Читать книгу Photographic Guide to the Birds of Malaysia & Singapore - Morten Strange - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

The joy of birdwatching

Birds fascinate us more than any other group of fauna, perhaps because birds are found everywhere. They have colonised all corners of the earth, from the most inhospitable Arctic and Antarctic regions to bone-dry subtropical deserts and remote oceanic islands. Their dazzling power of flight never ceases to amaze us, and, perhaps most important of all, they are relatively easy to observe, since birds are usually active by day and thrive in our near surroundings. Also, their senses are much like our own—they rely mainly on eyesight and hearing—and therefore react much like we do and are easy for us to identify with.

You can watch birds from your window wherever you live. When you walk out into the nearby park or field there will be more birds to see. If you observe closely you will begin to recognise new species; some you see each time you go out, while others are rare and only turn up once in a while or at certain times of the year. Most birdwatchers develop a local patch where they go regularly. When you travel to another habitat, region, country, or even another altitude, you will find different birds to watch. It is this wonderful diversity that makes birdwatching so exciting.

Even though birds have been studied more thoroughly than any other class of animal, new information still surfaces every year. In 1991 a group of young Danish scientists found a new species of pheasant, the Udzungwa Forest-partridge, deep in the forests of Tanzania in Africa. This pheasant turned out to be related to the Arborophila hill-partridges of Southeast Asia, and was placed in its own monotypic genus when described in 1994. For details see del Hoyo et al. Vol 2 (1994). Other new species still turn up once in a while, adding to the 9,704 species already recognised by Collar et al (1994). And since taxonomic studies are on-going (see How to Use This Book) more discoveries and changes can be expected in future years.

The study and interpretation of bird behavior and habits also continues. For a marvellous worldwide collection of new and astonishing information see David Attenborough's television series, The Life of Birds, produced by the BBC and the associated book, Attenborough (1998).

In our region, outstanding research has been conducted by the Asian Hornbill Network based at Mahidol University in Thailand, see Poonswad and Kemp (1993). After intensive initial research in Khao Yai National Park and later in Huai Kha Khaeng National Park in west Thailand, the project expanded into south Thailand, part of the Sunda subregion. During the 1998 breeding season, an astonishing 80 occupied hornbill nests, representing 6 different species, were observed in this area alone—a staggering number considering the huge and remote primary forest terrain that had to be covered. The observations and documentation of this network has completely transformed our insight into one of the most fascinating rainforest bird families of all. The network is currently expanding into other Southeast Asian countries such as Indonesia, Myanmar and Indochina.

Birding techniques

Birdwatching can be enjoyed without much equipment, but a good pair of binoculars definitely helps. The technology is simple. Binoculars are described by two sets of numbers, the first being the magnification, and the second the front lens diameter in millimetres. In other words, looking at a bird through a 10x40 pair of binoculars makes a bird 10 metres away appear as if it were one metre in front of you, and the four-centimetre lenses should give a reasonably bright image. A 7x42 pair will produce a smaller, but significantly brighter, image.

Since binoculars have few mechanical parts; a pair will last you a long time—probably a lifetime, unless you lose them, since the top brands give a 30-year guarantee. Therefore it pays to select the best pair you can possibly afford, so that you won't waste money upgrading later. Selecting the appropriate pair can be difficult, because so many brands and types are available on the market. Consult an experienced birdwatcher or a dealer that you trust. Optical quality varies enormously; good resolution, clarity and colour reproduction is vital. As with most other things you get what you pay for, so pick a pair that is a little more expensive than what you had in mind and you will be happier in the long run.

A telescope, while slower to operate since a tripod is required to keep it steady, has the advantage of interchangeable eyepieces, allowing for different magnifications. Quality telescopes have fixed magnifications in the range of 20-30 times, and some zoom to 60x, but then the image is not as clear. A 'scope' is useful in open country and on remote mudflats, and can help pick out stationary forest birds. It is especially useful in group birdwatching as it allows more people to observe the bird once it is in the frame.

Birdwatching is a social exercise. Go with someone more experienced than yourself in the beginning, join a nature society and attend their outings, in this way you will be introduced to the best locations in your area. It is best to remain quiet and respect those in the group who take this hobby rather seriously. If you do go on your own, take a small note pad and make notes on any bird that you do not recognise. Look for diagnostic features such as bill and tail shape and distinct colour bands on head or wings, and write down details of what you see. You can always consult your field guide later, once the bird has flown off.

As you become more experienced you will find that bird identification is often done quickly, using the so-called 'jizz' of the bird. This slang expression used by birders is derived from 'gis', an achronym for General Impression and Shape, in US Air Force terminology. The jizz of that small garden bird hopping through the bushes lets you know right away that it is a tailorbird of some kind. Then, as you examine it more closely the pale vent and elongated tail tells you that the bird is a male Common Tailorbird in breeding plumage.

You will find that birds are individuals and show some disparities, even within the same species. Some are more tame than others; during moulting the plumage might not be quite the usual colour, while some species include colour morphs—the Oriental Honey-buzzard varies from all-brown to almost snow-white. In fact you can learn to recognise individual birds which regularly visit your garden or balcony.

Some birdwatchers go on to study the subtle differences of subspecies. Others keep databases of all their observations, most importantly a world list of all species seen. Before you know it, adding to this list becomes something of a compulsive urge, and a so-called 'twitcher' is born—a birdwatcher who travels the globe in restless pursuit of new bird species.

Some birdwatchers carry tape recorders and collect bird calls, while others produce photographs and video recordings. Photographing birds is no easy task. Many birdwatchers have found out that twitching for new species or undertaking a serious survey is totally incompatible with the production of quality photographs, which requires that you walk slowly (the heavy equipment alone slows you down) or that you stay absolutely still in one place. At any rate, you seem to get the best results if you stop chasing the birds and let them come to you instead—by staying motionless or hiding by a fruiting or flowering tree, a forest clearing, in a tree canopy, by a pool of water, a nest or some suitable place that will attract one or more birds. You do not see that many different species this way, but you will get to know the ones you do see intimately, and most importantly you may produce rare documentary material that can be shared with others.

But strictly speaking, apart from binoculars, a birdwatcher really only needs one other tool to successfully pursue his hobby: a field guide identifying the birds in his area. This guide should be complete with all species that one could possibly come across illustrated in colour. Luckily, several such guides exist for parts of this region, notably Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Other important books are handbooks which are, in fact, large books with more detailed accounts of the bird habits than identification field guides provide, e.g. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Monographs featuring particular families also give more detailed information on a smaller selection of birds.

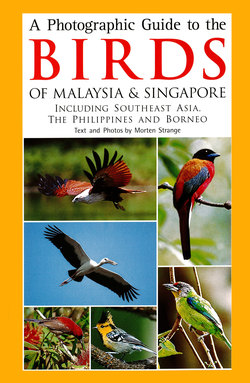

And then there are the photographic guides such as this volume. Complete photographic guides featuring every species are available for areas like Europe and Australia, but one for Southeast Asia, with over 1,400, species would not really be practical and, besides, photographs of all species are simply not available. What a photographic guide can do here is supplement the plates based on drawings in national field guides with photographs from the field. Even the best illustration will contain small discrepancies. Look at the bulbul plates in Birds of Thailand by Lekagul and Round (1991) and compare the Olive-winged Bulbul, Streak-eared Bulbul, Cream-vented Bulbul, Grey-eyed Bulbul and Buff-vented Bulbul there with what the birds really look like in this book and you will see my point. Photographs provide an invaluable source of reference, especially for hard-to-identify groups of bird with many similar species like bulbuls, babblers, warblers and shorebirds. In fact illustrators use (among other things) photographs when they produce field guide plates.

Photographic guides mainly feature those birds most likely to be met in the field—precisely because these are the species that will be available in photographs. The birds in the photos appear exactly as you will encounter them with no artistic adjustments.

Habitats

One of the most fascinating aspects of birdwatching is the study of the way birds depend on their surroundings and the way birdlife changes with conditions. These changes are often gradual and many birds move between habitats—the Scaly-breasted Munia, for instance, can be found both in gardens, open country, wetlands and even beach-side grasses. Furthermore, definition of habitats are not always easy—the many types of lowland forest in this region, for example, makes it unsafe to generalise too categorically.

However, one also encounters many strictly stenotopic birds (birds confined to only one habitat), especially forest birds, mangrove species and birds occurring within narrow altitudinal ranges. Knowing which birds to expect within different habitat types makes the 'work' of identifying the many species much easier. We still find the habitats described in Strange and Jeyarajasingam (1993) the most relevant. There are five main categories.

Gardens and Parks are the most disturbed and artificial of all habitats of course, but they are highly productive, especially if managed sensitively. If you have your own garden, much can be done by planting a selection of fruiting trees to attract pigeons, bulbuls, starlings, the Black-naped Oriole and Coppersmith Barbet, and parrots if forest is nearby. Do not spray against insects if you can avoid it, to allow warblers and flycatchers to settle. Bushes with nectar-rich red flowers will attract sunbirds and if you are lucky a pair of Olive-backed Sunbirds might build their pouch nest in your garden or even in a potted plant on a balcony high above the roar of the traffic as they have been known to do.

Birds in parks and gardens often become used to plenty of human activity and become almost tame. Even shy raptors like the Shikra or the Japanese Sparrowhawk will visit parks, simply because of the abundance of small birds for them to catch. At night listen for the call of the Collared Scops-owl and the Large-tailed Nightjar, and during the winter season keep an eye out for rare visitors from the north, including certain forest birds that might turn up during migration.

Open Country is bee-eater, munia, coucal and shrike territory, although some birds such as the White-throated Kingfisher and others occur in both areas. Swifts and swallows fly overhead. A totally different avifauna inhabits the terrain around wet patches or open fresh water. Many species of heron, rail, duck and snipe are mainly or only found here. No wet field in Southeast Asia is complete without a party of foraging Cattle Egrets. If you are lucky you will locate a weaver colony— the Streaked Weaver prefers the tall grasses and low bushes, the Baya Weaver builds higher in trees and coconut palms, but either species provides captivating, non-stop action with birds calling, displaying, building and flying constantly to and fro.

At the Coast birds abound, especially on sheltered mudflats, and often where a large river joins the sea. Some species also occur around fresh water wetlands but most will be different species. Unless removed by developers, mangrove forests thrive along such sheltered shores and are home to a few specialised birds such as the Mangrove Pitta, Mangrove Blue Flycatcher, Ashy Tailorbird and Copper-throated Sunbird. Other mangrove birds such as the Pied Fantail, Mangrove Whistler, Collared Kingfisher and Laced Woodpecker are less specialised and turn up in nearby woodlands and gardens as well.

Storks are rare in this region, but this is the place to see them. At low tide, storks and many herons and egrets flock to feed on the exposed mudflats in front of the mangroves. Almost all shorebirds (plovers and sandpipers) in this region are migratory. The diversity can be somewhat confusing for the beginner (and for the experienced birder for that matter), especially since it is difficult to get close to shore-birds feeding far out on boggy mudflats. In fact, some birdwatchers get hooked on shorebirds and find the similarities and the differences a challenge. Exposed sandy seashores and rocky coastlines are less productive, but some plovers and sandpipers prefer this habitat, as does the resident Pacific Reef-egret. The Little Heron is likely to turn up wherever there is water.

Tropical Asia has few gulls, but further north in China they become more numerous although no species Stay to breed in this area, except terns, which breed mainly on remote offshore islets. If you have a friend who owns a boat, catch a ride offshore in the South China Sea. Swim to some remote reef during April or May and there you can walk among the breeding sea birds, with terns screaming at you overhead, boobies with their young on the ground, and the majestic White-bellied Sea-eagle soaring in the distance—another of the great birding spectacles this region has to offer. Do not stay long though as the hot sun might damage exposed eggs and young.

Lowland forests are the prime habitat of all Southeast Asia. More birds can be found here than in any other environment and furthermore most are sedentary residents found here all year round, a great number of which are restricted to this region and parts of Indonesia.

Yes, birdwatching in the forest is as tough as it gets. In rainforest, the trees grow to a height of 30 metres or more, and the foliage is massive. Less than two percent of the outside light reaches the forest floor and the humidity stays near 100 percent, even in the afternoon. But then, forest birdwatching is also the most rewarding. You can walk the same forest trail twenty times, week after week, and then the twenty-first time you might see a species you have never seen before in your life, such is the diversity and the scarcity of forest residents.

Conditions are challenging, even in the somewhat lower deciduous forests further north. In addition to the poor viewing conditions the birds are shy and take off at the least disturbance. In general it is better to visit during the dry season, from December to February, and go where the forest is less dense and where many migratory warblers, thrushes and flycatchers augment the resident bird fauna.

Pheasants, hornbills, broadbills, woodpeckers, leafbirds, babblers and flowerpeckers are almost exclusively forest bird families; night-birds, bulbuls, drongos, cuckoo-shrikes and flycatchers are also well represented.

As you proceed higher, the avifauna changes. At 900 metres you enter the montane forest where you will discover a totally different set of birds. This astonishing transformation is once again a highlight of birdwatching in this region. You can drive for a couple of hours from Kuala Lumpur to Fraser's Hill in Malaysia, or from Chiang Mai to Doi Inthanon in Thailand, and so profound is the change that you might well have crossed the ocean to another faunal region. You will then have to begin familiarising yourself with 50 or 60 new species that you simply will never find in the lowlands.

Insect life is abundant at montane elevations and insectivorous bird families such as babblers, warblers and flycatchers are especially well represented, but almost all the other forest bird families such as pigeons, bulbuls, broadbills, cuckoo-shrikes, thrushes, fantails, sunbirds and flowerpeckers have one or a few representatives in the mountains.

The higher reaches of the upper montane habitat, above 2,400 metres, and the alpine habitat near and above the tree limit are not of that much interest in this region, simply because there is little of it. It only exists in the Himalayan foothills of Myanmar and Yunnan (south China), which are not very accessible to tourists, and in Sabah within the Kinabalu National Park. At Kinabalu the subcamp at 3,400 metres is where the alpine habitat starts and this is really as far as birders need to go. Pushing all the way to the summit at 4,101 metres may bring you a nice view and a bout of altitude sickness, but no significant bird sightings apart from the occasional White-bellied Swiftlet, which is better observed at sea level.

The bird year

The region covered by this book is above the Equator and is part of the northern hemisphere. Close to the Equator, from peninsular Thailand and the so-called Tenasserim part of Myanmar and south, tropical conditions prevail, with heavy rainfall all year round, and insignificant changes in the seasons. Even then, the breeding of resident birds is not evenly spread throughout the year. Surveys show that most birds breed at the beginning of the year, from February towards the end of the northeast monsoon season, which dumps more rain than usual over most of the area during the months from November to January. Breeding peaks between April and May, and lasts until June or July, with some birds such as seabirds breeding into August. It is rare to find any nests in the later part of the year.

Actually, it is not easy to find nests in the tropics. Many birds build high in remote forest areas and within dense foliage. But the breeding season is an important time for the birdwatcher, because males tend to mark their territory aggressively, so there are more calls and often the birds are somewhat bolder and easier to observe at this time. Towards the end of the breeding season juveniles appear and add to the activity. Passerines typically feed their young for some time after they fledge, and many breeding records are established by observing the feeding.

Above the 50th parallel, a change to a more seasonal climate occurs. The change is complete above the 20th parallel, where the climate is subtropical with a distinct hot and cold season. Significant local variations prevail, but in general these northern regions experience a cold season with little rainfall lasting from December to February, Over most parts of continental Thailand and Indochina, 80 percent of precipitation falls during the southwest monsoon from May to October, while the cold months are very dry. Breeding in this region is seasonal, with most forest birds breeding in the spring, which is typical for northern hemisphere birds. However, evidence suggests that waterbirds may locally prefer to nest during the end of the wet season, from July into January, but this needs further verification.

Southeast Asia lies towards the end of the East Asia migratory flyway. Migrants from temperate, subarctic and arctic parts of Asia converge on the region during the northern winter. Some pass through during peak migration from September to November and on the return flight from March to April. Many others go no further and make the region their winter quarters.

The actual movement of flying birds is difficult to observe in this region, since most species tend to change location at night, or fly high, out of sight. However, they tend to follow the coastlines, and passage migrants and winter visitors can turn up anywhere depending on habitat requirements. Coastal mudflats (for the water-dependent species) and wooded areas just behind the beach (for arboreal birds) are particularly good places to birdwatch during the winter season.

In conclusion, the beginning of the year is a good time to visit Southeast Asia. At this time the northern subtropical areas experience cool, dry weather and many migrants augment the local avifauna. Towards the end of winter into early spring, the resident birds become more active and conspicuous. In tropical areas, the heavy rainfalls of December subside about this time and the many resident forest birds become more vocal and daring. Alternatively, try to visit from September to November after the subtropical rains, when the northern migrants arrive, but before the tropical monsoons begin. In the subtropics watch for breeding waterbirds.

Places to go

Birds do not recognise political demarcations, so national boundaries are really not very useful when describing the avifauna of a region, however people do, and active birdwatchers keep lists, and tally species they have seen within certain countries. Within the region covered in this volume, some major political entities exist, thus in the following table we list the nations and territories most visited by birdwatchers. Endemics refer to restricted range species found only in that country, except for East Malaysia and Brunei where numbers refer to Borneo endemics.

Just how many birds can one see in total in this region? Obviously many of the species listed under countries will be repeats. For a measurement of the total diversity Robson (2000) lists 1,251 species, King et al (1975) list 62 additional ones for Taiwan, Hainan. MacKinnon & Phillipps list 37 species endemic to Borneo, and Dickinson et al. (1991) has 169 endemics for the Philippines. Calculated this way about 1,519 different birds are found in Southeast Asia. But if you see the 668 covered in this volume, you will have done well.

Conservation

Many of the birds in this book are adaptable and prolific. The Yellow-bellied Prinia readily invades forest areas cleared for development; and the Common Myna visits gardens and even invades people's homes to grab food. These birds have no problem surviving, but others adapt poorly to changes in their environment, so if their forest is removed or their island built over, they have no place to go. They need our help if they are to survive.

'Conservation begins with enjoyment' says the English comedian and professional birdwatcher Bill Oddie. In the 1994 BirdLife International study, published in Collar et al. (1994), it was documented that no less than 1,111 bird species comprising 11 percent of the world's avifauna could be regarded as globally threatened with extinction. A further 875 (or nine percent) was near-threatened. In other words, one out of five of all birds in the world is doing poorly or about to disappear.

Even in this book, which mainly features the easy-to-see species, 29 birds are globally threatened, a further 31 birds fall into the near-threatened category, which totals nine percent of the species covered.

The BirdLife study also revealed that most of the threatened birds live in the tropics, in countries with relatively low national incomes. They are forest birds (65 percent) and the main causes for their decline are habitat loss, a small range or population, and hunting and trapping. Unfortunately, most birds are unable to defend themselves. This is where Bill Oddie's enjoyment factor comes in. Birdwatching is fun, exciting, intellectually stimulating and as more people take up the interest they wilt tend to appreciate the natural world more. This has happened in the West and is now happening in the East.

But first of all, reliable data is necessary before action can be taken. Together with BirdLife International, local nature societies and birdwatching clubs continuously document the status of selected species and sites as part of the Asian Red Data book project and surveys for Important Bird Area inventories.

In this era of globalisation, national efforts are not enough. The rich biodiversity is available for everybody to enjoy and likewise we all have a responsibility to monitor and protect it. Birdwatchers from elsewhere can visit Southeast Asia to enjoy what the region has to offer, and they should, in turn, make their expertise and observations available to national agencies. Once we know where to direct our priorities, we can initiate programs to reverse the decline of so many beautiful birds.

We must stop the indiscriminate developing of natural bird habitats, cease polluting the environment and start rebuilding what has already been damaged. We must heed the advice of those who have studied biodiversity and take into consideration the environmental effects of development just as seriously as we take the advice of economists and technicians before making decisions on how to progress.

In 1997, the Southeast Asian region experienced an economic setback partly due to an unbalanced and consumer-focused type of development. One hopes that the next bout of economic growth will be more sensitive to a total quality of life, including an appreciation for our natural heritage, the diversity of life, the health of the environment and the well-being of the other lifeforms around us—including the birds.

Baya Weaver at nest entrance.