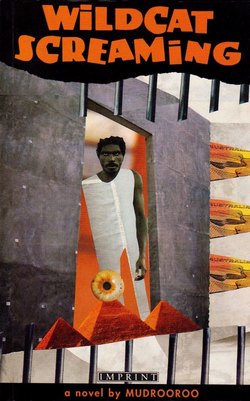

Читать книгу Wildcat Screaming - Mudrooroo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. Back Again

ОглавлениеWell, I can dream can’t I? Dream ?—nightmares, more like it. All I have to do is dream, dream, scream ... I’m now walking through this posh suburb, walking?—more like slinking. Wildcat on the prowl. Naw, though maybe checking out the streets for a bust. Eyes dart this way, that way, all ways, focus, man, on the main chance. Take it and break it real good; but are there any chances left? Not with my luck! Yeah, it’s like that! And then this kid, this tiny kid with mum in tow oozing milk outa her breasts so that I can smell it and all anxious loving eyes, but not for me, comes outa this nice neat home and across the nice neat closely cropped green lawn, smooth as a snooker table. And they come onto the nice clean pavement, littered only with this slinking black cat, who has no business being there except to raid their neat rubbish bins with their garbage all wrapped up and sprayed so that it’ll smell good as that woman oozing her milky smell, though not for me.

The kid catches her distaste, she ain’t ever going to give me a saucer full, and picks up a pebble and with all the viciousness that kids are capable of, flings it at me. It hits me on the right leg, shin bone, and I look down at the instantly formed scar, still hurting like her glance, like her milky smell, and I stare at that kid with murder in my eyes, and snarl: ‘You rotten little brat, just wait till I get hold of you.’ I drag my leg towards him and the white lady, the mum becomes all hot and bothered, she flushes red. ‘Yo! I gotta have protection in this world,’ I begin; but she isn’t listening. Her milky smell turns sour; her eyes incandescent with morality turn, spitting fire and fury at me. ‘He’s only a child,’ she says.

‘Ain’t we all, lady, and I’m going to get that fucker ...’ and just then the leg collapses under me and I’m down on my hands and knees, belly down flat on the ground, ears laid back and tail droopy. Just a pussy cat. Nice looking one though, but she won’t take me in; not even a sour saucer of milk for me. Another stone lands on my back and I scoot away. The lady laughs and says: ‘You aren’t no child, you’re just an animal and should be locked up ...’

Well lady, you’ve got your wish. This so-called menace to society is not going to slink around your nice clean lives for a long, long spell. They’re, you’re going to lock him up ...

So much for dreams and nightmares, screams and accusations. Now I’m suffering just for being alive and not doing so well outa it. Just sitting here with my arm hurting like blazes and my mind hurting like blazes, and there’s a scream sounding and resounding in my head. Shake it, sound tremolos, screeches to a new height, cuts out. Blessed silence; but, man, I’m more than depressed. Depression you can wear, dig? But this is more than that. Like all those sad songs you bought from the jukebox ganging up on you and dragging at your guts. That’s how I’m feeling. Got the ‘Who’s Sorry Now Blues’, and I’m huddling there filled with all that painful feeling, when this old digger with the scabby face, you know, the old red and peeling one of a true rummy, enters my misery and goes into this spiel. Yeah, man. I listen, got to get my mind off my troubles, off the misery in my guts, off the pain from that arm. The right one, because the cops in their infinite wisdom forgot that I was left-handed when they broke it. Stupid cunstables!

‘I was at the Cove,’ says the old codger. ‘9th Battalion, 1st Company under Red Ryder. Anzac Cove, went in on the first boat, and guess what?’ he asks.

‘Well, guess what?’ I fling back at him.

‘We hit the wrong bloody spot and get just this far up that bleeding beach. Red Ryder said “all over”, but it was the wrong bloody beach and we get just this far over,’ he replies, moving a space between his two trembling hands.

‘Well, my great-grandfather was at the battle of Pinjarra,’ I retort, not being provocative, but sorta to put him in his silly old place, though what battle was it when they came up on us, men, women and children and shot us down making us no tomorrow ...

‘Never heard of that one, mate,’ he replies, his ears pricking up as if to appropriate it for later use; and I think would Jacko Turk understand this thing they done to us?

‘Yeah, it’s when you blokes murdered a lot of us Nyoongahs, men, women and children,’ and I smile (if looks could kill) at him as he switches off like a good soldier hearing the word ‘volunteer’.

‘I was at the Cove,’ he begins again, and I can’t help thinking that he’s evading the issue of my smile. He repeats again, adding detail for my delectation. ‘I was at the Cove,’ he repeats adding detail as if it meant something to me. ‘I was at the Cove,’ he repeats, as if it’ll mean more to me by repetition. ‘Ever been in a big mob of ships?’ He goes on, ‘Ever been amongst a big mob of men waiting and thinking while they order you here and there and back again? It was like that, nice peaceful night with the orders shouting up at the starry sky and they push us into those boats. Thirty or forty to a boat, squashed in like sardines, mashed together like bully beef. Little steamboat come puffing up, lines are thrown, linking us up, three boats to that little tug, and then we are off to God knows where. The land humps on the horizon, but as we are just out from Gyppoland we know it ain’t France. We hang in there, not muttering a word ‘cause we are ordered not to. Dark and peaceful, just before dawn. But, cobber, what I remember still is a bloody great flare coming out of the funnel of that tug. It scares the shit outa us, but you know, there is worse to come ...’

‘Worse to come,’ I mutter. There is worse to come, yeah.

‘Worse,’ he repeats. ‘Know what happens to poor diggers, like me? Discarded, like you Abos,’ he whines. ‘What use are we when the fighting’s done? Cannon fodder, mate, that’s us.’

‘Well, you shouldn’t go waving that gun of yours around,’ I sneer, for he’s a flasher as well as a rummy.

‘But, you know what,’ he goes on with that one-groove mind of his, ‘can take this place standing on me head. Army life, cobber, army life is just like boob. What can they throw at you after you’ve had the sergeant major dressing you down, up, sideways and back, you tell me that?’

‘Yeah, it’ll be just like those good old days again, won’t it? That sergeant major of yours is now a screw, ain’t he?’

‘Yeah, but he wasn’t at· the Cove,’ the silly old bugger says, just as if the arm of the gramophone has been lifted up and the needle set at the beginning of the platter again. And I sit there letting him gas on. He’s definitely not a ‘gas’, nor does he even begin to take my mind off my aching arm and woes.

You see I too have been at ‘the Cove’ so as to speak. With my rifle in my hand and all that shit. Another kid on the warpath and it’s led me back again to here. Just a boy giving it all away at nineteen. Had a kiss and a feel at least. Gotta remember that, for it’ll be all I’m having for a long, long spell. Man, I’m buggered. Buggered myself, but you tell me, what I was supposed to do? Join the army and fight in Korea, then come back and be just like this silly old sod? What’s the use? My arm’s hurting, okay; and I’m feeling sorry for myself, well okay, all right! See, I’m in this courthouse cell, just waiting to be sentenced and it’s got to be a long one. They going to throw away the key, mate, I shot a copper, and you just don’t do that in West Aussie or any other state of the Federation. They don’t like it, witness my broken arm. They done that after the kicking I got. This big copper takes out his baton real slow and real deliberately. He stands there rubbing his hand slowly up its length as if it was his prick, though it’s black and hard, not white and flabby like his’un. Then he lifts it and strikes out at my head. I raise my arm and bingo, my arm falls by itself.

‘Jesus, you’ve broken his arm, Mick,’ the copper who’s just put in the boot says.

‘Meant it to be his flaming head,’ the cunstable retorts. His arm coming back for another blow, then stopping in mid-air, since he can’t do two things at the same time, and he’s still talking. ‘Black bastards like him’s gotta be taught a lesson.’

Well, all this time, I’m huddled there quaking and shaking and then the blow comes and I fly out like a light to a place where those coppers can’t follow me. Hospital for a couple of days sure done me the world of good. They could’ve killed me those bastards, and all because I nicked one on the arm. Rotten shot that. Perhaps I should’ve got into the army and learnt to shoot straight. Naw, with my rotten luck, I’d be minus a leg or an arm now ...

‘Jacko Turk ... well, it was bayonet to bayonet. The cold steel, cobber ...’

‘And the cold chill, bloke,’ I answer, listening on as he details his exploits on the field of honour, then switching off to flash back on my own particular exploit, which should’ve come off. It should have; but this cat ain’t got any luck but foul.

It was after that rage rising from being with those snotty University bods and not digging it one bit, that I flashed along the sweet beckoning light towards my particular den of crime, or as the magistrate described it when I was young enough to go before a magistrate and not the hanging judge: ‘a bleeding ground of crime’. They have a way with words, don’t they? I couldn’t resist changing that adjective. It sounds better. We are the bleeding ground of crime. So I float in there, and meet this mate, who later only got a year for the bust and the car, while they wait, are waiting to launch the big one at the copper-shooter-upper — me!

Well, I’m getting a little ahead of myself, though still in the past. Let’s get back to floating along that light beam. Wildcat with his eyes dazzled by the light while thoughts flash in to his brain. I decide that the state has nothing to offer me, and that my chances, whatever they might be, will be better served in the east. Big place that. The mystic east of Sydney and Melbourne where the lights are always beaming out a welcome to me. Blokes tell me the trains stay only a second at the station and if you don’t leap on, you get left behind like a stupid hick, and those trains are electric and in Sydney they got a subway. Wow, man! But to get there I have to get together the necessary cash, and where else to plan to get some than in that bleeding ground of crime. So natter to my mate and the upcome is we nick this car and zoom off into the night with the radio blaring out some of that young rock’n’roll, the blacker the better. Little Richard, Fats Domino, Tee-Bone Walker, the great Chuck Willis. My kinda music. Rebel music. Revenge music, sounding loud though not often on the radio in this stolen car whizzing me back to my home town to get loot for the mythical east. Christ, gotta get my grammar right, maybe. I’m in boob and all those long hours in your cell go quicker if you have your face in a book. Even read The Modern World Encyclopedia, 1935 edition. Real up to date. Look up Australia and us mob. Man, it gives you something to be depressed about. Cold bloody bastards these white blokes. ‘Aboriginal Race. The survivors of the primitive inhabitants are found chiefly in the N. and do not exceed 60,000 in number; they are a declining race. Like the flora and fauna, they represent an archaic survival; they are perhaps related to the ancient Malayo-Indonesian race: they are dark brown in colour, with black wavy hair and a retreating forehead ...’

So it goes on like that, and guess what I’ve got dark wavy hair, though I’m just brown because a white bloke got his wick in somewhere along the line. And you notice that they don’t tell you anything about why us’uns are declining and surviving. Well, my great-grandfather was at the battle of Pinjarra and he survived that along with just a few others. And here I am too surviving just with this aching arm and this old digger telling how he’s been surviving in the First World War. Silly old prick!

'Well, Cap’n Red Ryder, he takes one look at that cove and shouts: “Christ, they landed us in the bloody wrong place. Come on, lads, come on.” Not a shot comes at us as we fix bayonets and charge across the beach and to a rise. We reach it and that’s when the bullets begin. They go “peep-peep” as we charge through the scrub and blunder along. We hope the Cap’n knows where he’s going, for sure as hell we don’t ...’

‘Amen, mate,’ I break in, ‘guess it’s better here. At least we know where we’re bound for.’ You can’t stop the record once it’s started, and he ignores my comment and I fall back into my thoughts and seek to find the place where I’m at. I don’t work like a book. My mind’s here, there and right now back in my little home town, that’s if us Nyoongahs have a home town. Well, just say that I was raised there. Yes, I was and had a mum and sisters and brothers for part of the time, a few uncles, but never can recall any dad. Well, that’s how things are. Now, let’s get on with the story. Let it flow easy, let it flow slow, huh, Wildcat do your strutting.

We cruise into town, down that main street real slow, taking it easy, and pull up in a side street near the store I hold in my mind. Now it’s here. Action! There’s a yard behind filled with petrol and oil drums. Over the gate we go. This town is quiet; this town lies down like a sleeping dog; this town is deadsville. Not even a ghost moves. Not a dog whines. But Wildcat is on the hunt. We make some noise getting into the store. Real dark inside. Flash a torch around. Fuck, the beam hits a window. No worries, this town is a cemetery and the dead don’t walk. It’s then, I select me a nifty rifle. Always wanted to own one, and now I got one. Bullets too. But just for show, you dig, I don’t think of shooting anyone. Killing people is only legal in the army, buddy, and in the movies. Gangster movies I like. James Cagney, Little Caesar, tough and mean, but cool. Poor bloody Indians though in those Westerns. Never saw them win, not even once. Thousands of battles of Pinjarras, and all in glorious technicolour. That’s how it is for us’uns, that’s how it is. Try to make a stand and they shoot you dead.

Still, like Little Caesar I load that gun, then get the loot, enough to get us east. Outa that store and back in to the yard. Discovery. Yup, just like Australia’s been discovered. Someone alive after all in this graveyard. The dead walk. Duck down behind a pile of drums just as this powerful beam of light hits me in the face. Bang; off and running. That’s how I shot the cop. Big deal huh? Not much motivation there. Accident or what, I receive the big payback later for it. In bruises and this broken arm. Puts me in hospital, thank God, away from their grateful hands and boots. And now I’m waiting to be sentenced, locked in a cell with the old digger who’s just pulling outa the Dardanelles and into this cell along with me. Well, it’s going to happen any minute and I’m feeling kid scared, Anzac scarred because I’m only nineteen and I’ve shot an enemy ...

You know, in a past time, they take me away from my mum and put me in Cluny. I cry for three whole days and get over it, eventually. You know, there is the first time, they slam me in the slammer. I sorta shrink inside, but I get over it. You know, there is the time I get released, and as the gates swing open to let me through, I sorta feel my skin hardening all over. These are hard acts to follow, but I follow them up by shooting a cop, and now I’ve got all those nasty feelings in my guts again as I stand in that high dock staring over the courtroom. Why, I’m almost on the level of the judge. He glances at me with eyes that don’t see me. I'm nothing to him, man, just some dirt to be swept away. Well, I don’t wear a silly red gown and a stupid grey wig. Who does he think he is—the fairy godfather? He glances my way again and I can’t help smirking at him. And he gets a mean look in his eye; but now I know that I’m something to him, just as Jacko Turk became something to that old digger, Clarrie, who’s just got six months. Lucky old fart!

I look down into the body of the court where funny wigs are bent over papers, and really, man, I don’t wanta be at this fancy-dress party. I want out! But I won’t get out. Their words flow over me; the judge stares at me as if I’m an enemy of the state, and declares that I’m a menace to society and that society must be protected from the likes of me. He goes on and on. I think back to the battle of Pinjarra and wonder if any judge said anything about that day when they murdered our men, women and kids in cold blood and my great-grandfather just a kid of nine, the same age as I am when I’m taken from my mum, sees his mum die. Guess we were all enemies of the state then too and have to be taken care of for the good of their society.

Well, I don’t wanta be here and I wish he’ll get the whole thing over. At last he stops with the patter and gives me a long, long look. I know he’s going to get even for that smirk. I listen as he sentences me to ten years at the Governor’s Pleasure, and it’s then that the scream begins again in my mind. If I was holding that rifle now. If I am holding it now, maybe I’ll turn it on myself, cut off that scream for ever. That’s how I’m feeling, you dig?

The cop guides my body back down into the cell. The black van waits to take me and the muttering old digger, Clarrie, to Freeo. I don’t know how to react. There’s this screaming going on and on in my head, going on and on in my head blotching out all thought. I don’t know what to do, man, don’t know what to do, would you?

Wildcat’s eyes sparkle as he listens to Crow. Crow opens his beak and gives gleeful squawks which bode no good for the wild cat. He brings out his claws and lifts a pa w. ‘Now you don’t take on so,’ Crow caws, giving a little jump backwards. ‘No worries, you want to fly? Well, I’m telling you, giving you the proper info. Now, listen here. Dead secret this. Tonight the moon’ll be full. Well, you put your eyes on that moon. Fasten them there and keep on looking and looking. Maybe, better that you climb a high tree. Less distractions up there, and closer to the moon too. Just look at him, keep on looking and you’ll lift off, fly higher and higher towards that old moon.’

Wildcat nods trying to be wily. Crow gives that squawk again. He hops around the wild cat, seeming awful gleeful. ‘And what you want in return?’ Wildcat asks. ‘You know, scratch my back and I scratch yours’—and he extends his claws and Crow’s glee leaves him. He gets into a kind of panic, and his wings open and he flutters out of reach just above Wildcat on a low branch. Wildcat bears his fangs. Opens his mouth in a great big yawn, giving Crow a glimpse of his rippers and tearers. ‘You’re a tricky one,’ he says. ‘So just look at what you’re up against.’ So Wildcat snarls; but all the time in his mind is the image of Crow just lifting off the ground as if the sky belongs to him. He wants to do that, wants to fly far and free.

‘Man, would I jive you?’ Crow says in his hipster talk. ‘Man, you would,’ Wildcat says, very much the bodgie, very much the cool cat in his dark threads.

‘Not this time,’ Crow answers him, slow and easy to put him off the track. ‘You eat and leave me a feed, that’s all I ask. We work together after this. You flying will be able to catch anything on legs or wings. Just give me my share, that’s all I ask.’

And Wildcat relaxes and begins to believe Crow. It won’t hurt to try, and if Crow is lying, well, there won’t be a crow to crow around much longer.

That night, the moon leaps up into the sky. Wildcat wary at first gazes at it from the ground. It begins to call him, singing a sweet sky song to him.

Arrh arrh, munya mayeamah yah-arah,

Fly up and touch my skin.

And Wildcat begins climbing this big old gum tree. His claws grip and he pushes himself up higher and higher, right to the very top, where he clings with his back paws and feels himself swaying, swaying, swaying and the moon calling, calling, calling to him. He leaps off and up, one foot, two foot, and begins falling, falling, falling, screaming, screaming, screaming ...

‘And we come to this cliff, cobber, about as high as a prison wall. There’s a kind of a path up it and up we go with blokes dropping all around. All mates, not bloody pack rats, and we come out onto a flat bit of dirt, Pluggie’s Plateau as big as an exercise yard, but it’s as if the guards are lined up shooting down at you. A cobber, Tom, he gets two bullets in the left leg, another through his hat, another one through his sleeve and a last one that hits his ammunition pouch. I’m lucky, a bullet glances off his entrenching tool and gets me in the arm. There’s the scar, mate, see it. Bloody shambles it was, bloody shambles, just like going through the gates of hell, cobber. Just like that. Blokes falling down everywhere, wounded screaming everywhere: the gates of hell.’

And I come outa my funk, come outa that screaming dive into the sound of that old digger’s voice and through the barred windows of that van, I catch a glimpse of the outside walls of the prison. The van halts. I should’ve been looking out and storing up the memories of streets and cars. Instead I was inside myself and that scream. I’ve missed everything that should’ve mattered to me, and now the van has stopped outside the gates. They swing open and we enter through into my home for umpteen years ...

Well, what else was I expecting. A holiday on Rottnest? Though that isn’t a good place for Nyoongahs. One big prison. Devil’s Island. Creepy place. The spirits of the oldies are roaming around there still trying to escape. Well, it’s what I’ve heard. Don’t make up things like that, or even believe them for that matter. Still, I ain’t been to Rottnest. Been to Freeo though. In there now, and perhaps worse things have happened here. Freeo, that’s a pun. I read all these books and that encyclopedia and like to air my knowledge. Ain’t got anything else to do with it, have I, you dig?

Well, back to the van, and the gates open and the engine starts and we lurch forwards to where they ain’t going to welcome me with open arms. A week or so out and back for longer than I can bleeding imagine. I don’t know, I don’t know. I can’t do it on my head. I’ll flip out if I think about it.

They open the back door of the van and the old digger Clarrie is the first one out. His old serge major is waiting for him, and he, that’s Clarrie, comes to attention and gives him a big salute. ‘Come off it, you silly old sod,’ the screw shouts. ‘Your brains scrambled, or something. This ain’t no bloody army camp. It’s worse than that.’

All the same, the screw has put a grin on his big red mug; but he scowls when I get out. ‘Well, well, who do we have here,’ he shouts; but I notice he keeps his distance. It’s then I start to realise that perhaps going after a copper means something here. It means you could go after one of them too, and something else. Coppers and screws hate each other. That means I won’t be getting bashed up for doing one of them.

I line up with Clarrie and we are marched into reception. Well, I’m used to it. Ain’t nothing new to this wild cat. It’s the same old eye-fucking thing with the stripping off of everything that makes us what we are. Poor old Clarrie, the flasher is able to flash all he wants to. Feel a bit sorry for him. No one here wants to look at his old limp prick. All the same, I sneer, ‘Flash it Clarrie!’ Then ease off as he looks at me as if all his humanity has been lost. Well, what was his flashing but a sign of his humanity. He lost something at Gallipoli, and so became a rummy and flashed what he thought was his manhood at the world. Silly old cunt, okay; but does that make me a silly young fuck? Naw, never!

Still, he makes his stand just as I make my stand. Now that stand is taken away from us. We are naked bodies to be arse examined by a doctor, to be deloused and showered. We are nobodies. Next will come the cutting off of my hair. I was allowed to grow it somewhat before I got released. If I had’ve stayed out, it might have reached a decent length. No decency in here. Well, fuck them. And nakedness is no degradation. We stood naked forever before they came with their clothes. Nothing wrong with my naked bod either, man. Put a little swagger in my walk; but keep that scowl on my face. They circle around me warily. I’m getting the star treatment. Copper shooter, eh!

That nakedness doesn’t last long and soon I’m in prison grey and the last of the outside disappears as my hair is trimmed back to my scalp. Now, I’m a convict. A prisoner of the state, numbered and dehumanised. Fuck it; fuck it, fuck it! To hell and back. I can’t stand it. I keep collapsing into myself. Have to find something in my mind to pull me through. I’ll get used to it. I will, I will!

I stand at the door of the nightclub looking real cool. My hair’s slicked back just right and the curl dangles over the forehead just right. Everything’s just right and I have a roll of bills in my pocket and I’m ready to groove the night away. Black pleated pegged pants; black shirt; narrow white tie to go with my long draped sports coat. Got my brothel creepers on too and I’m ready to creep. I put a little swagger in my walk as I brush past the bouncer. Him, he can’t bounce. Can do him with one hand tied behind my back and he knows it, but I’m cool, you dig?

‘How’s it with you, Fred?’ I make with the chatter as I stop a little away from him so that he can take all of me in. I pull one of the new long fags outa the pack and light up. I don’t offer him one. He isn’t one of us, is he?

He eyes me as if he would like to tread on me then lifts his foot cautiously and replies: ‘A little quiet, but we got a new singer and she’s got a voice and a bod along with it.’

‘Bet you, she’s not for you,’ I smile as I peel off one of the bills and let it drift into his hand like a snowflake. Inside my eyes sweep over the room. I ain’t one to keep in the shadows. Brown, looking good and on the prowl. I make my own space as I drift on by in my crepe-soled shoes. I sink into a chair at the front of the place. Right in front of me is the breasts of the singer moving just for me as she sings:

‘My man wears pegged pants,

Long draped coat and a narrow tie,

Boy, when he gets moving,

He makes me puff and sigh.’

Her lips move around the words and push them out at me. She starts on another verse of the song:

‘My man, he’s built so big and fine,

Yeah, I tell you, he stands tall,

Got, his mumma working overtime,

Every night we have a ball.’

The waiter comes with a drink on the house. I sip and watch her fine breasts moving under the green silk of her fine dress. They’re moving just for me. Man, I know it’s going to be my night ... I’m walking down that street in that posh suburb, and this kid, this girl-child with mother of course comes outa this nice neat house, all bright and clean, with a nice green closely cropped lawn around its face. Nothing outa place here excepting me. And then this kid, this girl child picks up a pebble, and lets fly with all the viciousness which lurks in the human breast. It hits me on the right shinbone. I look down at the instant scar, still hurting like mad, man. I look across at that little bitch with hate in my eyes and snarl: ‘You rotten little moll, just wait till I get ahold of you.’

I hurt! I drag my leg as I move towards her, and the white lady, the mother gets all upset and protests: ‘She’s just a child.’ I reply, ‘So am I lady and I’m going to get that little cunt’—and just then my leg collapses under me and I’m down on hands and knees, down on all fours, just a wild cat and timidly I belly level away, as that fucking little bitch picks up more pebbles and the white lady smiles and says: ‘You aren’t no child. You’re just an animal and the RSPCA should come and put you down ...’

I come outa my daydream and mutter, ‘Well, lady, satisfied, now I’ve been put down?’

And the screw escorting us across to the cell block, snarls: ‘Keep your trap shut.’ And I shut it, for I can’t daydream myself outa this one. All I do in my head is scream and scream. This is going to be my home for the next umpteen years, Christ!