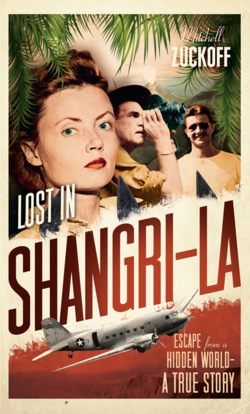

Читать книгу Lost in Shangri-La: Escape from a Hidden World - A True Story - MItchell Zuckoff - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter One Missing

ON A RAINY DAY IN MAY 1945, A WESTERN UNION messenger made his rounds through the quiet village of Owego, in upstate New York. He turned on to McMaster Street, a row of modest, well-kept homes on the edge of the village, shaded by sturdy elm trees. He slowed to a stop at a green house with a small porch and empty flower boxes. As he approached the door, the messenger prepared for the hardest part of his job: delivering a telegram from the United States War Department.

Directly before him, proudly displayed in a front window, hung a small white banner with a red border and a blue star at its centre. Similar banners hung in windows all through the village, each one to honour a young man, or in a few cases a young woman, gone to war. American troops had been fighting in the Second World War since 1941, and some blue-star banners had already been replaced by banners with gold stars, signifying a permanently empty place at a family’s dinner table.

Inside the blue-star home where the messenger stood was Patrick Hastings, a sixty-eight-year-old widower. With his wire-rim glasses, neatly trimmed silver hair, and the serious set of his mouth, Patrick Hastings bore a striking resemblance to the new president, Harry S. Truman, who had taken office a month earlier upon the death of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

A son of Irish immigrants, Patrick Hastings grew up a farm boy across the border in Pennsylvania. After a long engagement, he married his sweetheart, schoolteacher Julia Hickey, and they had moved to Owego to find work and raise a family. As the years passed, Patrick rose through the maintenance department at a local factory owned by the Endicott-Johnson Shoe Company, which churned out combat boots and officers’ dress shoes for the US Army. Together with Julia, he reared three bright, lively daughters.

Now, though, Patrick Hastings lived alone. Six years earlier, a fatal infection struck Julia’s heart. Their home’s barren flower boxes were visible signs of her absence and his solitary life.

Their two younger daughters, Catherine and Rita, had married and moved away. Blue-star banners hung in their homes, too, each one for a husband in the service. But the blue-star banner in Patrick Hastings’ window wasn’t for either of his sons-in-law. It honoured his strong-willed eldest daughter, Corporal Margaret Hastings of the Women’s Army Corps, the WACs.

Sixteen months earlier, in January 1944, Margaret Hastings walked into a recruiting station in the nearby city of Binghamton. There, she signed her name and took her place among the first generation of women to serve in the United States military. Margaret and thousands of other WACs were dispatched to war zones around the world, mostly filling desk jobs on bases well back from the front lines. Still her father worried, knowing that Margaret was in a strange, faraway land: New Guinea, an untamed island just north of Australia. Margaret was based at a US military compound on the island’s eastern half, an area known as Dutch New Guinea.

Corporal Margaret Hastings of the Women’s Army Corps, photographed in 1945.

By the middle of 1945, the military had outsourced the delivery of bad news, and its bearers had been busy: the combat death toll among Americans neared three hundred thousand. More than one hundred thousand other Americans had died non-combat deaths. More than six hundred thousand had been wounded. Blue-star families had good reason to dread the sight of a Western Union messenger approaching the door.

On this day, misery had company. As the messenger rang Patrick Hastings’ doorbell, Western Union couriers with nearly identical telegrams were en route to twenty-three other star-banner homes with loved ones in Dutch New Guinea. The messengers fanned out across the country, to rural communities and urban centres including New York, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles.

Each message offered a nod towards sympathy camouflaged by the clipped tone of a military communiqué. Signed by Major General James A. Ulio, the Army’s chief administrative officer, Patrick Hastings’ telegram read:

THE SECRETARY OF WAR DESIRES ME TO EXPRESS HIS DEEP REGRET THAT YOUR DAUGHTER, CORPORAL HASTINGS, MARGARET J., HAS BEEN MISSING IN DUTCH NEW GUINEA, THIRTEEN MAY, ’45. IF FURTHER DETAILS OR OTHER INFORMATION ARE RECEIVED YOU WILL BE PROMPTLY NOTIFIED. CONFIRMING LETTER FOLLOWS.

When Owego’s newspaper learned of the telegram, Patrick Hastings told a reporter about Margaret’s most recent letter home. In it, she described a recreational flight up the New Guinea coast and wrote that she hoped to take another sightseeing trip soon. By mentioning the letter, Patrick Hastings’ message was clear: he feared that Margaret had gone down in a plane crash. But the reporter’s story danced around that worry, offering vague optimism instead. ‘From the wording of the [telegram] received yesterday,’ the reporter wrote, ‘the family thinks that perhaps she was on another flight and will be accounted for later.’

When Patrick Hastings telephoned his younger daughters, he did not hold out false hope about their sister’s fate. Outdoing even the Army for brevity, he reduced the telegram to three words: Margaret is missing.