Читать книгу Cruel City - Mongo Beti - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

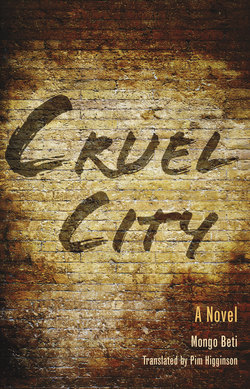

ОглавлениеCollected here are two of the most important works of Francophone African literature, finally available in English: the critical essay “Romancing Africa” (“Afrique noire, littérature rose,” 1955), and the novel Cruel City (Ville cruelle, 1954), both by the Cameroonian man of letters Alexandre Biyidi Awala, whom the world would come to know as Mongo Beti (1932–2001). Beti was born in the Northern Cameroonian town of Akométan near Mbalmayo, a city whose river and old reinforced concrete bridge can easily be imagined as models for Tanga. Indeed, numerous biographical details match up well with the novel, such as the early death of Beti’s father and the discussions the author had with his mother about religion and politics. The big difference of course lies in the character’s relative illiteracy. Over the course of his nearly fifty-year career, Beti would receive broad acclaim as one of the greatest literary tellers of political and existential truths; he spent decades in exile for his criticism of Cameroon’s post-independence regimes, and his writing would, on occasion, even be censored in France. Both on their own and taken as the beginning of this substantial literary production, “Romancing Africa” and Cruel City represent a pivotal moment for the continent: the first drafts of a Francophone African literary canon.

“Romancing Africa” was published in the celebrated Paris-based journal Présence Africaine.1 The young author’s essay is a single-minded manifesto: a programmatic and radical break with the past; a bold challenge to colonialism and its various avatars; and a call to literary arms. Beti’s first anti-establishment attack forcefully announces—demands, in fact—a path forward, toward a postcolonial African literary production. Along with its sheer brashness and daring, this youthful text also enumerates the challenges facing the sub-Saharan African novelist working in French. In summarizing these challenges, “Romancing Africa” first posits the total absence of quality literature in or on Africa, by which it means books that are actually read. By the essay’s own account, this initial criterion immediately creates a series of problems. First, given the historical, economic, and cultural effects of colonialism, there is no African reader-ship; only the French will consume such works. This French (bourgeois) readership thus single-handedly determines literary success; France controls the means of publication, distribution, and by extension, the terms of consumption.

According to Beti, the French reader in turn expects two things: that writing on Africa(ns) stress the folkloric; and that the colonial enterprise be celebrated, or at the very least not criticized. This latter expectation comes into immediate conflict with Beti’s second determining criterion for a quality literary work, besides its popularity: that it objectively—that is to say critically—represent the effects of colonialism. Intervening literary history has thereby revealed Beti’s two conditions for a quality African novel in French to be mutually exclusive. Indeed, any novelist wishing for success on the French literary scene will, according to Beti, avoid like the plague the truth of African modernity (its cities, its multiple engagements with global capital, its repressive administration, etc.); this author will necessarily dodge the complex and violent legacies of colonialism. Such a book, according to Beti, while popular, won’t be a quality work of fiction because it won’t be realistic, won’t be honest about its subject matter. Significantly, this tension that Beti raised so succinctly almost sixty years ago remains in various forms at the heart of most African writing today, and certainly informs and shapes critical debates.

Of course, having established the essay’s argument, how does “Romancing Africa” explain the author’s own fiction? Or in other words, does Beti’s text reach the author’s own standards of excellence? If we hold him strictly to the very first rule, namely that the work should sell, the answer would have to be no. Despite its importance to the Franco-phone African canon, Cruel City has been through only three small printings in French. Regarding the second criterion, does Cruel City escape the fundamentally testimonial—what Beti calls the picturesque—expectations of a French reader-ship? This is far more difficult to assess; rather, this question highlights Beti’s ambivalence about where his character— indeed the African novel as whole—should go. “Romancing Africa” objects most strenuously to the representation of Africa as folkloric atemporal space; in this sense, to a Hegelian “timeless Dark Continent” Beti’s novel opposes the historical present of a land coming to grips with its modernity, that is, with the colonial experience itself. What confuses matters is that the central protagonist, Banda, ultimately never makes the transition to the city; he remains caught in the maternal space of tradition that Odilia clearly represents. At the end of the novel, Banda knows he must listen to the one voice he trusts, namely his own, but can’t quite yet bring himself to make the move . . .

While the relationship between the two texts is subject to interpretation, what we can infer from “Romancing Africa” is that Cruel City is experimental; the novel formulates its own conditions of possibility as it unfolds. As Banda makes his way from the countryside of Bamila to the city, Tanga, we witness the Francophone African novel transitioning to a new form. Not surprisingly, catching this movement challenges the process of translation, since questions concerning language lie at the heart of any manner of narrative exploration, and Cruel City is of course no exception. Because it is a series of experiments, the novel can appear—or is—flawed: it drifts through phases of sentimentalism and is repetitive in parts. As I mentioned above, perhaps the story’s most significant flaw is the absence of a convincing resolution. In sum, as its critics have often pointed out, this is not a mature work of fiction. At the same time, any heavy-handedness is the trace of the Promethean task the narrative performs; these faults are the immediate effect of the canon formation in which the novel is involved.

The novel’s flaws resulting from its grand ambitions can be baffling for the translator; there are times when certain turns of phrase had to be modified, “corrected,” or otherwise rendered more readable. At times I made such translational editing changes, but only with extreme caution and in highly selective cases since, taken as a whole, these shortcomings—if indeed they are such—are also precisely among the text’s most interesting features. Beti’s novel is a laboratory where modern Francophone African fiction is being deliberately wrought, almost out of thin air. The twist and turns of plot, the rhythm of the prose, all of which I have tried to reproduce in the English, constitute a series of trials (and errors) that explore the issues raised in “Romancing Africa.” Ultimately, whether or not Beti succeeds is almost irrelevant: the novel is its own justification. In sum, “Romancing Africa” and Cruel City represent the theoretical and practical inauguration of an absolutely new kind of Francophone writing.

PIM HIGGINSON

NOTES

1. The journal, launched in 1947 by Alioune Diop, had heavy support from a number of famous French and African diasporic intellectuals, such as Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, Richard Wright, Michel Leiris, and Jean-Paul Sartre, whose names would also appear prominently in its pages. It should be noted that Beti subsequently became disenchanted with what he saw as its over-coziness with French interests on the African continent.