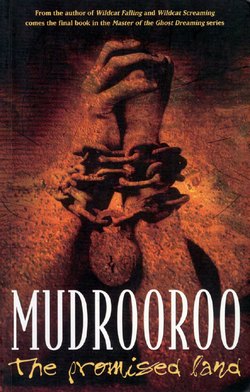

Читать книгу The Promised Land - Mudrooroo - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеOnce, the governor and his lady wife had added the bon to the ton; but that was years ago in the metropolis. In his scarlet jacket and plumed hat, Colonel Crawley, Governor of Westland, still looked resplendent, at least from. a distance. When one came closer, the shabbiness of his furnishments became apparent, though one had to admit that he looked a fine figure, as did his wife. Rebecca was costumed in a fine day dress and a bonnet with a profusion of flowers; but her apparel, even to a casual glance, had seen better days, as had the wearer of them. The bon had long deserted the ton.

Still, they stood upright and seemingly self-possessed as the detachment of native police in their kepis, dark coats with silver buttons and shining boots trotted behind Sir George’s bughi, which (newer and better equipped than the governor himself, not to mention his carriage) approached them. Sir George, clad in a dark frock coat and with his head bare, though beside him rested a wide-brimmed planter’s straw hat, held the reins loosely and kept his eyes fixed ahead. Beside him was the heavily draped figure of Mrs Fraser. As her face was completely veiled, it was impossible to see the direction of her gaze; but a slim spectator, clad in the whitest of flimsy white, had no doubt that Amelia’s eyes were on her. Lucy fluttered a hand in loss, and drooped like a daisy under a warm breeze as the vehicle passed. Now she let her glance linger on the native police troop, headed by a solitary white man whose stout figure bounced in a somewhat ungainly fashion on his mount, though the fierce florid face with its sweeping salt-and-pepper moustache was enough to quell any criticism. He was an old soldier from the ranks who had fought at Waterloo in the infantry, and had come to his position only after a lifetime of active service.

Sergeant Barron was as proud of his native recruits as he had been of his regiment. As he came abreast of the governor he shouted out: ‘Eyes right!’ The black policemen obeyed the command in perfect unison. The governor grunted in appreciation and then waited for the eight heavily laden drays to roll past. Each was driven by a police trooper who had tethered his horse behind. The line was long, but eventually it cleared the town and headed for a gap in the escarpment which led up to the flat inland plateau.

The expedition was to have had an early start, but punctuality was not part of colonial life. In fact, once, some time ago, the clocks had all run down and they had been without time until the next ship arrived. Time was flexible and, what with one thing or another, it was noon by the time the expedition had assembled. Then there was a wait for the governor to arrive, and after that they had passed in review and trundled from the town along a rough rutted track which was considered a high road. This meandered through the coastal plain and then up a rise leading to the pass onto the flat inland plateau. At the head of the pass, Sir George stood up in the bughi and held up his hand to halt the line of vehicles behind him. He cast his eyes about, examining the country and finding not much to observe. The land was flat and featureless, the melancholy rutted track disappearing into the eastern horizon.

He motioned the column forward then sat with a thump and shook the reins. They proceeded along the track and continued on until, as the sun was sinking, he decided it was the appropriate time to camp. He summoned the commander of the police to him and gave the necessary order. It was then that Sergeant Barron came into his element, shouting at some of his men to unharness and unsaddle the horses, then hobble them before turning them loose to forage for what grass there was. The remainder he ordered to set up camp, pitching the tents in a single row, at the head of which was his own and a short distance away those of the two civilians. By that time the mess had been set up and the native cook had his fire blazing while he prepared the food.

Sergeant Barron, when he had everything as he liked it, well ordered and spick and span, strode to where Sir George was sitting in his canvas folding chair, removed his kepi and lowered his voice to a rough growl as he said: ‘Would have liked to have got a bit further along, but the late start kiboshed it. Tomorrow, up at the crack of dawn and on the road by sun up. With that, we’ll make the waterhole; at least, so Monaitch assures me and what he says agrees with Bailey’s chart.’

‘Ah, yes, the Bailey expedition guide,’ Sir George replied. ‘I must have a word with him. I have heard that he is a convert.’

‘He is and it’s to the good and to the bad. Ready to obey a command, but his Jesus that and his Jesus this gets a mite overbearing, if you get my meaning.’

Sergeant Barron was about to add more to this effect, when he stopped, for his listener’s face had turned purple. Sir George’s voice shrilled as he retorted: ‘No, Sergeant, the meaning I get is good news indeed. In my time I have been a lay preacher, and the Word of God is not to be despised, nor are those who open themselves to our Lord and Master, Jesus, the very Son of God who came down to save each and all of us.’

‘Well, I’ll add my amen to all that, sir. I’ll send him along directly after we have eaten. Perhaps you can share a hymn or two,’ Barron replied, with a carefully neutral expression to which the knight could not take exception. The police sergeant turned to go, then looked over his shoulder and said: ‘Take it you’re prepared to eat police grub. Got one of my boys trained in what you might call the culinary arts. His food is basic, but filling. I’ll send over a plate for you and the lady.’

Sir George nodded, falling into the romantic past of his previous journeys, and when the plate of salt pork and beans was placed before him he ate with a gusto he had not felt for some time. He had invited Mrs Fraser to share his humble repast but did not notice that she merely pushed her food about on the plate, then fed it to her canine companion before excusing herself and going into her tent. She emerged with her drawing pad and quickly sketched the camp scene. There in the foreground sat Sir George in his canvas collapsible chair.

‘Ah, the first record,’ he said, eyeing the sketch, and then suggested that she might do another in a little while when he was communicating with the native constables. He wanted it when the sun was setting and long shadows streaking across the campsite. ‘Put in a tree or two, for I see that there is none that will give me the effect I desire.’ She nodded to this and, when the time came, followed him to Sergeant Barron who shouted as they approached: ‘Monaitch, on the double!’

A native clad in ragged shirt and canvas trousers ran towards them.

‘Civilian black, sir. Not one of mine at all and not eligible for a police issue of clothing,’ the police sergeant explained. Then, angry at such raggedness and shabbiness, he growled: ‘If the blighter put in a day or two’s work, what with everyone off to the diggings, he might dress like a king. Get them to ride or shoot all right, but an honest day’s labour, not on your nelly.’

‘All right, Sergeant, that will be enough.’ Sir George scowled as he added: ‘And he is working now, as my guide, and what’s more he is a Christian and when the occasion arises, I myself shall clothe him.’

‘Very good,’ Barron replied, his face carefully blank.

Monaitch stood before Sir George clutching a Bible. Proudly, he held it out towards the knight. ‘I carry Word of God,’ he intoned. ‘I cannot read, for he who was about to teach me was murdered by those who refused to accept Jesus as their Lord and Saviour. Fools, for they are perdition bound. Please, read me chapter and verse, for I hear you are Christian man. Good Christian man, yes? How uplifting, yes, a holy journey, undertaken in furtherance of His work.’

‘Yes, yes,’ answered Sir George, who once had been called Father by the remnants of a savage people he had instructed in the arts of civilisation and the true religion. He sought to summon up his reserves of piety, but those quaint years of being a father to savages who had ill repaid his efforts were long gone and he had other concerns to pursue now, even though he was ostensibly on a mission of mercy. The old image he now tried to invoke was for Mrs Fraser and her ready sketch pad.

‘I will preach to all of them,’ he declared, turning to her. ‘It will be a good picture, the light dawning in their dusky faces as I exhort them to forgo their cruel savagery.’

‘They’ve already done that. Good boys now, the lot of them,’ Sergeant Barron commented, defending his men.

‘But do they accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Saviour?’ Sir George replied testily, staring at the soldier who, for all he knew, could be as much in need of saving as any of the blackfellows under him.

‘That I wouldn’t know, but they accept me as their chief and the police as their new tribe,’ rejoined the sergeant. ‘That is what the governor wanted me to do and I did it. They’re loyal now and true to their uniform and me –’

‘Jesus alone is my Lord and Saviour,’ Monaitch intoned, breaking in to end the policeman’s words. He knelt and rattled off in a sing-song voice: ‘Therefore, accursed Devil, acknowledge your condemnation, and pay homage to the living and true God; pay homage to Jesus Christ, His son, and to the Holy Spirit, and depart from these servants of God, for Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, has called them to His holy grace. Accursed Devil, never dare to desecrate the holy sign of the cross. Through the same Christ our Lord, who is to come to judge the living and the dead and the world by fire.’

‘Amen, amen,’ called Sir George, shrilly. For some reason, he felt himself disliking the sentiment expressed, and this caused him to wonder from which sect the missionary had come. Still, he felt pleasure in having a convert of such fervour kneeling at his feet and clasping in both hands the cross he wore on a string about his neck. He looked around to see if Mrs Fraser was sketching this touching scene and was disappointed to find that she had disappeared. Well, she could copy it from memory.

Now, with his hand uplifted, he said, ‘Rise, my son,’ and then began to sing:

‘Speed Thy servants, Saviour, speed them!

Thou art Lord of winds and waves:

They were bound, but Thou shall free them;

Now they go to free the slaves.

Be Thou with them:

’Tis Thine arm alone that saves.

Friends, and home, and all forsaking,

Lord, we go at Thy command;

As our state Thy promise taking

While we traverse sea and land:

O be with us!

Lead us safely by the hand.’

‘Amen, amen, amen, amen!’ shouted the ecstatic Monaitch; but Sir George suddenly felt despondency sweeping over him. Once, he too had radiated such fervour, though into an unresponsive world that over the years had lessened his urges for such enthusiasms. How he longed for that more youthful time and faith, which had powered him through trackless wildernesses seeking out such as those who stood before him. ‘Hallelujah, hallelujah,’ he had shouted in exultation and those, his children, had shouted back: ‘Jesu, Jesu.’ Then, then, on fire, but now his heart held only ashes and his mind only greed for the pure gold. Gold, yes, gold, the soft glowing metal cheered him as well as fevered him. He breathed in deeply and felt that the dust particles in the air were gold, filling him with their power. Now he was ready. He took up the Bible, let it open at a page and read:

‘“At that time, as the eleven disciples were at table, Jesus was revealed to them. He reproached them for their disbelief and stubbornness, since they had put no faith in those who had seen him after he had been raised. And he told them, ‘Go into the whole world and proclaim the good news to the whole of creation. The man who believes in it and accepts baptism will be saved; the man who refuses to belief in it will be condemned. And signs like these will accompany those who have professed their faith: they will use my name to expel demons; they will speak entirely new languages; they will be able to handle serpents; they will even be able to drink deadly poison without harm; and the sick upon whom they lay their hands will recover.”’

‘O Lord, you glow before me like molten gold!’ he suddenly shouted, glaring at his flock who, perhaps luckily, were not his flock. They stared back at him ·in puzzlement and he wished to move them as his bright vision had him. His mind returned to the old days and the words of a simple sermon came to him. He began to speak as if in tongues. It was broken English and he pushed his voice up to a shrill to reach into the hearts of each and every one who was listening. ‘One good God; one bad Devil. God good to us. He lives in sky and looks down. Devil is bad and lives underground in the fire. Good people who love God will go to Him when they die. All those go along same road, white man and blackfellow. True, true!’

Sir George stopped, for the troopers were staring back at him with blank faces which did not reveal even limited interest in his words. Their leader had a different expression on his face, though he spoke kindly enough: ‘Sir, these heathen need someone to instruct them carefully. They know only my commands and what I teach them. Later, they will learn more when missionaries are sent among them. Your words only confuse them. It’ll take a while yet, before they are ready for such sermons.’

‘Hallelujah,’ the irrepressible Monaitch shouted. ‘Good, Father, good. Hallelujah!’

‘If there is only one prepared to listen, then that is enough; for it is not the size of the congregation that matters, but the faith in their hearts.’ And with this Sir George took the arm of the convert. He guided Monaitch to his tent where he talked to him not of God and Jesus, but of the stone streaked with yellow marks which the Bailey expedition had found. ‘I need to know about this magic stone if I am to further God’s work,’ he said, appealing to both the Christian and the savage in Monaitch.

The native screwed up his face. Sir George watched him ponder, then smile. Monaitch laughed in glee as he replied: ‘That stone, not magic, but pretty. I found it, liked it and flung it into a dray. No one cared for it, not even that governor. Later, they want to know where it come from. True, true, silly stone. Well, my words not so many then and I mistook their question. I said “Yillarn”, which means in our language “rock”, and there is a place of that name too where Bailey been. But it not come from there. It come from Kalipa, a place in desert where they live without Jesus.’

‘Are there many such stones there, Monaitch?’ Sir George asked, placing his hand on the man’s shoulder. In his experience, such physical contact was welcomed by blackfellows.

‘Many, many, enough to build a big house for God.’

‘And I will too, that is a promise to you,’ declared Sir George. ‘So you know this place?’

‘I know this place. Jesus show me the way. He talk to me, He talk to me. He does, He does,’ the native shouted.

‘He does, I assure you He does,’ the knight replied, rubbing his hands together. ‘And you can lead us there?’

‘Too right I can. Hallelujah, Father, Hallelujah, for the tribe there know not the Lord. He not their Saviour. They believe in giant serpent. Kill it, kill it, for Jesus’ sake.’

‘The Devil, yes, that is the Devil and he must be unthroned. Monaitch, the Lord has smiled down on you this day.’

When the native guide lifted up his cross, Amelia Fraser, who was preparing to sketch the scene, slipped quickly away from the detested symbol which shone a lurid painful light that blistered her skin. Sir George’s words about driving out demons might have made her smile at other times, but the symbol of another’s pain had hurt her enough to make her rage that there were such things of torment. The sun dipped below the horizon as she rushed into her tent. At last! She flung off her heavy and constricting clothing, which again reminded her of her mortality, then she transformed into a bat and flapped up into the sky. Her anger left her and she exulted in her mastery of the elements, though she had to keep close to the ground until the sun was well and truly gone and night was a warm refuge about her. Now she rose higher and higher until the land spread out below her as wide and as enduring and as lonesome as her life felt; but she had a friend. She flew a large circle and to the east saw a single dot of red which might be a campfire; but as she completed the arc to the southwest the small collection of lights which marked the town drew her. She darted off towards it.

Except for the drawing room and Lucy’s bedchamber, the governor’s bungalow was in darkness with nary a figure in sight. Still, Amelia carefully circled the structure before coming down to the lighted window of the girl’s room. She fluttered there, beating her wings and hoping to attract her attention. She stopped this when she saw that her friend was not alone. She was conversing with Rebecca Crawley, or rather listening to her. Amelia hung at the window and waited.

The bedchamber, as all the rooms, was overcrowded with furniture. A four-poster bed was pressed against one wall, a dressing table filled a gap between the head of the bed, and a huge mahogany dresser hulked along the wall, covering the bottom half of the window. Against the other wall, leaving scarcely room for the door to open, was a large wardrobe in which Lucy had stacked her husband’s and her own clothing in an attempt to keep them from the dust which covered everything. Alongside the bed an Axminster carpet had been laid out. On it were three stuffed easy chairs and pieces of luggage which made the space into an irregular maze.

Lucy sat on the bed, which was perhaps the only comfortable and free place in the room, for the chairs were piled with odds and ends. It also provided enough space for the wooden frame of her embroidery tapestry which was before her though the canvas was still blank. The governor’s lady shared her bed, reclining on it and taking up much more space than the girl, who was forced to huddle against the bedhead.

Rebecca Crawley with only Lucy as a guest had stopped any pretence of dressing appropriately for morning, noon and evening. She wore a pink domino, more than a trifle faded and soiled, and marked here and there with pomatum; but her arms shone out from the loose sleeves of the garment, which was tied tightly around her waist so as to set off her still trim figure. As she reclined on one elbow, she sipped on a glass of brandy, thus breaking up into paragraphs the monologue bemoaning her fate.

‘Is not this a strange and dismal place for a woman who has lived in a vastly superior world? Was it my fault that I put the interests of my country first and, I admit it, was naive enough to be led on by my Lord Steyne? Politics, my dear, is not for us women, and so alas and to my detriment what was to have been discreet became indiscreet and the subject of vain journalists who slung low jibes in my direction. Calumnies, but they hurt, my dear, they hurt as if I was being struck by arrows and I was too, arrows of outrageous fortune. I, who but followed the dictates of my husband, had to continue to do so when he was shunted off to this post.’

She took a sip of brandy and passed one of Lucy’s lace handkerchiefs across her eyes.

‘But, alas, it is the lot of women to be alongside their men and I am the truest wife that ever lived. When he was made governor here, I accompanied him, though my heart bled to leave my child, my one darling boy behind; but it was for his own benefit. If he had come with me, he might have become as low as any of these savages. Still, I am as true a mother as I am a wife, and my heart bleeds for him.’

She affected to break down and her sobs filled the handkerchief, though behind the concealing cloth her eyes remained dry.

‘O you poor thing,’ Lucy declared, ‘to be far from hearth and home and the sight of your dear child. I pity you. I couldn’t bear it. I have not your strength and devotion.’

‘And do not forget the luxuriant salons I frequented. I was in the highest of high, society, kings and princes and ambassadors were at my feet. Alas, to be denied all that; but, my dear, I admit it – I have always been restless and if I am here today, then tomorrow I shall be back among those who are my equals. It will be soon too,’ she declared with a tinkle of silvery laughter.

She had another swallow and changed the subject as her mood shifted. ‘And you are going to fill in your days with embroidery. Ah, the delicate work I once did and displayed to great appreciation. Pretty pictures of my ancestral home, but I shall not bore you this night with that. I must go to my dear husband.’ And taking her now empty glass she wound from bed to door and disappeared with a ‘Sweet dreams await you’.

Lucy looked after her and shrugged, turning her attention to her blank canvas. She had failed to get her friend to sketch in a topic and she had not the skill. She knew it; she knew it, and what would she now do to fill in her days? She sighed and fiddled with her wool, then gave a start as from the halfblocked-up window, there came a flapping sound somewhat like a gentle rapping. She tried to lean over the sideboard to peer through. Only the darkness of the night. She sighed again and then suddenly there came again that rapping, but this time it was a gentle tapping at her chamber door. She made a moue. Not that old Rebecca Crawley again with her endless sad stories of a once bright life turned as dismal as the colony to which she had been exiled. She could relate to the poor woman, but it did become tiresome to listen on and on. Maybe she should help herself to her husband’s brandy and dull the next monologue with it. Again that soft rapping. She meandered her way through the chairs and luggage to the door and opened it to her delight.

‘Amelia,’ she gasped as the naked woman slipped into her room and into her arms. ‘You knew that I was feeling peevish and so came to me. Let me hug you some more. I was languishing, thinking you were far out on that – that trail, as that American I once met persisted in saying, although we had regular roads and streets where we lived.’

‘Enough, sweet child. I missed you and could not leave you moping here or me moping there. How dusty and tawdry this place is ... as dusty and as melancholic as the land. Perhaps I have been here too long?’

‘What, you just arrived! I won’t let you leave after only a hug. If this is all that you have for me, you should have brought your dog. I shiver when I imagine his tongue on and in me, and I a young wife too.’

‘Silly, sweet, I meant this land; this end of the earth place. I’ll be with you for a little while.’

‘Well, it is the ends of the world.’

‘It is; but we have each other,’ smiled Amelia, manoeuvring Lucy towards the bed.

‘Wait, Mela – can I call you that? Once I had a good friend, a chum called Mina, and she was somewhat like you, though not as much fun. Wait until I am free of my clothing. Help me! I don’t want to spot it and I doubt that that woman will be back this night, for she seemed somewhat tipsy. She has a thirst for the brandy.’

‘And your Mela has a thirst for you,’ replied the woman, unlacing her, then thrusting her down upon the bed and pressing her lips hard against her neck. She kissed the pulsating vein, then thrust her fangs into it. The iron taste of fresh young blood overwhelmed her senses for a long moment, but only until she felt Lucy’s throat tighten to emit a shriek. Quickly, she put her hand over the girl’s mouth and nose, cutting off her air supply. Lucy’s body began bucking as she fought to get air; but Mela, with the hunger on her, continued to deny her blessed relief while she drank up her blood. With the girl slipping away from consciousness, she finally released her.

Lucy lay there shuddering all over. It was as if she had passed through a little death and found that she still endured. At last, her breathing and body settled. Languidly, she turned and pressed herself against her friend’s naked body. It was so cool and drew away her own warmth. Timidly, her hand went down past Mela’s belly and her fingers brushed her pubic hair. ‘You are dry and arid there,’ Lucy murmured, ‘and I have not the strength to arouse you. Mina used to like my hand doing this to her, but she was so moist.’

‘Well, the land out there is dry and arid, and I have only supped on you a little this night. Next time, you shall find me as drenched as you may wish. Now I should be off, for I must get back before the dawn. It was only your sweet self that called me here, and that red foam I find so delicious.’

‘But, but you will be back soon, Mela? I swear that I need you more than anything.’

‘As soon as it is possible, for the taking of your vital fluid will weaken you. Just build yourself up for my next visit and don’t fret. Occupy your days with that embroidery.’

‘Well, what am I to do if you are not here? Rub myself raw?’ pouted the girl. ‘Go away, leave me to mournful solitude. I have decided to be Clotho, the youngest Fate, and embroider a tapestry with scenes that depict your adventures while I suffer alone here. Go away. There is my canvas and there is my wool; they shall be my friends. But wait, I have no picture.’

‘Silly, silly goose, you mix up the stories ... and as for that blank canvas. Give it here.’

‘See, it is as blank as your heart; and if I mix up the stories, it is because you mix me up. O let me be that other Fate, the third, Atropos who cuts the thread that ends a life. I need you too much to live on alone.’

‘Be like Penelope and embroider while you wait.’

‘O enough of these silly stories. You will go and I shall cry and then I shall embroider. Leave me something that I may begin. When my needles pierce it through and through, I will imagine your teeth at my neck.’

‘Give me the canvas, the night is seeping away. There! This is how the journey began. That is the governor and his wife. Saint George sits in his bughi and a native constable on that dray. It is enough, for that corner. The rest I will sketch in as we go along and I visit you.’

‘But where are you? I want you more than them. Your pale hair, your glowing fair face, your azure eyes tinged with the red of the sunset. I want you as you are now, naked and unashamed and flushed with my blood.’

‘Let it be, my sweet one; let it be! See in that tree? What is that which hangs there with strange reddened eyes that peer out at the scene?’

‘It is a bat. I want you there, Mela!’

‘But let that be me, and I’ll figure too in the other pictures I shall draw for you. Now I must hasten; but before I go I’ll do another scene. There is Saint George, it is but a joke of mine. There is your husband playing the preacher in front of his flock; but where he should clasp a Bible he holds a golden nugget. There, that is your next tapestry scene done. You shall have more as we go along, and when you think of me, look to the picture in which I shall be hidden.’

‘Is that you in the darkened sky, obscuring a star?’

‘It is, and that is where I soon shall be. Hug me now and I’ll lick away the blood which still drips from your lacerated neck ... Now farewell. Ah, you taste so very sweet, like a peppermint. I could easily suck you all away; but, no, there are others. Sweet dreams and in them I shall come to you all moist.’