Читать книгу Along the Bolivian Highway - Miriam Shakow - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

The Intimate Politics of New Middle Classes in Sacaba

Doña Saturnina Ramírez was in her late sixties in 2013, a plump, formidable woman.1 She had many godchildren, evidence that she was held in high esteem by many people in her hometown of Choro, even as some of Choro’s poorest residents were intimidated by her sometimes severe manner and by her children’s astounding professional achievements. Doña Saturnina’s family trajectory illustrated the sudden windfall that the coca boom had meant for many Sacabans. She wore a full pollera skirt and her hair, streaked with gray, in two long braids. As a chola in early twenty-first-century Bolivia, she identified herself as rural and campesina. Three of her four daughters, meanwhile, wore jeans and straight skirts and identified themselves as professionals. Seven of her thirteen children had died in infancy or early childhood of the gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases that afflict the very poor; five of her six living children, by contrast, had earned professional degrees or were attending university.

Like Marisol the pharmacist, Doña Saturnina’s children described themselves as an island of professionals amid a sea of campesinos in Choro. They often declared, “We are the only family in Choro in which all the children have studied.” While other local families had, in fact, produced several university students or graduates, many Choro residents echoed the family’s refrain about their uniqueness. They marveled at Doña Saturnina’s ability to raise a brood of “all professionals” (puro profesionales) or grumbled that Doña Saturnina’s children were snobbish (creídos) because they were professionals. Edgar, the eldest and in his forties in 2006, was a lawyer. Deysi, the next eldest, was a rural high school math teacher with a master’s degree from a prestigious private teachers’ college, while her younger sister Amanda was a lawyer. David was a pediatrician. The youngest, Celia, was nineteen and studying for an architecture degree. The refrain, “all of us have studied” excluded Julia, in her mid-thirties, a coca farmer and small-time cattle rancher before she set off for Spain (prior to the Spanish recession of 2008) to work as a home health aide. Doña Saturnina’s children spoke to each other at home in Quechua, Bolivia’s most common indigenous language. Yet like many speakers of indigenous languages in Bolivia and other Andean countries, they did not (usually) identify themselves as indigenous (see Canessa 2007; García 2005; de la Cadena 2000).

Doña Saturnina’s family, like Marisol and many other residents of Sacaba Municipality, struggled to establish and maintain a middle-class position in Bolivian society. They held fierce ambitions for their family’s prosperity and social mobility to “get ahead” (salir adelante). The coca boom sparked these ambitions among many in the Cochabamba region, inspiring them to shift their dreams to upward mobility through education or commerce rather than through agriculture, to imagine a future as a professional or affluent entrepreneur rather than a campesino. These middle-class dreams were coupled with intense anxiety, however, in part because they feared skepticism from wealthier or more highly educated people. They also faced equally vexing accusations of selfishness and snobbery from poorer and less highly educated friends, family members, and neighbors. My term “intimate politics” highlights both the prevalence and intensity of power struggles occurring at this most personal of levels between close family members, neighbors, and friends. Struggles for belonging and companionship, competition for social supremacy between husbands and wives, sisters and brothers, friends and neighbors grew from long-standing hierarchies of class, race, and gender in Bolivia as well as uncertain prospects in the free-market, post–coca boom economy.

In this chapter I look in detail at these intimate politics and the broader conflicting moralities that surrounded them, based on conversations with members of two dozen upwardly mobile extended families with whom I became close during my research. They included logging company owners, truckers, market sellers, cocaine producers, and, among younger generations, teachers, lawyers, agronomists, and doctors. I also draw upon years of conversations with people frustrated at their own poverty. I focus particularly on the experiences of Doña Saturnina and her grown children because the diversity of their perspectives and my long-term relationship with them provides a window onto the experiences of conflicting class and race identities that characterized new middle classes in Bolivia and, I suggest, in much of the Third World.

Doña Saturnina and other members of Sacaba’s provincial middle class attempted to assert their distinction as upwardly mobile through their moral virtue—hard work, sexual propriety, thrifty money management, and high academic achievement. They also sought to avoid accusations of snobbery or of having profited at other people’s expense “from the ribs of others” (a las costillas de otra gente). Envy was a common language for talking about conflict over inequality; discussions of envy marked the clash between ethics of individual upward mobility and ethics of equality. In practice, in their intimate lives, they espoused alternating ethics of social equality and superiority.

Upward mobility for people in Sacaba provoked anxiety, in part because the language of race and class was polarized between binary oppositions—of wealthy and poor, indigenous and nonindigenous—in ways that left little space to assert an intermediate wealth and social status. As in Marisol’s account in Chapter 1, the prevailing characterization of Bolivia was that of a society split between a dominant white elite and marginalized indigenous majority; there were few words in Sacaba through which people could identify themselves in any way as “in the middle” (compare to Liechty 2002; O’Dougherty 2002). More commonly, they alternated between elite and subaltern terms of identity, alternating, for example, between calling themselves profesionales and campesinos or rarely, indígena (indigenous).

Newly prosperous people in Sacaba often defined their identity in relational fashion, depending on the social context. This dynamic was similar to that of cholas for most of the twentieth century in Bolivia, who took on working-class and Indian identities when confronted by social superiors, and local upper-class and white identities when talking to social subordinates (see Weismantel 2001; de la Cadena 2000). Many newly prosperous Sacabans shared aspirations for upward mobility, fierce social competition, the practice of drawing moral distinctions, anxiety about their social position, and a sense of social fluidity with middle classes in many places in the world (Liechty 2002; O’Dougherty 2002). At the same time, they also shared the experience of relational identity and the alternation between binary opposites of elite and subaltern race and class with people who inhabited the Andean social category of the chola. That the language of class and race in Bolivia did not fit their actual middling economic and social experience added an additional layer of ambiguity about their status in social life.

Doña Saturnina’s family narrative of escaping campesino and Indian status was emblematic of many Sacabans’ aspirations for upward social mobility as individuals and families and contrasted with the MAS party’s formal rhetoric of collective uplift as indigenous campesinos. Doña Saturnina’s children told me that their parents had worked single-mindedly for many years with the sole aim of sending them to college to escape the everyday social stigma of Indian and campesino identity. They repeatedly recounted a pivotal moment in their family’s history when a policeman had yelled viciously (abusado, maltratado) at their father, Don Prudencio, who felt powerless as an uneducated man to shout or fight back. Don Prudencio reputedly vowed at that moment, “My children need to study and become lawyers to defend themselves.” He and Doña Saturnina thus described their quest as aimed at upward social mobility, an escape from the humiliation of social subordination, as much as material prosperity.

Don Prudencio had earned a decent income while working throughout the 1960s and early 1970s as a driver for a wealthy truck-owning relative. But after several trucking accidents left the family in debt, Doña Saturnina and their children forbade him to drive. The price of coca and cocaine was just then booming, in 1975, and so Don Prudencio and Doña Saturnina decided to turn their efforts toward growing coca in the tropical Chapare region, seven hours away. Over the next twenty years, Doña Saturnina and Don Prudencio put four children through university largely on the proceeds of their coca farming. They were helped by the veteran’s pension of Don Prudencio’s mother, whose late husband had fought in the 1932 Chaco War with Paraguay, and by Doña Saturnina’s earnings from selling chicha and dry goods from their home.

Owing to the cost of the children’s education, Doña Saturnina’s family lived in a home whose symbols of status and comfort were only at the median for houses in Choro. In 2009, it had cement floors, excepting a dirt-floored kitchen that housed a small fridge. They had only recently replaced a small color television bought in 1995, whose channel dial had fallen off and could only be changed with a wrench. On the rough floorboards of the upstairs bedroom, shared by Doña Saturnina, her grandson, and Amanda, stood several varnished wooden wardrobes and a glass case that held a few decorative dishes and mementos from travels to the Bolivian capital, La Paz. They often lamented that their house lacked the flush toilet and shower owned by several more prosperous families in Choro. They had paved their interior courtyard with cement and built several new rooms during the previous few years. Rebar poked out of the roof of their new second story, some of their cement floors were crumbling, and the privy behind their house remained half-dug. In the context of their locality of Choro, their perpetually under-construction house gave off an air of modest prosperity.

The relationships between Doña Saturnina’s immediate family and her two daughters-in-law, the wives of Edgar and David, illustrated the family’s shifting articulation of their social position between social dominance and social inferiority. These relationships were characterized by both the hopefulness and social anxiety that afflicts middle classes in many places in the world. Of all Doña Saturnina’s children, Edgar, the eldest, expressed most explicitly a sense of uncertainty about his social standing. Most people in Choro, including Edgar himself, considered him to have been the first person from Choro to get a university degree. He had lived at home since finishing his law school degree at the public university in Cochabamba in 1995, except for one lucrative year practicing law in Ivigarzama, a boomtown in the Chapare. When the massive Drug Enforcement Administration–sponsored crackdown on coca growing and cocaine production in 1998 ended the boom in the Chapare and sparked a national recession, Edgar moved his operations to the provincial town of Sacaba, a short bus ride from Choro. He rented a tiny one-room office and opened his law practice. Since then, he earned a living but felt his income to be precarious.

Edgar often alternated between asserting an urban, professional identity and a rural, campesino identity. In keeping with his professional aspirations, he told me several times over the years that he was seriously considering moving to the city of Cochabamba. Edgar often bitterly denounced “backward” Bolivia and Choro and extolled the “advanced” nations such as the United States; he said that he could not wait to escape Bolivia. This was why his sisters called him by the nickname “Yanqui” (Yankee), an affectionate reappropriation of the term that among coca growers’ union or indigenous movement activists typically served as a harsh denunciation of U.S. intervention in Bolivia.

Despite these vocal longings to be a prosperous professional, Edgar signaled in other ways that he also remained drawn to a campesino identity. When he came home to Choro from his Sacaba office every evening, he immediately changed from the oxfords worn by urban professionals into red vinyl sandals in the rural style of many of his local friends who had not finished high school. On the weekends, he often went drinking with these friends; he socialized often with rural folk. He continued to live at his mothers’ house rent-free and ate his sisters’ and mother’s cooking. While this was certainly a way to save effort and expense, Edgar sometimes said that he relished the relative quiet and the clean air of Choro as compared to the bustle and pollution of the town of Sacaba or the city of Cochabamba. Edgar also told me wonderingly how he still remembered feeling like a “freak” (un bicho raro), out of his element, when he had begun attending the public university in Cochabamba during the late 1970s. At that time, he had been one of the only students from a rural background. Edgar appeared often bemused, as if he felt that his life embodied an unshakeable paradox. In 2009, he suggested for the first time in my hearing that he might remain living in the countryside for the rest of his life after all, because it was calmer (mas tranquilo) than urban living.

By day, Edgar sat at his desk in his small rented office several blocks from the Sacaba central plaza. He shared the office with his sister Amanda, who had obtained her law degree several years after him. Their clients, many of whom discussed their cases with Edgar in Quechua, appeared to feel more comfortable in this environment—with its cracked and stained walls, shabby chairs, manual typewriter, and piles of worn manila files—than in nearby law offices whose proprietors attempted to lure clients with computers and shelves of shiny legal tomes. During slack periods between clients, the lawyers played cards with Sacaba neighbors at Amanda’s desk. Both Amanda and Edgar complained that they earned much less than they had during the coca boom, despite having many clients, because few people could pay high legal fees without their boom-time earnings.

In part because of his reduced income, Edgar expressed ambivalence about having become a professional. It was only once he began practicing law full-time, he told me, that he realized that he had missed his true calling—to become an accordionist specializing in regional Cochabamba music. Edgar began traveling long hours on his days off to take lessons from elderly accordion masters living in provincial towns throughout the Cochabamba valleys, whose scratchy recordings he and his brothers and sisters played during parties and when they sold their mother’s chicha. Most evenings, the strains of Edgar’s accordion practice could be heard wafting from his bedroom on the second floor of his mother’s house. While the earnings and social status of a successful accordionist’s life could be a step up from those of his parents, only the most successful musician could hope to rival a lawyer’s prestige and earnings and Edgar never, in fact, left his law practice.

Edgar’s longing for an urban life and higher status showed marked similarities to members of other striving Third World middle classes, to their ethic of rising socially and their longing to take part in transnational modernity (e.g., Liechty 2002; Dickey 2000). Yet Edgar’s pleasure in the “calm” (tranquilidad) of rural life, in going out drinking in Choro chicha taverns with less-well-educated friends, in wearing old clothes and cheap sandals, in listening to provincial music, and in living in his hometown rather than renting an apartment in Sacaba or Cochabamba, also marked him as ambivalent about which lifestyle to pursue and which class and race to identify with.

Edgar’s anxiety about upward mobility, his apparent conflict between wanting to join the professional middle class and simultaneous comfort in lifeways defined locally as those of campesinos and Indians also emerged in his relationship with his common-law wife, Doña Cinda.2 Doña Cinda was a cholita like Doña Saturnina: she wore her hair in two braids and wore a pollera.3 Doña Cinda worked as a part-time housekeeper for a wealthy local family and also washed clothing for prosperous families in the town of Sacaba. She and Edgar began their relationship in 1995 and had two children together. Most Sundays, if he was not drinking chicha with friends, Edgar spent his time with Doña Cinda, who lived about a mile down the highway from Edgar’s mother’s house.

By 2006, Edgar’s sisters and mother had been nagging Edgar for years to baptize his daughter, Claudia, who was then six years old. Most parents with rural origins baptized and named their children on their first birthdays; urban middle-class parents usually baptized their children as tiny infants.4 Like the rest of his family, I took Edgar’s failure to baptize Claudia as a symptom of cruel disregard for his children and their mother. In 1998, he had taken his eldest son, Teo, away from Doña Cinda’s care to Doña Saturnina’s home, claiming that Cinda was irresponsible. His mother and sisters took primary responsibility for raising Teo. Edgar had often explained to me that Cinda was “not my real wife” and that his children with her—including Teo, with whom he lived—were “not my real children.” He often said, half defiantly and half longingly, that he expected to find another woman who was not de pollera at some unspecified future date, one who would be more suitable to his station as a profesional. Edgar was echoing the notion that professional-class men should have liaisons with cholas but not marry them, a widespread maxim among elite Bolivians for several centuries (see Albro 2000).

Such cruel statements about Doña Cinda and his children seemed to express Edgar’s sense of uncertainty about his social standing; they also sometimes angered his sisters and mother. On Christmas Eve in 1998, as we sat in a state of semi-stupor after our enormous holiday meal, Edgar expressed misgivings about having recently brought his son to Doña Saturnina’s house. He exclaimed in a tone of mild irritation that he did not want Teo to hang around him because Teo would likely speak to him in Quechua in front of Edgar’s friends (presumably lawyers). His sister Deysi harrumphed and burst out to me in private a short while later, “It looks like he doesn’t care about his son! If I had a child, I would be working only for him.” His sisters Amanda and Deysi often rolled their eyes and grumbled angrily at what they saw as Edgar’s neglect of his family. He sent only Teo to Sacaba schools in the urban provincial school district. His other child, Claudia, attended the Choro elementary school in the rural, and inferior, school district. In exasperation, the sisters urged Edgar to either marry Doña Cinda or leave her definitively.

But they did not like her either. Amanda and Deysi often lampooned Cinda’s heavily Quechua-accented Spanish in falsetto voices, echoing racist television comedy shows from the 1990s in which middle-class male actors cross-dressed as cholas. The sisters laughed gleefully when Teo insulted his mother. Once, for example, when Teo was nine years old and had not lived with Doña Cinda for six years, they laughed encouragingly when Teo exclaimed scathingly, allying himself with them and against her, that he would never return to live with “that washerwoman” (esa lavandera). Sometimes they protested to me that, while they sympathized with Teo’s mother when Edgar insulted her as a cholita, Doña Cinda showed poor moral character and was not worthy of their respect. “She’s nuts [loquita]! She says bad things about us to other people,” Edgar’s sisters told me, seemingly in an attempt to justify their mockery.5

Deysi, Amanda, and Doña Saturnina explained that Doña Cinda had begun a campaign of malicious gossip about them after Doña Saturnina had visited Cinda one day to warn her that Edgar might never marry her. Doña Saturnina, in their telling, hoped Cinda would leave Edgar because he neglected her and their children. Cinda was young—nearly ten years younger than Edgar—and fair-skinned and pretty; she could find a better husband. But Cinda, instead of being grateful, blew up at her, raging that Doña Saturnina’s true concern was that Cinda was not a profesional like Edgar. She threw Doña Saturnina out of her rented house.

When telling me this story several years later, Doña Saturnina sighed and said in a resigned tone about Doña Cinda, “She is dying to marry him [Pay wañurisan casarinanta].” Cinda held on to Edgar because he was a lawyer, even as she was furious that he contributed only minimally toward her and her children’s expenses and spent very little time with them. Deysi chimed in with irritation that Doña Cinda often bragged to others in Choro, “My husband is a lawyer,” implying that this bragging was uncouth and demonstrated Cinda’s lower status. When I asked why Edgar did not finally marry her, given that so many years had passed during which he had never carried through with his threat to marry a professional, Deysi replied with a weak smile, as if discomfited at expressing snobbishness explicitly: “It’s that it’s not so acceptable [no es tan aceptable] for a profesional to be married to a cholita.” She continued that if the cholita were someone decente (morally upright) perhaps it could be done. But Doña Cinda was not decente: she was a gossip and had a child from a previous relationship. With this comment Deysi demonstrated how middle classes often assert distinction using a rigid morality, in addition to dress, wealth, language (a Quechua accent), and education (see Liechty 2002; de la Cadena 2000; Gotkowitz 2003). Deysi implied that Cinda’s moral failings as a gossip and promiscuous woman confirmed her rightful place in a lower class and racial category. By implication, in the relational logic of class and race in Bolivia, all of Edgar’s family raised themselves socially by criticizing Doña Cinda for being immoral and a cholita. And yet it seemed, if Doña Cinda was bound to Edgar, despite her anger, through her longing to associate with a professional and through her economic dependence on him, Edgar was also bound to her in ways that he could not bring himself to admit directly: his discomfort with fully adopting an urban lifestyle and professional status.

The occasion of Edgar’s daughter’s baptism brought to the surface Edgar’s conflicting hopes and anxieties about his middle-class status and brought to a head Doña Cinda’s unfulfilled aspirations for upward mobility through her relationship with Edgar. Both Edgar and Doña Cinda appeared to want earnestly to baptize Claudia but also appeared unsure about whether or not they wanted anyone to attend the event and the party afterward—usually an opportunity for joyful drinking and dancing with the parents’ friends and relatives. For example, while Edgar and I planned the logistics together, Edgar shied away from my suggestion that he have his daughter baptized in the large, ornate provincial church in Sacaba. All the other Choro families I knew, wealthy and poor alike, had baptized their children there. Instead, Edgar insisted on the rural church in the nearby village of Muyu. When I asked why, since the Sacaba church was only a few blocks from his office, he admitted sheepishly, “Because my friends are pains in the ass [fregados].”6 He explained that if they found out about the baptism, they could reproach him with the question, ‘Why did you wait so long [to baptize her]?’ His long delay would be taken as evidence that he lacked proper fatherly concern for his children. But, he added, he also worried they might tease him by saying, ‘It turned out that his wife is a cholita!’ His wife’s status, when publicized among other professionals, could unmask him as other than the upwardly mobile persona that he hoped to convey.

And so, the Saturday afternoon of Edgar’s daughter’s baptism found only four of us winding up the highway between Choro and the Muyu church in Edgar’s purple Mitsubishi, a car he had bought used to try to enter Cochabamba’s auto resale market as a sideline to his law practice. Edgar sat up front with his best friend, a cousin who hadn’t completed high school. I brought up the rear with my teenaged goddaughter, whom I had roped in to keep me company. The churchyard was deserted when we arrived, apart from Doña Cinda and six-year-old Claudia sitting huddled together against the wind and harsh afternoon sunshine on the church’s yellowed front lawn. Claudia seemed shyly pleased at the pale green dress I had bought her and gamely tried to wear the black patent-leather shoes that were clearly too big (I had never met her).

Only one other child was being baptized that day; in the Sacaba church on Sundays, by contrast, hundreds of babies routinely were baptized together. Claudia, my new goddaughter, was so much older than most baptized children that the priest-in-training who officiated did not realize that she was to be baptized and excluded her from the beginning of the ceremony until we called out urgently to him from a rear pew.

After the baptism, we returned to Doña Cinda’s rented house in Choro. We sat at a battered Formica table and ate chicken she had baked that morning. The wind blew bits of trash across the grey dirt courtyard and rattled the window shutters and doors. It was a desolate scene. Edgar and his friend quickly escaped to a party down the road and my teenaged goddaughter to a youth group meeting, leaving Cinda, Claudia, and me. Cinda looked sober. Trying to cheer her up, I invited her to my going-away party, which would be held in a few days at Edgar’s parents’ house. Cinda burst out that she would never enter Doña Saturnina’s house and began to sob. “They are all students!” she cried vehemently in Quechua. “I am not a student.” She told me about a recent fight in which Amanda, Edgar’s sister, had insulted Doña Cinda. “Kiss my ass [sik’iyta muchaway],” Amanda had told her in Quechua while accusing her of being unworthy of Edgar.

Claudia’s baptism revealed that Doña Cinda’s and Edgar’s shared ambitions for middle-class status were, in fact, incompatible. Doña Cinda hoped that marrying Edgar, a lawyer, would raise her social and economic standing. Edgar, however, worried that acknowledging Doña Cinda, a cholita, as his wife—rather than his mistress—would lower his standing. He had not come so far up in the world that he could afford to have a cholita wife. But he also worried that his lack of commitment to her and to their children, when made public, would threaten his moral reputation as a responsible—and middle-class—father and husband.

The contrast between Edgar and David illustrated their intermediate class and racial identities and their classically middle-class anxieties and aspirations. David was acknowledged as the most ambitious and the most successful of the family. Widely regarded as handsome and an enthusiastic dancer at parties, he told me that he had decided to become a pediatrician after seeing seven of his siblings die as infants from easily treatable diseases. He had graduated with excellent grades from a well-regarded public medical school, amassing prestigious scholarships. After several years working as a pediatrician in a large hospital in Sacaba Province, in 2008 he was named hospital director in a Cochabamba clinic, a distinct honor. He also ran a thriving part-time private practice on the outskirts of Cochabamba City. I sat in on several of his medical consultations with Choro children, during which he treated them and their parents with more respect than did urban-based doctors who were often cavalier or downright disrespectful toward their Quechua-speaking patients.

When David talked to me about his own social and economic mobility, he expressed an excitement and confidence that contrasted sharply with Edgar’s ambivalence and puzzlement. David seemed to feel that his economic and social plans for upward mobility were coming to fruition. While Edgar characterized himself as feeling out of his element during his entire time as university student, David told me he had quickly outgrown such sentiments. David talked with obvious pride about his close friends who were prominent Cochabamba doctors, his decision to send his son and daughter to private schools in Cochabamba, and his plans to tour Mexico and the United States with his wife and children. Part of his confidence may have stemmed from his more secure job. He had obtained a tenured physicians’ post in the public health system, while Amanda and Edgar, as lawyers in private practice, were subject to the vagaries of supply and demand for their legal services. It seemed to me, however, that David’s confidence also emerged from his own temperament and from the ways in which in-between, middling status could lead people down different potential life paths.

The relationship between Doña Saturnina’s family and David’s wife, Eliana, a nurse, contrasts directly with their relationship with Doña Cinda and shows the ways in which the family members were equally anxious and torn between ethics of hierarchy and egalitarianism when they perceived themselves to be playing the lower-status role in a social relationship. As soon as David began dating Eliana, conflicts arose between Eliana and Amanda and Deysi. The sisters claimed that Eliana acted socially superior to them. This outrage contrasted with the sentiment of superiority they expressed in regard to Edgar’s wife, Doña Cinda. It seemed that while they saw Doña Cinda as a drag on the family’s prestige because she was socially inferior, their sister-in-law Eliana was a drag on the family’s standing because she belittled them, albeit subtly.

I had assumed at first that Eliana would be popular with David’s sisters because she seemed to share so many of their amusements and their family history. Like them, Eliana was gregarious, laughed easily, loved dancing to Cochabamba valley accordion music, and happily passed her weekend afternoons chatting with friends while they treated each other to round after round of chicha. Eliana’s parents shared Doña Saturnina’s and her husband’s background: they were from another Cochabamba valley provincial town, had weathered faces that attested to lifetimes of agricultural work out of doors, and her mother, like Doña Saturnina, wore a pollera. Both sets of parents appeared equally rigid and uncomfortable in their lace-up shoes and constricting finery in David and Eliana’s wedding photos. Where Doña Saturnina and her husband had sent their children to college with the proceeds of their coca plots, Eliana’s parents had sent Eliana to nursing school with the proceeds of their several dozen hectares of soy and cotton in the eastern tropics.

While Amanda and Deysi eventually warmed up to Eliana more than they did to Cinda, they often muttered exasperatedly at her snobbery. Eliana was altanera and creída (stuck-up), they complained. First of all, they explained, she refused to spend extended periods of time in their family home in Choro. Whereas David nearly always visited home on the weekends and continued to sleep over many Saturday nights in his old bedroom, Eliana almost always went back to her and David’s house in Sacaba to sleep. Eliana confessed to me that she felt stifled sleeping in David’s small room that stood next to the family latrine. The sisters mimicked Eliana almost as savagely as they did Doña Cinda, exclaiming in Spanish in falsetto voices while pointing to different places in their home, “This is dirty! That’s dirty!” With this parody of Eliana, they echoed the widespread concerns of rural residents, inherited from the structural subordination of rural indigenous communities under colonialism, that rural homes, and the countryside as a social and moral space, were irredeemably dirty (Gotkowitz 2003; de la Cadena 2000; Weismantel 2001; Larson 2005). This concern, which they and many other Choreños voiced to me at other times, expressed the fear that the countryside (campo) was inherently uncivilized and unbefitting to their professional, middle-class aspirations.

The baptism of Eliana and David’s daughter Magaly contrasted cruelly with that of Doña Cinda and Edgar’s daughter and illustrated the differences within the emergent middle class. Magaly’s baptism, like David’s marriage to Eliana, also sparked discomfort among David’s siblings when they confronted people who were indisputably of higher racial and class status than themselves. Following the baptism of one-year-old Magaly in the Sacaba provincial church, her godmother, a fair-skinned rheumatologist friend of David from Cochabamba city, drove us in her SUV to a local restaurant. We enjoyed a series of provincial luxuries: we ate roast duck, talked, and danced around a long table in a private room that David had rented, gazing out at a slightly scruffy courtyard rose garden. Throughout the afternoon, friends of David from Cochabamba, mostly specialist physicians and their families, arrived and left the party in a never-ending stream. With their Spanish unaccented by Quechua, their light skin and hair, and their expensive-looking clothes, they displayed signs of class and racial distinction above that of even David and Eliana. The arrival of a family in which parents and their two children shared startlingly pale skin, green eyes, and red hair—all rarities in Bolivia—evoked curious whispers from David’s siblings. They asked themselves if they were foreigners or simply very elite Bolivians.

The party following the baptism abounded with signs of class and racial discomfort. Eliana’s friends from nursing school, children born to campesinos like her and professionals of a lower rank than physicians, sat at the middle of the table. They joked with each more quietly than did the specialist physicians from the city, who sat at the end of the table, and few conversations arose between the two groups. The nurses’ skin was, on the whole, darker; the women’s long hairstyles matched those of Eliana, Amanda, and Deysi and attested to a more working-class aesthetic. At the far end of the table, conversing exclusively with the nurses, sat David’s sisters, Edgar, his parents, myself, and Edgar’s eldest son, Teo.

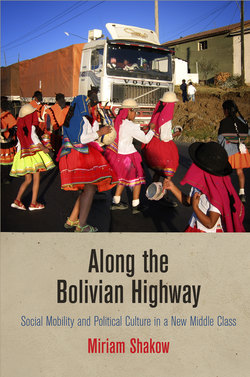

Figure 3. Magaly’s best friend’s sixth birthday in Choro, 2009, with a cake from Dumbo’s, one of Cochabamba City’s most expensive bakeries. Photo by the author.

David’s sister Julia, who had dropped out of high school and wore a pollera, told me surreptitiously during the party that she felt uncomfortable with David’s “high society” (alta sociedad) friends. Even Deysi, the math teacher, though she had lived in Cochabamba for several years and had attended an elite, private college, also said she was uncomfortable. She complained while we took a break outside the restaurant that, unlike at a party in Choro where you could relax and have fun, here you had to act “refined” (refinada). David’s green-eyed friend with her green-eyed children, the one who looked like a gringa, had seemed a particular snob (altanera), Deysi told me, though she had not actually spoken to her. It seemed to me that part of Deysi’s discomfort arose from this challenge to her sense of being on top of her social world as a professional, a privilege she enjoyed more securely within the social space of Choro.

In sum, the relationships between Doña Saturnina’s children and their intimate friends and family illustrated many of the aspirations and anxieties of Sacaba Municipality’s new middle classes, many of whom built their dreams for a new life on the coca and cocaine booms. They professed fierce ambitions for upward mobility, as well as warring ethics of superiority and egalitarianism. They identified themselves along racial and class binaries—sometimes as campesinos and sometimes as profesionales—with few words available to describe being in the middle. And most keenly, they expressed anxiety about this ambiguous social position.

The Axes of Inequality in Sacaba

Alternation between different poles of identity warrants closer attention to both the language and scale of idioms of inequality. Class and race, in the Cochabamba region and other postcolonial societies, as described in Chapter 1, have historically been intertwined concepts. Furthermore, people experience social status through a series of binary oppositions of race and class terms (Weismantel 2001). Some of these terms emerged from Spanish colonialism while other terms are of newer origin. These terms raise distinctions based on wealth, as in pobre (poor) versus rico (rich); race, as in indio versus mestizo; and geography, such as rural or urban (Table 1).

Table 1. Common binary terms of unequal race/class in Sacaba.

| Subaltern | Elite | Formal Bases of Distinction |

| indio—Indian lari, salvaje—savage | blanco—white q’ara—White urbanite | Race |

| pobre—poor clase popular—popular class humilde—humble waqcha—poor and alone | rico, ricachón, de dinero—rich | Wealth |

| campesino, agricultor—peasant | rico, ricachón, de dinero—rich; profesional—professional, college educated | Occupation, peasant geography (rural/urban), and wealth |

| indígena—indigenous originario—native | blanco—white | Race-culture (positive evaluation of indigeneity) |

| analfabeto—illiterate no ha estudiado—didn’t study | bachiller, professional, college educated | Education |

| chola—wears a pollera and hair in braids | chota—not a chola | Race, class, and education |

| rural | urbano—urban citadino—city dweller | Geography |

| no chapareño—Someone who hasn’t earned wealth from the Chapare | chapareño—earned wealth from the Chapare | Wealth |

Source: Author’s fieldwork

The assigning of elite or subaltern categories depended on who was involved in a particular interaction. Deysi clearly considered herself a professional in relation to Doña Cinda but appeared to feel less of a professional when confronted with David’s pale, wealthy physician friends from the city of Cochabamba. Doña Cinda herself at times asserted social superiority when speaking of even poorer people.

These binary oppositions were shaped by the particular scale of a given place. Within the rural locality of Choro, Deysi vied for elite status with wealthier but less highly educated people but could assert middle-class distinction over poorer people. When she circulated in the provincial space of Sacaba, she was potentially subject to social demotion, as more highly educated or wealthier people who held stronger associations to urban institutions and social networks could outrank her and inspire her to declare herself a campesina. When she moved in social circles based in the city of Cochabamba, as at David and Eliana’s daughter’s baptism party, this potential demotion was more pronounced.

While these middling identities were relational—subject to the status of the person with whom an individual was interacting—some important patterns of identification and status were apparent in the social worlds of the community of Choro, the municipality of Sacaba, the city of Cochabamba, and the nation of Bolivia. Within the social space of Choro, I observed local residents define four general categories of people: very poor; professionals or university students like David and Amanda; prosperous merchants such as truckers, business owners, and farmers; and cocaine traffickers (small scale compared to internationally infamous traffickers but wealthier than all others in Choro). On the scale of Sacaba Municipality, two additional class and racial categories emerged in conversations among local residents: urban-based professionals, who lived primarily in the densely populated corridor along the highway between Sacaba and the city of Cochabamba; and provincial elite families whose members had been known as vecinos (townspeople, literally “neighbors”) since colonial times. Their families had been medium-to large-scale landowners, professionals, or wealthy merchants before Bolivia’s 1953 Agrarian Reform. They identified themselves as emphatically not campesino and not Indian, though their physical appearance and wealth were not always distinguishable from that of rural residents. When the social environment widened to include the city of Cochabamba, as at David’s daughter’s baptism, people of greater wealth, lighter skin, and elite transnational connections entered: people who had obtained master’s and Ph.D. degrees from Spanish, U.S., Mexican, or Argentine universities or who identified themselves as belonging to the small European-descended population in Bolivia.

If many Sacabans used alternating binary opposites as terms of identity, some people seemed to wrestle actively with the question of whether or not rurality and urbanity represented sharply separated, unequal worlds and identities. The vision of rurality connoting poverty, cultural otherness, and backwardness is exceedingly common in postcolonial places like Bolivia (e.g., Pigg 1992; de la Cadena 2000; Kearney 1996; Subramanian 2009).

Certainly, there were differences in access to amenities between officially rural Choro and officially urban Sacaba Town. I ran out of Doña Saturnina’s house one afternoon in 2004 to try to find a head of garlic and a packet of mayonnaise—common items in corner stores in the provincial town of Sacaba—to cook dinner. Of the four tiny stores located in private homes in Doña Saturnina’s sector of Choro, all were either closed or sold out of both items. When I arrived home empty handed, Celia, the twenty-two-year-old architecture student and the baby of the family, greeted me with a scowl. “This is the furthest corner of the world [el último rincón del mundo],” she exclaimed in mock despair, as she lolled in front of the television on her mother’s bed, amid the blare of highway traffic. “I’m sure that where you live, there are lots of supermarkets—there are hypermarkets [hipermercados],” she said, surely thinking of IC Norte, a chain of enormous grocery stores in Cochabamba City. Such complaints presented Choro as a rural space walled off from and inferior to urban ones, despite its many amenities that distinguished it from more remote hamlets.

Yet this notion of rural and urban as separate vied with everyday evidence of movement and fluidity: the long history of relational identities and geographic mobility; the economic ties between farmers, merchants, and urban consumers through regional markets; more recent waves of migration since the 1970s coca boom; and the administrative linking of rural to urban areas within the same municipalities through the Law of Popular Participation in the 1990s. The actual state of infrastructure and services in much of Sacaba Municipality was better than in many officially designated rural areas of Bolivia. The construction of a major highway in the 1960s had permitted widespread electrification and running water for all but the poorest Choro households by the 1990s. Public transportation from Choro to Sacaba and Cochabamba was available during the day to anyone who could afford bus fare.

The most perplexing issue for Doña Saturnina’s family, however, was not the paucity of services in Choro. They spent most days in Sacaba or Cochabamba and, like other prosperous families in Choro, could purchase mayonnaise there and could, more significantly, afford to pay for urban doctors and schooling. Rather, their urgent questions centered on the extent to which they and others identified them with the countryside. Sacabans often divided the possession of middle-class distinction—described in Spanish by the adjective culto (cultured) and the nouns criterio (discernment) and civilización (civilization)—along rigidly separate rural and urban lines.

A variant of this local conceptual model posited the qualities of middle-class distinction as ebbing in concentric circles along a gradient from urban to rural areas. A bus driver and urban neighborhood leader whose parents had been Sacaba provincial elites, Don Álvaro, explained to me earnestly that Choro residents rarely left Choro and Sacaba Town residents rarely left the provincial town center. While giving me a ride one day between Sacaba Town and Choro in 2005, he affirmed that people in the town of Sacaba had more “criterio” than those in Choro. Pointing through the car window to mechanics’ garages, half-built restaurants, and cornfields that sprawled along the highway, he argued that the criterio of the inhabitants of each locality decreased gradually the closer one got to Choro. He struggled to define criterio, explaining that, whatever it was, criterio existed in a person as a function of the amount of time he or she had spent in the town of Sacaba or the city of Cochabamba. Criterio thus seemed to mean a classed and raced form of good taste, akin to Bourdieu’s use of the term “distinction” to depict middle-class notions of propriety, discrimination, morality, and intelligence (Bourdieu 1984). Don Álvaro’s depiction of people residing in officially designated rural areas as motionless, as stuck in place, was so striking because it was readily contradicted by the couples we passed at that very moment waiting by the side of the highway for rides to the tropics, bundles of clothing at their feet, and by the stream of minibuses that zoomed past us in both directions and which Don Alvaro himself had driven for many years. Sacaba, like the region of Egypt studied by Amitav Ghosh, “possessed all of the busy restlessness of an airport’s transit lounge” (Ghosh 1994:173). Don Álvaro’s notion of a clean rural-urban gradient of identity, however crude and ill matched to the reality, was still more nuanced than the binary divisions between rural and urban identities used by many other Sacabans.

Race and class intertwined with geography, furthermore, in the binary hierarchies of power. Racial insults persisted despite the revolutionary government’s declaration in 1952 that indios would be identified henceforth as campesinos and that all Bolivians would henceforth term themselves as socially equal, mixed-race mestizos rather than as subordinate indios or superior whites (blancos). Racial meanings that slipped into explicitly class-based terms like campesino were also woven into geographic terms like rural, countryside, urban, and city (Klein 2003; see also de la Cadena 2000; Weismantel 2001).

Bolivian public and private talk also remained liberally peppered with explicitly racist epithets in 2006. Some regions of Bolivia experienced more severe racial polarization, for example, in eastern Bolivian regions such as Santa Cruz. Choreños who had traveled or settled there sometimes reported that easterners sometimes called them “Indians” or “shitty highland Indians [kollas de mierda]” (see Fabricant 2012; Postero 2007). According to reports I heard from several people from various regions of the country in 2009, such insults increased immediately following the election of Evo Morales in 2005, as eastern elites saw their social and economic supremacy challenged (see also Schultz 2008).7 Many Sacabans, in turn, referred to western highland residents as laris, a term that combined the racism of the Spanish epithet indio with the rural connotations of the English class term hick. Lari signified uncivilized backwardness and moral inferiority. “If you sit down with [laris] they won’t share even a morsel of food with you!” exclaimed Bald César, a sawmill owner residing in Choro. “They are not civilized people, they are savages!” similarly exclaimed Don Felipe, a man whom neighbors at times insulted behind his back as a lari himself, because he was poor and was widely criticized as having too many children. A desperately poor teenager, whose home lacked electricity and running water, explained why her father refused to live with her and her mother in Choro. A neighbor in Choro “called my dad a lari and that’s why he doesn’t come. As if he’s a lari! Her son-in-law, well, he’s a little lari [larisito] himself!” Amanda, in a moment of frustration with the elected leaders of Choro’s community council, exclaimed that they were “laris” because “they are very disorganized!” Disorganization, imprudence (“too many” children), poverty, lack of generosity, as well as highland origins could thus elicit racist epithets of Indianness.

In Sacaba, racist insults between intimates hurled in moments of anger were often couched in irony or joking, though they appeared to sting their targets deeply nevertheless. One day, for example, a married couple was having an argument while drinking with friends in a Choro chichería. The wife spat “Lari!” at her husband and explained to me with a tense smile that she only insulted him with that term when he went on a drinking binge. He emphasized to me, by contrast, his face also rigid and tight lipped, that she insulted him in this way because he hailed from a highland town. His grim expression attested that he felt this racial insult from his wife sharply. As with Edgar, who explained that he was justified in treating Doña Cinda with disregard because she was a chola, racist insults between intimates appeared to be deeply wounding.

Racialized teasing was also very common. For example, Deysi and Amanda were extremely fond of Edgar’s son, Teo, whom they had help raise, but did not spare him their sharp tongues or biting humor. Since he had come to live with them at age three, his aunts often mockingly shouted the same epithets at him that they used on their brothers when they did something that annoyed them: “Negro, indio, feo [Black, Indian, ugly]!” Although they always assured me that they were joking, Teo repeated these outbursts in other contexts, making the racism of these insults more explicit. For example, once when he was eight, while watching Sábado gigante, a Saturday-night TV variety show broadcast from Miami throughout Latin America, Teo gazed raptly at the bikini-clad, high-heeled hostesses who often performed dance routines. As one Afro-Latina hostess entered the screen, Teo screamed, “Negra, fea!” I was shocked at this harsh expression of prejudice, particularly since virulent racist epithets in Bolivia were usually targeted at Indians, rather than at Afro-Bolivians, who comprise about 1 percent of the population. Afro-Bolivians were usually the targets, instead, of an objectifying, paternalistic exoticism. The entire family, including Teo, adored Doña Saturnina’s Afro-Bolivian godson and often remarked with wonder, rather than scorn, at the contrast between his green eyes and skin darker than theirs. It seemed that Teo had picked up on the barbed quality of his aunts’ banter but not yet learned to direct it precisely nor to cloak it in the guise of humor.

Even the kindest people participated in such racialized banter and expressed the finely tuned color-consciousness of Bolivian society, couching their remarks in irony or joking. A few months before becoming ordained as a Catholic priest, a gentle friend of the family named Denis had Doña Saturnina’s children in stitches recounting his recent clever play on words. Their cousin Wilson was known to be very sensitive about the fact that his four-year-old son was dark skinned. “Your son is very choco,” Denis had told Wilson mischievously. Choco was the local colloquial Spanish term for light skinned and blond. When Wilson turned on Denis, furious, insisting that Denis was insulting his child by deliberately saying something that everyone knew was not true, Denis had retorted, “I wasn’t insulting him. He is very choco: he is choco … late!” (a pun on “chocolate” brown). Denis grinned roguishly at us while retelling the exchange and Doña Saturnina’s children roared with laughter. They repeated his joke many times during the subsequent weeks and marveled at his wit.

People also turned racialized disgust on themselves. Amanda, like many other women I knew in Sacaba, often lamented that she was ugly because her skin was “too dark.” Once Amanda, after a long, introspective discussion with her brothers and sisters after we had finished dinner, looked up seriously at me and told me that she had not yet had children (she was then thirty-eight years old and single) because she was afraid of passing on her dark skin to her child. “It was a joke, a joke!” she exclaimed when she saw my horrified expression. She insisted that she was teasing me precisely because she knew how earnestly I always tried to talk her out of such sentiments. Sometimes people extended this internalized racism to their children, like the many strangers on Sacaba buses who lamented to me that their children were “dark and ugly” when they saw my pale, redheaded baby. These were melancholy variants of more lighthearted but still racialized exclamations to me and my blue-eyed son: “Lend me your eyes! [¡Prestáme tus ojos!]” or sometimes, with a flirtatious chuckle, “Lend me your [strawberry blond] husband so I can make a blond baby!” Skin and hair color were common sources of nicknames such as Negrita (Blackie) or Choca (Blondie, light skinned).8

These examples show racialized thinking alive and well in Bolivia, despite the government’s declaration in 1952 that racial consciousness would disappear by fiat. Racial signs, such as skin color and dress, could at times be synonymous with subordinate class signs, while at other times they diverged. Dark skin did not prevent Amanda from becoming a professional, but she appeared to fear that it constrained her options for finding love and forming a family. Meanwhile, Amanda also declared that light-skinned and fair-haired Doña Cinda was socially subordinate in terms in which race and class were indivisible: Cinda’s Quechua-accented Spanish, her pollera and braids, and her purported immoral gossiping and unwed motherhood, demonstrated her lower class and race. That some comments about race were couched in jokes—“black, Indian, ugly!” and “chocolate”—suggests that, like in the United States, Bolivians felt some restraint in making racist comments as a result of government and social movement condemnation of racism. That people often uttered harsh racist epithets in moments of anger at spouses and children also shows how racist speech could channel antagonism and tension; explicit racism marked the momentary lessening of self-control.

By the late 1990s, in response to the national government’s promotion of multiculturalism and the rise of the MAS, some Sacabans had begun to take on explicitly racial terms as badges of pride. “Around here, we are indios, laris,” said a taxi-bus driver in an affirming tone in 1998 as he sped along the road between Choro and Sacaba Town. Yet such self-identification with a term that had racist connotations—rather than the more positive indígena and originario—was rare in Sacaba.

Snobbery and Egalitarianism

The clash between the ethic of upward mobility, which Sacabans often feared was necessarily tied to snobbery, and the norm of equality created personal dilemmas. Deysi, Doña Saturnina’s math-teacher daughter, in her mid-thirties, was an astute analyst of local social relations and a vivid storyteller. On many occasions, she described the social quandaries created by this clash that she began to navigate as she became a professional and attempted to shrug off her status as a “person from the countryside.”

One moment in which Deysi asserted her own middle-class distinction while also condemning snobbery occurred on July 2, 2006, the night of the election for Bolivia’s Constitutional Assembly delegates. Deysi came back to our shared bedroom at her parents’ house with her sometime-friend Norah’s husband. Norah was also a rural teacher, but unlike Deysi, who had a master’s degree from an elite urban university, Norah had earned a combination high school diploma and elementary school teaching certificate (bachiller pedagógico) from a rural boarding school run by Catholic nuns. Norah had been lucky to graduate and find a teaching job in the late 1990s before the Bolivian job market flooded with teachers. Though many people who had earned the less rigorous teaching degree a few years later were at that moment unemployed, Norah had a steady job.

Norah’s husband, Chavo, a successful auto mechanic, was telling Deysi about his long-running arguments with Norah and her mother. He was tearful and his voice was slurred from their recent round of postvote drinking. He, Norah, and their two small children had recently returned to live in Choro from the town of Sacaba in order to keep Norah’s mother company because she was a widow who lived alone. But his mother-in-law constantly claimed that he was taking advantage of her. She insulted Chavo as a bad provider, telling him: “I’m supporting you, here,” and asking pointedly, “And you, what do you have?” “It’s true,” Chavo said defiantly to Deysi. “My father is a poor farmer [pobre agricultor],” while Norah’s mother was a prosperous vegetable merchant who had inherited large plots of farmland from her grandparents. But Chavo’s mother-in-law’s taunts rankled mostly because Norah took her mother’s side, reproaching Chavo for his lack of earning power, saying scornfully, “I’m a teacher! I earn money.” Norah had told Chavo that her salary maintained the two of them and their two small children more than did his income as a mechanic. I was momentarily surprised at the fine distinction that Norah had drawn, since many Bolivians believed that rural teachers, particularly those with Norah’s high school degree, were not true professionals (see Luykx 1999). But Norah asserted her middle-class distinction in her fights with her husband. Chavo had hit Norah in anger, he told Deysi, and he regretted it.9

After Chavo left, Deysi lay on her bed, looking up at the ceiling. She wondered aloud in a thoughtful tone why she seemed to have so much “fear of getting married.” I replied that it did not seem to be such a mystery, given the dire example of Chavo and Norah. I reminded her that she herself had often told me that, as a single woman in her late thirties with a steady, relatively well-paying job, she had quite a bit of freedom—to go to parties with friends and relax on weekends. So many husbands she knew drank heavily, beat their wives, tried to forbid them from leaving the house, or abandoned them to raise their children alone.

I had also noticed, though I refrained from mentioning, that during the years that I had then known them, both Deysi and Amanda had often seemed ambivalent about whom to date. They appeared to continually wonder whether their potential boyfriends were appropriate matches based on their status. It is possible that she, like Edgar, was perplexed about the way in which marriage would constrict her present ability to play with different identities. In 1995, when Deysi was a first-year college student in her early twenties living in Cochabamba, she had confided in me that she would only date men from Choro, never from Cochabamba. This provided a quite small pool of potential boyfriends: though Choro consisted of roughly four hundred families in 2006, few Choreños her age had college degrees.

On election night in 2006, Deysi emphasized the dilemmas created by perceived class differences. She continued, “Around here, it’s mostly this situation: one spouse comes from a family with more wealth and wants to put down [despreciar], to humiliate [humillar] the other one. You know, they say that it’s better for professionals to marry each other and for people from the countryside to marry each other [es mejor casarse entre profesionales o entre gente del campo].” Deysi was thus reaffirming the local hierarchy by which class and racial identity were defined in geographical terms: professionals, among who she counted herself at that moment, were inherently urban, while poor and uneducated people were by definition “people from the countryside.” She repeated that Chavo’s parents were indeed very poor. He shouldn’t have hit Norah, but, on the other hand, Deysi seemed to imply, Norah was engaging in emotional abuse when she touted her class origins as being above Chavo’s. Norah was a snob (altanera), Deysi said, for accusing Chavo of being only a mechanic and not even a high school graduate.

People are, of course, inconsistent. They are the targets of accusations that they also lob at others. On the one hand, Deysi argued that Norah was a snob for belittling her husband because she was a professional and he was not. Deysi had criticized David’s wife and his physician friends on similar grounds of snobbery. She resented Norah as snobbish in relation to herself as well, explaining that Norah was never willing to “share” (compartir): to sit with friends, drinking chicha and chatting. The common term Deysi used to describe such conviviality, compartir, conveys the widespread norm in Sacaba that socializing was an expression of generosity—the opposite of selfishness—as well as a pleasure. On the other hand, Deysi herself had argued that Doña Cinda, Edgar’s wife, was socially inferior to Edgar because of her immoral character in addition to her status as a cholita. Doña Cinda had similarly accused Deysi and her sister and mother of being snobs for not accepting Cinda’s relationship with Edgar.

David on one occasion attempted to insert more nuance into these binary oppositions of rural and urban, campesino and professional. When I asked him in 1998 whether he considered himself a campesino, he replied, “I’m a campesino because I live in the countryside, but I’m not poor like a campesino.” His was a rare assertion that a professional with close ties to both rural and urban areas could potentially assert a rural identity that was also prosperous and professional.

Deysi and Amanda sometimes called themselves campesinas, too, in moments when they pointedly criticized others’ snobbishness and promoted social equality. Their statements, like the examples of overt racism and classism described above, drew on fine local nuances of food, clothes, accent, or birthplace to connote race and class. One day in 2003, for example, Doña Saturnina and most of her children had gathered for a festive lunch while watching the Sacaba municipal anniversary parade from the rooftop of David and Eliana’s apartment building. Amanda handed a plate of fried chicken to David’s seven-year-old son, Alejandro, from a previous relationship. “Me and my mom don’t like to eat chicken skin,” Alejandro said mildly, as he began to peel the skin off his drumstick. “Well,” Amanda replied with mock severity to her nephew, “you and your mother are classy people [gente decente]. We [his aunts and uncles] eat chicken skin because we are campesinos.” Her comment echoed the complaints of Choro parents that their children refused to eat the skin and entrails that Choreños had eaten during leaner times before the coca boom. Similarly, in 2005, David admonished me for not eating the skin of a roasted guinea pig, an Andean delicacy to which I never became accustomed, which he had prepared at his mother’s house. “I am poor [soy pobre]; I eat the skin!” He declared pointedly to me. Both Amanda and David were teaching cultural beginners—a child and a foreigner—to be egalitarian.

If Doña Saturnina’s children expressed irritation when they perceived that I, Eliana their sister-in-law, or David’s city physician friends belittled them, they also complained angrily when nonprofessional and de pollera, but wealthier, neighbors asserted a higher status than them. Such complaints surfaced, for example, when I lamented that a well-to-do, cholita neighbor who owned a trucking business with her husband hadn’t come to my son’s baptism party, which we threw at Doña Saturnina’s house in December, 2005. Amanda remarked in a sharp, ironic tone, “She’s loaded [ricachona]! She only goes to rich peoples’ parties. Because we are poor [pobres], she didn’t come.” Amanda explained that this woman’s discriminatory thinking was “clear from where she goes and how she speaks. For the weddings of rich people [ricachones], she shows up with presents; for poor people, she doesn’t show. These people are creídos [snobs].” Years earlier, in 1998, Amanda, Deysi, and David similarly condemned another wealthy cholita neighbor who owned a successful chicha tavern. The neighbor had reputedly proclaimed that she would reserve expensive bottled beer and cocktails for “rich people [ricos]” at her daughter’s wedding, while serving poor guests only chicha and making them leave early. Amanda, Deysi, and David did not expect the neighbor to treat them as poor and refuse to serve them the expensive drinks; indeed, they partook freely. They nevertheless expressed these episodes as an affront to them personally—they had less visible wealth and cash on hand than their wealthy neighbors—as well as an altruistic concern for the many Choreños who were even poorer. Their protests also illustrate the intense social competition within this middle group in Sacaba, between professionals with little disposable wealth and wealthy merchants and truckers with little formal education. In a manner emblematic of middle classes throughout the Third World, they jockeyed intensely for the social supremacy to be recognized as a middle class, in this case through competing claims of distinctions based on wealth versus education (Liechty 2002; O’Dougherty 2002). Finally, these complaints by David and Amanda also demonstrate how in the social world of Sacaba Municipality, this rivalry for moral superiority could entail, paradoxically, making claims to egalitarianism.

In fact, the sisters termed themselves campesinas and rural and asserted an ethic of egalitarianism in some situations when they were called out as being snobs. In 2003, for example, Deysi recounted a painful episode in which she and Amanda had unexpectedly lost a valued friend. During a party at their home, they had teased their friend, a fellow university student who hailed from a rural town in the Bolivian highlands, that he had no right to criticize them: “Don’t forget that you’re an Apaza!” Apaza is a common indigenous Aymara last name that immediately signals a person’s origins in the rural, Aymara-speaking Bolivian highlands. Deysi and Amanda were subtly marking Bolivia’s racial hierarchy, in which highland Aymara speakers have been viewed as more Indian than, and inferior to, Cochabamba valley Quechua speakers.10 In effect, they had admonished him, in mock severity, not to be an “uppity Indian.” He became angry and told them that they had insulted him with a racial slur, left the party, and never returned to Choro to visit. Thinking back on this event several years later, Deysi said that she and Amanda had spoken in a spirit of fun, but they had been too free with their characteristic, biting humor. “I regret it so much. We were joking around [bromeando], but we shouldn’t have said that…. It must have hurt him to the bone [even though] it was just a slip of the tongue. Surely he went and told his mother what we said to him, and his mother must have said, ‘How could they say such a thing, being campesinas themselves!’” In an assertion of empathy and equality with her friend, Deysi implied that Doña Saturnina could easily have just as easily found herself listening to her own children’s stories of racial and class discrimination. Deysi’s analysis of the joke gone awry seemed to be that she and Amanda had been justifiably reprimanded for asserting racial superiority. Doña Saturnina’s family, in sum, alternated between identifying with superior and inferior racial and class categories and between professing superiority and egalitarianism.

Envy (Envidia)

The common language of envy (envidia, qhawanaku, miramiento)11 in Sacaba marked the clash between the widespread ethic of egalitarianism and the equally widespread ethic of upward mobility. When David, for example, expressed a concern that his old friends and neighbors in Choro resented him as snobbish, he said that they were envious (miramiento) of him. He explained in an interview with me in 1998,

I treat my people well. I speak with them in their language … in Quechua…. In fact, I try to change them, right? I say “You shouldn’t do this…. We need to develop,” … or “Instead of spending your money on this thing, you could do another thing,” always thinking about how they can progress…. I haven’t kept myself apart from them … but people talk, you know? I mean … I’m a serious person, I have a calm demeanor, and people peg me as stuck up [creído]. But it’s they who are separating themselves from me, it’s not because I’m stuck up…. People my age say, “He’s a doctor, so now he won’t say hello to us.” Who knows what they’re saying! So, sometimes when we pass by on opposite sides of the road, they just … say “good morning” and go by, they don’t come up to me…. I think that they feel … I’m not sure … mmm … humbled, ashamed.

David described, with apparent pain, that he was misunderstood as being snobbish; that his intentions were egalitarian but his Choro neighbors and old friends misperceived him as acting socially superior since becoming a professional. In this instance, David did not condemn his former friends’ envy as a moral fault but rather lamented that their ill-will emerged from a misperception of his thoughts and intentions. The implication of their perceived criticism was that David, by believing in his own social superiority, was socially selfish. He suggested that his old schoolmates harbored particular rancor for him, beyond what they might feel toward a snobbish stranger, because they saw him as rejecting them despite belonging to the shared social community of Choro. David countered with the implicit argument that he was not selfish but actually generous, because he tried to contribute to the progress of those old friends by offering them helpful ideas for how to become upwardly mobile themselves. He found, however, that his efforts to present himself as egalitarian had been unsuccessful.