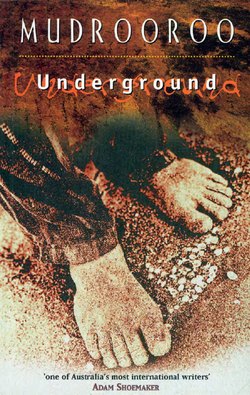

Читать книгу Underground - Mudrooroo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеThe winds had been favourable when we left our island, blowing constantly from the east. They endured for a number of days, then fell away, replaced by spates of southerly squalls which drove us to the land. After some days when these had blown themselves out, we put to sea on an easterly. Our schooner was in good spirits and we raced to the west until the fickle wind reversed itself to force her back on her wake. Worse, this signalled the change of the season and the westerly came down on us laden with a bitter cold, draping our vessel’s rigging in hoar frost. We fashioned cloaks from our blankets, covering them with the skins of kangaroos and wallabies which Wadawaka had collected when we had had to shelter on the mainland. Before, an adventure had erupted about us, we had filled our time with hunting and this now served us well. Our skin-coated blankets kept us somewhat warm, but as the adverse wind continued and the cold endured, most ·of our mob took refuge below decks, where they huddled miserably in the tiny space and complained bitterly.

There was little that we could do. The wind rose into a gale which blasted us back on our course. Wadawaka let the vessel run before it. She didn’t like it that much and slumped along with her head bent low. Every now and again, the knitting needles she had thrust through her hair bobbed and weaved and we might have ended back where we had begun if the gale had not fallen away to a steady wind. She stopped her pitching and yawing, and the deck stayed horizontal. It was some time after this that a man poked his hairy head out of a hatchway, waited for a while as if he did not believe that the world had indeed settled down, then finding that it had, he pulled his weighty body through and onto the deck. He stood there slightly swaying, staring at the white-capped sea with a scowl of dislike.

Although Wadawaka was a big man, this blackfellow towered over him. It was Hercules, who looked like some bulky bear in his hairy cloak. I was standing beside Wadawaka and watched as the giant bear bent down and pulled out his huge waddy, his constant companion. His beard and hair were unkempt and streamed in the wind as he stood before us, muttering fiercely before bellowing: ‘We have had enough of this pitching and rolling. We need the firm earth beneath our feet and the warmth of a campfire to unfreeze our bones.’

Wadawaka stared into his glowering features, then replied with a shrug. ‘What could I do, when the wind howled in her icy rigging and she turned and scurried east. Well, since the tempest has lessened his fury, we’ll run close to the shore in the hopes of finding sheltered anchorage in the lee of an island, then we’ll go ashore.’

Hercules hefted his club and grimaced at the waves as if he would batter them down. The challenge was accepted and a huge wave rose to curve over our stern. As it did so, the giant jumped through the hatchway and dragged the cover across. The wave crashed down and we were tumbled about and along the deck. Luckily, we fell into the bow of the schooner and so escaped being washed overboard. When we had scrambled to our feet, we saw that the sea had spent its fury and now rippled gently beneath our hull.

Wadawaka took the helm from me and corrected our course so that the wind came from the starboard. Our single sail shivered and swung to take it up. The sea was still the gentle ripple; but the waves came from the sides and strangely were translated into a harsh rocking of our hull. From below came groans as a new misery was added to their suffering.

‘Well, if they want to land, they have to endure it,’ Wadawaka said with a puzzled look on his face, for how could such a calm sea set us to such a rocking? He turned the wheel a fraction and the vessel pitched and shuddered so that even he had difficulty keeping his feet. ‘Must be some sort of current,’ he said as he struggled with the wheel. From below came the sound of retching and my stomach turned over in sympathy. Wadawaka the Seaborn showed no sign of being unduly upset at the motion, though the swirling waters about the schooner had discoloured a large patch of the sea.

The long coastline emerged, covered with clouds which wept a light drizzle of tears. Wadawaka managed to alter the course so that the wind took us away from the mud-coloured patch of ocean. As we left its confines, our schooner eased her rolling and she trembled only slightly. ‘Ah, she too wants to rest against the land,’ our chief mate smiled as he let his body move with her vibrations. He eased her towards a point of land which was shaped like the head of a lizard. As we came nearer, the head fattened out into a plump body.

‘Well, we have reached a lizard of an island,’ Wadawaka exclaimed. ‘And there is the tail!’ At the very tip, he swung the wheel to bring us about. Our sail flapped, then tugged us in a different direction. ‘Now let’s see what is on the lee,’ he muttered. ‘Ah, there’s a bay between tail and body, it will be our resting place. Take us there, now girl.’

In obedience, the schooner slid into the bay.

‘Drop the sail, George,’ Wadawaka called. ‘I’ll lash the helm and then let go the anchor.’

Sheltered from the wind, our schooner seemed to sigh as she rode at peace. The light rain continued to fall, making the beach hazy and misty. It was then that Hercules leapt up on deck and gave a shout. Then most of our mob emerged to gaze at the shore. I looked at the woebegone lot. It hadn’t been fun being confined in the womb of the vessel; but the sight of land would quickly revive their spirits. And it did! They had had enough of ships and oceans and quickly unroped the boat which had been lashed to the deck and heaved it over the side. With a boat hook I held her close as Hercules and four men, bulky in their cloaks, gingerly clambered down then rowed off to reconnoitre the beach – although perhaps they might have waited for their shaman, my father Jangamuttuk, to go along with them, for who would negotiate the right of landing if there was another tribe of blackfellows living there. Hercules’ idea of negotiation was to knock out any opposition with his club; but what was a waddy against a spear or musket?

Wadawaka let them go without a word of protest. He had a healthy respect for the physical prowess of Hercules, but none for his mental abilities. Still, concerned about such a dash into the unknown, he lifted his telescope and carefully examined the island. He held it where the land rose up towards a central ridge. Even without the aid of the glass, I could see a small, square log cabin nestling in a hollow. ‘Someone there,’ he said, ‘not blackfellows either. There’s a garden about the hut and what seems to be corn growing. Well, we’ll wait a bit and let Hercules handle it. He’ll either get his fool head blown off, or bash someone’s head in.’

It was then that a musket shot sounded. A darker vapour marked the grey mist of rain in front of the cabin and then a figure came to the doorway. He calmly reloaded his long musket, but kept the butt resting between his legs. He looked at our mob who in turn eyed him. He stayed in his doorway not even bothering to raise his gun. After a few minutes of stalemate, Hercules and the men with him backed to the boat and pushed it off into the surf. They scrambled into it and hastily rowed for the schooner. It seemed that Hercules for once had decided that more than his club was necessary to break the deadlock. Perhaps we needed ghost weapons, I thought, dashing below to find my pistol. I checked its priming, then thrust it in my belt where it was hidden beneath my cloak.

When I came back on deck, I saw the boat pulling alongside and Wadawaka flinging down an armful of spears. I wondered why he hadn’t taken a couple of the muskets we had, but held my peace. Jangamuttuk, my father, now managed to make it up from below. The poor old fellow had suffered dreadfully from seasickness and was still shaky on his pins. Still, he wanted to go ashore and so I held the boat close to our vessel’s side while Wadawaka picked him up and deposited him in it. Even though it was now a tight squeeze, we ourselves then scrambled down. As we rowed towards the shore, each sweep of the oars threatened to swamp our overloaded dinghy.

Still, Wadawaka steadied himself enough to use his telescope. He passed it to me as a wave rose under us. As we rose higher and higher, I held the glass to my eye and trained it on the figure. It was indeed one of those we called ghosts, but clad in rough clothing similar to our own. He wore pants and a jacket made out of kangaroo skins with the fur inside. His grey hair hung lank about a face mostly covered with a grey beard from which a single blue eye gleamed balefully. The other, if he had one, was covered by a black patch. On his head he wore a possum skin which still held the head poking out above his forehead.

Suddenly, the eye piece of the telescope slammed into my eye as the wave broke. The boat shuddered and went under. It struggled up and then grounded. We scrambled out and as we pulled our craft up onto the beach, the ugly ghost shouted: ‘You lot, beware! This is my island and there’s only room enough for me.’ He lifted his long musket and aimed it towards us. This caused us to huddle about the boat, all except for Wadawaka, and Jangamuttuk who had revived once his feet had touched solid earth.

‘We’re coasting westwards,’ Wadawaka shouted, ‘but the wind’s agin us. We have to wait it out here. When it’s for us, we’ll be away. No problems with that, is there?’

‘Well, you are not much welcome,’ the ghost shouted. ‘From the looks of you, you’re not government or free booters such as myself. You got a fine vessel there; but who’s in charge of her? You blackfellows can hardly paddle a canoe, let alone sail a schooner. Where’s your captain? I’ll have a word with him, for I bid you welcome only as long as you keep the peace.’

‘We blackfellows crew and sail this schooner,’ Wadawaka shouted back. ‘You’ve never been to the West Indies where we do all the work, the sailing and the piloting and a right good job we make of it. Far better than some of them whiteskins that now rest on the bottom of the sea. They bandied words about our ability or lack of it.’

‘Well, it’s the first I’ve seen of it along these shores and I’ve been here from the first,’ rejoined the apparition. ‘You lot don’t seem to be West Indians anyways. More likely from that big island to the south east. I know them blackfellows or what remains of them as that’s where I started out, courtesy of Her Majesty’s Government. Anyway, find a spot to camp; but away from my cabin, and mind you leave my garden alone. Hard enough it was to get the seeds and then the plants to grow. There’s enough stealing from bandicoots and the like without you lot helping yourselves to them. Anyway get settled, and when you’ve had a feed of your own grub and got your land legs back, I’ll come down and hear out your tale. Sure enough, it’s indeed a worthy schooner you’ve got there, and run by blackfellows,’ he added, his glowing eye fixed on her. Then with his head nodding, setting the possum head bobbing, he disappeared back into his cabin.

Hercules snarled as the sound came to us of the door being slammed then barred. He stared at the closed door and growled: ‘Who wants to be cooped up with that. They stink and can’t keep their hands off our women. I’ve seen that creep somewheres before and I’ll remember in time. Well, he’ll keep. Let’s find a place to set up camp. I can’t stand this weepy rain that clings to your hair until it gets too heavy, then trickles down your neck.’

‘You find a spot,’ Wadawaka agreed. ‘I’ll go and get one of the spare sails. We don’t need a koorowri, a hut, but only the framework for a wooloa.’

I went with Wadawaka to the boat and helped him to push it into the water and then row out to our vessel. The rest of our mob took themselves ashore while we got the sail, a large pot and tin cups, some of our provisions, flour and salt tack. We stacked them into the boat which was waiting for us with the last of our people.

Back on shore, we found that Hercules had decided to set up camp in a thicket of small trees that grew in a shallow hollow some distance from the cabin. A number of saplings with forked tips had been cut which then had been hammered into the ground upright in a line. In the forks were placed horizontal poles and then others were propped along these at an angle of 45 degrees. We flung the canvas over this and fastened down the back with stones. It made a long open-fronted tent and protected us from the drizzle which still continued to fall. Everything dripped and we wondered where we might find dry kindling to start our fires. I looked across at the ghost’s cabin and at the lean-to stacked with short logs and kindling. The door was still tightly closed and as the only windows were to the front it was easy for me and a couple of others to sneak over and get what we wanted. Soon, we had three fires blazing along the long front of our tent and could feel the warmth against our skins. Now Wadawaka got me to fill the iron pot with water. The ghost had chosen his site well and there was a spring close to the cabin. When I returned, my friend had set up two upright forked sticks on opposite sides of a fire. He took the pot of water from me, put a green piece of wood through the handle and hung it over the fire. He flung in a piece of salt pork, then with a shrug went off to look over the garden. He came back with potatoes, beans and corn cobs which he put into the pot. When it came on the boil he pulled away some of the burning logs so that the stew went down to a simmer. After this he flung in some flour and salt and stirred it.

We were sipping the stew from our tin cups, when my mother Ludjee glanced up and gave a short scream. I grabbed for my pistol as she got to her feet and ran towards two women who had crept out of the thicket and were staring at us.

My mother rushed to the two strangers, stopped in front of them and stared wildly from face to face. Suddenly, the three fell to ahugging and both exclaimed, ‘Ludjee, Ludjee’ over and over again while Mother cried, ‘Nadjee, Lorimee,’ gazing from one to the other. Now all three began laughing and crying. At last they settled and came to the fire where we were sitting. It was then that I heard that these were my mother’s long lost sisters who had been stolen in front of her eyes by a boatload of ghosts, one of whom was the one they were now with. Malone was his name.

Before we had been exiled to the northern island where I had been born, Ludjee and her sisters were living on another island to the west of the mother land. The times were unravelling there as the ghosts had come through to take the mother. The tribe stayed on, waiting and wondering how things would turn out and if the times would ever again become aligned. One day, the three young sisters were sporting in the surf when a whale boat came rowing into the bay. They were used to such watercraft by then and took no notice, continuing their play until it bobbed next to them. ‘Come my pretties,’ one of the ghosts called, holding out a yellow ribbon, which fluttered in the breeze. Ludjee hung back as her two sisters swam to the boat and taking hold of the side with one hand stretched out the other for the gaudy piece of cloth which flapped in the breeze and eluded their grasping hands. It didn’t help that the ghost who held them, kept pulling the ribbons away as they attempted to snatch them. Then before my mother’s horrified eyes, while her sisters were distracted, the two men at the stern suddenly grabbed the hands holding onto the boat and heaved them aboard. The boat rocked alarmingly, but did not capsize. Now the ghosts rowed swiftly out of the bay and that was the last my mother had seen of her sisters until this day.

‘But how come you stay with that ghost?’ she asked them. ‘Haven’t you tried to get away?’

‘He’s better than the one we were with,’ Nadjee replied. ‘He doesn’t hurt us like the first brute who had us. Why we were only little girls and he almost split us in half ...’

‘How come you got to be with this fellow. He looks evil ...’

‘You can’t judge a bloke by his looks you know. You mob for example look a rum lot in your furry skins; but then so do we. We look like great lumpy monsters, so give us another hug before I tell you how we became Malone’s sluts, for that is what they call us.’

Again the three fell to embracing, then Lorimee took up the story. ‘Well,’ she said, ‘When those ghosts kidnapped us, they took us along the coast. They hoisted their sail and coasted along on a breeze until night fell when they put in to shore and made camp. It was then that they began squabbling over us and the brute that laid claim to us decked an even more loathsome one with an oar. It broke off and he jammed the shattered end into the bloke’s throat and leant on it. He guffawed as his mate squirmed and then when he had had enough fun, he jerked the end of the oar out and with it came his life blood. That cowed the others and he got them to bury his victim while he turned to us. They had tied us to a tree with a rope about our necks leaving our legs and hands free. That didn’t do us much good, then he got first Nadjee down, then me. He laughed as our tiny fists punched his face, then his own fist soon put a stop to it. When we came to, the last man was just finishing off with me. I ached and pained all over and all I could hear as he heaved away was Nadjee groaning softly to herself and then I heard someone else sobbing on and on and it was me. They didn’t care if we were sore or bled, and kept at us until we were nigh crippled. If it hadn’t been for Malone, we most likely would have ended up dead. We couldn’t run off as we could barely walk, and later when our bodies had gotten used to the violation and they had eased off, when we did try to escape, they just about flogged the life out of us. You should see our backs.’

Both sisters pulled off their heavy skin jackets and turned their dark backs towards the fire as if to warm them. The flames seemed to reach out through the misty air to gleam off the crisscrosses of white scars that marked the black. There were gasps from us and then sobs and even the sky wept a gentle rain. Ludjee shed tears as she traced out the pattern of torment and murmured: ‘You cannot call them beasts, for never have I met a beast that did such a thing. Surely it is true as those to the north believe that they are moma, devils who lack an affinity with humans.’

‘Yes and we know how they handled their moma, don’t we,’ Hercules growled, not shouting for a change. ‘I was betrothed to Kaddinee. She was only fourteen and I had to wait and while I was waiting they got her. We could not understand their ferocity as we came across first her head which they had left in a fork of a tree to mock us, then her violated body. They had cut off her breasts, though they had had to scrape along the breast bone for she was a mere child, then hammered a stake between her legs. Well, this ghost or moma will pay!’

His head fell onto his knees and he went quiet as death. There was a feeling of impending violence in the air and Wadawaka tried to lessen it by asking if anyone knew that this ghost had mistreated women.

Nadjee scowled and then spat into the fire. ‘He treats us well enough and only now and again makes us go to his mates. It is their way and sometimes when they come and there is a party there is much singing and dancing, and we have a fine time. We are used to it now.’

Lorimee added: ‘Where could we go, if we left him and who would take us in? We have been defiled by them and even those blackfellows on the mainland opposite are frightened of us. So we stay, work for him and sometimes party. It’s not all bad, though. See that garden and that pile of wood, it’s not him that tends the plants or cuts the wood. It’s us. He sits around in that hut of his and dips his pannikin into his rum cask and ...’

‘He trades us for that rum,’ Nadjee exclaimed.

‘He’s not so bad, not like the others,’ Lorimee broke in. ‘It was far worse with them. It was lucky for us when he won us, for strangely he likes a bit of the lash himself though you have to be careful not to hurt him, or else he bellows like a stuck pig.’

‘Won you?!’ Wadawaka exclaimed, as if he was re-living other horrors invoked by the women’s story.

‘Yes at cards. They were using us, all of them, but only that brute owned us. Malone, our ghost, had taken a fancy to both of us. Even then he had thought of settling on this island and “living the life of Riley” as he put it. This meant that he wanted us to do all the work as well as touching him up with the lash every now and again. So, he waited and seized the opportunity when it came. He got the brute drinking and out came the cards and he finally got us with a couple of red queens which he had palmed.’

‘And that’s why he calls us the Queen of Spades and Clubs,’ Nadjee broke in, ‘though he got us with the red, but he says that it was the black that made him lucky and when he gets into a game these days, he rubs our skins for luck. ’

‘To get back to what happened next,’ Lorimee raised her voice above that of her sister, ‘that brute, he let us go just like that, saying that there were more birds in the bush and he only liked to sample them, not own them.’

‘True,’ Nadjee regained the story. ‘Just like that, but that Malone once said that he was off to some place up the coast and didn’t need to be lumbered with two black women.’

‘Well,’ Lorimee said, ‘whatever made him do it, he did it and that was good for us.’

Wadawaka picked up a glowing stick from the fire and flung it out into the darkness. He watched. A tiny flame flickered up, then disappeared. ‘You know,’ he said, ‘it is the same everywhere for us black folks. The whip, the lash, manacles and degradation. It is too much and ...’ Suddenly he broke off, staring hard into the gathering darkness. Such was the intensity of his gaze that we all began looking into the blurred outline of a tree where something, light and indistinct fluttered among the leaves. Then it was gone and all that we could think was that some spirit had been listening to the women’s tale of woe.

Wadawaka, more agitated than he had been when he was speaking, got to his feet and prowled within the illumination of the campfires, stopping every now and again to stare off into the gathering darkness. At least the drizzle had stopped and now as night fell like a heavy blanket, the clouds parted to let the moon peer down. It was a half moon with a halo, surrounded by the brittle sparks of stars. These made me think of the skyworld and the campfires of our ancestors, though then I became frightened as I imagined ghosts as numerous as falling drops of rain flooding down to conquer this world of ours. This was what my father and our shaman had told us and it was under his influence that we had begun our voyage westwards so that we might be free of them once and for all.

I missed my friend and got to my feet. I was about to follow him, for it was not good to leave a person to wander by himself in a strange land, when there was another disturbance as the ghost Malone walked into our camp with a small barrel on his shoulder. He smelt of rancid meat and rum and in the fire and moonlight did indeed appear like some demon. He stopped, jerked his head about and saw my mother’s sisters there.

‘Didn’t I tell you to stay in the bush until I called for you,’ he snarled at them. ‘Just remember who you belong to and what blackfellows think of you for being with me. Queens or traitors, eh? You’re better off here with me than with a bunch of damn savages anyway. So keep yourselves to yourselves and stick by me, or else,’ he threatened.

The two women glanced at each other, then back at their ghost and Nadjee muttered: ‘Why, are you going to whip us?’

They made no attempt to get to their feet and Malone licked his lips as he stared at them before shrugging and muttering: ‘They’re like dogs, you know, like dogs.’ His one good eye gleamed malignantly as it flicked from face to face. ‘Treat ’em with kindness, let ’em sleep at the foot of your bed, throw ’em a few scraps, avoid their sharp teeth if they get stroppy and you got friends for life. Can’t get rid of ’em, you know. Malone’s sluts and they know their master and I could show you how much they can show it ...’ He stopped abruptly with a leer, licking his lips as if he was about to go on, then clamped his mouth shut as if he had just recollected who he was among, a mob of blackfellows, some of whom most likely understood English and might take his words amiss.

He covered what confusion he felt, if any, by setting the cask down carefully, then flopping down next to it. He seemed not to notice that we were all staring at him with hostility and instead pulled out a pannikin, fiddled with the cask until he got the bung out, let his mug fill then shut off the flow and gulped the liquid down. As his face lifted and dropped with the emptying of the mug, I noticed that his possum cap had two red stones in the place of eyes and these stared venomously at me, reminding me of other eyes, of another ghost who had treated me with kindness, if it could be called that. I didn’t like thinking about that and turned my attention to Malone’s one blue eye which was clouded over as if with some filmy tissue, and if the eye beneath the black patch was in similar condition, it meant that he was going blind and needed workers or companions.

Now, drunkenly he muttered something indistinctly, hawked a mass of phlegm up, spat it into the fire where it sizzled a long moment, then spoke again. ‘Well, at least one of you knows the English language and I expect all of you’ll know what the government will do to you, if they catch you with that boat. As far as I know blacks are property and with not as much up in the top storey as we white fellows. You need a white bloke in charge of you, tell you what to do and how to do it. You’ll get by that way and no-one’ll say a word against you. Well, I’m glad to know that you can sail this sort of boat, I can’t, but what's the use of sailing her if you can’t put into a port. As I’ve said, what you need is a white man in charge, then bob’s your uncle. Look at me, I’m that white bloke and what’s more I’ve got a load of kangaroo skins waiting to be taken and sold. You’ve got the boat and I’ve got the colour. A fair swap if you ask me. Nothing else to say, except let’s celebrate your new captain and he’s a kind master as long as you don’t get in his way. Ask the queens there. I’m a good bloke. Never laid a finger on them though they’ve deserved it more than once and sometimes, you know, I need a bit of a massage and they go at it too hard just out of spite. Well, that’s neither here nor there. So what do you say, eh? There’s nothing but desert to the west of us, best if we load up the skins, go east then north to sell ’em at Port Jackson.’

Hercules gave a snarl which if the ghost had known him would have put him on guard. He didn’t, nor did he heed the fact that the giant had been dangerously silent. When Hercules was like that it was best to get him talking, but Malone ignored him and we weren’t butting in to warn him. Now the ghost swung his filmy eye over us as he babbled on. ‘Of course, we’ll have to get ourselves presentable. Get you and me cleaned up. When you got a vessel like this, you got to look the part, swank it up a bit.’

He gulped his rum and it was then that Hercules lumbered to his feet and went out of the firelight. I thought that he was going for a piss and this got me wondering about our missing chief mate. What would he make of the ghost’s idea? It was an easy answer. He would think it shit. It was then that Hercules returned. He took two large steps as he came into the firelight and stood in front of the ghost. His arm swung back, then down. The axe which he had taken from Malone’s woodpile flashed down, through the possum skin cap and then the brain, cleaving the skull in twain as it lodged up against the top of the spine. Bits of bone and grey matter splattered over us. The women shrieked and the two sisters rushed to the dead ghost and began wailing: ‘He wasn’t that bad; he wasn’t that bad,’ they cried over and over again.

In fascination I watched the blood gush from the split skull. How red and intoxicating it looked. I felt like rushing in and lapping it up. I was on my feet ready to go to the dying ghost and press my mouth over his red gaping wound, when I got ahold of myself. Murder had been done and where was my father, Jangamuttuk. Where was Wadawaka? In a panic I rushed away to find them, for they would know what to do.