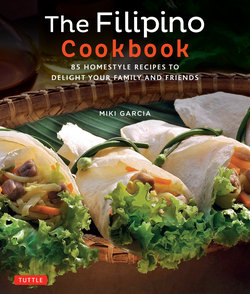

Читать книгу Filipino Cookbook - Miki Garcia - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFilipino Cooking:

Asia’s Best-kept Culinary Secret

My adventure with Filipino cooking began when I lived in Manila and in rural Iba (in Zambales Province) for about a year in the 1990s. I had always loved the country and the people of these tropical islands; however, it was only after living there for several years that I discovered and grew to love the amazing variety of foods that the Philippines has to offer. When I met and later married my Filipino husband, my love of the cuisine was further strengthened since he was from the province

of Pampanga in Central Luzon, which is considered by most Filipinos to have some of the best cooking in the nation.

Kapampangans—as the people from Pampanga are called in Filipino—are skilled cooks and spend a great deal of their time preparing fine dishes and sharing sumptuous meals with relatives and friends. When not cooking, the Kapampangans are generally thinking about what to prepare for their next meal. This great passion for food and attention to detail means that my husband loves to spend time in the kitchen, and even when I am cooking he likes to interrupt me and often offers to take over, especially if he feels I’m not doing things correctly the “Kapampangan way.” Due to this, I can truly say that his Kapampangan food culture has thoroughly rubbed off on me over the years.

Even though we have lived in many other countries of Asia and Europe and now live in America, I prefer to cook Filipino dishes whenever we entertain because I find that everybody loves the food. Over the years I have scribbled enough recipes to fill up several notebooks. For many years, I tried to find a cookbook of Kapampangan and other regional Filipino recipes that would satisfy the discriminating tastes of our Filipino friends and relatives, but I could never find one. I ended up asking my foodie friends and relatives for their favorite recipes, trying them out whenever I could, and, through trial and error, compiling a large collection of recipes that seem to exemplify the best dishes and flavors from all parts of the archipelago. Thus, this cookbook, the result of that effort, reflects the very best of Filipino cooking, and the recipes encompass a large selection of traditional and authentic dishes that can be enjoyed by anyone on any occasion and are accessible to Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike.

Filipino cuisine is one of the best-kept culinary secrets in Asia. Unlike Japanese, Chinese or Thai food, its dishes are not readily available in restaurants. Filipinos love to entertain in large groups and have a tradition of throwing large and loud parties at home. And so it is only in Filipino homes—wherever they are around the world—that can one find truly authentic Filipino cuisine.

Like other cuisines, Filipino cooking reveals a great deal about the history and geography of the place from which it sprang and the people who created it. The dishes were not developed in the kitchens of royal palaces or by wealthy aristocrats, and nor is there a long tradition of dining out in restaurants. The food is instead the creation of the common folk. In short, Filipino cuisine is the everyday “people’s food.” Its dishes are prepared to be enjoyed by everyone whenever there is a reason or occasion to gather and celebrate. Filipinos view food primarily as a means of connecting with family and friends rather than an end in itself.

One of the things I love about Filipino cuisine is its simplicity. By and large, the dishes do not require any special utensils, there are no complicated techniques, and it does not use many exotic or expensive ingredients. Most of all, preparation times are short since it’s often too hot and humid in the Philippines to spend very much time in the kitchen!

The ingredients required to make Filipino dishes are, for the most part, very easy to find. Expatriate Filipino communities, and markets catering to their needs, have sprung up in many urban areas around the world. In addition, a large number of Filipino ingredients originally came from the New World (brought over by the Spanish from Mexico) and can now be found in most large and well-stocked supermarkets (see pages 12–17 for a list of Essential Filipino Ingredients).

The Filipino national cuisine is an amalgamation of many different regional styles from the various islands as well as many historical influences from abroad. The Filipinos themselves describe their cuisine as sari-sari (varied) and halohalo (mixed) because of the wide array of influences found even within a single meal. Filipino cooking can truly be considered a melting pot, deeply influenced by over 100 different island ethnic groups as well as by settlers from all parts of Asia, and by the Spanish and American colonizers.

The native inhabitants of the islands are known as Aetas, who still live in the mountains of Luzon and Mindanao. They are believed to share the same ancestry as the aboriginals of Australia and the Papuans of New Guinea. The arrival of the Malayo-Polynesian peoples from the Asian mainland via Taiwan 6,000 years ago drove them into the mountains, and Malayo-Polynesians are now the predominant inhabitants of the Philippines. Their cooking styles involve the preparation of foods by boiling, roasting and steaming using coconut milk and peanut oil. The roasting of a whole pig, known as Lechon, is believed to be an ancient Polynesian practice.

Regular contacts with the Chinese also influenced Filipino cuisine. Chinese traders, who visited and settled on the islands from the fifth century onward, brought their culinary techniques and ingredients. Fried Rice Noodles (page 93) and Spring Rolls (page 31) are two typical Filipino dishes with their roots in China. Many of the typical Filipino sawsawan, or dipping sauces, are also of Chinese origin. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, the islands were also visited by Arab, Japanese, Thai, Vietnamese, Javanese, Cambodian, Indian and Portuguese traders. Each of these cultures subtly influenced the evolution of the local cuisine.

The Spanish colonization of the Philippines in the sixteenth century lasted for 300 years and brought significant Spanish and Mexican influence, via Spain’s colonization of that country, to the food culture of the islands. Located on the vital sea routes of Asia, the Philippines became a lucrative trading port for the Spanish. In exchange for sugar and other local products, the Spanish brought chili peppers, tomatoes, corn, cacao and potatoes from the New World. It is said that as many as 80 percent of local Filipino dishes have some Spanish or Mexican influence, either because of their ingredients or because they are local adaptations of original Spanish or Mexican dishes.

Many Chinese dishes that were introduced during the Spanish colonial times were given Spanish names. For example, the ever-popular Chinese rice congee was given the name Arroz Caldo (Rice Porridge with Chicken, page 92), while Chinese-style fried rice was called Morisqueta Tostada—commonly known by its Tagalog name, Sinangag (Fried Rice with Egg, page 91). Spanish food and culture, and the Catholic religion, continue to define the modern-day Philippines even though Spanish colonial rule ended in 1898.

Following the Spanish-American War, these islands fell under the spell of American culture during a time of rapid modernization. American-made canned foods became widely available and people used them to create new dishes. Canned meats and sausages became popular staples as did canned fruit cocktails and condensed milk. Karne Norte, for example, is a popular dish consisting of canned corned beef sautéed with garlic and onions, and Halo-Halo is a delicious dessert of shaved ice with sweet syrups and canned evaporated milk. The Philippine-American experience gave the Filipinos many new ways of turning foreign food influences into something delicious and uniquely Filipino.

Regional Cooking Styles

In addition to these foreign influences, the geography of the Philippines has also contributed to the diversity of its cuisine. As an archipelago comprising of 7,107 islands and seventeen regions, 120 different ethnic groups and 170 different languages, the formation of regional cooking styles is inevitable. Regional traditions, preferences, and available ingredients can transform a dish into something entirely different as one travels from one end of the archipelago to the other. To give you a sense of the richness of Filipino diversity in its cuisine, this book includes the best recipes from these various regions—from the rugged north shores of the Ilocos region to the southern island of Mindanao.

On the northwest coast of Luzon, between the mountains and the sea, is the Ilocos region. Here, the land is rugged and dry. In this harsh climate, the Ilocano people survive by being frugal and hardworking. Ilocano meals include an abundance of vegetables with some type of meat as the main feature of the meal. Ilocanos prepare their vegetables by steaming or boiling them with a dash of sautéed fermented shrimp paste. Red meat dishes are not commonly found, but freshwater fish are featured prominently. Their signature vegetable dish, Pinakbet (Mixed Vegetables with Anchovy Sauce, page 80), includes plenty of locally grown vegetables like bitter gourd, okra, and eggplant served with a tasty anchovy sauce.

Pampanga has a well-earned reputation as the home to the most creative and refined cuisines found in the Philippines. Located in the central part of Luzon just east of Manila, Pampanga’s fertile soils and fish-filled rivers give the region the necessary ingredients to build its well-deserved reputation. Spanish chefs provided the Kapampangans with just enough guidance on European cooking techniques to enable them to create their own unique and delectable native dishes. Soon these dishes would outshine their European equivalents on the tables of Spanish royalty (it was the Kapampangans who prepared the meal at the proclamation of the first Philippine Republic). Among the original Kapampangan recipes featured in this book are Kaldereta Beef Stew (page 53), Oxtail Vegetable Stew (page 56), Traditional Tocino Bacon (page 50), Chicken Tamales (page 28), Kapampangan Paella (page 89), and Filipino Leche Flan (page 108).

The Bicol region is located at the southern tail of the Luzon peninsula, and includes some of the surrounding small islands. A part of the “Ring of Fire,” it has several volcanoes whose lava flows provide the region with its fertile and lush green landscape. Possessing an ideal climate for coconut trees, the region is one of the major coconut-producing provinces in the Philippines, and so their dishes often include coconut ingredients. Coconut milk, for instance, is cooked with virtually everything—vegetables, meat, and seafood. Their signature dish, Bicol Express (Fiery Pork Stew with Coconut, page 49) is pork simmered in coconut milk with a generous helping of spicy peppers (Bicolanos are famous for using hot peppers to liven up their regional dishes).

The Visayas region of the Philippines consists of a group of islands that draws upon the abundance of the sea to create its cuisines. I’ve included Visayan dishes like Filipino Ceviche (Kinilaw na Tanigue, page 77), which is fish marinated in vinegar and then eaten raw—a typically Visayan way to enjoy fresh seafood from the local waters. This is a region with a large population of Chinese settlers, so there is a range of Chinese-influenced specialties, such as Wonton Soup (page 37) and Noodle Soup with All the Trimmings (Batchoy, page 40), reflecting that influence.

At the southeastern end of the archipelago is the second largest Filipino island, Mindanao. It was here that Muslims from Indonesia and Malaysia converted the people to the religion of Islam. When the Spaniards arrived, they were unable to completely dominate the island due to the resistance of its recently established Muslim religion. This separatist attitude has flavored the development of Mindanao’s culture and cuisine. Mindanao offers a wide range of exotic dishes, and, though Christians form the majority of the population of Mindanao today, the Islamic religion continues to be a dominant influence on this island’s cuisines (pork dishes, for example, are hardly present). Their distinct chicken curry is simmered with taro roots in a very spicy sauce and served with rice. Mindanao food, especially the Sulu and Tawi-Tawi Islands, is renowned for its use of spices such as turmeric, cumin, lemongrass, coriander, and chilis. In this warm climate, spices help keep food from spoiling while lending richness to the dishes.

As one travels through the Philippines, each of the dishes encountered reflects the character and spirit of the people who live there. The Filipino people have a loyalty and devotion to their home regions matched only by a feeling of national pride borne from centuries of foreign rule.

Foods for Celebrations

Filipinos love to celebrate! Throughout the year they will find any excuse to hold a feast in order to prepare delicious foods and socialize with friends and family. Of all the annual events that are an occasion to celebrate, the most conspicuous event of the year is the town festival called fiesta in honor of the town’s Catholic patron saint. As a result of almost four hundred years of work by Catholic missionaries, the Philippines is the largest Catholic country in Asia and Filipinos have embraced their Catholic beliefs and customs, especially the annual fiesta.

The day’s festivities start at the crack of dawn, when a band plays music while walking the streets of the town, awakening the whole village. Richly embroidered tablecloths are spread and tables are set in preparation for the day’s feast. The culinary centerpiece of the celebration is the beloved Lechon, a whole pig stuffed with rice and roasted slowly over a charcoal pit. The sight of this distinctly Filipino fiesta food will immediately conjure mouthwatering childhood memories for all adult Filipinos.

Another time for food and celebration is All Souls’ Day when Filipinos visit cemeteries to pay respects to their deceased loved ones. All through the night of November 1st, Filipinos eat, sing, and gossip—while large amounts of food and drink are passed around and over tombstones. This same celebratory ethos applies to funerals, where refreshments are provided for everyone in attendance and there is a sense of communal gaiety. Typical meals eaten on these days are Pig Blood Stew (Dinuguan), Steamed Rice Cakes and Sautéed Bean Thread Noodles (page 95).

The biggest national Philippine celebration is Pasko, or Christmas. Filipinos do not confine the celebration to December but will start as early as September when they begin hanging Christmas lights and singing Christmas carols. They even continue the celebration past Christmas and make the first Sunday of January the official end to their holiday reveling. From the 16th of December through Christmas Eve, Filipinos celebrate Simbang Gabi, a Filipino version of Misa de Gallo (Mass of the Rooster), a nine-day celebration held at four in the morning on each day. An integral part of Simbang Gabi is the availability of refreshments from local street vendors. Sleepy and hungry churchgoers can enjoy Coconut Sponge Cakes (Bibingka, page 103), Purple Rice Cakes with Coconut Shavings (Puto Bumbong), Chicken Tamales (page 28), Filipino Hot Chocolate (page 105) and Healthy Ginger Tea (Salabat, page 107) as a part of the celebration. As Christmas Eve becomes Christmas morning, family members gather to share a festive Noche Buena meal of Glazed Christmas Ham with Pineapple (Hamon, page 49), cheese, lechon, Spring Rolls (Lumpiang Shanghai, page 31), Fried Rice Noodles (Pancit Guisado, page 93), Barbequed Chicken Skewers (page 61), Fruit Salad, Chicken Macaroni Salad, and other dishes.

Finally, New Year’s Eve provides another chance for family to gather around a table of celebratory foods. This meal is called the Media Noche and is served just before midnight strikes. Filipinos believe that plenty of food on the table means a year of plenty for everyone in the family. Twelve different fruits, especially round ones like grapes and chicos (or sapodilla, a brown berry with a sweet and malty taste) that resemble money, are displayed to invite prosperity for the coming year. Other Filipinos believe that eating twelve grapes on New Year’s Eve will ensure a year of good luck.

If all of this isn’t enough, many Filipinos get married in the months of December and January providing yet one more reason to cook large amounts of food and gather together with family and friends for a celebration. Essentially, Filipinos love any reason to eat and enjoy each other’s company!

How to Eat a Filipino Meal

Most Filipinos prefer to eat with their hands, especially in informal situations. Making sure their hands are clean, Filipinos always use the fingers of their right hand (even left-handed diners) to take a small portion of rice and to press it into a mound. A piece of meat, fish, or vegetable is placed on top of this mound and picked up with the fingers, and then brought to the mouth where the thumb is used to push the food into the mouth. It might take some practice, but this is the authentic way of eating Filipino food.

The Spanish introduced forks and spoons and, since then, their use has become widespread. The fork is normally held in the left hand and the spoon in the right hand. A knife is not normally needed since most foods are either pre-cut into bitesized pieces or tender enough to be cut using the spoon. The spoon is used to collect and then scoop up a mouthful of food while the fork keeps it from moving off the plate. Only in the most formal settings will you see a knife used. Although the Chinese left a lasting impression on Filipino food and culture, chopsticks are generally not used. Filipinos use a flat plate, making it impractical to pick up rice with chopsticks.

Another unique part of the Filipino dining experience is the use of patis (fish sauce) and bagoong (either sautéed shrimp paste or anchovy sauce) as condiments. These condiments (pampalasa) are used in soups, stews, and to accompany just about any dish on the Filipino table. Even when a dish is flavorful and well seasoned, a Filipino will still want to add patis or bagoong. So remember to put a small saucer or patis or bagoong on the table during mealtime if you want to keep your Filipino guests happy.

Meals are served family style—that is, they are placed in the center of the table with individual serving spoons, allowing each diner to take only the desired portion. Viands —the dishes that accompany rice—mostly have bite-sized slices of meat and vegetables.

Filipinos are easygoing and hospitable. They love to share their food! If you are visiting a Filipino home, you will definitely be offered helpings of local specialties—and if it’s fiesta time, you’ll enjoy even more.

Guests are treated with respect, but don’t start to eat until the host says so. Don’t hesitate to take a second or third helping as your host will be delighted that you’re enjoying the dishes. If you don’t like the food, try to eat a little bit out of courtesy. It is always important for guests to accept food offered by the host or fellow guests—never decline! Make sure you finish everything on your plate; otherwise the hostess will think you didn’t appreciate her cooking. Above all, enjoy the hospitality of family and friends while sampling the variety of textures and tastes found in Filipino cuisine.