Читать книгу The Book of Awesome Black Americans - Monique Jones - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Making Boss Moves

Much of Black America’s history was affected by the country’s human rights abuses. Clearly, America has not been particularly kind to the Black American. However, even with an entire country set against them, the Africans who were brought to the West as slaves still fought for a better life and many actually achieved it in many disciplines, including business. In the eighteenth and (part of) the nineteenth centuries, it would have been impossible for many to believe that Black men and women could own businesses, employ hundreds or even thousands, and invent some of the most important products America has ever seen.

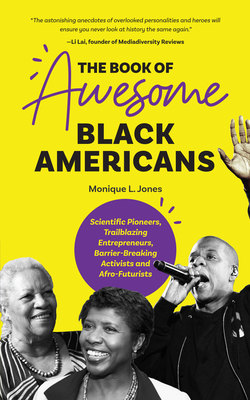

As a person living in the twenty-first century, it is probably impossible for you to remember a time when there weren’t Black movers and shakers in the world, building businesses, making lucrative deals, and reaching the monetary height of success. We should be thankful for that success, since it’s anecdotal proof that, despite all of the setbacks, our country has made societal progress. Today’s Black businesspeople can look like you and me, setting out into the world of entrepreneurship. Or they can look like bigwig rappers like Jay-Z and P. Diddy, two rappers who were able to transform their music careers into lucrative businesses.

Jay-Z is behind the music distribution company Tidal but has many other companies to his name, such as the urban fashion line Rocawear and the music publishing and artist management/touring company Roc Nation, and he’s part owner of the New Jersey Nets, among other ventures. Diddy, on the other hand, made his most famous business mark with his clothing line Sean John. He has since made inroads in the wine and spirits category with his deals with Diageo’s Ciroc and DeLeon tequila. He also co-owns AQUAhydrate water with Mark Wahlberg and has a stake of Revolt, a popular television network.

Today’s Black entrepreneurs and businesspeople come from all walks of life, from the wealthy to the bootstrappers. It’s great that we live in a time where we have so many examples of Black businessowners that we can be inspired to follow our dreams.

It wasn’t always this way. Many years ago, all we might have heard about were White businesspeople and their achievements, and it would have been tough to find examples of strong Black businesses unless you knew where to look. But they were out there, and they were laying the groundwork for business-minded Black Americans like Jay-Z, P. Diddy, and others to follow behind.

Early Pioneers

Black Americans have been masters at making a way out of no way and creating a decent life for themselves despite everything that was stacked against them. Some, like Benjamin Banneker, went above and beyond and showcased savant-like talents that progressed a nation, even while that same nation was trying to keep him and those like him suppressed. Banneker was born a free man in 1731 Virginia and, as such, he attended Quaker schools. Thanks to the Quaker anti-racist philosophy, he probably grew up in a blessed bubble of protection against the harsh, racist outside world. However, he left school after the second grade and was self-taught afterwards. He was apparently his best teacher, since he excelled in many areas, including engineering, astronomy, mathematics, writing and public speaking.

Banneker was easily one of the smartest people in the eighteenth century, replicating the blueprints for Washington, DC, from memory after the man hired for the job, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, left his position as engineer in a huff and took the plans with him. He also built the first clock in America, which worked perfectly for forty years. Another of his accomplishments includes his annual farmer’s almanac, which he created after becoming interested in astronomy (and successfully predicting an eclipse from his own calculations). The almanac contains information all drawn from Banneker’s mathematic and scientific know-how and became a top-selling book in several states including those in the original thirteen colonies as well as those closer to the South like Kentucky, a tremendous feat for the first book of science, and one of the first published works, written by an African American author.

Banneker’s almanac was useful for farmers of all stripes, but one of the most important uses he had for it was as a weapon against racism and war. One of his tactics included sending a copy to Thomas Jefferson, who had hired him to replicate plans for the capital. Although Jefferson’s most famous line from the Declaration of Independence was, “all men are created equal,” he wasn’t a practitioner of what he preached; he owned hundreds of slaves on his property, Monticello, and kept Sally Hemmings as what many would have called back then a “mistress,” although in reality she was a victim of his sexual abuse, since slaves didn’t have the right to consent. How can you change the mindset of a man whose own behavior is wildly hypocritical? It’s not known if Banneker thought his plan of sending his almanac was a long shot, but he sent it anyway, with the goal to impress upon Jefferson that his own words of men being created equal should stand for Black men, too. However, despite Jefferson’s words of praise, he failed to implement any action against slavery, which is why Jefferson consistently gets an L in history for being one of the country’s biggest hypocrites, a man full of flowery words but no backbone to implement them in reality.

Regardless of being unable to change Jefferson, Banneker charged forward when it came to speaking out against injustice, whether that was through his inventions or his almanac, his work as a farmer, surveyor, engineer and city planner, or through his writings as an author or his research as a mathematician and astronomer. Banneker and others like him provided inspiration for those looking to make a better life for themselves, even with slavery and discrimination staring them in the face. That drive kept up even after the Civil War, when many Black Americans were excited to start life as free Americans.

After the Civil War, America was ready for Reconstruction, which took place from 1865 to 1877. This period was supposed to establish Black Americans as independent, self-sufficient citizens. Instead, Reconstruction was a volatile time in which freed Blacks faced violent racism, often resulting in lynchings, burnings, and other fearmongering tactics. It can be argued that Reconstruction was doomed from the beginning, since President Abraham Lincoln, the architect of Reconstruction, was assassinated one week after the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery. Even though Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s Vice President, assumed Lincoln’s Reconstruction policies after he took over the presidential office, states as far up across the Mason-Dixon line as the Midwest began installing rules to limit Black economic and social progression.

It can also be argued that Reconstruction didn’t last long enough to establish any kind of nationwide social sea change. Once the initiative became dismantled via Lincoln’s assassination and Southern and Midwestern states undermining the government, the idealistic notion of Reconstruction became something like a pipe dream. However, Black Americans had survived slavery through sheer will and ingenuity—they didn’t have the support of the government when they needed it during slavery, and they weren’t going to limit themselves after slavery just because of this lack of support.

Despite states trying to limit progress, even with violent measures, Black Americans persisted throughout the trauma and established themselves as prominent business leaders, inventors and economic innovators.

Inventors and businesspeople like Banneker and others from the eighteenth century showcased the intelligence of the Black mind, one that was able to reach for the stars despite Black Americans being shackled on the ground, whether by actual shackles or the societal shackles placed on free Black people. That uplifting outlook on life can be found in the life of Clara Brown, who was a slave in Virginia before becoming a community leader and philanthropist. As a philanthropist, she helped former slaves acclimate to free life in Denver, Colorado, during the state’s Gold Rush. Brown became the first Black woman to reside in Denver after arriving in 1859, and she’s believed to be the first Black woman to take part in the Colorado Gold Rush. Brown was also a business owner, opening a laundry shop wherever she went, including in Denver.

That entrepreneurial spirit can also be found in the area of Tulsa, Oklahoma, once known as Black Wall Street. Black Wall Street was the nickname for Greenwood Avenue in the suburb of Greenwood. Greenwood Avenue was a breath of fresh air in America since it was home to hundreds of prosperous Black-owned businesses. It became a hot zone for commerce because of Tulsa’s oil boom in the early 1900s, which attracted many Black Americans from the South. It’s ironic that Oklahoma’s Jim Crow laws, which in the Southern and some Midwestern states prohibited Blacks from working, socializing, and living in general alongside Whites, helped Black Wall Street grow. Because Blacks couldn’t do business in the same areas as White Oklahomans, the isolation forced Black businesses to innovate, starting with O.W. Gurley, the entrepreneur who established Black Wall Street in 1906.

Gurley was a wealthy Black landowner who had a presidential appointment from President Grover Cleveland before he moved from Arkansas to Oklahoma to take part in 1889’s Oklahoma Land Run. When he came to Tulsa in 1906, he bought forty acres of land, which became Greenwood Avenue, named in honor of a city in Mississippi. Gurley also established Vernon AME Church, which was destroyed during the Tulsa race riots and rebuilt in 1928. More on that tragedy later.

All of the businesses were owned by Black businesspeople and catered exclusively to Black clientele. Despite Oklahoma’s systematic racism, however, both White and Black Tulsans patronized the shops and businesses in Black Wall Street.

Black Wall Street exhibited the business power of Black Americans when given the chance. The area became home to many Black multimillionaires, and, if this area was a White-owned neighborhood, Tulsa wouldn’t have had a problem. But because it was run exclusively by wealthy Black Tulsans, the White community felt threatened by their success. So, the Tulsa riots arose after a nineteen-year-old shoe shiner named Dick Rowland allegedly assaulted seventeen-year-old Sarah Page, a White elevator operator in a White-owned building. Rowland only used the elevator to get to the building’s bathroom, and Page herself never pressed charges. But with an opportunity present, armed White men rampaged Tulsa, with armed Black men rising up to protect Rowland. Today, the burning of Black Wall Street is known as domestic terrorism, but, at the time, it was seen as keeping Blacks in their place, based on the imaginary fear created by stereotypes and assumptions.

After Black Wall Street

We can be thankful that Black Wall Street wasn’t the only place where Black business excellence thrived. Throughout the country, Black inventors, businesspeople, and innovators charged forward and created unimaginable lives for themselves. One of those businesspeople include Garrett Morgan, who started out life as the son of former slaves in Kentucky but became one of America’s wealthiest men in the 1920s. As a young man, Morgan quickly used his business talents to better himself. Once he moved to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1895, he spent twelve years as a sewing machine repairman, saving enough money to start his own repair business. His one business soon turned into several businesses, including a tailoring business, a newspaper company which published the Cleveland Call, and a company that made personal grooming products. By the time 1920 rolled around, Morgan’s empire made him extremely wealthy, allowing him to pass on working opportunities to his many workers.

Several of Morgan’s inventions have helped shape America into the place it is today, such as the “safety hood” or gas mask, which he invented in 1916 after seeing firefighters struggle with smoke on the job. The device helped save a group of trapped miners who were stuck in a shaft under Lake Erie. The incident instantly made his gas mask a success, and he received orders from mine owners and fire departments throughout the US and Europe.

What’s sad is that, at first, his contribution to saving the lives of the trapped miners was written out of the official story in Southern newspapers simply because he was a Black man. Eventually, that glaring omission was addressed, but regardless of whether Southern states wanted to acknowledge a Black man’s invention, Morgan’s gas mask became a staple in the lives of American first responders and the military. The mask not only helped save lives of firefighters and miners, but a slightly revamped version of the mask was given to soldiers in World War I. Morgan also invented the zigzag stitching attachment for sewing machines, now a must-have for sewing enthusiasts to create stitching for fabrics such as stretch knits. He also created a device we see and use every day—the traffic light.

Morgan was inspired to invent traffic lights after he witnessed a crash between a car and a buggy. He saw an opportunity to create a product that could give motorists and other vehicles ease of mind when sharing the road. He received his patent in America in 1923 and later patented his invention in Canada and Britain. Eventually, the traffic light made Morgan even more money to add to his empire; he sold his patent to General Electric for forty thousand dollars. Without his invention, just think of how unsafe travel would be. Morgan died in 1963 as a wealthy businessman, a far cry from his meager beginnings on his parents’ Kentucky farm.

Annie Turnbo Malone was the woman whose work in beauty and hair care inspired Madam C.J. Walker to launch her own hair care business. Malone was born in 1869 in Metropolis, Illinois, as the tenth of eleven children. When her parents died, she lived with an older sister and went to school, although she wasn’t able to graduate due to illness. But as her hometown’s name suggests, Malone was already born super. Even though she didn’t finish school, her time in class fostered her love for chemistry, and it was this love that led her toward creating her first product—one that helped Black women straighten their hair without damaging it.

Malone kept creating more products until she had an entire line for potential customers, and to gain those customers, she moved to St. Louis and went door to door, giving women live demonstrations. She also debuted her products at the 1904 World’s Fair, one of the best ways to gain tons of publicity for a new product or service at the time. This amount of publicity gave her enough wind in her sails to launch her company, Turnbo’s Poro Company. She eventually married St. Louis school principal, Aaron E. Malone, and through her company’s success became a millionaire by the end of World War I. She used her wealth in charitable ways to help Black American organizations and philanthropic groups and established the cosmetology school Poro College in St. Louis.

Malone’s success in haircare paved the way for others, including Madam C.J. Walker. I feel we know more about Walker because of her ability to market herself as a brand alongside her business. She utilized her image as its own type of selling point, similar to how celebrities today use their status to sell products or business ventures or, for the Gen Z crowd, beauty YouTubers endear themselves to their audience by becoming an inviting personality. Her flair for the dramatic helped propel her to superstar status, but thankfully, she also used her fame to help other Black women find opportunity.

Born Sarah Breedlove, Walker was the daughter of slaves-turned-sharecroppers in Louisiana. Similar to Malone, Walker became an orphan during her childhood and lived with her older sister and worked in the cotton fields with her.

Her early life continued to be harrowing: she married at age fourteen as an escape from her sister’s abusive husband. But her husband, Moses McWilliams, died, leaving Walker a single mother to her daughter Lelia, or, as she came to be known, A’Lelia. Her second marriage to John Davis was also troubled, and the two eventually divorced. Throughout that time, though, Walker did her best to provide for her daughter by moving near her four brothers in St. Louis and earned work as a cook and laundress.

Her brothers’ profession, barbering, was a bit of foreshadowing as to what Walker’s life would become. She became devoted to Anne Turbo Malone’s “The Great Wonderful Hair Grower” product to recover from hair loss, presumably from stress. Her love for the product led her to become one of Malone’s Black saleswomen and eventually, Walker launched her own hair line with just $1.25. By this time, she had moved to Denver, Colorado, and was married once again, this time to an ad man named Charles Joseph Walker, and renamed herself “Madam C.J. Walker” to launch her line.

This third marriage didn’t last long either, but the name and her husband’s business acumen helped Walker establish her line and grow her Walker Manufacturing Company in Indianapolis, Minnesota. Like Malone, she also hired a line of Black women for her sales team and eventually employed forty thousand Black men and women throughout the US, Canada, and the Caribbean. She became a millionaire, owned a mansion in Irvington, New York, as well as several properties in Harlem, St. Louis, Chicago, and Pittsburgh and established the Negro Cosmetics Manufacturers Association, helping Black businessowners network and coalesce as a powerful business force.

One of the Black women Walker inspired was Marjorie Stewart Joyner, who was one of Madam C.J. Walker’s contemporaries and became a huge part of Walker’s business as part of her board of directors. Joyner was born in Virginia in 1896, and her family moved to Chicago as part of the Great Migration north for jobs and opportunities. She met her future husband, Robert Joyner, who was studying podiatry. While he was in school, she went to the A.B. Molar Beauty School and became the school’s first Black graduate. Afterwards, she opened her beauty salon, where she became known for her prowess at setting Marcel waves, a popular style at the time. It so happened that when she tried to set her mother-in-law’s hair, she failed, which prompted her mother-in-law to pay for her to attend classes to learn how to work on Black people’s hair. As it turns out, that class was taught by Walker, and she was so impressed with Joyner that she offered her a job. Even though Joyner turned her down because of her new marriage, the two stayed in contact and, eventually, Joyner became one of Walker’s demonstrators who traveled throughout the nation teaching others Walker’s famous hair tips.

Joyner’s own history with the Marcel wave led her to create a new invention—the waving machine, which can set an entire head of hair at the same time. She applied for her patent in 1928 and the machine took off. She never made a dime from her invention, since the patents belonged to Walker’s company where Joyner was still an employee, but her career in hair launched her higher up the ladder: she eventually became the vice president of one of Walker’s salon divisions and joined the board of directors. Joyner’s presence in American society is even more cemented in her philanthropy work, including cofounding Florida’s Bethune-Cookman College with Mary McLeod Bethune. It was at the college that she earned a BS in psychology in 1973. Joyner died at 1994 at the age of ninety-eight, but the spirit of her invention lives on in today’s contemporary wavers. Today’s wavers are handheld instead of looking like the intimidating apparatus Joyner invented, which was basically a hair dryer connected to several curling rods. Several handheld devices on the market today have the same multi-rod design embedded within their DNA, meaning that Joyner’s unique invention has lasting merit.

Maggie L. Walker became the first Black woman in America to found a bank, a feat that is impressive to this day, since Kiko Davis is currently the only Black woman today who owns a bank. Born in Virginia after the Civil War, Maggie began her life of service to the community by joining the Independent Order of St. Luke, which helped the infirm and elderly and promoted humanitarian causes. She served as the Order’s Right Worthy Grand Secretary from 1899 until her death in 1934.

Her banking career began in 1902 when she established the newspaper The St. Luke Herald, which helped the Order communicate with the public, and the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in 1903 to help the people utilize their own money to help themselves. She served as the bank’s president from the outset and later became chairwoman of the board when the bank merged with two other banks to become The Consolidated Bank and Trust Company. The bank was the oldest continually Black-operated bank in America until 2009.

It’s unfortunate that Walker’s achievement stands as a rarity in America today; Davis, currently the only woman who holds the same title Walker held decades ago, is the current owner of the tenth largest African American owned bank in the nation, First Independence Bank. Her ownership comes through being the trustee of the Donald Davis Living Trust, the majority stockholder of the bank. Even though the statistic of Black women in bank ownership remains unfortunately low, Davis and Walker show that it is possible for women to achieve anything they set their minds to.

Bridget “Biddy” Mason was born as a slave in Mississippi in 1818, but little did anyone know that she would grow up to become one of the first prominent citizens and landowners in Los Angeles. Throughout her turbulent early life, which included being uprooted several times to live in Georgia and South Carolina with other slaveowners before being returned to Mississippi to become the slave of Robert Marion Smith. As a Mormon, Smith moved his family and slaves to establish a Mormon community in what was then Mexican territory. That community would become Salt Lake City, Utah.

Mason’s turbulent life also included meeting free Black couple Charles H. and Elizabeth Flake, who told her to legally fight her slave status once she and her slaveowner reached California, where Smith wanted to move to despite California’s laws against slavery. After spending five years in California as a slave, she did legally challenge Smith for her freedom, which she earned via the court. She eventually became a midwife and a nurse and used her earnings to buy land in what is now downtown Los Angeles. She also established Los Angeles’s First AME Church, the city’s oldest Black church. Her wealth, which she used for charitable endeavors and for establishing an elementary school for Black children and a traveler’s aid center, was estimated at three million dollars. Mason died in 1891.

Mary Ellen Pleasant was an abolitionist who helped slaves escape with the Underground Railroad, helped finance John Brown’s failed slave uprising, and sued San Francisco for Black Americans’ right to use streetcars. Pleasant spent her childhood in Philadelphia and worked with the Hussey family in their store. After her service to the Hussey family ended in her twenties, she became a tailor’s assistant and a church organist. It was during that time that she met her first husband, James. W. Smith, a rich plantation owner with African ancestry from his Cuban heritage. Smith had gone through his own journey before he met Pleasant; by the time they finally met, he had pledged himself to the abolitionist movement.

Interestingly enough, both Pleasant and Smith were able to pass for White people, which they used to their advantage. However, Pleasant knew very well how her bread was buttered. She might have utilized her privilege to advance in the corporate world, but she used her earnings to advance the cause of civil rights. For instance, during her first marriage, she became friends with abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, the latter of whom promised her his estate if she kept fighting for the end of slavery. Pleasant and Smith also were a part of the Underground Railroad, helping slaves escape to Canada.

Pleasant eventually remarried, this time to JJ Pleasant, a shipboard cook who decided to try his luck in the California Gold Rush. Pleasant followed him with the hopes of running a boarding house and restaurant. Her restaurant, which became known as “Black City Hall,” was where Black Americans who arrived in San Francisco after slavery could find work. She later invested in a boarding house for wealthy businessmen in the area as well as a Sonoma Valley ranch that included a vineyard and horse-racing track.

When most people think of the lightbulb, they think of Thomas Edison, but the story of the lightbulb continues with Lewis Latimer, the son of runaway slaves who grew up to work at a patent law firm after his stint in the Navy during the Civil War. It was during his time with inventor Hiram Maxim at the US Electric Lighting Company that he patented the carbon filament for the incandescent lightbulb. This small invention made lightbulbs more affordable and accessible for families, which made electricity more accessible for all. Latimer later worked with Thomas Edison in 1890 at the Edison Electric Light Company as a patent expert and chief draftsman. While at Edison, he wrote the book Incandescent Electric Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System. Latimer’s electrical expertise led him to become one of the company’s charter members. Electricity wasn’t all Latimer was interested in. He also put his mind toward the telephone. While the credit is given to Alexander Graham Bell, it is actually Latimer’s drawings that Bell used to patent the telephone in 1876.

These early businessmen and women have provided the groundwork for future Black businesspeople to follow in their footsteps.

Businesspeople of the Twentieth Century

Lonnie Johnson should be well known to kids who grew up in the ‘90s, since he is the inventor of the Super Soaker, one of the biggest toys of that era. Johnson is the president and founder of Johnson Research and Development Co., Inc., as well as several other companies in science and real estate. As a Tuskegee graduate, he started out his career as a research engineer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory before joining the Air Force and serving as the acting chief of the Air Force Weapons Laboratory’s Space Nuclear Power Safety Section. In 1979, he joined NASA as a Senior Systems Engineer within their Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he was part of the team that worked on the Galileo mission to Jupiter. He returned to the Air Force in 1982 and acted as the Advanced Space Systems Requirements Officer at Strategic Air Command. He also came back to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1987, where he worked on the Mars Observer project and was the fault protection engineer during the beginning stages of NASA’s Cassini project.

After his time in NASA, he created his own engineering firm in 1989 and developed the toy that became every kid’s dream, the Super Soaker. He licensed his invention to the Larami Corporation, and the toy was an instant hit, earning over two hundred million dollars in sales and becoming the number one toy in the nation. The toy became even bigger once Larami was sold to Hasbro, the second largest toy manufacturer in the US. The Super Soaker isn’t Johnson’s only invention; he has over a hundred patents to his name with over twenty more pending, and his products include a new generation of rechargeable battery technology and thermodynamic energy conversion technology.

James Edward Maceo West has helped many in the music business create better sounding art. Born in Virginia in 1931, West currently holds over 250 US and foreign patents for microphone design and production and techniques for creating polymer foil electrets. West received a master’s degree in physics from Temple University in 1957. In 1962, West invented the foil electret microphone while working on instruments for human hearing research. The invention has had immense popularity throughout the industry; about 90 percent of more than two billion microphones are based on this invention. Even more impressive: many of our everyday products, including camcorders, telephones, baby monitors, recording devices and hearing aids are also built with this invention. West continues changing the world with his inventions. His latest one? A device to detect pneumonia in the lungs of infants. And for Black American burgeoning inventors, West provides support with the Corporate Research Fellowship Program for graduate students pursuing terminal degrees in the sciences. Combined with his Summer Research Program, he has given five hundred non-White grad students their chance in the science industry. West also cofounded the Association of Black Laboratory Employees. The group was formed to address the concerns of Black employees within Bell Laboratories.

You know that home security system many parents have? The one that kids have to remember the code for? Guess what? It’s a high-tech version of the original system developed by a Black woman who wanted to feel safer in her neighborhood. Marie Van Brittan Brown is credited with inventing the home security system. Born in 1922 in New York City, Brown, who worked as a nurse by trade, came up with her idea for the closed-circuit television security system in 1966 with her husband Albert Brown when she realized the police in her area were responding too slowly to emergencies on her street. She probably felt like she’d have to rely on herself since the actual police weren’t doing their job. Thus, the home security system was born, so Brown could have peace of mind while staying at home alone.

One could see her invention as an indictment on the local police, since it’s not said whether or not the police were slow to her neighborhood because of racist reasons or because of an actual backlog of crime they were trying to attend to. We can give them the benefit of the doubt and say that maybe the police were understaffed. Regardless, Brown’s invention showed that there was a gap in the city’s protection services for its citizens, and her invention found a needy market that still exists today.

Her system is essentially what all home security systems are based on; even though there have been some twenty-first century updates including smartphone technology, the basic setup for home security rests on Brown’s original idea. Brown was given the Award for the National Scientists Committee for her invention. She died in 1999.

Heart health is what many Americans are concerned with today, and one of the ways Americans find relief is through the installation of a pacemaker, which helps regulate the heart’s beating functions. Many Americans have to give thanks to Otis Boykin who created the pacemaker, which has saved countless lives.

Born in Texas in 1920, Boykin graduated from Fisk College in 1941 and started his career at Magic Radio and TV Corporation and Nilsen Research Laboratories. Boykin invented products on his own while he tried to develop his own company, Boykin-Fruth Incorporated, with twenty-six patents associated with him, including the control unit for the pacemaker as well as the wire precision resistor used in TVs and radios. He also created a device that can withstand extreme temperature changes and pressure. Because it was cheaper and more reliable than others like it already out there, Boykin’s device became highly sought after by IBM for computers and the US military for guided missiles. It’s darkly ironic that he died in 1982 from heart failure of all things. Boykin’s inventions have helped doctors and surgeons give many Americans a new lease on life. So if your parents or grandparents are able to have renewed health because of a pacemaker, pour some out for Boykin, who made it all possible.

Frederick McKinley Jones’s inventions have impacted many areas of American life, from refrigeration to movie theaters. Born in 1893 in Ohio, he served in World War I in France before coming home and starting a job as a garage mechanic. Jones began inventing based on his own self-taught knowledge, with his first invention being a self-starting gasoline motor. As he transitioned from mechanic work toward working at a steamship and a hotel, he did more inventing and design work, including designing and building racecars after moving to Hallock, Minnesota. Incredibly, one of his cars, Number 15, was able to drive faster than an airplane.

Jones’s jack of all trades mentality kept him inventing new products, including adapters for silent movie projectors, allowing movie theaters to play talking films. He also invented a machine for the box office that issued tickets and provided change to customers. For those of you who have grown up in snowy areas, you might be accustomed to seeing a snowmobile or two—Jones invented that too.

The area he has the most patents in, however, is in refrigeration with forty total. One of those inventions includes the first automatic refrigeration system for long-haul trucks and railroad cars, which eliminated food spoilage during shipping and allowed Americans all across the country to eat fresh produce no matter where they lived. His work in refrigeration led him to create the Thermo-King Corporation in 1935, where he continued to change the world of long-distance food shipping. Jones died in 1961.

Atlanta owes a debt of thanks to Herman J. Russell, who started his real estate empire in 1946 by buying a lot where he would build a duplex. This property started Russell’s business of creating business in segregated Atlanta by developing many real estate investments and creating a construction company that would become one of the largest Black-owned companies in the nation and the largest Minority Business Enterprise (MBE) real estate firm in the country.

Russell’s slate of businesses includes H.J. Russell and Company, the umbrella company which housed other companies including H.J. Russell Construction Company, Paradise Management Inc., DDR International, H. J. Russell Plastering Company and Southeast Land Development Company. Russell’s projects turned Atlanta into what it is today, with buildings such as the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, Philips Arena (now known as State Farm Arena), Turner Field and the Georgia Dome—all included in his portfolio. By 1994, H. J. Russel and Company grossed around $150 million with offices throughout the country, including in Miami and New York City.

Russell also used his money to help further Black prosperity by becoming the first Black member and eventually the second Black president of the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce. He contributed to the success of Maynard Jackson’s mayoral election campaign, leading to Jackson becoming Atlanta’s first Black mayor, and he also helped behind the scenes with the civil rights movement with friends like Martin Luther King Jr.

Reginald Lewis is described as the “richest Black man in America,” and was estimated to be worth at least one billion dollars by 1992. Lewis’s status made his business, TLC Beatrice International, the first Black-owned business to gross one billion d0llars in annual sales. Born in 1942 in Baltimore, Lewis attended Harvard Law School as the only person in the history of the school to be admitted before actually applying. In 1970, he and his associates established the first Black-owned law firm in Wall Street and used his legal expertise to develop investments in minority-owned businesses, which led him to become special counsel for big brands such as Equitable Life (now known as AXA) and General Foods. He also worked as counsel for the Commission for Racial Justice and successfully lobbied for North Carolina to pay interest on the bond for the Wilmington Ten, nine men and one woman who were wrongly convicted of arson and conspiracy in 1971 and served almost ten years in jail before an appeal granted them release.

The road to one billion d0llars started with Lewis’s TLC Group, L.P., established in 1983. The first acquisition he made under his new company was the McCall Pattern Company, which he bought for $22.5 million. Under his leadership, McCall’s had two of its most profitable years in its 113-year history, and in 1987, he sold McCalls for $65 million. He was also able to buy Beatrice Foods for $985 million, making his company the only US company to engage in the largest leverage buyout of overseas assets at the time. The newly restructured company, TLC Beatrice International, became the one billion dollar juggernaut that made Lewis a history-making Black businessman. Unfortunately, Lewis died unexpectedly in 1993 at the age of fifty due to a short illness. His legacy has certainly paved the way for others like rapper-turned Tidal mogul Jay-Z, who famously rapped, “I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man.”

Blackness in Business

What can we learn from these men and women? I think the best thing we can take away is how much Black history surrounds us, even when we aren’t thinking about it. When you look at a traffic light or a simple zigzag stitch on a piece of clothing, you’re looking at a Black American invention. When you buy hair products or set your alarm system, you’re looking at the impact of Black Americans on our everyday lives. There is no part of America that Black Americans haven’t impacted, and it shows how we are a much more integral part of society than the history books would lead you to think.