper Sacramento River near Castle Crags. Fishing season on this stretch of the river, and nearby Castle Creek, runs from the last Saturday in April to November 15, and is restricted to artificial lures and barbless hooks.

A few streams and lakes have been stocked with golden trout and these locations are noted in the trip descriptions. Almost all the fishing information in the descriptions was based on the personal experience of this guide’s former author, Luther Linkhart, and is biased toward dry fly-fishing. Of course, a valid California fishing license and compliance with California fishing regulations are required. Good luck!

HUNTING SEASON

If you prefer not to hike in the backcountry during general deer hunting season, avoid scheduling trips during the last week of September and the first three weeks of October. Bow hunting usually precedes the opening of rifle season by about a month, but there’s little chance that a bow hunter at close range would mistake you for a deer. The beginning of bear hunting season usually corresponds to the beginning of general deer hunting season, but either extends through the last Sunday in December, or until the yearly quota is taken. Check with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife for the actual dates of each season, as they tend to vary somewhat from year to year and district to district.

Hiking in the Trinity Alps, Russian, and Castle Crags Wilderness areas during hunting season without experiencing any difficulties is quite possible. The number of hunters you encounter seems to diminish with the amount of distance you’re willing to put between yourself and the nearest road. Besides, most hunters you come across in the wilderness are typically competent and respectful backcountry users. In many ways, fall is the best season for hiking the trails in theses areas and should be enjoyed by all.

TO SKI OR NOT TO SKI?

Currently, there are no downhill ski areas operating near the Trinity Alps, Russian, or Castle Crags Wilderness areas, and there are no plans to build any in the future. The closest developed ski area is on Mount Shasta. Designated or groomed cross-country ski trails are also absent from this part of Northern California. Scott and Carter summits are about the only areas high enough for cross-country skiing or snowshoeing and reachable by car. Otherwise, you should expect to walk many wet miles in order to reach a sufficient amount of snow on which to practice these pursuits. Much of the backcountry is potentially avalanche prone as well.

The Trails

FACTORS DETERMINING TRAIL DIFFICULTY

The difficulty level of a trip is somewhat subjective and depends greatly on the weather, your physical condition, and your expectations. Of those three factors, the only one this guide can help influence is what you expect to find. For many of the same reasons, the number of days suggested for each trip is subjective as well. The fewer number of days listed is the minimum you should schedule in order to fully enjoy a trip. The greater number of days obviously includes a layover day or two when you can settle into a camp and do some nearby day hikes, or simply enjoy a rest day. Campsites and places to acquire water will be mentioned in order to help you plan your routes efficiently.

FINDING THE TRAILHEADS

All of the trailheads listed in this guide should be accessible to the average sedan. However, that sedan might be very dusty or mud-caked by the time you reach a particular trailhead. Some roads are narrow and winding, requiring a speed no faster than 15 miles per hour at times.

Because of inadequate funding, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) has had to curtail much of its road maintenance, so checking on the current conditions at a ranger station may go a long way toward preventing any prospective difficulties in accessing the trails. Keep a watchful eye whenever you drive roads near active logging operations, as the typical sedan won’t fare very well in a battle with a logging truck. Try to allow more time to get to a trailhead than you consider necessary, as many of the “highways” in the area can’t be driven at freeway speeds. The gravel and dirt roads beyond the highways will require even slower speeds.

Some of the road and trailhead signs in this area have a habit of routinely disappearing (the TANGLE BLUE LAKE sign is a classic example), which can create obvious problems. Therefore, keep track of your odometer readings and have a map resource handy in case you reach an unsigned junction.

While the safety of your vehicle when parked at a trailhead is always a legitimate concern, the chance of a break-in or other form of vandalism is quite remote in this area. Nevertheless, don’t leave valuables in your vehicle, and place any unused gear or extraneous objects out of sight in your trunk—what you may consider of little value, a vandal might deem worth stealing.

WATCHING THE GRASS GROW

Many miles of trail in the northwestern Trinity Alps are not covered in this guide for the not-so-simple reason that this area has long been a hotbed of illegal marijuana cultivation. During the 1970s and ’80s, pot growers virtually took over a vast area of territory that included East Fork New River, Pony Creek, Slide Creek, Eagle Creek, and Mary Blaine Meadow. USFS personnel did not patrol or maintain any of these trails, advising recreational enthusiasts to avoid the area altogether. In the course of events, two guard stations were burned down, shots were fired at or near USFS staff, and numerous vehicles were vandalized and burned while parked at trailheads.

In the mid-1980s, a major law enforcement effort was carried out in this area by armed forest rangers, state and federal narcotics agents, and Trinity County deputy sheriffs. Marijuana plantations were destroyed, illegal structures torn down, and large amounts of trash packed out. Maintenance crews restored some of the trails, and they were subsequently declared safe for outdoor enthusiasts to use again. That said, growing operations likely still exist in many areas covered in this book, thanks to declining government budgets for both maintenance and patrols and in spite of the fact that marijuana grown for personal/medical use is now legal and regulated in California.

Some pot farmers may arm themselves and may not appreciate your presence should you happen to stumble upon their illicit plantations. (Aside from the presence of marijuana plants, signs of illegal pot-growing activity include water lines, PVC pipes, generators, or water pumps—anything out of place in a wilderness setting, for that matter.) So check with the Weaverville Ranger Station (530-623-2121) about current conditions, and beat a hasty retreat if you stumble upon any suspicious activity.

Staying Safe

Hiking in the Trinity Alps and the other areas covered in this guide should pose no special problems that you wouldn’t encounter in any other wilderness or backcountry area in the West. However, some precautions and pretrip planning can certainly save you some discomfort. Foolhardiness or panic can easily get you into trouble here, as is the case in any outdoor area.

For instance, during the very hot and dry summer of 1981, a youth group led by two adults started up the notoriously steep and exposed trail from Portuguese Camp to the crest of Sawtooth Ridge late in the morning one hot summer day. Two-thirds of the way up to the ridge, one boy became ill with flulike symptoms and was unable to continue. The unfortunate boy was left alone in the hot sun while his companions, who were in only slightly better shape, climbed over the ridge to seek help. By the time they were finally able to secure help and climb back over the ridge, the boy was dead.

Apparently no single mistake led to this boy’s death but rather a series of poor decisions, compounded by a lack of precautions. First, the group should not have attempted to climb this trail without carrying a lot of water. Second, basic first aid training would have enabled someone in the group to recognize the symptoms of heat exhaustion and prompted them to find some shade for the stricken boy, loosen his clothes, lower his head, fan him, and above all stay with him. In retrospect, only two people should have gone for help and the rest of the group should have tried to carry the boy to shade and water.

One of the most important considerations in the backcountry is to avoid traveling alone—help could be a long time coming in remote areas. Here’s a brief summary of additional hazards.

ALTITUDE SICKNESS

A cursory examination of topographic maps reveals that altitude sickness should not be much of a problem in the areas covered in this guide. Very few of the trips exceed an elevation of 7,500 feet, with many of the trailheads in the Trinity Alps and Russian Wildernesses below 3,000 feet. Consequently, your first day on the trail should not overtly tax your body, at least from an elevation standpoint. Elevations in Whiskeytown NRA and Castle Crags State Park are even lower. Increase in altitude does aggravate distress caused by heat and dehydration, so take it easy on the trail and drink plenty of fluids, especially on the first day of a trip.

HYPOTHERMIA

Although experiencing subfreezing temperatures in this area is highly unlikely during the summer, the possibility of developing hypothermia is quite real when you’re unprepared for wet conditions and/or chilly temperatures. The combination of wet clothing and wind chill is enough to cause hypothermia at temperatures well above freezing. You can become wet and chilled not only from precipitation but also from falling into a stream or lake, or even from excessive sweating.

Hypothermia is a condition in which core body temperature drops due to loss of heat through the skin at a rate faster than the body’s ability to produce heat. A drop of 1°F in core body temperature is enough to produce shivering, which is the body’s defense mechanism to try and raise core temperature through exertion, as well as slurred speech and loss of judgment. A 2°F drop in temperature leads to loss of coordination, loss of memory, and further loss of judgment and initiative. If your core body temperature decreases by 3°F, you will be unable to walk, will experience debilitating lassitude, and without help, will eventually die.

Hypothermia is an insidious ailment, as the victim fails to realize his or her deteriorating condition, due to the loss of judgment brought on by the initial stages. When wet and cold conditions are encountered, every member of a group should watch each other closely for any developing signs of hypothermia. At the first signs of hypothermia in anyone, the group as a whole should seek shelter, build a fire where possible, and take every step to get the victim warm and dry.

If a person reaches the second or third stages of hypothermia, he or she must be helped immediately—abandoning a victim in this situation is a death sentence. With utmost haste, the victim should be placed in a shelter, stripped of all wet clothing, and placed in a dry sleeping bag with another unaffected person who has been stripped of clothing as well (skin-to-skin transfer of heat is the best remedy). If warm nonalcoholic beverages are available, they will also help the victim.

As with many backcountry maladies, prevention is the best cure for hypothermia. You should always bring waterproof and breathable clothing made from modern synthetics, such as Gore-Tex or its equivalent, whether you’re on a day hike or a multiday expedition. At the first sign of wet and/or chilly conditions, put on a shell parka and pants and wear them until conditions improve. Base layers worn next to the skin should be made of polypropylene, or natural fibers like silk or wool—fabrics that will keep you warm and transfer perspiration to the outer layers of your clothing. Mid-layers of synthetics, such as fleece or wool, serve a similar function. Cotton clothing, while very comfortable, is the worst possible fabric for wet and chilly conditions. When wet, either from the elements or perspiration, cotton loses all ability to insulate and thereby keep you warm. A well-constructed tent with a rainfly (or a waterproof tent) is an excellent investment for backpackers camping in wet weather, not to mention that it provides a haven from mosquitoes.

SUN EXPOSURE

Dehydration is a common but easily preventable condition brought on in the backcountry by strenuous exertion. Dehydration occurs when your body loses too much fluid and you don’t drink enough to sufficiently replace that lost fluid. Symptoms can include muscle cramps and lightheadedness. Not properly rehydrating can lead to severe dehydration, which will eventually become a life-threatening condition. While on the trail, make sure to drink plenty of fluids and you shouldn’t have to worry about becoming dehydrated.

Heat exhaustion and heatstroke (sunstroke) are not-uncommon afflictions in the backcountry of sunny Northern California. Heat exhaustion occurs when the rate of perspiration is insufficient to cool the body. This condition can develop when a person exercises strenuously in hot weather and does not drink enough fluids to replace those lost through perspiration. Symptoms include flushed skin, rapid breathing, and possible fainting. Drinking plenty of water or an electrolyte-replacement beverage (such as Gatorade) will prevent heat exhaustion. Moderate to severe heat exhaustion can lead to heatstroke, in which the body is unable to regulate core temperature and that temperature continues to rise—simply put, the body produces more heat than it can lose. The symptoms include pale but hot skin, rapid heart rate, mental confusion, convulsions, and unconsciousness.

Heatstroke is a serious malady requiring emergency medical intervention. Victims of both heat exhaustion and heatstroke should be removed from the sun and cooled off by sponging the skin with cool water. The treatment for someone who faints is to place their head lower than the rest of their body. Never try to give an unconscious or semiconscious person anything to drink.

Obviously, people with sensitive eyes should wear sunglasses while in the backcountry, especially when they’re on granite- or snow-covered slopes.

LIGHTNING

Occasional thunderstorms roll through this area during the summer. For further evidence, all you need to do is look around when you cross one of the high crests and see numerous old snags split, shattered, and seared by bolts of lightning.

The safest place during a lightning storm (other than being safely tucked into your bed at home) is in the middle of a wide valley in an extensive stand of trees. In addition, you should be at least 100 feet away from metal objects, including your pack. Avoid tall, isolated trees and high, open areas. Report any fires you see as soon as possible to the nearest USFS facility. Do not attempt to put out any forest fire of substantial size without help.

Threatening weather along Upper Canyon Creek (see Trip 38)

DRINKING WATER

All drinking water should be treated in the backcountry. This does not mean that all water in the backcountry is contaminated, only that because microscopic organisms are impossible to see with the naked eye, treating all drinking water is the best plan for guarding your health. Giardiasis, a severe intestinal disorder caused by the organism Giardia lamblia, is common enough in the backcountry to cause concern. High counts of coliform bacteria (including E. coli) are fairly common as well.

DANGEROUS ANIMALS

In brief: Don’t attempt to feed or pet any wild animal, and don’t carelessly leave food lying around within easy access of any mildly resourceful critters, such as bears, deer, and rodents.

Bear encounters are few and infrequent. However, carrying your food and scented items in a bear canister, or adequately hanging your food from a tree at the very least, is essential for the well-being of both you and the bears. The following guidelines should help campers and backpackers reduce the possibility of a bear encounter.

At the campground:

• Store all food and scented items out of sight in a bear locker or the locked trunk of your vehicle.

• Dispose of all trash in bearproof garbage cans or dumpsters.

• Never leave food out and unattended.

In the backcountry:

• Don’t leave your pack unattended on the trail.

• At your campsite, empty your pack and open flaps and pockets.

• Keep all food, scented items, and trash in a bear canister or effectively counterbalanced from a high tree limb (10 feet high and 5 feet out from the trunk).

• Pack out all of your trash.

Everywhere:

• If possible, don’t allow a bear to approach your food—throw rocks, make loud noises, and wave your arms. Be bold while maintaining good judgment from a safe distance.

• If a bear gets into your food, know that you are responsible for cleaning up the mess.

• Report any bear-related incidents to the appropriate government agency.

The most likely spot to encounter a rattlesnake is near or under the end of a footlog at a stream crossing. Rodents cross streams over footlogs too, and rattlesnakes often wait there for dinner to come to them. The relationship between rattlesnakes and rodents is discussed earlier (see). The only incident of a rattlesnake bite in the Trinity Alps that I’ve heard of involved a dog owner trying to get a snake off of his dog. Separating the participants in a dog–bear encounter may prove just as unfortunate. Both bears and rattlesnakes will avoid you if they can, so always allow them a route of escape. Refrain from killing a rattlesnake simply because you happen to see it: rattlesnakes are an important part of the ecosystem and were here long before people.

A human being in reasonable condition should be able to survive a rattlesnake bite without immediate treatment, provided he or she stays reasonably calm. Fortunately, rattlesnakes do not always inject venom when they strike, and if they do, bites are very rarely fatal. Of course, victims should be taken to a hospital or urgent-care facility as soon as possible, but they should ride or be carried out of the backcountry rather than attempting to walk out under their own power.

To treat a rattlesnake bite, wash the area with soap and water. If you happen to be carrying an extractor, apply suction and use the device to pull venom from the wound, but do not incise the wound. While a tight tourniquet should not be used, application of a constricting band tight enough to slow circulation but not stop pulses will help to slow the spread of venom. Keep the affected limb immobile and below the heart.

INSECTS

Although the overwhelming majority of insect bites cause no problems, the western blacklegged tick—one of California’s 49 tick species—may carry Lyme disease. If bitten by a tick, carefully grab the body of the insect with a pair of tweezers as close to its mouth as possible. Applying gentle traction, pull the tick straight out of the affected flesh without twisting, which can separate the head from the body. Once removed, place the tick in a container for later identification if necessary, and then wash the wound (as well as your hands) thoroughly with soap and water. If the bite becomes infected, you can apply an antibiotic ointment and cover with a bandage. If the wound starts to itch, swell, or redden, an antihistamine such as Benadryl may help alleviate those symptoms. Consult a physician if the wound develops a round, red rash and/or you experience flulike symptoms, which can occur anytime after three days or up to a month after you get bitten.

STREAM CROSSINGS

A number of stream crossings that would otherwise be dangerous early in the summer have been bridged. Some potentially problematic stream crossings without bridges are specifically mentioned in the trip descriptions. A few streams to be wary of during high water include Virgin Creek, North Fork Trinity River, Grizzly Creek, Rattlesnake Creek, Canyon Creek, Swift Creek, and Stuart Fork. For information on roped stream crossings, consult Brian Beffort’s Joy of Backpacking. In order to rope safely across a stream of any size, you will need a 150-foot lightweight climbing rope.

A hiker fords Stuart Fork (see Trip 5).

WILDERNESS PATROLS

Wilderness trail crews are composed of some of the hardest-working, most dedicated public servants you’ll ever meet. Unfortunately, there’s simply not enough money to fund enough personnel to do all the things that need to be done. Most of the small force of workers in this area is made up of volunteers—if they do get paid they don’t receive a ton of money. If you happen to meet a USFS, National Park Service (NPS), or state park ranger on patrol, he or she will likely be carrying a radio, first aid kit, shovel, ax, and plastic bags for picking up garbage left behind by the thoughtless few who abuse the privilege of being in the backcountry. Rangers have plenty to do in directing visitors, educating the masses, overseeing trail maintenance, and conducting rescues when necessary. Rangers can and will issue citations for flagrant violations of USFS, NPS, or state park regulations.

What You’ll Need

Maps

The maps at the beginning of each chapter of trail descriptions provide a general idea of where trips are located. Individual trips are shown in greater detail on maps sprinkled throughout the pertinent chapters. Familiarity with topographic maps and orienteering with map and compass are skills essential to successfully following any off-trail routes described in this guide, and are highly recommended for on-trail travel as well. Some conservation and hiking associations, as well as some community colleges, offer classes in these skills.

The topographic maps listed in the key information at the beginning of each trip are U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) 7.5-minute maps. These topographic maps are available directly from the federal government at store.usgs.gov and from visitor centers, ranger stations, and some outdoor retailers. A number of applications are available for creating maps to print from your home computer or for display on your smartphone.

Additional listings in the heading are for useful topographic maps printed on waterproof paper and published by the USFS for Trinity Alps, Russian, and Castle Crags Wilderness Areas. A Guide to the Trinity Alps Wilderness (2004) is a two-sided map (scale is an inch equals a mile) printed on waterproof paper that covers the entire wilderness and is quite handy for longer trips. The same is true for A Guide to the Marble Mountain Wilderness and Russian Wilderness (2004), with the Marble Mountains shown on one side and the Russian Wilderness on the other. At a scale of 2 inches equals 1 mile, A Guide to the Mount Shasta Wilderness and Castle Crags Wilderness (2001) is printed on waterproof paper and also has the two areas shown on opposite sides. California State Parks publishes a waterproof, topographic map at a scale of 3.75 inches equals 1 mile for Castle Crags State Park, which is available from the park’s visitor center.

Not mentioned in the headings but useful for trip planning and for finding directions to campgrounds, picnic areas, trailheads, and other features, the USFS also publishes smaller-scale maps covering an entire national forest for Klamath (2007), Shasta-Trinity (2007), and Six Rivers (2005) National Forests. All of these USFS maps can be purchased at ranger stations and information stations, or online at nationalforestmapstore.com.

Index of USGS 7.5-Minute Topographic Maps

TOOLS

Few tools are required for a trip into the wilderness. One important tool many hikers and backpackers like to carry is a shovel—not the big, cumbersome, or heavy type that you would use in your garden, but a short one with a sturdy blade and a strong handle. This kind of shovel serves three purposes: to scrape out a place for a fire, to put the fire out, and to dig a hole for disposing of human waste.

A fire can only be fully extinguished by drowning it out with water, stirring, and repeating the whole process over again. Simply covering a fire with dirt is usually insufficient enough to put out a campfire. Don’t attempt to put out a fire simply by dumping some dirt on it and covering it with rocks.

Human waste should be disposed of in a 6- to 8-inch hole in mineral soil a minimum of 200 feet from a campsite or water source. If you must dig a hole in sod, remove and replace an intact piece, using a shovel, as opposed to a stick. Please don’t bury garbage—buried garbage will be dug up by some critter. Only cook as much food as you can eat.

Modern backpacking tents have done away with the need for ditching, or digging shallow ditches around the perimeter of your tent. Digging out a level place to pitch a tent is also unnecessary. Such scars remain for a long time.

The second important tool is a good pocketknife or multitool, which is invaluable for a number of purposes: making repairs or cleaning fish, for instance. A pocketknife or multitool with a pair of pliers can be particularly useful.

Permits and Practices in the Wilderness

WILDERNESS PERMITS

Although regulations are prone to change, a wilderness permit is likely to be a continued requirement for any overnight stay in the Trinity Alps Wilderness. Free wilderness permits are available by self-registration at any ranger station around the Trinity Alps. Currently, wilderness permits are not required for the Russian Wilderness or Castle Crags Wilderness. However, if you are planning to backpack and have a campfire in the national forests covered in this guide, you will have to procure a campfire permit, which is free and available from any USFS ranger station or information center. Whether or not wilderness permits are required for overnight visits, you should still inform a responsible party about your plans and itinerary, providing them with information about what agency to contact if you fail to return on time.

Visitor and information centers and ranger stations administered by USFS, NPS, and state park personnel can usually provide good information on the current status of trails and conditions in the backcountry. For more information, contact the following facilities:

• Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area

Whiskeytown Unit

PO Box 188

Whiskeytown, CA 96095

530-242-3400 (headquarters), 530-246-1225 (visitor center)

nps.gov/whis

• Trinity Alps Wilderness

Shasta-Trinity National Forest

3544 Avtech Parkway

Redding, CA 96002

530-226-2500

fs.usda.gov/stnf

WEAVERVILLE RANGER DISTRICT

210 Main St. (CA 299)

Weaverville, CA 96093

530-623-2121

Klamath National Forest

1312 Fairlane Road

Yreka, CA 96097

530-812-6131

fs.usda.gov/klamath

SALMON RIVER RANGER DISTRICT

11263 N. CA 3

Fort Jones, CA 96032

530-468-5351

• Russian Wilderness

Klamath National Forest

1312 Fairlane Road

Yreka, CA 96097

530-812-6131

fs.usda.gov/klamath

SCOTT RIVER RANGER DISTRICT

11263 N. CA 3

Fort Jones, CA 96032

530-468-5351

• Castle Crags Area

California State Parks

1416 Ninth St.

Sacramento, CA 95814

800-777-0369 or 916-653-6995

www.parks.ca.gov

CASTLE CRAGS STATE PARK

PO Box 80

Castella, CA 96017

530-235-2684

Shasta-Trinity National Forest

3544 Avtech Parkway

Redding, CA 96002

530-226-2500

fs.usda.gov/stnf

MOUNT SHASTA RANGER DISTRICT

204 W. Alma St.

Mount Shasta, CA 96067

530-926-4511

CAMPING RULES AND ETIQUETTE

Campsites should be at least 200 feet from streams and lakes where possible. Only dead wood lying on the ground may be used for firewood. Don’t cut green foliage or upright trees for any purpose. The use of motorized equipment within wilderness areas is strictly forbidden, except where specifically authorized on existing mining claims. Equestrians should check with the USFS about forage and tie regulations for saddle and pack animals. A maximum group size of 10 persons is in effect for all wilderness areas covered in this guide.

CAMPFIRES AND FIRE RINGS

Most recreational enthusiasts appreciate a fire at their campsite as a marvelous, cheery accessory to their wilderness experience. However, wise use of the firewood supply today will allow future wilderness visitors to enjoy the same experience. Nowadays, some of the most heavily used areas lack an adequate supply of firewood, and as a result campfire bans have been instituted at a handful of the more popular locations. In other areas, please consider whether or not a campfire is appropriate, and if so, keep it small.

Fire rings can be eyesores, particularly the high, built-up variety, which tend to collect trash that is hard to remove from between the rocks. They also make fully extinguishing a fire much more difficult, as coals continue to smolder in the chinks between the rocks. Start a campfire only in existing fire rings—never construct a new fire ring, and don’t cook over an open fire—backpacking stoves are much more efficient.

This campsite is too close to the water.

TRAIL COURTESY

Cutting switchbacks causes erosion and could possibly dislodge a rock onto an unsuspecting hiker below—so don’t do it. When meeting others on the trail, downhill hikers should yield the right-of-way to uphill hikers. Saddle and pack animals have the right-of-way; when encountering stock, quietly step well off the trail on the downhill side, as they may become nervous when crowded or frightened by unexpected noises or movements, which ultimately could result in potential injury to both hikers and riders.

Any form of trash is an affront to a wilderness experience. Don’t litter! Be a good Samaritan and pick up any trash you may encounter at camp or on the trail.

How to Use This Book

Trips are numbered and labeled to show start and finish locales. At the beginning of each trip description, the following bits of information are provided.

Trip Type

This entry describes whether the trip is a day hike or an overnight backpacking trek. For overnight hikes, a range of days necessary to enjoy the features of the entire trip is also listed.

Distance & Configuration

Lists the total distance in miles from the trailhead to the end of your journey, along with the type of hike (out-and-back, loop, or point-to-point).

Elevation Change

This figure reveals how much elevation gain and loss hikers will experience from the trailhead to the ultimate destination for out-and-back trips (which should be doubled for the entire distance), and the total elevation gain and loss for point-to-point and loop trips.

Difficulty

The overall difficulty of a trip is measured as easy, moderate, or strenuous. This rating is somewhat subjective, as your level of fitness, experience, and knowledge of the backcountry will influence your particular rating of a trip’s difficulty. The ratings listed here should be fairly accurate for the average hiker or backpacker.

Season

This entry suggests the best times of the year to fully enjoy the attributes of a particular trip, including the average times of snow-free trails. The season may vary some from year to year based upon the previous winter’s snowpack and how quickly the snowpack melts in the spring and early summer.

Maps

The USGS 7.5-minute topographic maps for each trip are listed here, along with any recommended USFS or state park maps.

Nearest Campground

This listing is for visitors who may wish to camp in a developed campground before or after a trip. In addition to the main trip description, many additional side trips, cross-country routes, or alternative routes are described and are easily identifiable so as not to be confused with the main trip description.

The Trips

Each trip description begins with some general information about the condition of the trail and the features of the area you should expect to experience. Within the trip highlights are any special considerations or necessary cautions that are important to effectively plan your trip. Also, the general information includes an idea of the amount of traffic you should expect to encounter along the trail and at destinations. Each trip also includes a map and an elevation profile. For out-and-back trips, the profile shows data for the trip from the trailhead and to your destination but not your return journey retracing your steps.

Starting Point

This section provides you with detailed driving directions and distances to each trailhead, as well as information about the road surfaces and conditions. Trailhead facilities are also noted where they exist. Nearby campgrounds are listed in the trip summary information and are sometimes described in this section based upon level of use, scenery, privacy, protection from the elements, unique natural features, proximity to fishing, swimming potential, and the availability of possible side trips.

Caring for the Backcountry

Whiskeytown, Shasta, and Trinity are three separate islands of national recreation area surrounding giant reservoirs of the same names, which were set aside in 1965 and are currently managed by the NPS. Centered around Whiskeytown Lake, the Whiskeytown Unit consists of around 42,000 acres of land. The area has 24 different trails, many of which are favorites of day hikers and mountain bikers.

The wilderness areas described in this guide are relatively new to the wilderness system; they were set aside two decades after the original wilderness bill was passed in 1964. The Trinity Alps, Russian, and Castle Crags wilderness areas were all created as part of the California Wilderness Act in September 1984.

The Trinity Alps Wilderness consists of about 518,000 acres, with boundaries close to what several conservation organizations and Trinity County lobbied for over the years prior to wilderness designation. Such a designation was a triumph for wilderness proponents and nonmechanized recreational enthusiasts. The act also required that previously existing private lands within the designated wilderness boundary would be exchanged or eventually purchased. Until such buyouts are completed, any private inholdings will be nominally managed as wilderness. With more than 500 miles of trail, the Trinity Alps are a backpacker’s paradise.

The Russian Wilderness is much smaller than the Trinity Alps, with only 12,000 acres of land set astride the apex of a divide separating the Scott and Salmon Rivers. The area has a buffer of national forest land on all but the east side, land which is mostly held in private hands. With more than 30 miles of trail within the wilderness and surrounding national forest, this area is well suited for day hikers, as well as for weekend backpackers.

Castle Crags Wilderness is even smaller than the Russian Wilderness, with only about 10,500 acres of protected wilderness. This small pocket of backcountry is bordered by Castle Crags State Park to the southeast and national forest land to the northwest, but the remaining land around the wilderness is a checkerboard of private and public holdings. There are nearly 30 miles of maintained trail within the wilderness. Castle Crags State Park adds another 4,000 acres to the Castle Crags complex, and another 30 miles of hiking trails. Due to the compact size, the Castle Crags area is best suited to day hikers.

Owners of mining claims within the designated wilderness areas may continue to explore and mine their claims, and must be allowed reasonable access to do so. Fortunately, no new claims may be filed without an act of Congress. The USFS validated all existing claims in the development of the Wilderness Operation Plan, which established strict environmental regulation of all mining activities.

What these marvelous areas will look like in the future depends on how we treat them today. Since major population centers are hundreds of miles away, these areas have not been prone to the heavy recreational use that is prevalent in the Sierra Nevada. Far more people were here 150 years or so ago than now, when preservation of the wilderness was not on the minds of the early miners and settlers who ravaged the land for their own economic gain. The area has recovered quite nicely from the debacle of the mining days, thanks to a scarcity of human beings in the nearly century and a half that followed. Recreational use of the wilderness has declined in modern times—a boon to solitude seekers but perhaps not so great for the protection of wilderness itself. Without enough advocates of the wilderness who appreciate the numerous blessings the natural world has to offer, who knows what fate could ultimately befall this wonderful area.

Hikers can follow several guidelines for the preservation and health of the backcountry. A simple list of widely accepted wilderness practices follows:

• Don’t leave food or scented items in your vehicle. Bears have been known to break into cars in search of food.

• Pack out your trash, including aluminum foil, which does not burn completely.

• Start campfires only in existing fire rings. Keep fires small, and use only downed wood. Make sure that fires burn completely out before leaving the area.

Never feed or approach deer.

Photo: Luther Linkhart

• Wash dishes and bathe far away from lakes and streams—at least 200 feet from any water source. Use only biodegradable soap.

• Use only existing campsites whenever possible. If you must develop a new site, establish camps at inconspicuous sites away from the trail and remove all traces of your presence upon leaving. Camp only on mineral soil, not vegetation. Don’t build improvements such as fireplaces, rock walls, ditches, etc. Camp at least 200 feet from water.

• Filter, boil, or purify all drinking water.

• Don’t cut switchbacks, and avoid walking on meadows and wet areas when possible. Stay on the trail.

• Preserve the serenity of the backcountry. Avoid making loud noises.

• Keep group size to a minimum: 10 people is the limit in the Trinity Alps and Castle Crags, 25 in the Russian Wilderness.

• Yield the right-of-way to equestrians. Step well off the trail on the downhill side. Yield the right-of-way to uphill hikers.

• Leave the wilderness as you found it, or better than you found it, if possible.