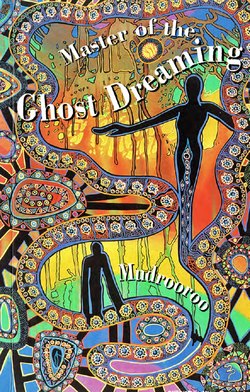

Читать книгу Master of the Ghost Dreaming - Mudrooroo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I

ОглавлениеOnce, Morning Star had shifted from its course and had drifted far from the dawn. It continued to shine, continued to be a beacon, but became not the harbinger of the morning, of the light, but a marker of the density of the night which has overtaken us. It illuminates our misery and tugs our souls far from day. Our spirits roam the realm of the ghosts – an unfriendly land where trees and plants, insects and serpents, animals and humans wither and suffer.

Now, we, the pitiful fragments of once strong families suffer on in exile. Pulled by Evening Star into the realm of ghosts, only some of us live on, kept alive by our hope that we shall escape this plane of fear and pain. All around us is the darkness of the night; all around us is an underlying silence of a land of death. Where are the crescendos of Cicada; the watching eyes of Kangaroo; the scuffling of Bandicoot? They have been swept from this land. All are gone. Only Crow, he the one close to death and corpses, remains to gloat over us – we, the ones surrounded by death. Surrounded by ghosts, worse, in the arms of ghosts we die to ourselves. And even in that death, there is no surcease. Lost is the way to the skyland. Our souls wander forlornly in the land of ghosts. Our spirits become their play things; our bodies their food, to be ripped apart, and our gnawed bones are scattered. We are in despair; we are sickening unto death; we call to be healed. Anxiously we wait for the ceremony to begin. We wait for our mapan, the Master of the Ghost Dreaming to deliver us. From him we demand release from the land of ghosts. We demand healing from our shaman, Jangamuttuk: he who is the custodian of the Ghost Dreaming; he who can sing the way of release through song ...

Thus Jangamuttuk interpreted the collective feelings of his people, as he waited for the correct moment to begin the ceremony. The feeling needed to rise just as the Hunter had to move the line of his spear towards Wombat. Now ...

The rap-rap, rap-rap of his clapsticks shattered the silence of the darkness. The sharp raps disappeared out and out, hit some obstruction and circled returning. Raprap, rap-rap. Instantly fires were kindled. Little flames flickered, grew stronger with the chant completing the square. ‘Fire, flickering, flame grows, flame grows.’ Now the square clearing was outlined by the fires. Jangamuttuk’s tribespeople stood in a solemn row.

Male and female moved next to each other. The males were naked except for the initiated men who proudly wore the incised pubic shell of their clans; the women subjected to the new Christian faith wore a long skirt, but above their waist to perfect the ceremony, they had painted in a lattice work of white lines that which signified a bodice lowcut as in formal European wear. There was even the appearance of a necklace dangling above the cleavage of the breasts. Three: white rows of dots flowed dripping down to just above the three cicatrices of womanhood, passing across the cleavage. In the dip, outlined in red ochre, but appearing dark to invisible in the light of the flames was an eye-shape. To complete their costume, they wore flowers and leafy twigs plaited into their hair and shaped like European women’s hats.

The men’s head ornamentation also signified the European. Civilisation had shorn many. Gone were the elaborate and proud hairstyles of the initiated men. Now they covered up their naked shame under woollen caps; thus replacing the reality for the symbolic. Those few newcomers who had been spared the clip-clipping of Fada’s scissors, arranged their locks into the shape of flat European hats, or piled their hair up around a piece of wood or rolled up cloth so that it might appear in the fire light to be the high helmet of a European soldier. Their body painting had been designed to signify European fashion, both civilian and military. The stripes of military jackets were painted across chests; lapels and buttons, even pockets had been painted with an attention to detail that was quite startling – that is if there were European eyes present to be startled; but for the moment there were none, and even if there had been, it was highly doubtful that the signifiers could have been read. What was the ultimate in a sign system, might still be read as primitive.

Jangamuttuk, dreamer of the ceremony, was painted in like fashion. His work was more elaborate and detailed. A hatch design of red and white encircled his neck in a symbolic collar. Below this were painted the broad lapels of a frockcoat. Four buttons of a spiral design kept the coat closed, and in the vee, the top of a waistcoat peeped out. His legs, and the legs of the male dancers, were painted white with a circular design at the knee.

Now Jangamuttuk, creator and choreographer, checked the company for flaws before the body of the ceremony began. He was not after a realist copy, after all he had no intention of aping the European, but sought for an adaptation of these alien cultural forms appropriate to his own cultural matrix. It was an exciting concept; but it was more than this. There was a ritual need for it to be done. The need for the inclusion of these elements into a ceremony with a far different purpose than mere art. He, the shaman, and purported Master of the Ghost Dreaming, was about to undertake entry into the realm of the ghosts. Not only was he to attempt the act of possession, but he hoped to bring all of his people into contact with the ghost realm so that they could capture the essence of health and well-being, and then break back safely into their own culture and society. This was the purpose of the ceremony. A ceremony which had been dreamt in response to the pleas of his people. He would establish contact. He would enable them to evade the demons of sickness which were weakening and destroying them, and then when they were strong ... but first the ceremony, but first the ceremony.

The master sang to his clapsticks, asking them to allow him entry into their spirit, begging them to sound the necessary rhythms which were important to his craft. They acknowledged him in the rap-rap, rap-rap of a traditional rhythm. The didgeridoo players followed the sharpness of the rhythm, swooping down on it and rising above, or below as their instruments desired. Each didgeridoo player, Jangamuttuk knew, was letting his instrument speak. Now his clapsticks, anxious for direction stopped; the didgeridoos groaned low and hesitated: this was ceremony, serious business. Jangamuttuk took control of his clapsticks. He entered into a rhythm which switched the playing back onto the individual skills of the musicians. They edged into the time, feeling out the possibilities of the play as the rhythm bounced the shaman towards possession and his people into a new kind of dance.

The dancers clasped each other and began a European reel. They kept to the repetitive steps and let the strange rhythm move their feet. It became their master. Each generation including the tragically few children jigged as Jangamuttuk began to sing in perfect ghost accents:

‘They made of me

A ghost down under,

Made for me

A place to plunder,

A place to plunder,

Way down under.’

He finished the verse and began again, picking out individual words in the traditional style. This was far from a euphonious rendering, but it was difficult to range vowels and consonants into an harmonious whole in the ghost language he was using. He finished on the words:

‘Made me made me mad

Ghost place ghost face

Ghost ghost ghost ghost.’

Feeling his consciousness beginning to slip, feeling the night and the dancers begin to ... He began the second stanza:

‘They made of me

A ghost down under,

Gave me a dram,

It tasted like cram;

Real as my dream,

Way, way under.

Under, plunder, thunder,

Way, may, nay, stay

Down, town, down,

Ghost ghost under,

Slam clam ram mam ...’

Mada writhed uneasily, then jerked awake as the burning pain hit her. It began way down in her abdomen and twisted along her spasming bowels. She lay there, desperately trying to come to grips with yet another manifestation of what she had come to accept as her pain, her anguish, her hatred and loathing at being forced to continue living on in this awful colony, isolated far from the nearest decent-sized town on a dreary island, where the weather lurched from violent extreme to violent extreme. No wonder her health suffered, no wonder – and that great clod of her husband didn’t care one iota, nor did her oaf of a son. He never thought of the sacrifices she had made just in bringing him into the world, and both father and son certainly never considered how isolated she felt in this savage land. But she couldn’t blame her son, as that lump beside her was the cause of all their, of all her problems, of her constant state of ill-health. He didn’t care for her at all. It was his meddling in things beyond him that had caused her pain.

The constant burning pulsing of her bowels didn’t allow her the luxury of contemplating her plight in an uncaring land covered with the secretness of the night. Beyond the drawn, thick curtains the alien stars shone and the pain-laden wind rustled the foreboding trees in the threatening forest. The trees pressed in on the civilised square in which lay the mission house, the chapel, the storerooms and the compound for Christianising the natives, before their corpses went to add to the ever increasing number of graves in the cemetery. Too often all this tugged her into depression, but at the moment none of it bothered her. She was safely hidden away behind thick curtains in a refuge which, as much as possible, resembled the imagined sweetness of her sweet home, with its heavy imported furniture and knickknacks, far across the ocean. She sighed alone in exile and with the pain eating away at her. She needed her medicine. Over the years her memories of London had dimmed. Now it was a fairyland free from suffering. How she hated that pig of a husband snorting beside her. Him and his career and his excuse of waiting time out only for the pittance of a pension which would be her deliverance. Him and his altruism. His stupid ideas about serving humanity and taking the message of Christian caring and goodwill to benighted savages like the ones dying all around her. Why, he loved those sable friends of his more than he loved his own wife. He didn’t care one penny for her and how she suffered. She needed the care of expert doctors that could only be found at home, London! There, she had been in the full bloom of health. Illness had begun when she allowed herself to be taken to this colony – to be lodged in a rough establishment and forced there to raise a son, while the father evaded his responsibilities and roamed across the wilderness on what he called his mission of conciliation.

She had had to be the man to her child while he was off in the wilderness up to God alone knows. Now, after all that time of strength, her body had broken down. It was constantly racked by pain. In fact it felt as though it was the battlefield between constantly warring groups of organs. Her pains were the result of the wounds and setbacks of all she had endured in the ever recurring campaigns. Which side would win, or what the result of winning would have on her, and the consciousness of her body, she had no idea; except that it would add further torment. What could she do, but seek to bring a truce in the warfare, and to pacify all the combatants by using the haphazard supply of medicines which arrived on the supply vessel? One medicine above all she valued as a pacifier, laudanum. But her husband, who had the audacity to believe that he knew what was best for her, only allowed three pint bottles per supply ship. These never lasted, never ever lasted. She was so often racked by pain and a little sip morning, noon and night worked wonders for her. It was her special medicine, but that great oaf of a husband refused her a constant supply, just as he refused her every blessed thing else.

He had never loved her. Had only loved himself and that love affair had grown over the years until there was only him and his needs and wants. It – now she realized – had always been like that. The only reason he had married her was that she was above him, and so he had thought that by marrying her he would automatically rise to her level. That would never be and he would remain a member of the lower orders until the day he added his own grave to the others he prayed over. Why, he was little better than the poor convicts they insisted on sending out to rot in the colony. Poor things. She pitied them, but they were all rogues, male or female, and she was better off without having them around. Servants indeed. A lot of thieving rascals. Why, you had to keep an eye on them, morning, noon and night. Now she had those so-called civilised natives for servants, that Ludjee, who had been around her husband for God knows how many years until she had become civilised in conceit. At least, she did her work better than that convict lass she had had: the one who had become mysteriously pregnant and had had to be sent back to the female factory. Hussies the lot of them. Trash, just like that husband of hers with his aspirations to become a gentleman.

Become a gentleman indeed. How she used to laugh, behind his back for sure, but still laugh for all that. Him and his practising hour after hour in front of the mirror to find and keep his aitches. After years of effort, he had succeeded enough to hoodwink those in authority, but for all that, he had only managed to obtain a post on this miserable island where she languished along with him. Superintendent of the Government Mission For Aborigines, indeed! A grand sounding title for a poorly paid job, but then he wasn’t up to anything else. He was so inept at numbers that she had to keep his books for him. Thank God, her daddy had been a shopkeeper and had made sure that everyone in the family could figure. If it wasn’t for her father, God rest his soul, and herself, that worthless man would have stayed the bricklayer he was meant to be. Sweet Jesus, she had been such an innocent ninny to allow herself to be taken in by his sweet words. That’s all he was: words. And that’s all he had, never anything else, and she had allowed him to persuade her to follow him here and to live among an almost extinct tribe of savages.

And here they were, right on schedule, beginning their unearthly din in the middle of the night while she lay in constant suffering, while that great lump of a husband snored on beside her. God, those savages were melodious compared to his bestial snorting. And how healthy they were. Not a sickness among them. No, that wasn’t right. The poor bastards were as badly off as she was. Dying off under the ministering hands of her inept husband. He would be the death of all of them, just as he would be the death of her. Why, when she was well enough to get around, how it hurt to see the little ones lying there so sickly. It made the heart so heavy, but perhaps they were better off away from it all. Sometimes, she thought like that. You know, getting it over once and for all. It would be better off all around. What good was medicine when that unfeeling brute of a husband rationed it out? No good at all. What he should do was give them as much laudanum as they needed. Give us as much laudanum as we need and save us good and proper. No more any of us suffering and calling and singing out our woe, our pain, our ill-health, our need to enter into a realm of health. No more of that – but a constant supply of laudanum would never be, not while that good Christian, the Bringer of Salvation was in charge. Christ, how he snored. Well, he wouldn’t for long.

Savagely, the woman dug her husband in the ribs. He gave an extra loud snort and turned on his side. The cacophony of his snores resumed. Out of tune with the natives singing outside, they angered her so much that her pain disappeared. She hit him savagely across the nose. Startled, he sat up wildly. Aghast at her action, she sought a victim and settled on the convenient victims caterwauling the night away with their pagan cries.

Both now awake, they listened as on the wind came the voice of Jangamuttuk miming out perfectly words in the very voice of her husband. She couldn’t help grinning at him in the darkness.

‘They made of me,

A ghost down under,

Gave me a dram,

It tasted like cram,

Real as my dream

Way, way under.’

The intent of the words rankled her and the grin turned savage. This brute, this brute beside her had lured her out from London in that smug voice. Him and his promises. ‘Stop them, stop them!’ she demanded of her husband.

Fada had rather enjoyed the mimicry. He took great pleasure in the natives and their simple, but effective ways. In fact, so much were they in his regard, that he was in the midst of writing the definitive text about them. Nothing would have suited him better now than to pick up his pen and jot down the rude but simple rune. It was with such amusing anecdotes that he wished to lighten the heavy brief of his volume: the taking of the message of goodwill to the poor natives of the Empire. He sighed at the greatness of his mission.

‘Will you make them stop! I can’t stand it. I’m not asking much of you. I have never asked much of you. Please God, just make them stop. I’ve had enough for one night.’

Fada sighed in annoyance. How could he have dragged this woman all the way across the ocean? How could he, when she so obviously was not a help to him in his mission, more a hindrance? ‘So help me, God,’ but it was so, and he sighed again.

‘Well,’ the demand fell between his bed and his journal.

There would be no rest this night, unless he went to quieten his charges. In many ways this could be made to work for his benefit. Why, it might prove to be the basis of an entire chapter of his volume. The thought pulled him out of bed. His wife groaned at his portly unromantic figure clad in a long nightshirt and with a nightcap pulled low over his balding head. With a deep sigh, she turned and faced the wall, waiting for him to be gone so that she could have a dose of her favourite medicine and achieve blessed sleep.

It was not in the nature of Fada to play the sneak. Thus he strode away from the mission compound and along a track (a visible fruit of his labours), in the direction from which the sound of clapsticks and digeridoos came. With a smile, he waited for the mimicking voice to begin again, but it did not. His eyes adjusted to the starlight and he walked briskly along, sensing that the music did not come from the cemetery at the end of it. A cemetery too quickly populated, he thought. The rhythm came from somewhere to the right and from the forest. Knowing that there were no dangers to be feared from savage or tame animals on the island, he confidently left the track and groped his way through the dark bush. The starlight made the scene tremble and become a romantic wilderness. Trees assumed fantastic shapes. A storm had lately come crashing through the forest. It created havoc among the giant trees. Huge boughs were ripped from the mother trunks and tossed yards away, or had just been pushed down to crack and lean half-detached. It was as if a giant had charged through the bush without heeding the consequences. Fada breathed a prayer of thanks. His flock had been spared from this natural calamity.

The fallen boughs made for rough going. Fada for an instant forgot his good nature, and cursed the tricky devils who sought to hide their shenanigans deep in the forest, but his good humour at once returned. He smiled at the childlike simplicity of his charges who had so skilfully evaded his sight, but who were so unaware that the sounds of their revelry would travel to his ears. Then, through the giant boles of the forest, he saw the flickering of fires. He went forward softly and crept to the edge of a sylvan glade. There in a forest fastness, his charges, supposedly safe from his all-seeing eye, were indulging themselves in a ceremony which reminded him of the mass of the Popish Church of Rome. Fascinated, he stayed hidden in the darkness behind the illumination of the fires. His romantic nature came to the fore. He felt like some elf in spirit watching the mysterious ways of the humans.

Jangamuttuk was afraid in the realm of the ghosts. Soaked through, he huddled sodden as the ground beneath and the air around him. After, or before, now, he reached out for his mapan power living in the pit of his stomach. Standing, he took a long look about him. Mist and the smell of decay. In the distance, but what was distance, close, rose a hill fantastically shaped by the weather of this forbidding country. Such was his human reasoning, but then his special ghost knowledge entered his mind. It was a castle, a dwelling of the higher ghosts who would hold the medicine that would bring health to his people. He had to get inside, but as he looked, it receded from his vision. The tall foreboding walls were unbroken and mocked his fragile humanity. He needed his Dreaming companion. With longing, he sang for him. Sang a song that came from his secret initiation. His clapsticks tapped out the strong rhythm. From his external initiation, the didgeridoos took up the rhythm. He let the sound lift him towards the castle walls. He sang his song again, calling, calling. He fell to earth beside the white walls hazy in the swirling mist. Rain began pelting his naked body, washing away the immunity of the painted symbols. His power began ebbing. Desperately, he clapped his sticks together. The didgeridoos roared out his urgency. Now, a familiar warm wetness passed over his head, and his clapsticks changed to a rhythm of welcome. His power flowed as he looked up at the stone axe-head of Goanna bending to accept him. Now with his special Dreaming companion, Jangamuttuk the shaman laughed as he scrambled up on its head. Now the walls were thin as paperbark to him.

The back of Goanna was ancient and even his sacred skin patterns were faded. Jangamuttuk could remember his first journey with him, then the patterns were clear and well marked. They had gone to form his most sacred body paintings, and in the old days, when culture was strong, the sight of them would have inspired fear in women and children. Now they might be identified, if at all, only as the mark of the Goanna Dreaming. Jangamuttuk lovingly traced some of the patterns. Perhaps next time he would bring along some paints and touch up the designs, though it would be difficult, for the loose skin was pitted and scarred and hung in folds. These afforded him both hand and toe holds, and he had often thought that Goanna made them for the comfort of his rider.

Now, he watched Goanna sum up the scene in two jerky head motions. He lumbered forward a few clumsy steps, gathered himself and raced up the wall. It always amazed Jangamuttuk how swift and agile his Dreaming companion was – and how sure in his knowledge. For as swiftly as he had begun, he stopped beside a narrow opening invisible from below. Pushing his clapsticks through his hair belt, Jangamuttuk squeezed through into a passageway similar to the one leading to the sacred cave where in the not so long ago, when they were in possession of their own land, the tribal bones rested. But now here was there the familiar feel of hard rock, or ancestral power. All along and underfoot were soft skins with the fur turned inwards. The smooth surfaces were covered in designs and figures of such mystical intent, that he wished that he had the time to draw some, but he had to hurry onwards. Testing that the power was still with him, he pulled out his clapsticks and tapped out a jaunty rhythm, a play rhythm that he had often played to the children of his community. A feeling of sadness overtook him, for gone were the times when children could dance carefree to this rhythm. The didgeridoos replied to his sadness and urged him along.

He knew that his time was limited. The atmosphere pressed on him with a sense of disease that threatened him with sickness. But his need and the need of his people cancelled out the sense of foreboding. He wanted health. They wanted health. All were far too depressed to endure the island prison much longer. They were becoming tired of life. Then his need for health met an answering need. Strange scenes threatened to take over his brain. They were of such ghostly intensity that only the strong magic of his shaman nature kept him from going insane with a longing for something that was beyond all his understanding. Unsure of his power, he took on the shape of a spider and darted along a safe strand towards his goal. A slab of wood attempted to bar his way, but he passed through and found himself caught fascinated by the bloated horror that hung in the centre of the web. It had not been his web, but her web. She reeled him in. The slavering jaws fascinated. He was paralysed, unable to escape ... Then the urgency of the didgeridoos danced him free. He changed from a spider back to the shaman, then into his Goanna familiar, then back again as he found himself out of danger.

A ghost female lay on a platform covered with the softest of skins. She was fair to behold. Stark white and luminescent was her skin beneath which, pulsing blue with health, Jangamuttuk could see the richness of her blood. Her lips were of the reddest ochre and her cheeks were rosy and glowing with good health. Her firm breasts rose and fell. She slept the sleep of a being seemingly content in body and spirit, but Jangamuttuk with his insight knew that this was an illusion. A wave of illfeeling from her nightmare shivered her form and before his eyes the fair illusion of her face twisted with a hunger which might never be satisfied. Her longing extruded from her to fix his attention on a small table within reach of her groping hand. On it stood a golden flask. The source of her good health. Before the hand could clasp it, Jangamuttuk snatched it up.

The eyes of the ghost female sprang open. Blue and utterly cold, they held him. Wrenched from a dream in which she was on the verge of finally and utterly achieving complete satisfaction, her hunger erupted in a scream of rage at the human. The female sprang at him. Before the claws could fasten on his throat, he regained his power and sprang aside. Thwarted, she glared at him, readying her body for another attack. This gave him the edge he desperately needed. Thrusting the neck of the flask through his hair belt, he lifted his clapsticks and began a pacifying rhythm. She hung, her body quivering in the urge to spring upon him. Softly, he began to chant:

‘Now the darkness holds my soul ,

His voice keeps me from the source,

Thunder, thunder, lightning strikes

Holds me still in my wretched plight.

And I groan, moan, no pain can quell,

Or hope can quench, the sorrow of my hell,

Down under, living hell down under.’

The truth of the spell safely held her. The didgeridoos swept into a petrifying rhythm while he searched for an escape.

A perfect cube held both of them prisoner. But he was threatened by more than imprisonment. The angry female struggled to free herself from the bonds of rhythm. Jangamuttuk pressed at a slap of wood marking one of the vertical sides. His ghost knowledge failed him. It was only design without function. A small square in the opposite side. Suddenly, he knew that it was the way to escape. He rushed to it. The female glared and lunged at him. The rhythm held her. He thanked his master for the gift of the chant, as he poked his head through the opening and saw, alongside, his Dreaming companion. He grabbed two handfuls of rough skin and swung himself across the broad leathery back. With a rush, he was away with the medicine safely tucked in his belt. From behind came a loud shout of rage, followed by a scream of despair ...

Fada watched entranced as the natives acted out their travesty of the central ritual of a Popish mass. Each couple approached that rascal of a Jangamuttuk and received from what he could have sworn was one of his wife’s old medicine bottles, a drop or two of seemingly precious fluid. This, indeed, would make for another amusing anecdote; but Fada was more than startled when the villain mimicked an awful travesty of his better half’s voice. This was too much of an imposition, especially if she was still awake and listening. Visions of the endless barrage of words he would have to put up with for the rest of the night forced him to act. Stepping into the light of the clearing, he commanded: ‘Stop!’

Petrified by the apparition in the long white garment and nightcap, they instantly obeyed him. It was indeed a ghost summoned hither by the ceremony of their shaman; but he, they knew, had the power to send the apparition back whence it had come.

Jangamuttuk, feeling himself coming out of his trance, hastily said farewell to his Dreaming companion. Satisfied that he had fulfilled his task, he looked up and into the angry eyes of a ghost. He tensed, then relaxed. It was Fada, his tame spirit.

‘Jangamuttuk, you old villain, you will put an end to this immediately.’

‘About to boss,’ Jangamuttuk smiled, humouring him.

‘And did I see you with a bottle of my wife’s medicine?’

Fada, without waiting for an answer, came towards the shaman. Jangamuttuk hastily stood up in case the ghost turned violent. He knew that sometimes Fada took exception to nakedness, and here he was naked except for his shell pubic ornament and his hair belt in which he had thrust his clapsticks. ‘No, boss,’ he replied as he hurriedly made off and out of the clearing.

The rest of the people followed him and Fada, feeling somewhat foolish, was left alone. With a mental note to himself to fix the rascal in the morning, he poked around the spot where Jangamuttuk had been, looking for evidence with which to confront the old man with thievery. Not a thing. Strange, he could have sworn ... and not a stitch on the beggar. With a shrug he dismissed the whole incident and let his good humour return. He stared around the deserted clearing and found himself alone, romantically alone in the wilderness. How he wished for a charcoal stick and a sheet of paper. ‘Deserted ceremonial ground’, would make a fitting title for the sketch. Perhaps (at least he fervently wished) his wife had lapsed into a sleep, leaving him the rest of the night free to make notes on the fascinating ceremony he had witnessed. The body paintings were of such a degree of intricacy that he might not be able to reproduce them in their entirety, but then over the years he had seen enough of native ceremony and body painting to improvise on the design. But these ceremonies, they must stop, and it was his Christian duty to end them. He sighed. The missionary and the anthropologist uneasily shared his soul. The stern Christian knew that these pagan ceremonies had to go, whilst the anthropologist (and the romantic) found a natural joy in them. Was there a middle way which accepted both Christian duty and scientific enquiry? He sighed again, as he left the clearing with a last sad look.

On the way back to his house, his mood lightened as he began to plan out an interesting paper for the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Society. His last effort had elicited a number of most favourable comments from the learned gentlemen of the Society. Now he was sure that with his next publication, he would be well on the way to achieving his ambition to become a member of that august body. He smiled with satisfaction and quickened his pace ... and to think that he had started life off as a bricklayer.