Читать книгу Guantánamo Diary - Mohamedou Ould Slahi - Страница 11

ОглавлениеThe End of the Story, and an Introduction to the New Edition

by Mohamedou Ould Slahi

1.

Every time we had a hurricane warning in Guantánamo Bay, I had the same daydream. I imagined the prison camp wiped away and all of us, detainees and captors alike, fighting side by side to survive. In some versions I saved many lives, in others I was saved, but somehow we all managed to escape, unharmed and free.

This is what I was imagining on October 7, 2016, when Hurricane Matthew was building in the Caribbean. The forecast was predicting a direct hit on Guantánamo, so the camp command decided to move all the detainees, about seventy of us, to Camp 6, the safest facility in GTMO. I was told that my belongings might not survive the hurricane, so I took my family pictures, my Koran, and two DVDs of the TV sitcom Two and a Half Men. The NCO in charge, a sympathetic Hispanic sergeant first class in his forties, arranged for another detainee to lend me his portable DVD player, but the machine died within minutes.

Outside my cell, an argument broke out between one of the detainees and the guards over the temperature in the block, an argument we all knew was futile, but the detainee had started and now couldn’t stop.

“You Americans, even if I treat you as human beings, you don’t respect me,” he was yelling.

“We can do this the easy way or the hard way,” the guards were yelling back. I did my best to tune them out, and I spent the night listening for the sound of the heavy wind battering the cell, daydreaming another dramatic escape.

The structure was so strong that I never even heard the storm. But in the morning the camp was buzzing with rumors about detainees who were going to leave. One rumor said that there was a comprehensive plan that I was going be resettled along with Abdul Latif Nasir, a Moroccan detainee, and Soufiane Barhoumi from Algeria. We had all heard so many rumors over the years that turned out to be just that, rumors, that we knew not to celebrate; this would prove to be another.

For me, though, the real news came that afternoon. The bearer was our brand-new officer in charge. She had just taken over and I had not even met her yet, but now this army captain was sticking her head through my bin hole and giving me the broadest smile I’d seen in many years.

“Do you know that you’re going to leave soon?” she said. It was the best introduction to a new OIC ever: I’m taking over, and you’re going home.

I was moved to a different cellblock. I met with representatives from the International Committee of the Red Cross, who officially informed me that I was to be transferred. The U.S. government dreads the mention of detainees being freed, so it uses its own vocabulary of “transfer” and “resettlement,” as if we were cargo or refugees. Yazan, a Jordanian representative I knew from previous ICRC delegations, asked if I would accept resettlement to my home country of Mauritania. I told him I would take any transfer I was offered, quoting the title of a Chris Cagle country song: “Anywhere but Here.” The next day, my attorneys Nancy Hollander and Theresa Duncan called me from the United States to confirm the news. Only then I could say to myself, Now it’s official: I’m leaving this prison after so many years of pain and humiliation.

“You have the Gold Meeting tomorrow,” the new OIC told me when I got back to my cell after the call. Her smile still hadn’t faded.

The “Gold Meeting” takes place in Gold Building, a structure that was built for interrogation. At first, the interrogations there were not so bad by Guantánamo standards. We answered all kinds of questions from FBI, CIA, and military intelligence officers, as well as investigators who came from around the world at the invitation of their American colleagues. But the building was given a face-lift in 2003 and then was used along with the so-called Brown and Yellow buildings for torture sessions. It was in this same Gold Building that I spent many sleepless and cold nights that year, shivering in my shackles, eating countless tasteless MREs, and listening to “Oh say can you see, by the dawn’s early light” in an endless, repeating loop. Now the bushes around the building were growing out of control, and the old Delta Three camp next door looked like a graveyard. Romeo block, where I spent my last days before I was dragged into a boat in a fake kidnapping, existed only in bits and pieces. Everything was old and rusted and dirty. It looked like a scene after one of my hurricane daydreams.

Inside Gold Building, though, nothing had changed. Its rooms were now assigned for FBI and Army Forensics, for phone calls to lawyers, and for meetings with the ICRC. But they were still set up the same way, with their one-way mirrors and the adjacent control rooms where a bunch of idle Joint Task Force (JTF) personnel would sit chewing on their cold cheese-burgers, watching me, and asking themselves how I’d ended up in this place. Even the smell was the same: at the first hint of it, I was hearing the sound my heavy chains made the day I was dragged down the corridor to a room where I would meet Sergeant Mary, one of the main interrogators on my so-called Special Projects team.

One night in August 2003, I sat shackled in one of those rooms listening to a phone conversation one of my interpreters was having. She was calling her family back in the United States, and she had forgotten to close the door behind her. English seemed like her first language, but she was speaking to her family in Arabic, with a soft Lebanese or Syrian accent. To hear her casually sharing mundane stories about life in GTMO, very relaxed, completely oblivious to the man suffering next to her, was surreal, but it was just what I needed on that cold, unfriendly evening. I wished her soothing, musical conversation wouldn’t end: she was my surrogate, doing for me what I couldn’t do for myself. I saw in her a physical and spiritual conduit to my own family, and I told myself that if her family was doing well, my family must be doing well, too. That I was mitigating my loneliness by listening to someone else’s intimate, personal conversation posed a moral dilemma for me: I needed to survive, but I also wanted to keep my dignity and respect the dignity of others. To this day I am sorry for eavesdropping, and I can only hope she would forgive my unintentional transgression.

Now, for the “Gold Meeting,” my interpreter was a small brown Arab-American in his early thirties, with short, receding black hair.

“Are you from West Africa?” he asked in Arabic as I was led into a room and shackled to the floor. My ankle chains provided a musical backdrop to our conversation, echoing throughout Gold Building. What do other people think about us being shackled? I always wondered in these situations. Do they find it normal to interact with a restrained human being? Do they feel bad for us? Do they feel safer?

“Yes, Mauritania,” I answered in Arabic, smiling.

“Do you understand when I speak?” The room was packed with people I didn’t know, mostly high-ranking military officers, and he seemed eager to show how essential he was to the proceedings.

My escort team pushed the desk close enough that I could lean on it and hide my shackled feet underneath, giving the impression of a relaxed, free man. A recent picture of me adorned the door.

We waited. Like everywhere on earth, the big boss did not need to show up on time. Finally the voice of a service member, shouting as if an assault was under way, roused the room to its feet.

“Colonel Gabavics, JDG Commander, on site.” The door opened and there he stood, in the flesh. It was the first and last time this man would speak to me.

“You will be transferred to your country in one week. Do you have any questions?” Because I could hardly imagine life outside Guantánamo after so many years of incarceration, I had no idea what questions to ask. I made a request instead. I told the colonel that I wished to bring my manuscripts with me—I wrote four in addition to Guantánamo Diary during my imprisonment—and some other writing and paintings I had made in classes I took in GTMO. I said I would also like to take several chessboards, books, and other presents I had received from his predecessors and from some of my guards and interrogators, gifts that had great sentimental value. I named those who had given me these presents, hoping he would honor my request for the sake of his friends.

“I’ll talk to the people in charge,” he said. “If it’s okay, we will send them with you.” I thanked him, smiling, wanting the meeting to end on that good note and not to screw things up by saying things I wasn’t supposed to say.

The colonel disappeared as quickly as he came. The escort team took me to the room across the hall, where I found two women in uniform. A skinny brunette Army sergeant sat in front of an old Dell desktop that was running Windows 7. She kept smiling, even though her computer was a classic recipe for frustration; she typed everything at least twice, and the PC kept passing out on her. On her right sat a woman who seemed to be her boss, at least by rank, a short blond Navy lieutenant with a neat ponytail. She was friendly, too, and even asked my escort team to remove all my shackles.

There followed a photo shoot that had me posing five different ways: face the camera, face right, face left, and forty-five degrees to both sides. I had to give my fingerprints in about a dozen ways on an electronic pad. They recorded my voice as I read a page written in English: “My name is fill in the blank. I’m from fill in the blank. I love my country,” and the like. That was as literary as it got. I must have been nervous, because I passed this voice recognition test only on the second try. Through it all, the sergeant struggled to save my biometric data into the old computer.

My escorts restrained me again and took me to another room, this one with an FBI team.

“If you promise to behave, I’ll let them take off your restraints,” a Turkish-American agent said with an honest smile. The FBI team fingerprinted me, using the old method of sticking my fingers in ink and pressing them on a paper. It was a long, tedious process, which gave me time to try out my Turkish with the agent. As we talked, his finger slipped and made its own print on the paper. He freaked out, grabbed a fresh paper, and we started again.

“I hope this will be the last time you ever have to do this,” he said, laughing and handing me some sandy soap to clean my fingers. There were four other standard-issue FBI agents in the room, two middle-aged women and two other men. The whole team was having a good time with me.

“You don’t need to hope,” I assured him. “You can bet your last penny.”

I was taken to my new home, the transfer camp. I had seen this camp a million times: it was right next to the Camp Echo isolation hut, where I lived for twelve years. If I believed in conspiracy theories, I would have said that the government purposely put the transfer camp right next to my cell for all those years to make me suffer even more. So many detainees were transferred out during those years, and I would be the last one to bid them farewell. We would speak to each other through the fence that separates the two camps. It was comforting to see innocent men finally being freed, and I was happy for every detainee who passed through the transfer camp, but it stung to watch them leave. Now that detainee was me, and I couldn’t help but feel guilty. It hurt to think of leaving other innocent detainees behind, their fates in the hand of a system that has failed so badly in matters of justice.

“We missed you, 760,” one of my old regular Camp Echo guards greeted me as I was unstrapped from the seat of the transport van. As we walked through the camp, a small, blond female sergeant with a southern accent went over the new rules.

“You can go anywhere you like in the camp, but you’re not supposed to cross that red line. Honestly, I don’t care if you do, but don’t hang out long, because if they see you on the camera, we could get in trouble,” she told me as she led me to my new home. “We push the food cart all the way to the white line,” she went on, going over procedures I would be hearing for the last time. In one of the strange tricks of Guantánamo, the sergeant and I walked and conversed like old friends, completely overlooking the fact that I was shackled.

Because of the hurricane, many of the mesh sniper screens on the windows had been removed from the Camp Echo huts, and the contractors—mostly so-called Third Country Nationals, who make very low wages and struggle to maintain the facilities—had not finished putting them back up. From my cell, I saw a whole world that had been surrounding me for many years, so close but so elusive: the maze of interrogation rooms; Camp Legal, where detainees meet their lawyers; the hut where the translators and teachers watched TV, waiting for their next encounter with detainees; and the two buildings where detainees come to call and Skype with their families. In a parking lot nearby, people parked their big American vans and climbed out of them, looking bored and sick of their tedious jobs. Through the fence that separates my old Camp Echo Special hut from the transfer camp, I could see that my garden was gone, except for the untended grass and the few trees whose resilience is matched by those of us detainees who had managed to remain in one piece.

For the next several days, JTF staff kept pouring in to brief me about what was happening with my transfer. The news was coming thick and fast, from guards, from the OIC, the NCO in charge, from an officer from the Behavior Health Unit, and from the senior medical officer. Everyone brought good news. I was told that my items were packed and had been sent to the transport people and that they would be loaded onto the plane with me. An Air Force captain from the BHU said that she had been planning to see me the following Monday, but she now doubted I would still be here. The senior medical officer, a Navy captain, came in person to hand me malaria medication, a sure sign that my departure was imminent. In between these visits, I spent most of my time talking with the guards about what kinds of electronic gadgets I would need to acquire when I got out, and the best ways to watch all the movies I had been forbidden to watch in GTMO. They taught me about streaming sites like Netflix and Putlocker, and even about illegal downloading.

And then the day came: Sunday, October 16, 2016. All day, people in uniform kept coming and going, most saying little, if anything at all. It was surreal—as if the whole base now had only one detainee to worry about. My new favorite OIC showed up again and again with her broad smile. My night shift didn’t show up at all.

“Where’s the other shift?” I asked one of the guards, a guy who had been tutoring me on how to deal with the new technologies that were waiting to overwhelm me.

“I would love it if they let me be the one leading you out of here, and the last one to say goodbye to you,” he said. The specialist’s prayer was answered; he would put the shackles on me for the last time.

He grew less talkative as the afternoon wore on. Everyone seemed solemn, and a complete and utter silence descended when the smiling captain came to me and said, “You have two hours left. We’re going to lock you down.”

“Now it’s for real,” I told myself. I went inside the cell and heard one of my guards trying to lock the door manually, a very familiar sound. Whenever civilians like teachers or contractors would come from outside the camp, we would be locked like this inside our cells. I took a shower and shaved. I dressed in the new detainee uniform I had been given. My old clothes, like all my belongings in the cell, had to be left behind. I tried to watch TV, then read a book, but I could do neither. I just kept pacing inside my room, praying and singing quietly. It was the longest two hours of my entire life.

“Are you ready?” the captain finally said as she looked through my bin hole.

“Yes.”

“Can you stick your hands outside the bin hole?” one of the guards asked.

I offered my hands, and the guards put the shackles on my wrists, gently yet firmly, asking whether the cuffs were too tight. I shook my head. After my hands were restrained, the guards opened the door to finish my upper body and my legs. I was shocked to see how many people could fit in that small place. I saw people in uniform everywhere I looked, including the overeager translator from my meeting with the colonel. But this time he watched and said nothing. The only place I’d ever seen such solemnity was when I attended funerals. I hardly spoke, just nodding when someone asked a question.

The female captain was guiding the guards, telling them what to do next.

“Take him to the red line.”

The red line was about sixty steps away from my door. I felt as though I could hear people’s hearts beating as clearly as the Black Eyed Peas’ “Boom Boom Pow.” My escort team seemed nervous, and they went too far. The captain had to shout at them, “Do not cross the red line. Step back. Step back.” The guards obeyed, leading me backward and stopping just in front of the line.

A huge gate opened, and a new escort team emerged. They quietly took control of me from my guards. They did not do the usual inspection of my restraints; they did not say anything as they led me outside the gate.

Another group was gathered there, including the senior medical officer and a very tall white man in uniform who was wearing a backpack and whose rank I couldn’t see. It was dark outside, but I could see that he was holding a printout with a recent picture of me. He placed the picture beside my face, looked back and forth, and shouted, “Identity confirmed.” The whole team looked as if they’d just arrived from a long trip. They all seemed sleepy, even the small black woman who’d been pointing her video camera at me from the moment I left my cell. A skinny blondish specialist would join her in the bus that transported us to the airport, and they would take turns on the camera all the way to Nouakchott.

“Do you have any complaints?” the senior medical officer asked.

I shook my head. “No.”

A slight smile broke across his face, and he almost shouted, “760, I declare you fit to fly.”

We passed through two more gates. We boarded a bus that drove onto a ferry, and the bus danced like a dervish in a trance as the ferry crossed the bay. We pulled out onto the airstrip and up to the back door of a cargo plane big enough to drive a truck inside. The engines were roaring, and everyone had to shout to convey the simplest message. I was led up a long cargo ramp. As soon as we stepped inside the plane I was earmuffed and blindfolded, just as I had been when I was taken from Bagram Air Base to Guantánamo Bay. This time, though, there was no beating, harassment, or degradation. I was strapped into a hard seat that was set nearly at a right angle and that did not recline. I didn’t dare to complain for fear someone would change his mind and take me back to the camp. I lost track of time during the flight, fighting against the pain that began in my back, spread to my ears and head, and soon overwhelmed me from all directions.

The plane landed with a heavy thump, and I felt someone peeling off my blindfold and my earmuffs. The first thing I saw was a digital clock on the wall of the plane in front of me—a little past 14:00, it read—and a bunch of half-asleep recruits who looked like they had not had their best night. I felt gentle hands playing with my shackles, starting from the middle and working up and down.

“Did we arrive? I asked tentatively, barely in a whisper.

“Yes,” a guard beside me said.

“Is this the local time?”

“Yes.”

There was no mistaking the Mauritanian weather. It was a good day, not too hot—just the right, warm welcome I needed. I was escorted, unshackled, down the ramp and onto the tarmac, where several Mauritanian government officials and an American official waited. We exchanged casual greetings, and my U.S. service member escorts went directly to stand in formation near their countryman. After a few pleasantries, the American started toward his car.

“Who’s that?” I asked one of the Mauritanians.

“The U.S. ambassador,” he said.

“Can I say hello to him?” I asked.

He dispatched a man standing near him. The ambassador came back to me and we shook hands.

“Welcome home,” he said.

2.

As a child, I always wanted to write and teach. My role models were my teachers. When I came home from school, I would gather the kids from my neighborhood who either couldn’t afford school or whose parents didn’t see it as necessary, and offer them classes for free, re-creating the lessons I had received earlier in the day. I used walls as my blackboard, and charcoal when I ran out of the chalk I scavenged from school. My mother didn’t like the whole setup, and the general unruliness of the kids who were my students did not help in winning her approval.

I also developed a minor compulsion for writing. I would write things down anywhere and everywhere, random things I sometimes wouldn’t even remember writing. More than once I was embarrassed when friends found my intimate ideas scribbled in my notebooks and even in the margins of my school-books. This compulsion, it turned out, didn’t even require a pen: it got so I would trace my thoughts with my finger on my thigh or in the air by my side. In Guantánamo, this drove my interrogators crazy; they did everything to stop me from writing with my finger on my body. Little did they know that most of the time I wasn’t even aware that I was doing it. I wanted to comply, but I just couldn’t. Their solution was to chain my hands tightly at my sides, making it impossible for me to write on my legs. But my finger kept moving anyway. Even if you succeed in shutting me up, I go on writing.

When I landed in GTMO, I was angry. As soon as I was told I could borrow a pen to write letters to my family, I decided to steal some of the paper and started to write my story in Arabic, mainly for myself. The pen was challenging, a highly bendable piece of plastic, more like a flimsy ink filler than a pen. Writing with it was like trying to get a straight answer out of a corrupt politician. I had to shake it over and over to keep the ink flowing, so it was both writing and a workout at the same time. I was supposed to give the pen back when I finished, but I managed to keep it hidden in my cell. I wrote letters to my family as well, but it didn’t take a genius to figure out they would never be mailed. They were just another part of the feverish intelligence-gathering campaign in the camp. I didn’t mind though. I happily obliged, drafting letters that I addressed in my mind to JTF staff members, in care of the Slahi family.

It was on Mike Block in Camp Delta that I first started writing my diaries, in Arabic, in the spring of 2003. I kept the pages hidden inside a library book, but they were confiscated when I was moved in June 2003 to total isolation in India Block. And it wasn’t just my diaries. I had also been writing out English lessons for myself, copying down things I heard from my English-speaking co-detainees and that I read in books, along with Arabic poems I remembered and little interesting bits of general knowledge. These, too, were taken. For about five months, I was allowed no paper or pen at all, and then only when Mr. X gave me his pen to write “my story” for him, or to write false confessions for my interrogators. By the time the beginning pages of my diary and my other notes were finally returned to me, I had lived through many new chapters of abuse, but I could not pick up the thread. What I had been trying to write about my captivity was not meant for the intelligence community, but rather as a kind of self-advocacy addressed to readers outside of Guantánamo. Now I knew for sure that anything I wrote would only reach my interrogators, and what happens in GTMO stays in GTMO, absolutely. Even with my chains off, my hands remained shackled to my sides.

In 2004, three years after Guantánamo opened, the U.S. Supreme Court finally decided a question whose answer should have been obvious from the start: that GTMO prisoners must have some way to challenge the government’s claims that they are dangerous terrorists. The government’s first solution was to create the so-called Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRTs), where prisoners could finally contest their designation as “enemy combatants.” I had never been an enemy of, or fought against, the United States, and I liked my chances when I first heard I would have a CSRT hearing. But that little rush of optimism faded when the serviceman who was to be my “personal representative” for the hearing came to see me in an empty building in Echo Special, accompanied by the woman who was my lead interrogator in the final pages of this book, a military intelligence noncommissioned officer who called herself Amy.

The PR was a young white Air Force captain in his midthirties. He was quiet, almost disinterested, and straight to the point. His demeanor spoke volumes about the kind of process that awaited me—he obviously didn’t think it was going anywhere. Most of the meeting concentrated on establishing the fact that he wasn’t on my side. The PR was supposed to be acting as my lawyer, in effect, but he explained that the board could pick and choose the information they would share even with him about my case. And then he informed me that he could share anything I might tell him in private with the board if he thought it had important intelligence value. Meanwhile, Amy seemed to be the one with a plan. She was encouraging me to admit to anything the board would throw at me, suggesting that this would make my life easier.

But for some reason I rebelled against the idea that I should throw in the towel. I found that somewhere, deep down, the hope of getting my freedom back had never left me. I could see the process was only for show, but I thought even if my PR and interrogator weren’t as zealous as one might hope, the officers on the bench might still listen and surprise everyone. I just couldn’t believe that a democratic government with more than two hundred years of experience in upholding the rule of law could really rig trials, with everyone on board.

I asked to confer with Amy. The captain thought I was an idiot. How could I seek advice from someone who wanted me locked up as long as possible, an interrogator whose job depended on keeping me in custody? But I wanted to put her on the spot; after all, she knew by then that I hadn’t done anything against her country. I asked her to repeat for me the kinds of things that I should say at the hearing.

“I’m not a lawyer,” she said, sweating.

The hearing started badly. I was so nervous I even made the comedy-routine mistake during the swearing in of repeating “I,” then “State your name.” Everyone in the room was laughing. From then on, though, I just tried to listen to the allegations and debunk them, one by one. Because detainees weren’t allowed to attend tribunal sessions where the so-called secret evidence was presented—how something can be “secret” and “evident” at the same time I still don’t understand—it felt as though I was defending myself against an invisible army of attorneys. But a member of the tribunal had asked Amy to leave the room during the proceedings, which I took as permission not to follow her instructions, and soon I was just concentrating on presenting the facts of my life as clearly and plainly as I could, in my rather poor English.

The result of the CSRT hearing was no shock; just about everyone got a negative result. But I was emboldened. Defending myself hadn’t hurt me. It was clear that Amy had access to the transcript afterward, but she never scolded me. And more important, some of my guards openly supported me. One of my escort guards, a corporal everyone called “Marine,” was making fun of the allegations after the tribunal, and he and a colleague I knew as “Big G” told me I won the argument in the CSRT. I gained credibility among the guards as an innocent man. I was recovering my voice. I began to think again about my story reaching someone outside of Guantánamo.

That opportunity came thanks to the landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in favor of the British citizen Shafiq Rasul, in which the court first ruled GTMO detainees can challenge their detention in habeas corpus proceedings in courts in the United States. Finally, we would be able to present our cases and be judged by Americans who were not in the military or intelligence services.

My first meeting with my attorneys was in mid-June 2005. I prepared for it by writing a summary for them of the full story of my detentions. One of the guards gave me a green spiral notebook that I used for that purpose, filling it with dates, names, and detailed notes about my life and five years’ worth of interrogations. I handed it to Nancy Hollander and Sylvia Royce at our meeting. I consider myself very lucky: detainees had no choice in who their lawyers would be, and for some it took years to build trust with their attorneys. But I could tell right away that my team would listen to me. They took the notebook with them and asked me to write more.

I began again, this time writing the full narrative. To ensure my manuscript would not be seized or destroyed, I wrote it in chunks, as a series of letters to my lawyers. This meant what I wrote became protected attorney-client material that my interrogators couldn’t read. I would finish a section, ask for an envelope, wrap the papers as tightly as I could and send them off. The letter would be delivered to a secure facility just outside Washington, D.C., where all GTMO’s protected attorney-client materials are held. I wrote day and night in the isolation hut that I shared with my guard team in Camp Echo, bombarding my lawyers with writing.

I knew my story, but I didn’t know all the words to express it. So I often sat with my guards, playing cards or drinking tea and writing at the same time. If I got stuck on a word or an expression, I’d simply ask them.

“How do you say in English that someone suddenly starts to cry loudly?”

“Burst into tears,” a guard who was a Navy petty officer told me.

“What do you call the person who speaks on the radio?” I asked. I was remembering the woman I heard on the radio when I was being transported from the Amman airport to the Jordanian intelligence prison. I could hear her sleepy voice through my earmuffs; she kept interrupting the wonderful music with comments about the day’s weather. When the Jordanian rendition team realized I could hear the radio, they jumped to turn it off and played a tape instead.

“Presenter?” one would say.

“I don’t know. When they play music?”

“DJ?” one would volunteer.

“What do you call the things they put on your ears?”

“Earmuffs?”

“When you cook, when you put something on your hands to protect them from the heat?”

“Mittens?”

“Oh, yeah!”

I wrote section after section, keeping track of page numbering so that my attorneys could assemble the whole manuscript in the secret facility. I had in my head everything I wanted to write: just the truth as I remembered it, without embellishing. I came to understand that you can convey everything in your head in any language, as long as you have the will and people around you who speak the language, and you are not afraid to ask questions or make mistakes. I wrote until I was finished, and on September 28, 2005, I simply wrote, “The End.”

When I began those pages, I thought I was writing for my lawyers, so they could know my story and defend me properly. But I soon saw I was writing for different readers, ones who could never set foot in Guantánamo. For way too many years, the U.S. government had shut me up and done the talking for both of us. It told the public false stories connecting me to terrorist plots, and it kept the public from hearing anything from me about my life and how I had been treated. Writing became my way of fighting the U.S. government’s narrative. I considered humanity my jury; I wanted to bring my case directly to the people and take my chances. I wasn’t sure if the pages I wrote and gave to my lawyers would ever become a book. But I believed in books, and in the people who read them; I always had, since I held my first book as a child. I thought of what it would mean if someone outside that prison was holding a book I had written.

Nine years would pass before that happened. But just writing those pages empowered me. Now when Amy encouraged me to report my mistreatment, I agreed. She notified her boss, a Marine lieutenant colonel named Forest. They sat with me and questioned me about my yearlong, secret “Special Projects” interrogation and told me they were filing formal reports. Late in 2005, when I appeared again before another board assigned to review our cases, I felt safe and confident enough to tell the board many of the things I had written in the manuscript and reported to Amy. It’s strange to me today to realize that in those days I may actually have been more interested in getting my story out than in getting out of GTMO. I told the board I had written a book about everything I was telling them, suggesting they should read it. They listened to me for hours, asking many questions. Only at the end of the session did I learn that the board had no power to decide my case. And still later, when my lawyers were allowed to get a transcript of this Administrative Review Board hearing, we discovered that much of what I had told them about the mistreatment was missing. Exactly when I started to describe the worst abuses, the government claimed, the recording equipment “malfunctioned.”

Any hope for justice from the GTMO system faded again, and I again doubted whether my story would ever get past the U.S. government censors. But my lawyers kept working. Because my manuscript had been sent confidentially to them, the power to clear it for public release rested with the so-called Privilege Team, a group of mostly retired intelligence officers and government employees who were granted access to view correspondence between lawyers and detainees. But the Privilege Team refused to clear the letters that made up the manuscript. Instead, it suggested that my lawyers send everything back to me in GTMO and have me try to send it to them through regular mail. I had learned from trying to send letters to my family that putting something in the mail was about as effective as throwing it away, or at least sealing it inside a time capsule. And we knew that, like those letters, anything I tried sending through regular mail would be open to the U.S. government to read and to use against me in any way it chose.

My lawyers filed secret motions in the court in Washington, D.C., to force the Privilege Team to clear the manuscript for release. Everything happened behind closed doors between my lawyers, the government’s representatives, and the judge. I was not allowed to attend these sessions, or even know what was being said about my manuscript. The litigation dragged on over five years, and in the end came to nothing. My lawyers could not even tell me why the Privilege Team was insisting it could not clear the manuscript or why, in the end, our motions failed.

So my lawyers and I decided to do what the Privilege Team suggested: send the manuscript back to GTMO and give up the attorney-client privilege. Now my writings were open to the government to use against me in my own habeas corpus case and in any proceedings it might decide to bring against me. But that still was not enough for the U.S. government. The government officially declassified the manuscript, but continued to call it “protected,” meaning it was still classified in effect, and could not be publicly released. Our frustration continued: we had not been fighting all those years so the government could tell my lawyers, “Now just you and your lawyer friends can read the manuscript.” My lawyers prepared to take this to the secret court again. Finally, the government decided not just to declassify but to “unprotect” the manuscript—a process that included adding all the redactions it considered necessary for it to be publicly released.

This whole process took almost seven years.

I remained for all that time in my isolation hut in Camp Echo Special. There were times when my faith that I would someday be released was severely tested. In late 2006 or early 2007, two FBI agents from Minnesota came to visit me and ask me about a young Arab man whom I was told was from Minneapolis. I could not possibly have known him, and everything I thought I knew about that part of the world came from a Chris Rock standup routine. According to him, no African Americans live in Minnesota, and so, by way of extrapolation, I had concluded that there must not be any Arabs or Arab Americans in Minnesota, either. But apparently I was wrong. The two men spent hours grilling me about this young man. In the end, they pulled one of my interrogators aside and told him that the way I talked to them meant I would never leave GTMO, or so my interrogator told me after they left the base. It was one of many, many days when I felt that I would never see freedom.

But there were some very hopeful days, too. One was in January 2009, the day after President Obama’s inauguration, when he signed the executive order to close Guantánamo. I don’t know how the outside world received this news, but in GTMO everyone took it very seriously. The Joint Task Force gave each detainee a copy of the President’s order. Very high-ranking officers toured the camp and spoke with many detainees. An Air Force captain in his jumpsuit and a four-star Navy admiral actually sat and talked to me. With them were several JTF staff members, including Paul Rester, GTMO’s director of intelligence. This delegation wanted to make sure inhumane practices were no longer on the menu at the camp.

I was elated. I cleaned the whole compound and took extra care of my garden. One of my guards was telling me not to bother, since I was going home. But remembering the history of Guantánamo, and thinking it might once again be used for refugees, I wanted the camp to look as good as possible for those who might be sent there after me. Everybody in GTMO—detainees, interrogators, and guards alike—truly believed that Obama would make good on his promise to close the place. We knew some of the detainees were going to be transferred to the United States for trial, but by then everyone knew that I had done nothing, so I was sure that this would not be me. Paul Rester even told me that I was going to be released, to Belgium or to Germany, he predicted.

That did not happen. But that same year my habeas corpus case was heard by District Court Judge James Robertson in Washington, D.C. A little over a year after Obama’s promise, Judge Robertson issued his decision, which ended, “The petition for habeas corpus is granted. Salahi must be released from custody. It is SO ORDERED.” Again I briefly believed I would be going home. And then I learned that the Obama administration was appealing several habeas corpus decisions, including mine, and I knew once again I wasn’t going anywhere. But in preparing for the habeas corpus case, I learned how much information the U.S. government itself had released about my treatment in GTMO, and Judge Robertson’s opinion showed the world that the government’s version of who I was and what I had supposedly done was not true. It had become impossible for the government to argue that my own version of my story must stay classified.

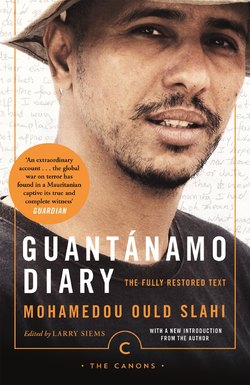

When my lawyers finally received the censored public version of my manuscript, they contacted Larry Siems, and he chose some excerpts and wrote about my ordeal for Slate magazine. I was shaken when I learned that parts of the manuscript were now in print. I was dying to read it, but it had been eight years since I had seen any part of it, and I didn’t want to wake up memories I had been doing everything to forget. I was also afraid that I would embarrass myself with my unpolished English. But my fears soon faded. Of course there were painful moments in the excerpts; I read them like the wide-awake sleeping wolf in the Arabic proverb, with one eye open and one eye shut. But I also found myself reliving scenes that made me laugh.

And then, at long last, I saw my book . . . on TV.

It was January 20, 2015, a Tuesday, around 10 a.m. I was having a Spanish class with an Egyptian American JTF contractor who calls himself Ahmed—a random pseudonym, because contractors weren’t allowed to share their names with the detainees. Ahmed’s Spanish, as he had confessed to me, was extremely basic, but I welcomed any opportunity GTMO offered to learn languages, in casual conversations or classes. Since I was his only student, our class took place in my cell. That morning, I turned the TV on to make a little more noise and give some life to the class, and both of us froze: the Russian channel I had tuned into, RT, was running a long piece on my book, including a live interview with Nancy Hollander and Larry Siems in RT’s London studio. At one point, my picture filled the screen.

“You know this guy?” said Ahmed, joking.

For the first time, I felt what it’s like to be free inside a prison, that moment of total freedom that comes when you take back some of your lost dignity. I thought of Tim Robbins in The Shawshank Redemption, and the smile on his face when he offers his fellow prisoners drinks, the drinks he earned for doing his guards’ tax returns. My cell expanded, the lights became brighter, colors more colorful, the sun shone warmer and gentler, and everyone around me looked friendlier; even the small, short-haired female sergeant who seemed to be on an open-ended fast from smiling smiled that day, not once but many times. Now my family and the whole world would know my side of the story. That was liberation.

About fourteen months after Guantánamo Diary was published, I learned that I was scheduled for a hearing before the Periodic Review Board (PRB). President Obama set up the review boards in 2011, but it took years for them to get going, and when they did, I watched for months as other detainees had their hearings. It seemed like no one wanted to touch my file. Finally, in the summer of 2016, almost fourteen years after I was brought to GTMO and six months before President Obama’s second term would end, I would have my chance to be cleared for release.

As with earlier versions of review boards, I was assigned personal representatives. This time, though, the PRs really seemed to have the interests of the men they represented at heart. When I first met with my PRs, a Navy commander and an Air Force lieutenant colonel, they expressed frustration that some of the other detainees had hurt their chances during the PRB hearing because they were too thirsty to tell their stories. In fact, they explained, the Periodic Review Board was not a forum for detainees to tell their stories. This was not a court that was supposed to decide facts about the past; instead, like a parole board, the review board was supposed to weigh whether the detainee would presently pose a threat to the United States if he was released.

But when they were preparing for their hearings, my PRs told me, many of the men would write. A lot. They kept writing and writing, I’m so and so, and I went to so and so, and I did this and this, and I’m a good man, trying to tell their whole story. Their representatives would give their papers back to them and tell them, “We can’t say this in the hearing. This hearing is very limited, very formal.” But the detainees insisted. “No, it’s my life, it’s my decision, I want to say this.” It is the burning desire of an innocent man: I want to register an injustice, I want the world to know I did nothing wrong, I am not a bad person. Some had lost their hearings because of this basic need.

The personal representatives told me this, and I was smiling. “You won’t have this problem with me,” I told them. I’ve already told my story, I was thinking. I’m past that. I’d had my closure. The world had my versions of events, and I was happy.

3.

But my book, as it was originally published, was broken goods.

The first I saw of the published version was a few months after publication day, when Nancy Hollander brought me a photocopy my publisher had made. She could not bring me the actual published book, because the U.S. government would not allow me to see the introduction and footnotes that Larry Siems had contributed, on the grounds that they sometimes referred to documents the government still called “Classified”—even though those documents can easily be found online. The photocopy was just my text, with all the government’s redactions.

As I read through the text, my mind automatically filled in what was missing; it took me a while to realize that what I was reading and what my readers were seeing were often two different things. It wasn’t just that the readers were without certain details or information. It was that they would have in their minds the idea that what was missing was something that the U.S. government considered threatening.

To be honest, I do not know why many of the things I wrote were censored, and I cannot follow the logic of many of the redactions. Why on earth would the U.S. government censor a poem I wrote for my interrogator as a parody of a well-known literary classic? Why would it censor the fake names that a group of my guards gave themselves when they decided to take on the roles of characters from Star Wars? Why would it censor the names of people I was being questioned about during interrogations, when it did everything it could to link me publicly to these same people? All of this supposedly had something to do with “national security,” but I wasn’t convinced. I had been delivered to Jordan, then to Bagram, then to Guantánamo because of “national security.” I was abused in Jordan and Bagram and tortured in GTMO because of “national security.” And I would always think, Could we be a little more specific about what we mean by “national security”?

I grew up under a military dictatorship, not as brutal as some, but undemocratic nonetheless. I remember my mother telling my older brothers not to discuss politics, for fear the walls would hear. In my country, we’re used to censorship in the name of national security. What shocks people here in Mauritania is that the censorship in Guantánamo Diary isn’t just in the Arabic edition; it comes directly from the American original, which means the information is being kept from the American people.

I wonder what would America’s founders think of this censorship. I like to think it’s the same thing they would think of my entire story: after all, one of the complaints against the British king listed in their Declaration of Independence was “for transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences.” I like to believe they would have been on my side in a discussion in Guantánamo I remember with an FBI agent named William. He was explaining my legal situation to me, and how I couldn’t be treated as a U.S. citizen. Understood, I said, but how can I be without protection from anywhere? Of course I was protected—by U.S. law, as American courts would later confirm, but also by the laws of Mauritania, where I was born, and by international law, because the rights the United States was violating were not just American rights, but human rights. But this was something William would not or could not see.

When I was young, I memorized a poem by the Iraqi poet Ahmed Matar called “Prison Guard.” It begins,

I stood in my cell

Wondering about my situation

Am I the prisoner, or is that guard standing nearby?

Between me and him stood a wall

In the wall, there was a hole

Through which I see light, and he sees darkness

Just like me he has a wife, kids, a house

Just like me he came here on orders from above

I wasn’t exactly enlightened all of my time in Guantánamo. I was often confused and angry, and still young in my thinking. But I think it was easier for me to see the people who were guarding and interrogating me than it was for them to see me.

In the summer of 2003, after a very long day of abuse that was part of my “Special Projects” interrogation, a female sergeant bragged to me about how knowledgeable Americans are in sexual matters, and how backward “Yemenis” like me are in that department. Nothing in that long day of torments hurt me more than to be confused with someone from Yemen. I admire the Yemeni people enormously; they represent all that is decent and honorable, in my experience. But here I was, being tortured slowly, and the woman on whom the job fell that day did not even know who I was. Not even close. If she had said Moroccan, Algerian, Malian, Senegalese, even Tunisian, I could maybe understand the geographical confusion. But Sanaa is four thousand miles and a continent away from Nouakchott.

I was shocked and hurt by her ignorance, but in a way she wasn’t too far off when she threw the Yemenis and me in the same pot. In Guantánamo it mattered where you were from, and early on detainees were divided into those with some entity backing them, usually an important American ally country, and those without. Those who remained in GTMO the longest were almost all from the latter group. Our individuality didn’t matter as much as the fact that we were poor and from countries that lacked the political will to stand up for us and demand our release.

The interrogator who said this to me appears twice in Guantánamo Diary—or I should say “appears,” because the U.S. government blacked out both passages so she is very difficult to see. Readers can’t see any of her features; they can’t even see that I refer to her as “she.” I did not use her name because she did not bother even to make up a name for me. In the United States, if the FBI or the police show up on your doorstep, they say my name is so-and-so, and show you their identification. The same is true for the police and intelligence services in Mauritania, Germany, and Canada. One of the aspects of Guantánamo that I found most disrespectful and insolent to us as human beings was the way they came to us nameless, sometimes even faceless, and said, “I’m here to interrogate you and ask you questions and you don’t know who I am. I can do anything to you without your being able to identify me.” They were so busy hiding themselves they couldn’t see the most basic things about the men that they were questioning.

Writing the manuscript for Guantánamo Diary was in a way a reaction to this. I first and foremost wanted to tell my side of the story, to say, “What those people are saying about me is not correct, it’s wrong, and here I am: Come and test me, ask me any questions yourself. When I was nineteen and twenty I went to Afghanistan for a couple of months. That’s it. I came back. I’m not a killer. I’m not a bloodthirsty person. I’m very peaceful. I love people. This is who I am.” But I also meant my story to be breaking news. I wanted the world to know what was happening in Guantánamo. For over seven years, the U.S. government kept that breaking news under lock and key, until it was not news anymore. And then it still said it could be released only in censored, broken form.

I will be forever grateful to my publishers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and around the world who were kind enough to publish these broken goods, and so very, very grateful to all who read the book in its broken form. I owe my freedom to my attorneys, who wrestled my manuscript into the light, and to all of you for sharing and reading it. And I believe I owe us all this repaired version. I never meant my story to be blacked out and redacted, and since I returned home, every person I have spoken with who read this book has asked me if she or he will now be able to read it in an uncensored version.

I tried to do this in the most direct, correct way, by asking the U.S. government to give me back my original, uncensored manuscript. The government refused repeatedly, and so I have worked with my editor Larry Siems on what we came to call this “repair,” because it often felt like we were trying to restore a very ancient building.

I thought at first this would be easy, a matter of reinstalling missing bricks to their proper places. I did a small section, and because the redactions were all little bricks of fact—names, places, sometimes dates—they slipped right in. But things quickly became complicated when it wasn’t just a few words that were missing, but sentences and paragraphs, full pages even. I began with the obsession of replacing what was taken out brick for brick, tit for tat, as a kind of revenge for the censorship. But revenge is always problematic—it ends up imprisoning you. In the longer censored passages, I knew the action that was being described, but not the phrasing or the order of the sentences, or even the exact aspects of the person or the experience I had described.

I worked in a copy of the book, making notes above the redactions and in the margins, and then I would take a break, go home, eat lunch, and remember even more. I found myself writing and remembering, beyond the boundaries of what I was supposed to be filling in. But it was by doing this, and not trying to confine myself to the government’s prescribed blacked-out spaces, that I felt myself recovering the feeling of the original pages. And then Larry and I did what we were denied the opportunity to do the first time Guantánamo Diary was published: we worked together to edit these censored sections.

The result, like the original uncensored manuscript, is as close as I can come to the truth as I experienced it and understand it, in the best form I can express it.

I am publishing this new, repaired edition in the same spirit in which I sent a censored version that I had not even been allowed to see into the world in 2015. This is especially true with respect to the men and women I have described in these pages. Except for senior officials who have been named publicly in U.S. government reports or the press, I have chosen in this restored edition to refer to my captors, interrogators, and guards with the names and nicknames I knew them by in prison. To all of them, I wish to renew the invitation that I delivered through my attorneys in my Author’s Note for the first, censored edition. In that Note, I said that I bear no grudge against anyone for my ordeal and treatment, and I invited all of the women and men who appear in the book to read it and correct any errors. I said that I dreamed of one day sitting down with all of them for a cup of tea, having learned so much from one another. I mean this still, and most sincerely, as every day teaches me even more about forgiveness.

Repairing this broken text has been about seeing things that someone wanted hidden. Sometimes that someone was me. When I received the photocopy of my book in Guantánamo I stayed up all night reading it, afraid that I wrote something I would regret. And yes, there were things that embarrassed me. I was especially ashamed of my habit, when I was young, of making up sarcastic nicknames for people I met. The Jordanian intelligence agent who oversaw my rendition operation was not “Satan”; he is a human being, as Ahmed Matar pointed out, with a full life and a family. That kind of name-calling is someone I was, not someone I am now. In that sense, reading what I’d written ten years before really was like reading an old diary. Sometimes I laughed, and sometimes I got very upset. But mostly I just smiled at my own silliness and learned more about who I was, and also who I am. Seeing myself this way gives me confidence for the future.

I am thankful for this confidence most of all. It comes from all the characters portrayed here, mainly government employees from around the world, whose human actions were the raw material for this book, and whose complicated humanity challenged me to be truthful, above all with myself.

It comes from everyone who helped in bringing my diaries to light, because without them there would be no book at all, and I would probably still be shouting in the dark: from Nancy Hollander and Theresa Duncan, who fought for nearly eight years to get the approval for a redacted version of my manuscript to be released; from my editor Larry Siems, who worked through the maze of that manuscript and found the book I hoped it would be; and from Rachel Vogel, Geoff Shandler, Asya Muchnick, Jamie Byng, and all those who published and promoted Guantánamo Diary around the world.

And it comes from my heroes, my readers, who in my darkest hours I dreamed were out there and who inspired and encouraged me from the start. This new edition is for you.