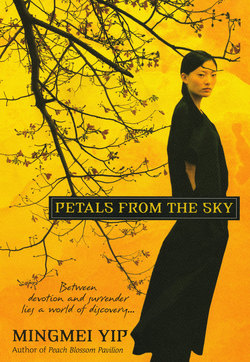

Читать книгу Petals from the Sky - Mingmei Yip - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 The Fall

ОглавлениеIt was the day after my thirteenth birthday. Father had just lost five thousand dollars in a casino in Macau, forcing our family to move from Tsim Sha Tsui, the bustling commercial district in Kowloon, to a village house in remote Yuen Long. The rent was two hundred Hong Kong dollars, three times cheaper than what we’d paid in the city.

In the communal backyard behind our house was an abandoned well surrounded by tall grass that whispered when the wind blew on winter nights. Older villagers avoided the well because there were rumors that ghosts dwelled in it. A hundred years before, a young concubine, with a stone tied around her neck, had jumped down the well to prove her innocence after being accused of having an affair with a wandering monk. People believed the well was so old that it had absorbed the essence of the sun, moon, stars, water, air, wind, sound, and light until it acquired a spirit of its own. A blind fortune-teller insisted the well was the third eye of an evil goddess who would observe the people above and snatch down the handsome ones—especially children—to feed her jealousy.

While children were warned to stay away from the forbidden opening, the younger adults didn’t care about it one way or another. They simply regarded the well in a practical way—as a trash bin.

As for myself, the myth pricked my curiosity during my lonely adolescence. I’d sneak to the well and stare down into the space below. Most of the time what I saw was completely different from the villagers’ descriptions. Rather than frightening, I found it fascinating. In the dim light, I could make out all kinds of objects—blankets, books, branches, twigs, papers, clothes—thrown down through a gaping hole in the mesh that covered the well’s mouth. I imagined a diary hidden among the piles of refuse, words inscribed on tear-streaked rice paper in vigorous calligraphy by the doomed concubine to bitterly lament her innocence. I also imagined photographs, faded and brownish, of forgotten people. A young bride, a happy family, the sad-faced concubine with her bald lover, a chubby baby with eyes widened as if asking: why was I thrown into this cold world?

During days of heavy rain, water would rise from the bottom and I’d see my own reflection with a small, round piece of blue sky floating behind my head. Sometimes I’d hear noises whispering below when the wind stirred the long grass aboveground. One evening I saw the reflection of the moon, so round and pregnant that I thought she might burst and drop into the well and make a splash so loud it would wake everybody from their dreams.

On other evenings, I saw stars peeking shyly at their own images. I would throw down a stone and watch the reflection split into tiny diamonds, like those that had once sparkled on my mother’s pretty fingers. I imagined time itself reflected on the circle of water and, like a kite snapped off from its string, flying away through the opening, carrying away memories of color, smell, and touch.

Whenever I peeked into the well, I felt the evil goddess also staring back at me, her eye hidden. She’d watch my every move and absorb my heart’s deepest secrets. She made me see—by linking the earth and the sky together—another world, familiar yet strange. She was the third eye connecting me to a larger, mysterious universe.

I’d always wondered how it would feel to be on the other side of the world.

One hot September afternoon as I studied, my parents began to fight over my father’s purchase of a pair of expensive shoes. Mother said he would rather feed his vanity than his family. He argued that a poet must retain his dignity. As my parents’ voices began to simmer and boil, I sneaked out to the backyard, went straight to the well and looked down, wondering what I could find this time to cheer me up: a book, a pillow, a doll, a puff of cloud floating in the sky? But in such dry weather I saw nothing except darkness. I looked up and met the angry glare of the sun.

Just when I began to feel uneasy and thought I should go back home, someone bumped me from behind. I lost my balance and plunged into the dark. I didn’t know how long I’d been unconscious, but I woke up surrounded by a fresh coolness. Yet my head ached and my body was clammy with a cold, searing pain. My clothes were torn, my knees badly scraped, and my toes swollen like sausages. But I was alive! The trash in the well had cushioned my fall and saved my life. I kept thinking how ridiculous to be saved by a heap of rubbish. I could have laughed, except my joints throbbed as if on fire.

I looked up toward the dim light and saw blurred faces leaning over the well, staring down and howling, “Meng Ning, can you hear us?” “Are you all right?” “Don’t be afraid; we’ll get you out as quickly as possible!” I could hear my mother crying and see my father holding her tightly in his arms. The world above looked remote and alien. The people, yelling and gesturing wildly, seemed trapped in the circle of clear, blue sky.

But I was the one who was trapped. I tried shouting back, but the darkness, like a witch, snatched away my breath and swallowed my voice. My chest swelled and my heart jumped like ants in a hot wok. My knees were cut and sore. I wrapped some old dirty rags around them to stop the bleeding. I asked myself if it would be my fate to die, rotting with the garbage, in an obscure hole in the earth. The walls around me exuded the smell of decay and rotten fish. I reached out to touch the stone lining of the well, but immediately withdrew my hands when I felt a stickiness like the blood on my knees. I wanted to cry, but no tears came, only gasps.

I looked up again; people were still leaning over the well and looking down at me, with flashlights and kerosene lamps raised high in their hands. Their loud voices carried down to me, but I sensed hopelessness behind their frightened faces. I could almost see them cupping their mouths and whispering, “A doomed child, what can we do?”

Suddenly, I thought of the Guan Yin statue in my neighbor Mrs. Wong’s house and of how this plump woman used to ask the Goddess of Mercy to protect her ancestral graves, give her a son, even cure a cold. She’d kneel before the serene ceramic figure in its small shrine surrounded by lighted joss sticks and offerings of flowers and fruit. Then she would press her hands together, kowtow, and pour out fervent prayers. Now, imitating her, I put my hands together and whispered an ardent prayer to Guan Yin, pleading to her to get me safely out of the well.

I kept praying, ignoring the talking, arguing, and crying above, and the strong odor of vegetation, mildew, and rot surrounding me. Then something grazed my head and landed beside me on the ground with a soft plop. I picked it up and held it to the side of the well where the light was brighter. From a thin red string dangled a brightly colored Guan Yin pendant. The Goddess of Mercy wore an orange robe; her hands held a flask with a willow branch and her bare feet rode on a big fish that looked as if it were swimming toward me.

I felt a tinge of warmth.

I looked up and glimpsed my parents’ concerned faces. Mother was still sobbing; Father pulled her close to him. Other faces squeezed to lean over the well, looking down while competing with one another to offer comforts and suggestions. I frantically waved the pendant at them, then cupped my mouth with my hands and yelled at the top of my voice toward the opening, “Mama! Baba!” Suddenly hearing that I was very much alive, people got excited all over again. A child clapped. Several old people pressed their hands together and whispered prayers. Teenagers raised their index and middle fingers to show victory. My parents squeezed through the crowd to peek down at me. “Oh, thank heaven, Ning Ning, are you all right?!” Mother hollered and Father kissed her on her forehead, their earlier quarrel forgotten. Then, with my blurred vision, I saw a bald scalp above a pretty face, glistening in the sun. I blinked and strained, but the scalp and the face were no longer there.

The crowd continued to lean over the well, taking turns to keep me company and to throw down a blanket, a sweater, candies, cakes, even several comic books.

Everybody was talking to me to keep my spirits up. One old neighbor yelled, “We’ve called the firemen; they’ll be here any minute!” Another hollered, “We’re getting ropes and a basket to get you out!”

So I sat and waited with Guan Yin in my hand and all the people watching from above. The air was dense yet soft. I kept praying to the Goddess of Mercy until I felt my prayers deep underground and my fear dissipated. My hands pressed together and my lips moved as though I’d been practicing the ritual for a thousand years.

It was very strange, but I had begun to like this small world of my own. The rancid smell ceased to bother me. In fact, I felt soothed by the strange coziness of this space, now completely mine. I could almost feel the wall breathing faintly and wrapping close to me, the trash and withered foliage moving gently and warming my body. I listened to the well’s pulse beating with mine and felt a stab of gratitude both for my privacy below and for the care of so many people above.

When the villagers were ready to rescue me, they threw down more quilts. Voices shouted, “Meng Ning, spread them out under you!” Then came the long rope and the basket. The voices hollered again, “Get in!” Slowly, I climbed inside and curled up like a baby in the womb. The people above began to pull. The ascent was slow, cautious, wobbly at times, but steady. People kept yelling, “Meng Ning, don’t look down!”

But I couldn’t resist the temptation. I wanted to take one last look at the little round corner that had unexpectedly given me moments of peace. So I leaned over and looked down. I didn’t panic as the villagers had feared. Instead, I felt great tenderness for a larger realm that I couldn’t yet name. I recalled the reflection of the floating clouds in the shimmering water, the third eye forever following me when I moved, the pregnant moon, the peeking stars, the murmuring tunes of the grass at night….

Then I was suddenly in daylight again, being pulled out of the basket by my parents, who were crying and shouting, “Oh, Ning Ning! Thank heaven you’re okay!” All the neighbors took turns to comfort and greet me. Right then, the firemen arrived. I was immediately rushed to the hospital for a checkup. The doctor said besides a few bruises and cuts, I was fine, and miraculously, not a single bone was broken. He bandaged my knees, gave me a tetanus shot, and said I could go home.

After that, I was considered an extremely lucky child. The blind fortune-teller said any person who had survived such an ordeal could only be a reincarnation of Guan Yin. The villagers held a celebration party for me the next day. They made offerings to the ancestors and gods, then they roasted pigs, butchered chickens, gutted fish, warmed wine, and ignited firecrackers. They also showered me with gifts: lucky money in red envelopes, clothes, toys, books, crayons, my favorite Cadbury Fruit & Nut milk chocolate, first quality tea leaves, wine, even gold and silver ornaments, and small antique statues. My parents’ hands were intertwined during the whole evening, their eyes resting tenderly on me.

While I was pampered like a little princess, the two boys who’d knocked me down the well during their game of police-chasing-thieves were severely punished—each had his bottom whacked ten times with a thick stick. My plea that I actually had a good time down in the well landed on deaf ears. The villagers thought I was just being nice and adored me all the more. My neighbor Mrs. Wong gave me the best Iron Goddess of Mercy tea with rose petals, and a roasted chicken like the one she had offered to Guan Yin. Believing that they’d share my good luck, several villagers went to buy lottery tickets. After the banquet, my father took all my lucky money and slipped out to the gambling house.

I almost wished I would fall into the well again, so that Father would stop gambling and fighting with Mother. So I’d always be loved and treated like a goddess. So I could be left alone with just Guan Yin in that quiet place underground.

A few days later, I ran into Mrs. Wong. She told me that near my house was a nunnery dedicated to Guan Yin; she regularly went to pay her respects to the gilded Guan Yin statue sitting on a golden lotus. I soon began to visit the temple after school. Surrounded by glimmering candles and the fragrance of long-burning incense, I’d look up and pour out all my heart’s troubles to the Goddess’s beautiful image. I’d also watch the nuns’ kind faces as they housed and nurtured the orphans, fed the poor, cared for the old, prayed for the dead. Like Guan Yin, the Goddess of Mercy, they plunged into the Ten Thousand Miles of Red Dust—the mortals’ field of passion—having sworn never to enter paradise even if only one soul was still left unsaved.