Читать книгу An Unexplained Death - Mikita Brottman - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеII

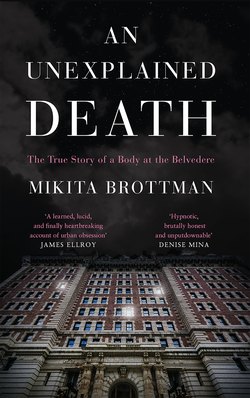

THE YEAR BEFORE Rey Rivera went missing, D. and I took possession of our newly purchased apartment on the fifth floor of Baltimore’s Belvedere Hotel. This grand building, whose doors opened in 1903, is one of the city’s oldest and best-known landmarks. It is 188 feet high, configured in a shallow “U” shape, with the opening to the south, and it stands at the corner of North Charles and Chase Streets, on the top of a hill overlooking the city.

Its architects designed the hotel in the grand style of the French Beaux Arts. The exterior, built of a beige-pink brick, has a two-story-high rusticated base and two cornices: one at the third floor and one at the eleventh. Graceful embellishments in terra-cotta— quoins, balustrades, a row of carved lion heads—adorn all four façades. At the top, elegant dormer windows project from a thirty-five-foot-high slate-covered mansard roof.

In its early days, this once-stately establishment hosted gala dinners for five hundred, grand balls, fireworks, symphony performances, dancing girls, kangaroos. Prominent jewelers, society dames, company presidents, traveling salesmen, bank chiefs, and clubmen all used the Belvedere as their Baltimore pied-à-terre. In 1905, on a tour of the East Coast, Henry James stepped off a train at the city’s old Union Station and took a horse-drawn taxi up Charles Street to the Belvedere, which he described as “a large fresh peaceful hostelry, imposingly modern yet quietly affable . . .”

Postcard from the Belvedere Hotel, 1906

At a cost of $1.75 million, this spectacular edifice was designed for wealthy tourists and socialites rather than the commercial travelers who make up the majority of the hotel trade, and while the restaurant and banquet rooms were always busy, most of the hotel’s three hundred luxury suites stood empty even as early as 1905. The Belvedere struggled financially from the beginning, with frequent changes in management and five different owners between 1903 and 1917. Only four years after it was built, it went into receivership and was purchased by the Union Trust Company for $1 million, including furniture and supplies.

Crowd outside the Belvedere during the Democratic National Convention, June 1912

In 1917, a popular and sociable fellow from Virginia named Colonel Charles Consolvo bought the Belvedere, still sinking in value, for $450,000. The rank was honorary—in 1913, Consolvo had been made a “colonial” on the staff of the governor of Minnesota—but he was a genuine hotel baron; among his other properties were the Monticello Hotel in Norfolk and the Jefferson Hotel in Richmond. A former circus clown, the colonel stayed in touch with his pals from the big top, and was known to impress the ladies by walking on his hands in the Belvedere lobby.

Consolvo owned the building for the next fifteen years; under his ownership and with the guidance of managers John F. Letton and William J. Quinn, the place finally started to turn a profit. This was also due to the war. Celebrities like Mary Pickford would come to the Belvedere to help sell war bonds, and after the opening of Fort Meade a contingent of dashing British and French officers, sent to instruct Americans in the art of modern warfare, would drink in the hotel bar in their off hours, attracting a steady stream of female attention.

Consolvo spent most of the year traveling on business; nonetheless, he took over the entire second floor of the Belvedere and stayed there whenever he was in town, along with his second wife, the former Blanche Hardy Hecht, an opera singer thirteen years her husband’s junior. When she was in town, this bohemian lady had the habit of walking around her rooms in the buff while singing the “Habanera” from Carmen (her mezzo-soprano voice was, according to the Virginian-Pilot, “smooth, and of good quality and range”). Accompanying this interesting pair was the colonel’s “mentally subnormal” “adopted” son (who may have been Consolvo’s natural child).

In Italy in early 1922, Mrs. Consolvo, thirty-seven, drew the admiration of Count Manfredi Cariaggi, thirty-two, a major in the Italian army. On May 8 of that year, she obtained a quickie divorce in Reno, Nevada, and was married in Fredericksburg, Virginia, five days later, thus progressing from an honorary American colonel to a real Italian count. She left with her new husband for Italy, sailing on May 23.

All ties between Colonel Consolvo and the Belvedere ended in 1936, and although it continued to operate under the able management of Albert Fox, ownership was turned over to the bank. In 1946, the financially troubled Belvedere was offered up in an arranged marriage to the Sheraton Hotel Corporation, making her the Sheraton-Belvedere. It was a match made for money, not love—nobody liked to see the grande dame becoming part of a corporate chain—but, like many arranged marriages, it worked surprisingly well. For the next twenty-two years, business was good and finances stable. The week before Christmas 1954, Albert Fox opened the doors to African-American guests. His decision was a bold one, but it was felt to be the right time, and business increased—despite pressure from the conservative Baltimore Hotel Association. Two months later, after media scrutiny, the hotel association changed its restrictive guest policies, and other hotels in the city gradually began to accept African-American clients.

Thanks to the proximity of Johns Hopkins University, the Belvedere has hosted some prestigious intellectual guests. The poet Marianne Moore arrived in Baltimore on a summer afternoon in June 1960. “Never felt such oven heat as in the taxi to the Belvedere,” she wrote to a friend. “I had waited in the sun but the hotel is very cool even with no air conditioner, which I turned off immediately. A better hotel than the Ritz in this respect; the coat hangers are not locked to the rod and the bathroom would satisfy Nero—either scented or unscented soap—huge towel racks peopled with bath towels—and on another wall, linen—well it is crucial.” Staying with Moore at the hotel were Margaret Mead and Hannah Arendt; the three women had come to receive honorary degrees from Johns Hopkins. (Afterward, Arendt described it as “an idiotic affair,” calling Moore “an angel” and Mead “a monster.”)

Magazine advertisement for the Belvedere Hotel, 1936

Six years later, over the weekend of October 18–21, 1966, Johns Hopkins again relied on the Belvedere to accommodate various academic luminaries, this time those attending the inaugural conference of the Johns Hopkins Humanities Center. Guests at the hotel that weekend included Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, Paul de Man, and Jacques Derrida, who, at age thirty-six, was just beginning to make a name for himself.

Upon his arrival at the Belvedere, then, Derrida was surprised to learn that the charismatic and far more famous Lacan had already taken the liberty of requesting a deluxe room for the younger man. Over a buffet dinner in the hotel restaurant that evening, the two Frenchmen finally got the chance to discuss their ideas, but quickly found themselves at odds. Their argument remained unresolved. Lacan, who still had not written his conference paper, went to bed, then got up very early and wrote as he sat at his window watching dawn break over the city. Those who attended the conference recalled that, while all the other speakers spoke in elegant French and relied on the talented translators provided by the university, Lacan insisted on using his terrible English.

“When I prepared this little talk for you, it was early in the morning,” the eccentric Frenchman began. “I could see Baltimore through the window, and it was a very interesting moment because it was not quite daylight, and a neon sign indicated to me every minute the change of time, and naturally there was heavy traffic.” He then declared, in a startling and bizarre insight, that “the best image to sum up the unconscious is Baltimore in the early morning.”

This gathering of luminaries provided a last moment of glory for the hotel; in 1968, Sheraton sold it to Gotham Hotels, Inc., which in turn leased it to a shady corporation that rented it out, in September 1971, as a dormitory for students at all the colleges and universities in Baltimore.

It was a stroke of genius that became a nightmare. Each university that sent students to the Belvedere assumed that the company would provide appropriate supervision for the hundreds of young men and women living in the old hotel, many of whom had arrived from small towns and were away from home for the first time. Their parents, who may have stayed at the hotel ten or fifteen years earlier, no doubt imagined their sons and daughters sipping tea in the John Eager Howard Room. But the truth could hardly have been more different.

It was the tail end of the 1960s, and the hotel dorms were coed and unregulated. There were all kinds of drugs and plenty of sex. Every weekend, all-night parties took place in the ballrooms, at which drag queens would mix with locals who had walked in off the street in hopes of picking up a shy young student. These festivities would attract local underground celebrities like the movie star Divine, as well as street hustlers and drug dealers who came to prey on fresh meat.

Those who lived through the four-month experiment all remember their majestic dorm rooms, the chandeliers, and the fancy furniture (although the meals, served in a cafeteria in the basement, were anything but fancy). The atmosphere was recalled as being pleasantly communal during the day, but it could get threatening at night. On the eighth floor, shy art students from the nearby Maryland Institute lived in uneasy harmony with the Morgan State University football team—a group of burly guys with little interest in abstract painting. The only supervisor anyone can remember seeing was a creepy guy with an artificial leg who was always hanging around at the parties, trying to pick up girls.

By the time the first semester was drawing to a close, things had started to get seriously out of hand. Fights broke out in the hallways. Two rapes were reported. The trash went uncollected. Police raids became regular events. By January 1972, the city had announced that the building would be closed because of extensive code violations, and everyone had to get out. Some of the students, angry at their sudden eviction, retaliated with vandalism, destroying their rooms and the hallways; others took along a few fancy lamps and end tables with them when they moved, mementos of the hotel’s former majesty.

Today, the Belvedere is a condominium complex. We live in an apartment that was originally two hotel suites, 501 and 502. The moment I laid eyes on the space, I fell in love with its shabby grandeur, the Swarovski chandeliers, the bare concrete floor, and the peeling paint. We’ve lived here for over ten years now, and our love is still strong. But as we soon discovered, there are drawbacks to living in a building constructed over a hundred years ago and designed as a hotel. The original kitchens are tiny, the windows almost impossible to clean; the air-conditioning system leaks, and until they were recently replaced, the elevators would regularly break down.

Thanks to its location and lack of outdoor space, the Belvedere is a quiet building, unsuited for families. Most of its inhabitants are older single people. Hardworking, quiet medical students at Johns Hopkins rent a number of the one-bedroom units, and there are a few older couples, like the two elderly ladies on our floor whom we see only on Sundays, when, dressed in matching wigs and hats, they make their way shakily to church. The grand ballrooms are owned by an events company, Belvedere & Co., which rents them out for weddings, rehearsal dinners, and other social functions. Enter the lobby through the revolving doors and you can still sense the old grandeur, but go upstairs to the residential floors and you will notice the carpets are worn, the light fixtures coated in dust.

In 1912, the Washington Post reported that an “Esthetic Nobleman” named Count August Seymore had planned to construct a “hotel for suicides” in the nation’s capital. This building, according to the count, would be a “haven for the depressed and weary of life.” Once the disillusioned guest had checked into his “eternal rest room,” taken the complimentary sedative, and pressed a bedside button to indicate his readiness, the desk clerk would discreetly turn on a gas tap in his room (thereby ensuring none of the furniture or carpets will be “spoiled by grewsome gore”). A crematorium on the roof would assist in disposing of the guests’ bodies, its furnace providing the hotel with a cheap and handy source of power.

Unsurprisingly, this imaginative scheme came to nothing, and the next time Count Seymore appeared in the newspapers, he was spending an hour a day in the window of a department store in Pittsburgh “demonstrating the correct method of wearing clothes.” Within a year he had moved on to a new obsession—the reanimation of the dead. Yet the count’s “suicide hotel” does make a certain kind of sense, if only in its acknowledgment of the fact that it’s much easier for people who want to commit suicide to do so in a private place away from home. And what place could be more private than a hotel?

This conceit forms the basis of The Suicide Club, Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1878 trilogy of short stories involving a secret society for those who “have grown heartily sick of the performance in which they are expected to join daily and all their lives long.” As one of the society’s members explains, “We have affairs in different places; and hence railways were invented. Railways separated us infallibly from our friends; and so telegraphs were made that we might communicate speedier at great distances. Even in hotels we have lifts to spare us a climb of some hundred steps.” The ultimate convenience—a key to “Death’s private door”—is provided to all members of the Suicide Club.

Outside of fiction, those seeking a key to “Death’s private door” will often register, with brave equanimity, at a hotel. There are various reasons for this, some emotional and others practical, but, to put it bluntly, at home people get suspicious. They want to know why you’re not sleeping, why you’re drinking so much, why you suddenly need a gun. Away from home, there’s far less chance of being interrupted. And even if they’re the reason for your suicide, do you really want your family cleaning up the mess?

According to a 2006 study by a pair of psychiatrists, the risk of suicide among hotel guests is much higher if they’re local residents. In some cases, suicide notes explain the choice of location. One man mentioned the desire to conceal the act from his daughter; another hoped to avert exposure in local media. In cases where no note is left, the authors assume the choice of a hotel is a way of “diminishing the chances of rescue and treatment.” Their study found that hotel suicides were slightly younger than average, but “maintained the male preponderance of suicide in the general population.” (The researchers also noted that suicidal men who are widowed or have never been married have less use for hotels, because “this population tends to live alone more frequently and could be less likely to need to implement strategies to reduce chance of rescue.”)

For hotel managers, dealing with suicide has always been an occupational hazard, though the cleaning staff usually bears its immediate impact. Casino hotels in particular have a higher than average suicide rate. More people kill themselves every year in Las Vegas than in any other place in America. The big Vegas hotels are suicide magnets—partly, though not exclusively, for those who’ve lost their life savings at the gaming tables. For this reason, most Las Vegas hotel rooms have neither balconies nor windows that open more than the inch or two that will permit the minimum required ventilation.

The suicidal leap has many advantages: you cannot change your mind, nor can you be interrupted halfway through; and, as long as the building is high enough, the jump is reliably fatal. In effect, however, the result of “plunge-proofing” Las Vegas hotel rooms has mostly been to drive would-be jumpers to a more public location, such as an interior atrium. In consequence, employees are instructed to be alert for guests who appear agitated and distraught, or for anyone lingering suspiciously in an elevated place. Such vigilance may appear altruistic, but human kindness is often simply a side effect of liability prevention. Suicides are bad for business, and in many cases, hotel proprietors can be held responsible for the damages.

According to an article entitled “How to Properly Respond to a Guest Death in Your Hotel,” published in a journal for hotel managers, one of the major problems of a hotel suicide is what the article’s author refers to candidly as “the gore factor.” “Think of a guest jumping from a balcony and landing in the atrium-style lobby or on the hotel’s sidewalk and I am sure you understand what I mean,” the author explains. “It will be messy and guests will be sickened if they witness the impact or see the impact site.” He goes on to suggest that hotel managers keep “very large dark-colored tarps made of impermeable material” readily available in case such a situation should arise, and advises that “management and security must uphold the utmost discretion in order to maintain some semblance of dignity for the decedent, the decedent’s family, and the reputation of the hotel.”

Today, people commit suicide in hotels for the same reasons they always did. While hotel managers rarely forget suicides on their premises, for obvious reasons they’re reluctant to release or even discuss statistics. However, Neal Smither, owner of the San Francisco–based company Crime Scene Cleaners, says that hotel and motel chains are his company’s biggest clients, and suicide cleanups provide most of his business. After Las Vegas, according to Smither, the region of the country with the most hotel suicides is the I-85 corridor between Alabama and the Virginias.

These days, it is companies like Crime Scene Cleaners, rather than the hotel’s housekeeping staff, that deal with the aftermath of suicides. Today, if a member of the staff encounters what appears to be a dead body in a hotel room, they are usually instructed to back out immediately and alert security. In most of the larger corporate establishments, staff members are given strict instructions not to speak about the incident. Once the coroner has arrived, the body has been removed (through the rear exit when possible), and the police have completed any necessary investigation, the room will be sealed and a professional crime-scene cleanup service brought in, with protective gear and special equipment, to make the room hygienic and presentable.

How long this takes depends on the method of death and the size of the room. Unfortunately for hotel owners, suicidal guests— since they know they will not be paying their bill—tend to choose large and luxurious rooms for their last night on earth. Most hotels err on the side of caution when such incidents occur, replacing the entire bed rather than just the linen and blankets, the whole carpet rather than just a stained rug; they may even replace drywall. Potentially hazardous material needs to be properly disposed of and the smell dissipated. Some hotels will bring in a priest to bless the room, not just for the sake of future guests but also for the benefit of housekeeping staff.

Unfortunately, small, independent hotels that don’t have the financial resources or moral accountability of the larger chains continue to rely on their own staff to clean up after such events. I learned this from a Reddit forum called “Tales from the Front Desk,” where hotel employees share their tales of pitiless managers, indignant guests, and grueling shifts at minimum wage. “A guy committed suicide on my shift,” recalls a hotel maid. “Once the owner found out about how much it cost for professionals to clean up deaths like that, he just had the maintenance guy flip the mattress.” A housekeeper describes how, in her first days on the job, a guest committed suicide using a gun placed under his chin while he was lying in bed. After the body had been removed, her boss asked for a volunteer to clean the room; wanting to make a good impression, she took the job. Before she went inside, she writes, a detective handed her two bags: one for any pieces of body matter she came across, and the other for the bullet, which was still missing. She did as she was asked, placing small scraps of flesh in a plastic bag while searching for the bullet (which turned up during the autopsy inside the corpse). “I still wake up from dreams where I am back in that room with those two bags,” she admits.

Even though larger hotel chains bring in professional cleaning teams to deal with the situation, coming unexpectedly upon a body is still a nasty shock. A desk clerk writes that he, his coworker, and his boss have all walked into guest rooms only to find “brains and blood everywhere.” A porter who works in a Washington, D.C., hotel recalls “a guy who broke down the roof door one night, jumped off, and landed on the second story, smashing into the window. In a room full of kids at 1AM.” Another desk clerk remembers how he “watched a jumper hit the ground from 20 stories up . . . I was traumatized.” And yet business must go on as usual: “Still I am expected to smile all night, preen like a peacock, and try not to cringe when some guy tries to dispute his adult movie charges that he clicked on ‘by accident.’ ”

In his well-known essay “The Jumping-Off Place,” first published in the New Republic in 1931, the writer Edmund Wilson described the Coronado Beach Hotel in San Diego as “the ultimate triumph of the dreams of the architects of the eighties,” contrasting its fabulous façade with the grim truth that San Diego had, for a time, become the suicide capital of the United States. The coroner’s reports, Wilson wrote, made melancholy reading, for they contained “the last futile effervescence of the burst of the American adventure.” In San Diego,

they stuff up the cracks of their doors and quietly turn on the gas; they go into their back sheds or back kitchens and eat ant-paste or swallow Lysol; they drive their cars into dark alleys, get into the back seat and shoot themselves; they hang themselves in hotel bedrooms, take overdoses of sulphonal or barbital; they slip off to the municipal golf-links and there stab themselves with carving-knives, or they throw themselves into the bay . . .

Those who come to the city to escape from “ill-health and poverty, maladjustment and industrial oppression” discover that “having come West, their problems and diseases remain,” and that “the ocean bars further flight.” These lonely visitors soon realize that the “dignity and brilliance” of exclusive hotels like the Coronado are intended for out-of-towners and convention-goers, not locals with little left to live for. For such people, the hotels’ cruel opulence is often the final insult.

I have tried to learn all I can about the suicides that took place in the former Belvedere Hotel. The brief accounts in early newspapers are compellingly suggestive. These vignettes of private tragedy are windows on the changing century; they refer to the introduction of automobiles, the telegraph, and the telephone; to the Great Depression, Prohibition, segregation, and revolutions in the hotel trade. Their casts of characters include alienated parents, sons with too much money, the lonely wives of railway tycoons, and businessmen suffering from existential angst. They evoke the genteel and bohemian Baltimore of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein, a prosperous city whose kings were Confederate generals, tobacco lords, and bootleg emperors. They reveal private crises and intimate tragedies that are even today rarely discussed outside the family, except in strained and awkward whispers. I find the suicide notes left by hotel guests especially touching, with their polite, self-deprecating apologies, their regrets to hotel staff for the necessary cleanup job.

Most of the Belvedere’s reported suicides occurred before 1946, when the hotel was sold to the Sheraton corporation. After that, it isn’t clear whether there were actually fewer suicides (this is certainly possible, since the Belvedere was no longer Baltimore’s highest building nor its fanciest hotel), or whether changes in reporting made it appear that way (suicides no longer made the papers unless they involved unusual circumstances or well-known individuals, or occurred in public places). It is possible that for a while, the Belvedere may have seen more than its share of suicides because it was often the first port of call for those who arrived in Baltimore to register as patients at the Henry Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, one of the country’s earliest and most sophisticated psychiatric hospitals. With its marble floors, its rose gardens, its private rooms with porches and fireplaces, and its spacious auditorium containing a pipe organ, the Phipps Clinic was considered the height of luxury for the nervously ill. It was where F. Scott Fitzgerald installed his wife, Zelda, in 1934, after her second breakdown (her doctor infuriated Fitzgerald by suggesting that he, too, could benefit from a course of psychoanalysis). The Phipps patients who took their lives at the Belvedere were mostly women; some did so before checking in to the clinic, some after checking out, and others while on a break from treatment.

Freddie Howard, currently the evening concierge, has worked at the Belvedere for over twenty years and has seen almost everything. This is a place where things happen, he tells me. Although there are rumors of ghosts, Freddie has spent hundreds of nights in the lobby and never seen or felt anything supernatural. There have certainly been plenty of deaths, including suicides, since the hotel became a condominium complex, but Freddie mentions only the two most recent examples he can think of. A gentleman hanged himself on the eighth floor last year. Freddie is not sure whether anyone ever knew the reason. A few years before that, Freddie recalls, another gentleman, on the third floor, cut his wrists over a failed love affair. He survived, but a few days later, he put a pillow over his head and shot himself.

The second time, he got it right.