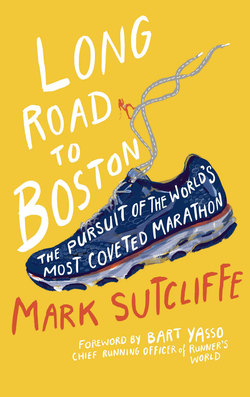

Читать книгу Long Road to Boston - Mr Mark Sutcliffe - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PROLOGUE

ОглавлениеMay 18, 2014

It’s the final mile of the Poconos Run for the Red Marathon in Stroudsberg, Pennsylvania, and I am still on pace to achieve the goal I’ve been working toward for years: to run the fastest marathon of my life and qualify for the world’s most coveted race, the Boston Marathon.

But there’s a problem, sneaking up on me like footsteps from behind: my calf muscles are gradually starting to seize up. It is, lamentably, a familiar development: this has happened to me in at least five other marathons and it rarely ends well. It starts with an occasional twinge every few minutes, harmless but ominous. Once in a while, if I’m lucky, it doesn’t escalate from there. More often, though, it steadily intensifies until there is a painful, debilitating and soul-crushing spasm every time my foot strikes the pavement. In one race, even after I stopped running and started walking, the contractions were so intense and incapacitating that I almost fell over.

I dread this possibility in every marathon. No matter how smoothly the race is being run, the backs of my legs are always in the back of my mind. Will it happen? How soon? And how bad will it get?

Here in Pennsylvania, it’s still manageable, but my stride is changing from a solid, controlled pace to a quick, desperate shuffle. I feel like Lightning McQueen in the opening scene of my son’s favorite movie, Cars, hopping frantically toward the checkered flag with two flat tires and a pair of challengers bearing down on him. How long will it be before I am walking or stumbling, watching the minutes pass me by like faster runners, until my goal is lost one more time?

As I’ve learned from experience, no matter how well you are doing halfway or even farther into a marathon, you can never be optimistic until you see the finish line. You can run a great race for 20 miles, then blow it all if your legs or your energy give out. It’s like mounting an incredible comeback in a championship basketball game, standing at the free-throw line with a chance to sink the go-ahead points, and watching your shots clunk off the rim like bricks. A marathon can create such fulfilment and validation, but when it falls apart, it can shatter the spirit. You slow down or stop while the rest of the field slips past you, vanishing into the distance along with your dreams.

I haven’t completely given up hope. But then I’m struck by what seems to be the decisive blow. The pace bunny for my Boston- qualifying time of three hours and twenty-five minutes zooms past me on my right. Traveling at a prescribed pace, he is the personification of my target; success or failure comes down to whether I finish ahead of or behind him. For twenty-five miles I have stayed a safe distance in front of him, but now he is disappearing down the road ahead. Like time, the pace bunny waits for no one. He has chased me down and left me in his wake.

It’s over, I think to myself. Yet another failed attempt. Once again I’ve trained for months, running six times a week, doing speed work and long runs, eating (mostly) the right foods and managing my weight. Once again I’ve left my family behind to travel to a race that is supposed to have favorable conditions for a fast result. Once again I will return empty-handed. I feel like Homer Simpson thinking he will cross Springfield Gorge on a skateboard – I’m going to make it! – only to fall suddenly short of the target and tumble perilously down the cliff.

It has been a long journey – and I’m not referring to the last twenty-five miles. For as long as I can remember, even before I started running, I’ve wanted to do the Boston Marathon. For six years, it’s been a stated objective. And for the past four marathons, my only focus has been to finish in a time fast enough to qualify for the oldest and most cherished marathon on the planet. For more than two years I’ve trained exclusively for one reason, some five or six hundred runs covering four thousand miles, with only one thing on my mind.

And I’ve come agonizingly close. In my last race, I was twenty- two seconds from the goal, less than one second per mile. My results in training have told me that a Boston-qualifying time is within my grasp. And yet I can’t seem to pull everything together when it counts. Something always goes wrong and I miss the target. The pattern seems to be repeating itself in this, my twentieth marathon.

I’m not sure how much more of this I can take. I stop running and start walking. And I begin to think about what I will tell my wife and all those who believed in me, who told me I could do it: Nope. I came up short again.