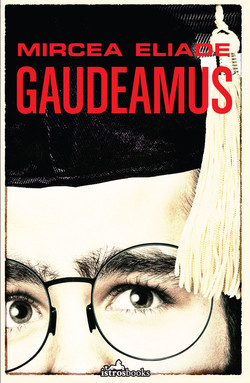

Читать книгу Gaudeamus - Mircea Eliade - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTWO: THE CHAIRMAN

I finished that autumn, alone. And then, all of a sudden, in early December, the attic came to life. Evening fell, but upstairs, in my attic, choirs intoned. It had all happened so fast – I am beginning to forget exactly how I came to meet the doctoral student with the broad forehead and nervous smile at the corner of his thin lips. He explained to me, walking down the boulevard, how the city did not yet have a student association, how at the university year after year passed without anyone attending or establishing one. An older gentleman wished to donate his fortune for a students’ club, if only an association existed, but there was no association, because students were happy to spend their years with old friends to whom they were connected by childhood or lycée. If only a room could be found somewhere, a room in which to organise.

‘I have a attic.’

The doctoral student demurred; young men and women are noisy, unruly. They would disturb and annoy whoever else might be at home.

‘But the attic is mine.’

He consented, but only for the choir. Happy, we went our separate ways in the night. The next morning, he climbed the wooden stairs and knocked on my door.

‘So many books, so many books.’

He told me everything he had done since we parted; he had recruited five friends to form a committee, written an appeal to the city’s students, taken receipt of the first funds from the old gentleman, and ordered membership cards from the printers. Medical student that he was, he gauged the volume of air in the room.

‘No more than two hours, for fifteen people. After two hours we’ll have to open the windows.’ He had been wanting to announce a student assembly in the newspapers, but had not found a room large enough. I quickly put on my coat, and together we set off to visit the headmaster of the lycée.

The old man attempted to be nostalgic: I had first arrived there nine years ago, a small, shy boy, but look at me now: a university student! Did I still recognise my old headmaster, the parent of my adolescent soul? The doctoral student bit his lips in impatience. But what good was any of this now? A new, fruitful and dynamic life was beginning. Could he lend us a helping hand? Would he agree to let us use the music hall for our first few meetings?

‘For university students, naturally.’

The student thanked the headmaster briefly but warmly, then left, heading for the university, the newspapers, the dean’s office, the cafeteria.

On my way back, alone, with bitter memories of the headmaster in my soul, I encountered the first snowflakes of the season.

‘December.’

Two days later, my little windows were lit blue by the snow. In my room, it was cold and dark. I brought up loads of coal and wood, dusted white. Sitting by the stove I read, in disbelief, the announcement in the columns of Universitare: ‘Today, at five p.m., students of the university who wish to join the city choir are invited to enrol at the provisional headquarters in the attic of.’

I ran downstairs.

‘We’ll be having guests at five o’clock.’

‘How many?’

‘I’m not sure; twenty or thirty. But we’ll be holding auditions – some will be leaving almost as soon as they arrive.’

Mother did not believe that I would be having ‘guests’ until she met a girl asking for directions.

‘Excuse me, is there a attic here, some kind of provisional headquarters?’

As luck would have it, it was Bibi. The doctoral student had not yet arrived. I was nervous and wondered if it was warm enough, if the armchairs were comfortable, if the bookshelves were tidy. Bibi had not expected to see me or, even more so, to see me there all by myself.

‘Are you the only one here?’

‘Yes, I am … well, you see.’

‘Ah, so this is your attic.’

‘That’s right.’

An awkward silence.

‘You were working when I arrived; let me take something to read, something from here.’

She took a copy of Corydon. I blushed.

‘Is it any good?’

‘It’s interesting.’

‘A novel?’

‘No. Gide.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Haven’t you read anything by Gide?’

‘Yes I have. A textbook: The Political Economy.’

Charmed, I explained, ‘That’s by Charles Gide.’

‘Oh! Sorry! And this is by Andrei.’ She smiled, looking through the book.

‘I know somebody called Andrei, a polytechnic student. He skis.’

I nodded.

‘Yes, yes.’

I invited her to sit down in an armchair between the bookcases.

‘Don’t you get bored up here all alone?’

I lied, presumptuously.

‘I wouldn’t say I’m alone, exactly.’

She took a long look at me.

‘That’s strange; you don’t look like someone in love.’

Pale, very pale.

I was saved by the doctoral student; he entered without a word, with a bag, damp from melted snowflakes, his forehead red from the cold.

‘Aren’t you going to introduce me to the young lady?’

How was I supposed to introduce her by her nickname, Bibi? But she introduced herself. I made a mental note of her name.

Within half an hour, the attic was full of students. The provisional committee assembled at the table. I recognised a few of them. Two from the Polytechnic: a second-lieutenant in his final year at medical school, and a stooped, skinny young man, who smoked copiously and weighed his words carefully. The others were strangers. There were only a few girls; they sat on chairs and the bed. We listened to what the chairman had to say.

He was not a gifted orator. He struggled to find the right words, but when he did find them, he delivered them resoundingly. He reminded us of the old gentleman’s donation. But the association did not yet exist. It would have to be established as soon as possible. The choir and the festival would bring in funds. We would sing carols for government ministers, for the dean of the university, at the royal palace. The association would have to be officially registered. That way, we would be able to receive donations. At the same time, we had to foster ‘the student life’.

My guests were inspired. They promised help, work, with enthusiasm.

‘And discipline’, added the chairman.

A young man with black hair was appointed choirmaster. Flattered, he asked to hear everyone’s voice. The girls protested.

‘We’ve been singing since lycée.’

The boys teased, ‘Then it’s been a long while, hasn’t it.’

A pale, quiet girl capitulated.

‘Do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti!’

A tall, swarthy, thick-lipped student, who stood leaning against the door, opined: ‘She’s a tenor.’

Laughter. The girl turned red, and shrank back apologetically. The chairman interjected, ‘Gentlemen, you promised.’

A young woman, with dark, sunken eyes, moist lips, and trembling nostrils spoke up. She had wavy, neck-length black hair and her arms were bared to the shoulder.

‘Chairman, sir, they should go first!’

The boys protested, suddenly nervous.

‘Ladies first.’

‘The boldest first’, replied a blond girl.

Amid this hubbub, I took a look around my attic: Cigarette smoke, the smell of women’s clothing, shadows. The bookshelves paid silent witness.

Above the headboard of my bed, the dried willow garland around an icon shed its dry leaves. I felt so happy and such a stranger!

The chairman’s ruling solved the dilemma: ‘The girls will sing scales, and the gentlemen will go downstairs and wait in the courtyard for a few minutes. Make sure not to break any windows!’

I could hear them plotting.

‘But we’ll catch cold.’

The girls agreed to go first, but only if the boys promised to behave themselves. The young lady with the dark eyes gave a perfect, defiant rendition of the scale.

‘Your name and faculty?’

‘Nonora – Law, and the Conservatory.’

The boys ‘Aha!’

Two days later, rehearsals began. The young women one afternoon, and the young men the next. This arrangement was not to the liking of the men. They arrived late, smoked, and ignored the chairman. It was decided to hold joint practice sessions. The men arrived half an hour early. Some politely asked me to forgive the intrusion. They began to discuss the student strike. Some were for it, others were carried along with the tide, and others still were against it.

‘And what do you think?’

I did not want to think anything. I listened. When the first young lady arrived, the discussion grew impassioned.

‘Sexual selection’, I said to myself.

The women complained to the chairman about the men ‘talking politics’. The chairman banned any further talk of politics, as it was conducive to disorder. If the men in the room wished to discuss such matters elsewhere, they were perfectly free to do so.

We rehearsed Gaudeamus igitur – a certain feeling descended into the attic, amid the cigarette smoke and the books, a feeling of Heidelberg coming to life. It was hot between the white walls, we were happy that it was snowing outside, that it was snowing heavily. Our voices resounded through the windows and enlivened the street. The women had befriended each other. They huddled around the tiled stove, and leafed through German books in fascination. I divined how, evening after evening, they were becoming more drawn to the attic. In the beginning, they had voiced concern about entering so small a room, without rugs, and with so many bookshelves and burning cigarettes. But it was so novel, so unusual. They then found themselves starting to look forward to our rehearsals. It was ‘pleasant’. Perhaps they were dreaming, perhaps it reminded them of novels, or perhaps they were hoping.

Nonora was becoming more and more forward. But she was still undecided. She smiled at all the men and received never-ending compliments from admirers who cast furtive looks at her knees, breasts, shoulders. She annoyed the women because every night she positively demanded a gentleman walk her home. Even the chairman was charmed by her. In discussions he now began to ask her to take the floor: ‘And what does Miss Nonora think?’

One afternoon, I saw her standing at the top of the stairs after being kissed by a dull but handsome student.

‘You’ve got a cheek! You’ve wiped off all my lipstick.’

‘Is that all?’

She and Bibi had become friends. They came to rehearsals together.

‘Who will help me take off my wellingtons?’

Maybe she was speaking to me as well. Five tenors bent down to assist her.

‘Wait a second, wait a second! Just my boots.’

She liked Radu. She met him one evening at my place, maybe what she liked in him was his ungainliness, his cheerful shortsightedness, his cynicism, which was that of a man who submits to fate. Radu was the only friend who had not abandoned me in the autumn. I met the others only seldom, and when I did, we talked about insignificant things. They were furious that I had hired out the attic to a club of strangers.

‘Before long you’ll turn into an anti-Semite, too.’

We preserved the same closeness when we talked, but I was looking for new friends. Radu might as well have been a new friend. After we had gone our separate ways, in him I had discovered very many qualities that nights spent drinking in taverns had not managed to destroy.

And Radu came to my attic every night, once he found out that Nonora came too. He alone walked her home now. Nonora liked him best of all the students, because he was intelligent, cynical and ‘witty’. The others were handsome and vulgar. Nonetheless, she continued to let herself be embraced by any who dared. She kissed with open lips, her head thrown back. And she would complain afterwards about ‘the savages wiping off all my lipstick’.

Bibi introduced me to Andrei, who was tall, dark, broad-shouldered, and had a look of hard-working ambition about him. He wanted to become a chief engineer. Intelligent and voluble, he pretended to be curious about science, but found it difficult to conceal his ambition. After all, he did want to become a chief engineer. It seemed as if Bibi loved him. She asked me two days later what I thought of him. I praised him, of course. Bibi had given herself away.

‘Did you see his eyebrows?’

At the very first meeting I met a multitude of students. They couldn’t believe all the chairman’s promises: the officially registered body, the student club, the holiday camp. But even so, they felt happy to be in that music room with so many beautiful girls and intelligent boys. The chairman had managed to obtain the signature of the university rector for an official charter, a grant from city hall, and a permit for a carol concert, festival and raffle. His briefcase was always stuffed full and he was always in a hurry. In less than twenty days he had formed a recognised student organisation, had registered members, had found a provisional headquarters, and had delegated the workload to committee members. At the same time, with white lab coat and furrowed brow, he was preparing his thesis on balneology.

The members were thankful to him for one thing: he had given them the opportunity to get together and enjoy themselves. The tall student, who always stood next to the door was known as ‘Gaidaroff’. He was the only one to interrupt the proceedings of committee meetings without being called to order. The members were fond of him, and pelted him with snowballs after every rehearsal.

At the second meeting, dues were paid. To my surprise, no one protested. After the meeting ended, we all went to the football pitch next to the lycée for a snowball fight. We threw our snowballs with great gusto, especially in the direction of the chairman, who banned the wearing of gloves and the throwing of snowballs containing stones. We chose sides in a matter of minutes. Nonora battled to the right of me, shielding herself with a briefcase, shrieking, taunting, cursing. Bending down to make a snowball, I felt snow on my neck and hair. Nonora cackled defiantly, with her head thrown back.

‘Traitor!’

‘The name’s Nonora.’

‘What if I get my revenge by burying you in the snow?’

‘Burying me alive? I was only joking. You’ll forgive me.’

I shivered. It was getting colder. There was a spring in my step as I went home. I felt like breaking into a run. In the attic, I gazed into the mirror for a long, long time. I decided to let my hair grow long, groom myself, buy white collars.

I read, but my soul no longer belonged to books. With a pencil, I made notes on paper about what I had gleaned from the books, what they made me feel. I worked as if fulfilling a duty, or out of a sense of obligation. I spent less time thinking about myself. I avoided analysing myself, questioning and answering myself.

Now that I had abandoned the discipline of keeping a diary, I indulged in daily self-contradictions. I no longer pursued private thoughts. School work no longer caused me anxiety. I shut it away in my brain the moment rehearsals began. I was experiencing a new and tempting life. Day after day I discovered techniques to help girls with their clothes, how to respond modestly and politely to compliments about my library, how to smile, how to soften the severity of my looks.

The austerity of adolescence had dissolved with that autumn. With gratitude, I forgot the anxieties that had previously cut my nights short. I relinquished the ambitions whereby I had survived lycée. I felt so happy to be in my attic full of young men and women. I whiled away more and more nights with Radu. We talked about Nonora. He had kissed her; passionately; biting her lips. I pretended to be indifferent, preserving the mask of my old soul, which was crumbling without my fully understanding the circumstances.

I woke up later and later every morning. I sat down at my table like a labourer waiting for the factory whistle. I read and read. You would have thought that someone was forcing me to write summaries of certain titles. I summarised them properly, without rushing. I packed the summaries away in boxes. And I caught myself thinking thoughts impudently inapposite to my card catalogue.

After the night of carol singing at the Orthodox Patriarchate and the Royal Palace, we crammed into large motorcars. The girls were wearing traditional costume. We were flushed with the wine from the Patriarchate, drunk with success. And the King had asked each of us: ‘Und you?’

‘Industrial Chemistry, your Majesty.’

There had been a feast fit for a boyar at the Patriarchate. And then there was Gaidaroff, who had asked how many of the cigarettes we could put in our pockets, and Nonora, who had choked on a noodle, and the chairman, who had laughed merrily, sipping glasses of red wine, and the choirmaster, who had congratulated us.

We were in in even higher spirits when we sang our carols to the three ministers, the philanthropist, the newspaper proprietor, and the dean. After midnight, the motorcars dropped us off in front of an unfamiliar courtyard. It was a surprise from the chairman: a banquet room, at a friend’s, with preparations for a party until morning. Exclamations, disbelief. I ended up sitting between Bibi and Nonora. Bibi found a greetings card envelope and amused herself by writing questions on the back. ‘Who are you thinking about?’ Nonora answered: ‘About someone who ought to die.’ I added: ‘When?’ Nonora wrote: ‘Now.’ Bibi was perplexed: ‘Why?’ I quoted the line from Coșbuc: ‘Question not the laws.’ Nonora: ‘You’re hilarious.’ Bibi: ‘Is that all he is?’ Me: ‘And also tortured.’ Nonora: ‘Liar.’ Me: ‘You guessed right.’ Bibi: ‘Prudence is the key to happiness.’ Me: ‘Really?’ Bibi: ‘What impudence!’ Nonora: ‘Kiss and make up.’ Me: ‘There isn’t enough room on the envelope.’

Towards morning, with the snow frozen under the stars, I agreed to walk the ladies home. The night had passed so quickly – couples were now well-established, and tossed pointed jokes back and forth. Gaidaroff smoked all his cigarettes sitting next to a girl, a pharmacology student, a petite girl with roguish eyes and enticing breasts. With feeling, the chairman declared from the head of the table: ‘Ladies and gentlemen …’

The boys replied with enthusiasm: ‘Vivat profesores.’

Bibi, smiling, said: ‘I should.’

A blond girl said: ‘That made me hopelessly sad. It’s time to go home.’

Nonora: ‘I’m bored. Radu, go fetch my overshoes.’

Radu had suffered the whole night, stuck between two girls who spoke only to the people sitting on their other side. He was happy when Nonora called for him. He walked her home, arm in arm. I walked Bibi home and searched for phrases in which I could address her as tu without blushing. I succeeded.

*

Days filled with life. Self-doubt and consternation failed to find their way into my soul. I was happy at the beginning of that white winter.