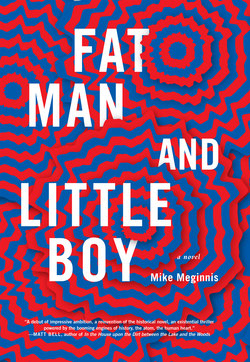

Читать книгу Fat Man and Little Boy - Mike Meginnis - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA BAG OF RICE

They find a home. It is a flimsy-seeming thing. Damp rags flutter yellowed on a line of cord stretched nearly taut between a pole and a tree branch. If there were a sun they would dry by its light. Little Boy looks up to his little brother. Fat Man wears a tired, bearlike expression, fists clenched, head seeping down into neck and chest like a mudslide.

“There must be food inside that home,” Fat Man says, “but there are also living people.”

“If I give you some money,” says Little Boy, “can you go inside and get the food?”

“I thought you would get the food. You’re supposed to be my big brother. You have to take care of me.”

“I’m just a little boy. I’m scared to go inside.”

“But I’m even younger than you,” Fat Man pleads. “What if they know I left you out here? What if they come out here to get you because they know you’re really in charge? What if they’re angry because you sent your little brother?”

Little Boy strokes the fat man’s gut. “You need to be brave and do as I say.”

“I’ll go in if you come with me. You don’t want to be out here alone if the soldier comes, or the man who had our cash case before we did. He might not be dead. We never saw his body.”

“I’ll hide,” says Little Boy.

“Come on,” says Fat Man. “You’re coming.”

With a grip that hurts, he grabs Little Boy by the shoulder. They march to the home and knock on the door. It rattles. A woman cracks open the door, draped in purple robe and white sash. Her eyes take them in without comment. She has seen stranger things than white men in mismatched clothes. She does not move to welcome them.

Little Boy elbows his brother, whispering, “Go on. Food.”

“I don’t know Japanese,” says Fat Man, as if this has just occurred to him.

“Mime it.”

Fat Man looks down at Little Boy and back at the woman. Jagged white patches of her scalp shine through thinning hair. Fat Man brings his hand to his mouth as if cupping a handful of rice and eats from his palm. He nods to the Japanese woman, repeats the action. She does it back—and also, by way of an offer, pretends to drink a cup of water. Fat Man smiles and nods.

Little Boy fans out a small handful of bills. She snatches one from his hand; one of the white crescents of her long, dead nails nicks his skin. She peers into the face of Lincoln, perhaps imagining a name for the face (not Roosevelt, not Truman) before settling on the numbers in each corner. The rate of exchange is a mystery. What does the woman think the bill is worth? She secrets away the bill inside her robe and leads the brothers inside.

There is a shirtless man lying motionless on a bed mat; he glistens with sweat and his skin is blotched purple. At eye-level, he has a small potted tree with sweet green leaves like flower petals. One arm extends to touch the pot. The other’s wrapped around his face, which is obscured from mustache to hairline. His lips part and whistle softly with each breath. A second man, a soldier, is propped up against the wall, his machine gun wrapped in both arms and framed by crossed ankles, like a strut supporting his body. A helmet falls over his eyes. He has a patchy beard, and his shoulders and chest are dusted with fallen hairs. His hands are bloody at their knuckles. He is also purple-blotched.

Fat Man squeezes too hard. Little Boy shrugs off his brother.

“That’s him,” whispers Fat Man.

The woman sets up a small stove, fills a pot with water.

“Your soldier?” says Little Boy.

“I think so.” Fat Man folds his hands together and begins twiddling furiously. His stomach rumbles. The woman gives both of them a cup of water. Little Boy hands her another bill. They chug the water, wipe their mouths with the backs of their hands. The woman brings them more. This time Little Boy does not give her more money. If she wishes to protest she does not have the words.

“We should go,” says Little Boy.

“But I’m hungry.”

“We can get food somewhere else.”

Fat Man whispers, harshly, “You already gave her the money.”

“We have more.”

The sitting soldier starts. The woman looks at him. She looks at the brothers, clamping her hand shut in front of her mouth.

“It means shut up,” says Little Boy out the side of his mouth.

“I know what it means,” says Fat Man.

They wait. The water comes to a boil. The woman pours in rice. Little Boy cranks his arm in circles, motioning for more. She glares, relents, adds more—and more water. Now she must bring it back to a boil. The brothers stand hapless at the door, swaying on their tired knees. There is a red radio in the corner with several batteries scattered beside it. They might be spent or waiting for their chance.

“Do you think they’re loaded?” whispers Fat Man. “The guns?”

“Shut up,” whispers Little Boy.

“I never actually saw them fire. All this time I’ve just been assuming.”

“It’s the safe assumption,” says Little Boy. He pinches his brother’s thigh. Fat Man grits his teeth, thumps Little Boy on the back of his head. The woman in the purple robe stares at them. A lock of gray-streaked hair falls from her scalp.

She empties the rice into a brown cloth sack. Fat Man takes the sack from her. She motions for them to leave. When they hesitate, she hoists an invisible rifle and fires off several rounds, heaving from the recoil of each shell. She mimes pushing a helmet up from over her eyes to better see her kills.

“I wanted meat,” moans Fat Man. “All my life so far it’s always been rice. I need something else. Something filling.”

Little Boy rolls his eyes. He holds out the rice in one hand, demonstrative, and then his other hand, empty. He motions with it for something else, something more. He takes a ten-dollar bill from his pocket. The woman shakes her head, crosses her arms, waits for them to leave.

“Please,” says Fat Man. He rubs his tummy. Speaks slowly, as if she’ll better understand. “I am so, hungry.”

“Shut up,” says Little Boy. He pockets the bill, hands his brother the rice, and tugs him by the elbow. The sitting soldier snorts. His head lolls forward and his helmet drops off. It hits his kneecap and thuds on the ground. His eyes shoot open. He squeezes the gun with his whole body. He sees the white boy, the white man—his prisoner—and nearly falls on his face trying to lift the gun. He calls out. The man with the potted tree shudders awake. In his panic he knocks over the little tree.

There is a moment where the man with the potted tree looks merely startled. He wears the blankness of confusion. Then a malice enters his body. He looks on the brothers with hatred—knowing hatred, as if they are old enemies.

“Run!” screams Little Boy.

Fat Man knocks the sliding door crooked as he forces his way through.

The soldier and the shirtless man follow, both hollering weakly. Just outside the doorway, the soldier raises his gun and shoots. The bullets whistle past. Dirt bursts around their feet and then farther out.

Their pursuers stumble and bark at them. “Assholes,” screams the soldier, demonstrating his obscene English. “Bastards.” Another shot. The shirtless man falls to his knees and throws up.

The brother bombs plunge into the woods, Fat Man heaving like a panicked ape, Little Boy whipped by thin branches, loose roots, string trees. They run blind, surrounded by sinister rustling, leaves crunching underfoot. Soon rain begins to fall, making the whole forest seem to swarm with lives, with sick Japanese, with raging soldiers. Sometimes they hear a distant curse. They fall and scrape their knees. They stop to breathe when Fat Man says that he can’t make it, he won’t make it. A twig snaps. They’re running again.

They come to an abandoned farm, now lousy with rotten gourds and collapsed melons. This could have happened many ways, but Little Boy chooses to believe the family collapsed when the men were called to fight the Yanks.

“I can’t run anymore,” heaves Fat Man. “I’m going to throw up. I’m so thirsty.”

“One thing at a time,” says Little Boy. “First we hide and hope they don’t kill us.” He surveys the land. There is a shelter, but someone may still live there, and the spot is too obvious. Little Boy spies a slightly raised patch of dirt, a very small hill, crowned with dead vegetables and wild grass. He leads his brother there. Fat Man hobbles, clutching at his lungs through his chest as if to arrest their labors.

“Lie down in the muck,” says Little Boy.

Rain is pelting them loudly. Fat Man does as he is told—belly up like a dead tuna.

Little Boy kicks mud on his brother, and gourds and so on. “Lie very still,” he says. He lies down as well, on his belly, head-to-toes with Fat Man, the rice bag clutched under his chest. He wallows. He watches the woods where they came from.

“Your suit,” says Fat Man, horrified.

“It’ll wash out, or I’ll buy a new one.”

Little Boy listens for gunfire. He waits for the soldier. His brother’s breathing calms, and slows. Soon they are breathing together. Their bodies swelling and diminishing, touching and shying away. The brother bombs take great care in their breathing.

The soldier and the husband all purple-blotched are searching the field, shooting anything that moves. The soldier has the gun. The husband serves as a spotter, his shouts followed by three rounds. The mud accepts the bullets. They are far off but not so far.

Little Boy tries to count the shots. He doesn’t know how many bullets the soldier has. It can’t be too many.

“Here!” calls the husband, very close to them. Not in English, but they know. Three rounds into the dirt. Nothing. The soldier swears. The husband coughs. He sways into Fat Man’s view, standing over the brothers, his dirty heels at eye level. The husband coughs.

A dry rustle—some bird or rodent. The husband points in its direction, coughing into the back of his hand. Three rounds into the dirt.

The husband has an awful coughing fit. Something wet comes out of him. The soldier stops shooting for a moment. He joins the husband and holds him like a brother. The husband vomits on the soldier. There was not much in him. Now, less. He collapses, his body landing with a great whumph only feet from the brothers. His hand, a pale claw between them, twitches once, and then is done but for the slightest pulse of blood beneath the skin. He is dying of what killed the short soldier, which is something in the air, a mystery. Rain shivers on his skin. Death calms the hand.

The soldier’s legs are weak. He coughs as the husband coughed. He hacks.

He says, “This isn’t how he dies.” He shoots the husband through throat and face. Blood foams. “This is how he dies.”

He says, “We will not wait for the Americans to do what we can do ourselves.”

He says, “This is how I die.”

He pushes the butt of his rifle into the mud. He kneels before it and slides the barrel past his teeth. Balancing on his left knee, he raises his bare right foot, presses his right knee to the rifle. He puts his toe on the trigger. One round. Flesh and chips of bone. The body falls.

Little Boy darts up on his feet. He runs away to throw up what’s inside him. Fat Man wipes the rot and mud from his face and shoulders, chest and gut. Little Boy still has the food, but he will come back, and then they can eat. Rain drums on Fat Man as if he were a tarpaulin. Two bodies grow cold nearby. He feels at home here. He looks up at the clouds. He is like the bodies, he thinks, but he is also the home of a terrible hunger. That is the chief difference.

They hardly notice anymore the rot of the bodies. Busy little white worms tunneling the flesh, other bugs as well—spiders on their faces, flies on their extremities. This time the soft meat of their cheeks will be the first to go, and then their eyes. The skin between their thumbs and forefingers. The pink beneath their nails. The soles of their feet.

The brother bombs leave them like this. Eat rice from their bag with dirty hands. Open their mouths and tilt their heads back to drink rain.

Little Boy says, “What did you do to that soldier?”

Fat Man, incredulous: “What did I do? What did we do.”

Little Boy, blank: “What did we do?”

Fat Man doesn’t say. Doesn’t know how. They walk together.

They will walk for days. They will huddle for warmth. They will say few words. They will be brothers.