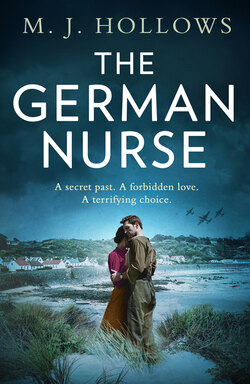

Читать книгу The German Nurse - M.J. Hollows - Страница 9

Chapter 1 19 June 1940

ОглавлениеGuernsey was beautiful in the summer: the rolling green fields, the vivid blue sea. It was what drew most people here, taking the boat from Weymouth, or a short flight across the Channel. It was a perfect spot for a holiday, but fewer people were visiting by the day, since the British Government had declared war on Germany. Far closer still was the coast of France, visible on the horizon to the south of the island.

The beauty was the only thing Jack could think about as he left the house he shared with his mother and grandparents. His mother’s voice still resonated in his ears, speaking those hard and damning words.

‘Don’t make the same mistakes I made. Not with that woman! Jack? Jack?!’

He caught the door before it slammed shut, then let it click softly against the wooden frame. He didn’t want to exacerbate things and draw the neighbours’ attention. Taking a deep breath, he tried to forget his mother’s words and stepped away from the house. The further away he was from there, the less it would play on his thoughts. It was a fine June day, bright blue sky and barely a cloud in sight, and his mother’s mood couldn’t change that. It would take something far worse, and even though war was brewing on the horizon, it hadn’t reached them yet. Who knew if it even would?

Their house was typical of the buildings on George Street at the edge of St Peter Port, built from a stone that gave it a mottled, irregular look, and roofed in grey slate tiles. Some of the houses in the terrace were plastered and painted white, but Jack’s grandparents had left theirs as natural as possible, less difficult to maintain and still impressive. They had once owned a farmhouse, as they never grew tired of telling him, but as his grandfather’s health had deteriorated they had moved closer to the town.

He had been a great man with a booming laugh, always telling stories and like a father to Jack, but now he was a gaunt man almost always confined to his bed. The row of houses lined the way down to the harbour, and Jack knew every occupant by name. He stood for a moment looking at the navy-blue-painted door and wondering if his mother would follow him after their argument.

He and his mother had argued a lot more recently, but he knew deep down that she was only concerned. She meant well, but sometimes she didn’t think before speaking. Like everyone, she was worried about what might happen to them. The ever-looming shadow of war seemed to grow closer every day. She couldn’t forget the last war, how it had affected them all, and it had affected her more than most.

He turned and picked up his bicycle from the wall; he was going to be late if he didn’t hurry. He wished he had time to go and see Johanna. Seeing her would cheer him up.

The sun beat down and he began to sweat. His clothes were close and hot, and it would be even worse when he put on his uniform at the police station. But it gave him a sense of pride to wear it, a sign that even in his short life he had already accomplished something many others could only dream of.

People were going about their business as usual in the morning, heading to work at the shops and eateries, fishermen coming back from overnight hauls, and he greeted them with a smile and a nod as he cycled past. They liked seeing their local policeman on the streets, looking after them, especially in these dark times when everyone was nervous and never far from fear. He was here for them. He was a public servant, no more, no less. He had dedicated his life to helping other people, and no matter what happened he would never forget that.

*

Jack entered the police station and the hot summer sun was immediately blocked out. There was always a musty, damp smell to the interior, as if it had been built on top of some sort of stream. It was muggy and even the collar of his linen shirt chafed at his neck.

‘Morning,’ William – the sergeant on the desk – called, looking up from some paperwork. ‘You’ve heard then? They’re in the briefing room.’

‘Heard what?’ Jack leant on the other side of the desk, waiting for the sergeant to explain. Normally the pair of them only exchanged pleasantries, but there was a look in William’s eyes that Jack couldn’t quite describe, like he was staring right through him.

‘The chief’s called everyone in,’ he said a moment later. ‘Something big’s happening. I thought you’d got the telephone call. You’d better hurry.’

Jack nodded and headed through the main doors and into their changing room. He tried to spend as little time in the station as possible, preferring the wide-open grasslands of the island. He asked for patrol shifts that took him on the long walks that many of his colleagues would rather avoid.

Jack had heard nothing of the meeting that William had mentioned and it pulled at his imagination, as he folded his clothes into a cupboard. It could be anything, but his mind immediately thought the worst. Some hoped the war would stall far away in France like the last one, but many still worried. They wondered what to do, some leaving the island already and others stockpiling food and supplies. Even the soldiers had no idea. He thought of them as he pulled his uniform on. Their fear must be worse than the Islanders, not knowing when they would be called to fight.

The newspapers had reported on the happenings in mainland Europe, and every time Jack thought of it he could feel a tightening in his chest. No matter how often he told himself to be calm, that everything would be all right in the end, he couldn’t ignore that indefinable feeling of dread.

Fully uniformed, Jack pushed open the door of the briefing room. He was immediately hit with the smell of cigarette smoke and body odour. The room was dark, with no natural light, only the faint glow of the kerosene lamps. The building only had electric lighting upstairs.

The room was full, seeming to contain the entirety of Guernsey’s police force, all thirty-three men.

‘Glad you could join us, Constable Godwin,’ a deep voice said. The chief officer didn’t even bother to look at Jack as he leant against the wall at the back. The chief’s voice was thick and he cleared it, passing the phlegm into a white cotton handkerchief that he kept in his breast pocket. ‘Well,’ he continued. ‘Now that everyone is here we can begin.’ He picked up a few pieces of paper from his desk and shuffled them, apparently looking for something in particular. He fumbled with his glasses. ‘The next few days are going to be incredibly difficult for us,’ he said, fixing each of them with a look before moving on. ‘The news we’ve all been anticipating has finally arrived. The envoy returned from the mainland this morning.’

There was a slight shift in the room as the local policemen objected to the description of England as the mainland. Jack often made the same mistake, treating Guernsey as an extension of England when most of the locals thought of themselves as their own country. The chief didn’t seem to notice as he continued.

‘The Prime Minister, Mr Churchill, has ordered the withdrawal of all military forces on the island,’ he said, looking them all in the eye one after the other again, letting the implication of his words settle in. ‘The British Government have decided that the islands are not worth the resources needed to defend them.’

There was a gasp from the assembled policemen. They glanced at each other, looking for reassurance. ‘Does it really say that, sir?’ someone asked amongst the mutterings.

‘Not explicitly, but that’s not the point. We’ve often been on our own. I don’t see this as any different. We all have our jobs to do. We’ve also been asked to assist in whatever way necessary, to expedite their withdrawal from the island. There is expected to be a panic when the Islanders find out the army is leaving, and many will want to travel to the mainland. The states want this to be organised as efficiently as possible, and the press is already preparing to circulate the details in today’s papers.’

He raised a copy of the Star. ‘EVACUATION,’ it read. ‘ALL CHILDREN TO BE SENT TO MAINLAND TOMORROW. WHOLE BAILIWICK TO BE DEMILITARISED.’ By comparison the Guernsey Evening Press had a more measured account of how the evacuation was going to be conducted. There was a sigh from someone to Jack’s right. ‘They’re abandoning us and we’ve gotta help them do it? Fantastic.’

‘Less of that, Sergeant.’ The chief officer fixed Sergeant Honfleur with a pointed stare over the top of his glasses. ‘We’ve all had to follow orders we didn’t agree with before; this is no different.’

Jack only knew some of the soldiers by name, Henry and the others, and they were part of the local militia that had now been disbanded. Some of them had gone with the army to enlist in England and he couldn’t shake the horrible feeling that they were leaving them behind. The Islanders had known the war would come for them sometime, but the forces that were stationed here were supposed to be for their protection.

‘What now, sir?’ the sergeant asked, crossing his arms and leaning back against a desk. The atmosphere was tense and the policemen shifted in their seats. William played with his watch, and David squashed a cigarette in an ashtray as he lit another.

‘Now, with luck, the lack of armed forces here will mean that even if the Germans get this far, they’ll leave us alone.’

‘Let’s hope you’re right, sir.’

‘Well, we all have our normal work to do and you all have a decision to make. The islands are not defensible. We don’t know whether the Germans will come, but it’s a possibility.’

‘How do we know, sir? What will they want with us? If the islands are indefensible, it’d be the same for them.’

‘Maybe they’re after your potato patch, sir.’ That was PC David Roussel, a grin stretched across his face. They all laughed, lowering the tension in the room, but it was cut short by a glare from the chief.

‘The states have appealed to the government to mount an evacuation.’

There was another murmur around the room, and Jack looked across at David who shrugged in response. The chief cleared his throat again. ‘They’ve agreed,’ he said. ‘But those wanting to leave have to be ready immediately. I’ve just received a telegram. The boats for the children are coming tomorrow. Any child who needs evacuating to England has to be ready to leave by tomorrow morning. The first boats will arrive at two-thirty in the morning. Children of school age and under can register to be taken to a reception centre on the mainland.’

‘What about their parents, sir?’

There were parents in the room, and they sat up straighter than before. He shuffled through the notices again, then finding the one he wanted he pushed the glasses up on his nose and took a closer look. ‘Anyone wishing to be evacuated will have to register with the authorities and wait to see if there is enough room on the boats. There is no guarantee that everyone will be evacuated, except for the children.

‘Those men wishing to join the armed forces on arrival in England may also register.’

He dropped the papers to his desk and looked at them over the rim of his glasses.

‘Now, as honourable a decision it may be to go and join up in England, let us not forget the people whom we serve here. If you all go, what am I to do then? Even if the Germans don’t come there will be anarchy on the island. Please consider that before making your decision. I expect every man to do his duty and continue in service of the island. If you leave, there will be no job to return to.’

There was a general hubbub as the policemen talked amongst themselves. The islands had been conquered a long time ago when the English had taken them from the French. It didn’t mean that it would happen again. Jack couldn’t imagine it. The islands were peaceful. If they didn’t fight the Germans then maybe they could just get on with their lives in peace. Jack wouldn’t leave anyway. He needed to be here. His mother had no one else, except his grandparents, and he had to look after them as well. They all relied on him. Then there was Johanna.

The chief cleared his throat. ‘Dismissed,’ he said. ‘Get to work.’

The chief came over to Jack as the others were leaving and pushed his glasses back up onto the bridge of his nose. Through them his eyes were large and beady. They reminded Jack of an insect, and he fought a smile that threatened to turn the corner of his lips. Smirking at his superior officer wasn’t a good way to start the day, no more than arguing with his mother.

‘I remember your thoughts on war, but surely you aren’t against helping these chaps get on their boats, are you?’

Jack didn’t say anything. A few misplaced comments from Jack in the past and the man had assumed so much. He had learnt since then that it was easier to let him talk. The chief liked the sound of his own voice. ‘We all have to do things we don’t like in the line of duty. I have a special request of you, Jack.’

‘Yes, sir?’ he asked, already dreading what it might be.

‘I want you ready first thing in the morning. On your way in, check on the evacuation of the children; make sure they have everything they need and that no one is causing trouble.’

‘Yes, sir.’ It wasn’t the duty he had been expecting, but it could have been a lot worse.

‘Good. Then I want you to be the first one down at the harbour. You and your colleagues will erect barricades to ensure that only those who are registered can board. We have to be careful – I have a bad feeling about this.’

It was true, things were only going to get worse as the tension on the island rose and people panicked. The chief nodded over his glasses and left Jack to his thoughts. He would need a good night’s sleep, but he still had a whole day of work ahead. He sighed and went to find the sergeant to enquire about his duties.

*

After the briefing it had been a quiet day, which seemed to drag on into eternity as Jack patrolled the island, keeping an eye out for any trouble and helping with menial tasks when he had nothing else to occupy him. Many had been busy making preparations for the evacuation as word had spread quickly. Finally, later that evening, he returned home, ready for a good night’s sleep. His legs ached and his feet were sore from standing all day, something that he thought he would never get used to. He didn’t know why the boats had to come so early, but then he never really understood the methods of government. Leaving the island defenceless didn’t seem right, but he had to believe they knew what they were doing, otherwise he might as well just throw his uniform away. He had worked so hard to get that uniform in the first place; he wasn’t going to give it up now.

His way home took him past the town hall, which had been turned into a registration office for the evacuation. Jack had been past earlier in the day while they were preparing and now there was a long queue around the building. It moved slowly, but the tension was clear as people stood closer to each other than they would do otherwise, rushing forward every time a gap opened. Some groups chatted quietly; others stood in silence.

There was a scuffle between two men, and one of them was knocked to the ground. ‘I was here first,’ the standing man shouted, moving closer to his victim and pulling back a foot to strike. There was a gasp from the surrounding crowd, a quick intake of air as they recognised Jack, even out of uniform. The attacker hesitated, then reached out a hand to help his victim up. The other man refused and went to stand further back in the queue as his attacker eyed Jack warily. The knuckles of his right hand were grazed and pinpricks of blood stood out. Jack made a mental note to check on the man later, in case he caused any more trouble.

He nodded at the man, then worked his way around to the front of the queue, to see a man come back out of the door to the registration office, pulling his wife behind him. He didn’t see Jack as he bumped into him and pushed his way past without so much as a ‘sorry’. Given the stress that people were feeling, he decided to let it go. People in the queue looked after him, their eyes wide.

He flashed them a smile. ‘Good evening,’ he said, touching the brim of his hat. No one paid him any notice, but his smile didn’t falter.

A woman appeared around the corner, walking at pace. She wore a light beige summer dress, which fluttered in the breeze, and a matching hat. It was a second or two before he fully recognised her, as he was lost in his own thoughts. ‘Johanna,’ he breathed, before stepping aside to make sure he was in her path.

She almost walked around him, shaking her head, before looking up and stopping in her tracks. ‘Jack?’ she asked, in the familiar way she said his name. Jacques. He loved the way she said it, with the soft ‘J’ much closer to the French. ‘What are you doing here?’

She reached out a hand and rested it on the crook of his arm, and smiled.

‘I was on my way home.’ He smiled back at her, stroking her hand. ‘I could ask you the same?’

‘Me? Bah!’ She snorted, remembering herself. ‘I joined this queue to see if they would take us to England. But they said no and called me an “enemy alien”. An enemy indeed! First they lock me up, now when they release me, this. What harm could I possibly do to their precious country? We have the same enemies! But they treat me like an enemy, just because I’m German. They wouldn’t even let me work as a nurse, despite my training.’

Her cheeks were red and she shook her head, letting go of his arm. When the war had started the states had not been sure what to do with foreigners living on the island, and when the Germans were getting closer to the islands they had locked up all the Germans in case they were spies. Johanna had only just got out. Jack looked around them and caught the eye of several in the queue watching their conversation. Without thinking he took a hold of Johanna’s arm and pulled her gently along the street, down an alley between a pair of buildings, out of view and earshot.

‘We’re best talking here,’ he said. ‘Who knows who’s listening?’

‘Why does it matter?’ she asked, looking up at him.

‘These people are worried.’ He gestured back the way they had come. ‘They don’t know what to do and they don’t know what will happen. If we’re not careful their worry may become anger.’

‘I don’t understand,’ she said, a frown crossing her brow. It was that look that had first attracted him to her, the look of a furious intelligence. The curls of her auburn hair bounced as she shook her head. ‘Why can’t we go as well?’

He sighed. It wasn’t that the question was a bad one, he just didn’t know what to say. In a perfect world they could just live out their lives on the island in peace. He took hold of her hand. He wanted to tell her he would run away with her, that he would always protect her, but where would they go? Europe was at war, and she wasn’t allowed into Britain.

‘There are conditions that need to be met before someone can register,’ he said at long last. ‘There’s not enough room in the boats for everyone. It’s only for parents who wish to accompany their children, and even then, I’m not sure they can guarantee space. And foreign nationals aren’t being allowed into the country right now.’

‘So they expect me to stay here?’ She struggled her hand out of his grip and paced across to the other side of the alley. She leant against a wall, her back on the painted stone, and closed her eyes. ‘What happens when the Germans come? I’ve already run from them once. What next? What if they find out I’m a Jew?’

Again, he didn’t have the answer, but based on her body language he didn’t think that she expected one. He moved closer to her, careful not to startle her. ‘We don’t know if they will come,’ he said. ‘The states are hoping that they will just avoid us, especially when the army leaves. Besides, I want to stay here. I don’t want us to go anywhere.’

‘You haven’t seen the things I’ve seen, Jack.’ It almost felt like an accusation, like somehow because he hadn’t been there he couldn’t possibly understand what she was thinking or feeling. She was probably right, but if she didn’t confide in him, then how could he ever understand? She had mentioned her past, but had refused to say more when he asked. She didn’t want to talk about it, but how was he supposed to understand her if she didn’t? He often wondered what had happened to her in Germany, and he had heard plenty of rumours, but she would not speak of it.

‘They won’t stop at the French coast,’ she said, seeing his hesitance. There were tears at the corners of her eyes.

‘What if they don’t?’ he asked. ‘We can’t worry about that now. We have to take each day as it comes. They are just as likely to leave us alone. What need do they have of the islands?’

‘You never worry. How can you be so calm, Jack? Teach me.’ She reached out a hand to him as if beckoning, and he took a step closer. He intertwined his fingers with hers and thought about pulling her into an embrace, but stopped.

‘When I was old enough to understand that my father had died, I was angry,’ he said, his voice a soft whisper. ‘It took me a long time to realise there was nothing I could have done.’

The town hall bell suddenly struck, ringing out across St Peter Port. It was getting late. He screwed his eyes shut, feeling suddenly weary.

‘I have to go,’ he said with a sigh. ‘To get some sleep before the morning. The boats are coming at two-thirty in the morning, but the attorney general has managed to persuade them to delay boarding until six.’

Johanna let go of his hand and let out a deep breath. He tried to take hold of her again, but she pushed herself away from the wall and walked towards the end of the alley.

‘Where are you going?’ Jack called after her.

‘To the hotel,’ she shouted back over her shoulder. ‘They need volunteers. At least I can be useful!’ Johanna walked away, leaving him alone in the side street.