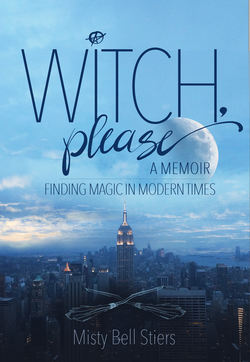

Читать книгу Witch, Please: A Memoir - Misty Bell Stiers - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

How I Became Wiccan

ОглавлениеIt’s not always a tornado and a whole house. Sometimes it’s just a door.

There is no one way to become Wiccan. In fact, there are as many ways to become a witch as there are witches. That’s the beauty of “unorganized religion”: you get to pave your own way and find a path that suits you. There are no hard-and-fast rules, no rewards or punishments for good or bad behavior, there is only this exhortation: Do no harm. This simple phrase is contained within the Wiccan Rede, a main tenet of our belief system. Essentially, the Rede states that one can live as one chooses, as long as it causes no harm to others. You be you, just don’t go interfering with me being me. It’s basically our version of the Golden Rule. (Hey, great minds think alike!)

The story of how I landed here, in my witchy ways, isn’t too complex. It involved no ceremonial candle burning, no spell casting, and no drawing down the moon. Rather, it’s the simple story of how I lost my way and found it again.

It’s the story of a closed door.

As I was getting ready to graduate from high school, amidst all the finals-taking and gown-ordering, I was also rehearsing for a final high school theatrical production with some of my very best friends. (Many, to this day, remain some of my very dear friends.) We were staying late at the theater and probably horsing around a bit too much every night. By that point, we had been inseparable for years: acting in every show together, spending weekends on school activity buses, accompanying one another in various combinations to every school dance. The idea that very soon we would not all be together anymore, despite looming over our heads, was still very abstract. In those weeks, it still felt like we would be together, just like that, always—the way things do when you’re there, in those moments.

One perfectly ordinary night, parents started coming into the middle of our rehearsal, disrupting the usual flow of things. A couple appeared and quietly took their children out of the theater. Everything started to feel wrong, as if it had all gone sideways. I had a feeling like I might be sick; my chest was tight and I couldn’t find my breath. Finally, the director stopped the rehearsal entirely and asked us all to sit down. I remember her asking us to be quiet, and I remember being terrified of the look on her face. She looked . . . broken.

“I have something I need to tell you, and it’s not an easy thing. Marc passed away tonight.”

I’m sure she said more than that, though I don’t remember what. I remember how the words felt, how his name sounded. She cried as she said it. At one point, I think maybe someone else stepped in to tell us more, but if they did, I don’t remember what it was. I just remember hearing Marc had died. I know they told us he had committed suicide, but I can’t for the life of me recall the words they must have tried to use to soften that blow. I can, however, remember in perfect detail how those words hit my heart.

I was in shock. Marc was the boy who teased me over our backyard fence throughout my entire childhood; the friend who taught me how to use a jigsaw during set construction in the theater while we blasted Garth Brooks on the stereo; the person who gave me my first beer, paired perfectly with a graham cracker and a brilliant laugh. Every year at Christmas, Marc would drive a group of us, packed tightly in his car, up and down the streets of our small town on his very own “Tour de Lights.” No matter what we were up to, he always managed to get me home just seconds before my curfew. Marc played a seminal role in my high school experience; we had sung and danced together, built whole worlds together out of plywood and Styrofoam. He had been kind when I needed it most, generous and joyful. None of that aligned with what people were saying to us in that theater. It just didn’t seem possible.

Marc was gone. I couldn’t understand how this had happened, how his heart had somehow irrevocably broken without any of us knowing it was even cracked. Despite the closeness we all thought we shared, he had felt alone. Despite our belief that our days together would last forever, he had chosen not to go on. The reality we had taken for granted came to a screeching halt.

The theater seemed unnaturally quiet. Some of the parents who had heard earlier what had happened stood sentinel behind our chairs. People stood and looked around, knowing they should be doing something, anything, but not knowing what was supposed to come next. I desperately wanted to find the friends I was closest to. I wanted to touch them and look them in the eyes and confirm they were here still—that this wasn’t the world tearing itself completely apart.

I slowly walked up the aisle of the theater, past the urgent talking and crying that had since erupted after the initial moment of stunned silence. I needed to get out. I needed to get to. I don’t recall how I got to Marc’s house that night to sit in his front yard, or who told my parents where I was going, if they even knew. I remember being one of so very many kids camped there, as if our sheer numbers would bring him back, clinging to the people around us while refusing to believe any of it was real. I don’t know what time I went home. I don’t know who drove me.

I spent the next days in the company of those friends: piled up like puppies at night in my living room, stumbling from diner to diner listening to bad Muzak versions of Madonna songs while drinking stale cups of coffee and eating giant bowls of canned chocolate pudding, watching movies in someone’s basement. Talking of everything but. Talking only of, until our eyes were red and our throats burned. We ignored the rest of the world, desperately holding on to one another, making promises, fervently asking if we were okay. We were scared to death that we weren’t okay, in ways we couldn’t see—the ones that truly mattered now, ones we had never even known existed just days before.

We had realized that we no longer had forever. All we had now was each moment before us, these fragile gifts we weren’t entitled to but had been given. It all felt incredibly fleeting and friable, unmistakably not ours to hold anymore.

Eventually, someone insisted we go back to class and finish out the year. We refused stalwartly, until another someone laid down the rule that we couldn’t have an opening night for our play without actually having a school day beforehand. So we went home to our separate beds, our separate rooms, to get ready for our first day back at school.

I remember praying we would all make it through the night.

The next morning dawned as if the world hadn’t broken. I ate my bowl of Cocoa Krispies, grabbed my backpack, and got in my car. But as I was driving up to the entrance of the school’s parking lot, I suddenly just kept going. I couldn’t bring myself to walk through those doors just yet. I couldn’t face whatever was there—or worse, what wasn’t anymore. So I drove to the one place I could think of where I might find peace:

St. Mary’s Queen of the Universe.

It wasn’t a grand church, but it was mine. I had attended mass there three times a week, plus holy days, from the time I was five until I was twelve, and caught every Sunday after. I knew every nook and cranny of that building. There were—are—thirty-three lights on the ceiling. I knew every shape in the stained-glass windows, every crack in the sculpted wooden Stations of the Cross. It was, in many ways, another home to me.

See, I wasn’t just “raised Catholic.” My family would never countenance “potluck Catholicism,” the term applied to those parishioners who only attended mass at Christmas and Easter and who were perceived as picking and choosing what portions of the doctrine suited them. And I had loved my religion. I attended Catholic grade school, and when that was done, I embraced everything I could outside of mass: I attended Confraternity of Christian Doctrine classes on Wednesdays; I helped clean up the bingo parlor every Sunday night (the smell of sour donuts and burned coffee to this day can bring me straight back to that old gymnasium); I counseled at the church’s summer camp; and I was president of our Catholic Youth Organization. I even sat on the state CYO board and helped plan the annual youth conference. I was Catholic.

And so, on that morning when everything seemed upside down, when my heart was broken and my soul shaking, I went to the one place I believed could help me find my way through this terrifying maze of reality, or where, at least, I could find comfort. I prayed. I sat in that soaringly empty church and prayed. I cried all the tears that still somehow remained in me and I begged to feel safe again. And when I was all prayed out, I stood and found my way to the rectory. I thought surely someone there could help me.

It was early, the clock just reaching past seven. Morning mass had yet to begin. Even I, in my foggy, mournful teenage state, knew it was too early to knock on that door—on any door, for that matter. But this place—these people—had always had the answers before, and I was desperate for some now. So I knocked.

Father Emil answered the door in the humor you would expect, though honestly, he was never in what one would call a “good” mood. In my experience, Father Emil wasn’t at his strongest as a priest of the people—at least not to those of us under the age of crotchety. I admit I was a bit intimidated when he was the one to answer the door; he had been with our parish less than a handful of years, and I didn’t know him all that well. In fairness to him, though, he listened patiently as I stood on the stoop pleading my case, asking all the questions he could not answer: the whys and the hows and most especially the what-nexts. It seemed the world insisted on continuing to spin. How was that possible? How could I keep up?

And Father Emil, calmly and quietly, put his hand on my shoulder. “Child,” he said, “there is only one thing left to do: pray for his soul. He has committed a mortal sin.”

And then he closed the door.

If he had said to me in that moment, “I will pray with you, and God will help you through this sadness,” I think my whole life might have been different. I used to wonder: What if he had taken me in to pray? What if he had offered any comfort at all, if he had shown me the compassion I had always associated with my church? When I look back, that moment is such a crossroads, where a small breeze might have been able to blow me back on my familiar course, even if just for a while. Instead, as the door to the rectory clicked into place, something inside me also closed. The world tilted and blurred, and I found myself sitting on the cold cement steps outside, looking with new eyes at what surrounded me.

I envisioned the years I had spent in that place. I remembered the Easter egg hunts on the green, perfectly manicured lawn, in which filling your basket was more a contest in speed than a test of your skill in discovery; the midnight masses on Christmas Eve, when the windows of the church glowed magically in the dark from the candles lit inside; the joy of the acoustic mass, where I sang as loud as I wanted without worrying who could hear my not-so-wonderful voice; the All Saints’ Days when, as young children, my fellow students and I dressed up as saints in all manner of sheets, cardboard wings, and giant paper pope hats to parade across the parking lot between cars from the school to the open doors of the church. One by one, my entire lifetime’s worth of memories so far wrapped themselves up and moved to a distant part of my heart.

Father Emil was right, of course, according to old-school Catholic doctrine. In that moment, however, I realized that Catholicism was no longer my doctrine. The God I believed in, the God I had thought existed, was merciful and kind. He was meant to love unconditionally. How could I possibly kneel to worship at the feet of a God who would turn away someone whose heart was broken? How could He condemn my friend for breaking under the weight of a world God himself created? I reeled under the sudden realization that the answers I had found at St. Mary’s weren’t the ones I had sought.

I understood then that if the world would insist on continuing to spin, I would have to make the decision to live as it did so. And if that were the case, I decided, I would need to find a new path to walk along in the indifferently spinning world. This one would no longer work.

I slowly turned away from the building and I left it all behind.

I spent the next few years gradually letting go of many of the things I had once believed. I went through a type of mourning, bidding good-bye to traditions I admit missing to this day. There is something imminently magical about the ritual of Catholicism, the mystery and ceremony of it. Is there anything more transcendent than midnight mass on Christmas Eve? Even after all the years that have passed, I can still close my eyes and feel what it was like in those wee hours of the morning, carols wafting through the great space of the cathedral: the sensation of something surreal happening, the great anticipation of the dawn and all it could—would—bring, the feeling of standing at the precipice of something beautiful and pure.

I longed to find another path whose rituals would speak to me as those moments had, and I tried to come to terms with the fact that while I held dear the moments I’d spent standing in those places, raising my voice in praise, I no longer truly believed in any of it. I began the painful work of sorting through what I believed because it was what I was taught and what I believed because it felt right. It was a messy process.

Part of that process was a sudden and overwhelming feeling of loneliness. I had lived my life up until then accompanied by an omniscient father figure who constantly watched over me, someone who had a plan for my life in its entirety and who never left me. If He happened to be occupied, I had the Holy Ghost or Jesus himself to turn to. And if They were also busy with other things, I still had a legion of angels and a host of saints to call on. I was brought up to believe I was never truly alone, and so I hadn’t been. In my head and in my heart, I had found comfort in knowing I had my own personal saintly squad. Now, like being unable to clap Tinker Bell back to life, I found that without the faith to power this mighty host, they dropped away. I stood truly alone for the first time.

I wanted to find comfort, to find a place in my world where I would feel less alone, even if that meant having to learn how to be at peace with my own company. I began the difficult process of truly looking inside myself. I needed to know my own heart in order to move forward; I needed to figure out how to live without a legion behind me and to find the power of protection and security I had always sought from those angels and saints within myself. I felt as if I were standing at the bottom of an infinitely tall mountain. Yet slowly, I began my climb, reminding myself that even the great Mississippi River starts, somewhere, as a body of water just steps across. I tried to make at least a temporary peace with my lonely heart.

In doing so, I became annoyingly curious. You know how you’re not supposed to talk religion or politics in civilized company? Oh my lord, I was so uncivil. I asked everyone what they believed and why. Tell me! I couldn’t get enough. I borrowed and bought an endless stream of books. I revisited the Bible; I read parts of the Torah and the Koran. I became acquainted with what seemed like endless numbers of Eastern philosophies.

It didn’t take me long to realize that the spiritual path I had come from and its closest relatives weren’t for me. While I adored the rich myth and allegory of the Abrahamic faiths, their larger organizational structures lost me every time. I had a hard time believing, really believing, that there was something outside of myself in charge. And I couldn’t come to terms with the notion that there was a select group of people who had more right to call on that something than I did. Beyond that, I just couldn’t accept that there was an omnipotent being calling the shots: forgiving with one merciful sweep of the hand, all the while directing a vengeful plague with the other. There was just too much I couldn’t reconcile in these ideas, too much I fought against. But oh—the idea of the importance of the mother’s line, her connection to her children, in Judaism? That sang to me. And did I mention the stories, the amazing tales, that come from all three? I can still listen reverently to the legends of the saints and prophets, the tales of floods and famines and great towers that stretch into the sky.

Alas, it just wasn’t me. I eagerly consumed all of the literature, but I couldn’t make peace with answering to a singular, unknown being for all the wonder in the world, to being relegated to the status of what felt like a mere pawn in a great game. I didn’t want to live a life that would be judged and met with reward or punishment at the end—I had already learned that those doing the judging didn’t always play fair. They didn’t allow for, well, the fragility of humanity. None of it felt true to me, as much as I had hoped it would. Finding peace in any of these places somehow felt like I would be playing it safe, because they were connected to my beginning: they shared the roots, if not the branches. They just weren’t mine anymore.

The Eastern philosophies had their own wonderful myths to share, their own cast of great and magical characters with which to fill my imaginings of the world. I adored the complexity and drama of Hindu and Buddhist lore. These tales were so different from the stories I knew, and yet absolutely familiar. They, in turn, led me to rediscover the classical Greek and Roman myths I had read and studied on my own as a child. I loved revisiting the stories my dad had excitedly shared with me when I was small, on afternoons spent envisioning the heroes and heroines, the gods and the Titans. I had always loved trying to imagine who I would be in these stories, who we were most like, who would triumph in the end.

I became entranced with the overlap of themes and creatures that appeared across all of these great myths. I gathered the stories like so many beautiful puzzle pieces: tales from the Egyptians and Greeks, the Romans, the Norse. I made a game of trying to seek parallels among them all—Aztec to Hindu to Christian to Greek. The commonalities seemed never-ending. In the end, I found they were all more similar than I had previously thought possible.

I also realized something else important. These great books, these tenets of faith, I consumed them like literature. I wasn’t finding my truth there. I wasn’t feeling connected, I was only playing at connecting them. It wasn’t the same.

And so, after reading countless books, attending numerous church services and some truly wacky prayer circles (A church of psychics! Who knew such a thing even existed?! The one I found was in Sarasota, Florida, and I highly recommend a visit, for curiosity’s sake if nothing else; it was frightening and fascinating all at once), I still had found nothing that felt quite right. What I had discovered was that most religions all believed in basically the same thing: Live a good life. Try not to be an asshole.

I was completely down with that, but I wanted more. I wanted to find a spiritual home. I missed the one I’d previously had; I felt unanchored in a way I had a hard time putting words to.

Then one night in my second year of college, as I sat in my friend Karen’s dorm room, she mentioned she had a book she thought I should read. It was yet another book about religion, which she knew was right up my alley. The book was called Drawing Down the Moon, by Margot Adler. My heart skipped a beat at the possibility: something new! Then she explained that the friend who had sent it to her was a practicing Wiccan.

What?

Um, no.

I was looking for a spiritual path—I was not looking for a Goth makeover. I immediately put the book down. She insisted I take it, assuring me it was right up my alley—all about that “what-makes-the-world-spin mumbo jumbo.” She pointed out that at the very least I would discover what paganism was all about; I might as well round out my research. So out of reluctant curiosity and, truthfully, being too lazy to continue finding reasons not to, I caved and brought the book home with me. In the midst of a fit of insomnia weeks later, I cracked it open.

I read it twice.

I was Wiccan—no incantation or ceremony needed.

In the end, finding a spiritual home wasn’t entirely as easy as turning my back on a closed door—it required me to not give up on finding an unlocked window. Eventually I found a path of my own, a line of belief that felt right to me. Wicca was both something I could hold on to and something I could define on my own. It was exactly what I needed. It was me.

I know it’s not right for everyone. Something I’ve held on to all these twenty-plus years since leaving Catholicism is the idea of how wonderful this world is, how amazingly fantastic it is that it provides so many paths to peace, so many traditions to walk in, that we can all find something that fits. I don’t believe in any one universal truth. I believe we all do our best with what we have and what feels right—that whatever great power spins this world also gives to all of us the capacity to find a way to inhabit wonder. There is the possibility of enlightenment and harmony for all to find, if only we wish to find it.

That’s the true magic that exists in this world.

And I should know about magic. I’m a witch.

I can say I’m a witch with confidence now, but it took me years to get here. In theory, becoming Wiccan made perfect sense; the beliefs and system around it spoke to me like nothing else I had previously found. It seemed natural to me to recognize the turning of the year, to call to attention the points of change and pause to recognize them. I felt absolutely at home building traditions around the solstices and equinoxes, recognizing how the darkness of the winter and the brightness of the summer could affect my being, figuring out how to embrace the natural turning of the world and find my place in it. I began to follow the phases of the moon and fell in love with the idea that every month there was a chance to start anew. Always, no matter what else was happening, the cycle of reinvention and reemergence continued. I learned that even the moon took time to disappear and find quiet before it allowed itself to grow as big as it could and shine bright. I started to feel connected to the world around me like I never had before. I began to feel less lonely.

Yet when I went to learn more—wanting to research in order to be sure, to understand, to find answers to the questions that now popped up in my head on a regular basis—it became outrageously intimidating. Suddenly I was right where I had thought I’d end up, where I had feared to be from that first moment when I saw the book in Karen’s dorm room. At Pagan Pride festivals and coven meetings, in small occult stores and workshops, I found myself surrounded by people whose names sounded fetched out of fairy tales, images of black candles and smoky cauldrons, books enticing me to cast spells for love and money and luck. At first glance, I found none of the pillars of belief that had so called to me before. Instead, I found every stereotype I had ever heard or imagined. I felt lost in an itinerant Renaissance faire, surrounded by pixies and people who saw witchcraft as more Eastwick than east rising. I started to doubt where I was and whether this spiritual journey was truly right for me. Still, I couldn’t shake the sense that this was it. I wasn’t willing to give up this place of peace I had found over a few black corsets and spiked jewelry. I thought there had to be more—or rather, less.

It took a few awkward coven meetings and even more awkward conversations before I learned the phrase “solitary practitioner.” Someone I had become friends with (the original source of the book I borrowed from Karen, in fact) eventually shared with me that he wasn’t so into the whole coven thing and the culture of a lot of it and had found his place as a Wiccan who chose to follow the basic tenets without involving himself with a coven—he simply lived life as a witch, in the way he chose to define that. This seemed revolutionary to me. It changed the way I saw myself as Wiccan—it helped me truly see myself as Wiccan.

With this new perspective, something began to turn in my heart. Step by step, season by season, I became a routine practitioner. I began to talk about it freely, and being a witch started to be just another aspect of who I was. I began to meet other witches like myself, people who practiced as one part of their rich and varied lives. I attended a few more covens, different from those where I’d started; this kind had bread and wine and children sleeping in the background. Yet even when coven meetings were blanketed in normality, I still fell back into practicing alone. It just felt right.

Wicca might be slightly disappointing if you’re looking for a grand initiation ceremony on which to hang your proverbial pointed hat. As I said before, there are as many ways to become a witch as there are witches. Don’t get too down in the dumps, though—there are a few traditions that are widely accepted. It’s up to you to find what fits best. In fact, if you Google “Wiccan initiation” you will find a bombardment of scripts, templates, and guidelines from which to choose. There are different tactics for different situations and different kinds of covens, as well as a number of options for solitary practitioners. These traditions do not vary much in the heart of what they are, but how detailed and involved they are depends on the witches carrying them out. Some ceremonies involve dedicating oneself to a specific god or goddess, some include a sort of personal introduction to the god and goddess, some are simply a welcome into the existing community. Most involve a core ritual of clearing a space, stating your intention, and declaring your willingness to continue a lifelong journey following the Wiccan creeds.

I had no ceremony that made it official. I hadn’t necessarily ever thought of creating such a moment; I didn’t start this journey with the intention of “ending” somewhere. However, as I became more and more comfortable with what I believed and how that belief was labeled, I became more comfortable with saying out loud that I was Wiccan. At that time and place in my life, those words didn’t always bring the warm and welcoming response I would have liked. More often than not, I was treated as if it were a passing phase or a trend I was following—not the true spiritual path I felt like I was on. At times, I let this shake me a bit, let it seep into those most vulnerable places in me and tell me that where I was finding my footing wasn’t really solid ground. Every time I felt my foundation shift a bit, I would be at once disappointed and angry at myself. I knew in my heart I had found a set of beliefs that felt true; I knew the path I was on was meant for me. I just needed to find the strength not to let the dismissiveness or derision of others make me feel lesser.

In most any other religion, I realized, there would have been a “moment”—a time when I formally decided to join the community, to proclaim my commitment to a set of beliefs. As a solitary practitioner, though, such a public ceremony wasn’t in the offing for me. But I thought perhaps the movement and meaning of that kind of ritual wasn’t about the outward declaration so much as the inward promise. I had been practicing for a handful of years, and I knew I wanted to continue. But thinking that to myself was different from taking the time to truly process what it meant and honoring that decision in a more formal way. So I began researching rituals of initiation into Wicca. As I mentioned earlier, I found no shortage of resources. I read books and looked through websites, but in the end I threw most of that research away.

In the end, in my quiet little house in the middle of a quiet little street, I just did what felt right.

With the Wiccan pentacle in mind, I carefully created five cairns in my backyard. I set out a small stack of stones for each point, representing the five elements: sky, earth, wind, water, and spirit, the topmost point. I sat down in the middle, the giant Kansas sky soaring above me. I stilled my body and breathed deep. I felt the earth anchor me and the stars pull me skyward. I felt my place.

I quieted my spirit and I honored it. I thanked what surrounded me for including me in the miracle of life, of creation and forward motion—for allowing me a place in the great turn of the wheel. I promised to walk that wheel as best I could, to recognize my place in this greater miracle, and to bring light and well-being to the world as best I could as I traveled my path. I promised the ground that held me and the sky that covered me that I would remember that I, in fact, possessed no special power, no access to ruling abundance. I was part of the turning wheel, a fragment of the greater abundance of nature. I would bring light wherever and whenever I could, as small as it might be; I would draw my strength from the moon and the stars and the sun. I would use the divinity within me to celebrate and honor the divinity that surrounded me. I would do no harm.

There was no one else present, no promises I made out loud. Yet from that moment on, I held in my heart the oath I had sworn to myself. I vowed to live what was true for me, to follow this path wherever it might lead, actively seeking peace and joy along the way.

It was all I needed. I had already lived a life surrounded by the kind of grand ceremonies that inspired awe, ones that took place in even grander settings: rites led by men in ceremonial garb holding up golden treasures and speaking in ancient languages I couldn’t understand. I had sat in the homes of gods, the archways soaring above me, their stories spelled out in giant statues surrounded by candles and windows of colored glass that made me feel small. I was ready to own my own power. I was ready to make a promise to myself that I would live in that power instead of seeking it outside of myself.

I would not ever let myself feel small again.

In the years since, I have faltered on that promise a number of times. I have, at times, let circumstances both within and without my control lessen me. I have let people make me feel unimportant and unnecessary.

And yet I come back to that long-ago promise again and again. It holds me up and reminds me of who I can be: I am divine. I am powerful. I am a vital part of an ever-expanding universe whose limits are unknown and indefinable. I am one child in a long line of survivors; my mere presence is their testament. I am made of the memories of trees, of the wind, of the sun as it shone upon generations of women and men who walked before me, leaving footsteps I never saw, but whose challenges and dilemmas, whose victories and triumphs were the foundation of who I was to become.

I am but a speck in a grand image I will never see the totality of, and yet I am a creator. I, too, am leaving footprints. I, too, am clearing the way for those who will come behind. I draw on the mothers who came before me; I reach toward the children ahead. I am not alone. I am not singular. I am worthy of the power of the universe. I am myself, and that is an amazing and fantastic thing to be.

When I falter, I call upon that, on the knowledge that I am a connection. I am part of something great and grand—not because I was placed here, not because I am a dream of someone’s fraught night, but simply because I have a place on the wheel of our world. I am intertwined with all before and all ahead of me. When I need strength, I call upon that.

Rarely has that strength served me as well, or been as important, as when I was in the hospital bringing my second child into the world. Up to that point, things had been pretty easy. Both of my pregnancies had made me feel more beautiful and more connected to the greater world around me than ever before. I was participating in the greatest cycle one could; I was growing life inside me. I reveled, amazed, in the fact that the love I shared with Sam had resulted in such a miraculous and extraordinary thing. I loved being pregnant; Sam joked, when our first child was weeks late, that I was refusing to share her with the world. He was not entirely wrong.

Samaire, our oldest, was born quickly, thanks to some encouraging via castor oil and my amazing midwife. I was only in labor for a few hours and only in the hospital for forty-five minutes before I was holding my small babe. The days following her birth were the most exhausting I have ever had, yet I remember moments in which I reminded myself that I was following a path that had been carved out by other women for millennia before. I was acutely aware as I rocked my babe, as I nursed her, as Sam danced her to sleep, that we were living out a story that had been written across the ages. We would survive, and we would thrive, as others were doing all around the world. That feeling was such a powerful thing: we were absolutely not alone.

Wylie’s birth was different. My labor with him was long and frightening. He was turned, essentially stuck, his heartbeat erratic. There were what felt like throngs of doctors and nurses in my hospital room, all ready to immediately jump into action once he was out. There was talk of prepping me for a C-section, then talk of it being too late. I was horrified and scared. I had torn a ligament in my rib cage and every push was torture, yet every push also felt inadequate. All I wanted was respite.

I knew something was wrong, and I was more frightened than I had ever been, but my midwife, Sandy, an older woman who I am convinced was some sort of shaman in a former life, leaned close to my face in the midst of the chaos.

“Misty!”

I tried desperately to focus on her. I made her my world.

“Where is this fear coming from? You are strong, and you will birth this baby when I tell you to. You can do this. You will do this. You are his mother. Bring him here!”

I made her voice my lifeline and I closed my eyes. I let myself fall into a black hole where there was just a singular act of intention. I drew from the deepest place in my heart, the place that was still feral and fierce—the place where my natural instincts overruled my fear—and I pushed.

I didn’t quite realize, at the time, how serious it was. All I knew was Sandy had told me I needed to get it done, and I could hear fierceness in Sam’s voice when he told me I had to do this for Wylie. The whole room seemed to crackle with energy as the nurses and doctors, waiting anxiously to get to work, cheered me on.

I heard very little of it aside from Sam and Sandy’s voices—Sandy telling me when or when not to push, Sam reminding me who I was working for. It seemed to go on forever, and with every breath I tried to fill my lungs with the strength of every mother who came before me, every goddess ever created. I would not fail. My body was absolutely weak at this point, but I was determined my spirit would remain strong.

There was a last, monumental push, and Sandy yelled, “Stop!” The room fell anxiously silent, and I waited for the sound of my son’s voice.

I didn’t get to hear it. The umbilical cord was wrapped around his neck; he was essentially trapped in a noose. Sandy expertly untangled him, and the nurses and the emergency room pediatrician surrounded him and Sandy. Still there was no cry, no breath. My heart stopped. I repeatedly asked if he was okay, and no one would answer me. I asked over and over, getting louder each time, but all I got in return was silence. My heart actually broke later when I asked Sam why he didn’t answer me and he replied, “Because I didn’t know, and I didn’t want to lie to you.”

Eventually Sandy grabbed Wylie by the ankle and turned him upside down, and as he hung there she smacked him harder than I ever would have thought possible from someone whose job it was to work with newborn babies. Again, she smacked him. Then she turned him over and sucked fluid out of his mouth, and I heard the sweetest sound possible: my baby cried.

I rejoiced, as have countless mothers before, grateful to have avoided the heartache some have had to endure. We had survived, all of us. Our story continued on, joining the legacy of stories that had come before.

It’s easy to look at the births of my children and see a point where our lives were forever altered: the moment I finally had them in my arms, when Sam finally got to feel their realness, to know them as I had for months. But change doesn’t always—perhaps not even usually—happen like that. More often than not, change creeps in slowly, washing away the past bit by bit until you look around and realize you have come to a new place.

As it turned out, Father Emil closing that rectory door was a beginning, not an end. My journey from there to here, all the time in between, that’s when I became a witch. I’m still becoming one, in fact. I may never be done with this journey and I am glad for that. There is always more to learn, more to practice, ways to be better.

I am a witch because I choose to make it so. I make the choice every day because it helps me be my most authentic self. I can point to that door all those years ago and see a beginning, but all the moments that followed are an undeniable continuation of that story; they have added up to where and who I am today. At times, I have stumbled. I have felt lost. I have felt alone and powerless. But I have always found my way back, because I am irrevocably tied to a vast and ever-expanding universe. Like that universe, I am inexplicable and indefinable and ever changing. I have the power of that first initial spark of creation inside of me, at my disposal.

So do you.

In my heart, I know this is true.