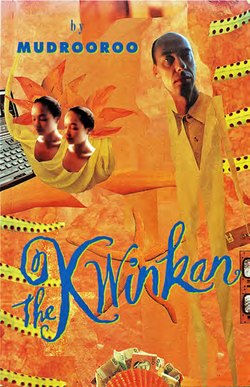

Читать книгу The Kwinkan - Mudrooroo - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SESSION ONE

Оглавление‘Yes, well I did know, or should that be, I do know Detective Inspector Watson Holmes Jackamara, and I have read, or let us say glanced through the volume of his exploits, or perhaps I should say cases. And you are the, the chronicler of his life? I find it very interesting, most interesting; but what has it got to do with me? You see, as I did know the Inspector I was ready to peruse the book and did, but, to be precise, I thought that you fictionalised the cases too much, not as to the sensational aspects, but as to appearing to get into the minds of the participants in the tragedies. I see by your raised eyebrows that you are querying my use of the word “tragedy”? Well, sir, I do prefer the formality, I have no wish to extend this brief meeting into friendship, I regard all police cases as tragedies, the result of individual strivings and aspirations colliding with the social mores which may be seen as fate. Social collapse averted by individual collapse and so it goes on. I find little of this in your fictionalised working over of the participants. Well, it is only what must be expected, for after all, and for that matter how could you really begin to delve into and understand the inner workings of not fictional characters, but real people engaged in the tragedy of life often to such a degree that they put their all on the line. Perhaps only the policeman, the avenging fury, might begin to understand and love aspects of the criminal; but not all, sir, no, not all for after all he is no psychoanalyst; but then what has psychology got to do with the understanding of a human nature enmeshed in tragedy? Ah, so you interview people? Interesting, and the details of the cases? ... from the Inspector himself . I remember, even now, that he was an excellent raconteur. In fact, I feel that I am ready to cooperate in your, well, in your project of literary realisation.

‘I remember Jackamara, I’m sorry, Detective Inspector Watson Holmes Jackamara. It was like this. At that time, I was standing for election to the federal Parliament and he was detailed not only to be my minder, but to pull the black vote onto my side. You see, well, I can admit it now, I was very much the city slicker. Still am for that matter, but, well, you may ask, what has this got to do with my connection with the Detective Inspector? What, you say that he is now a Doctor of Criminology! Well, well! It appears in this world only I remain constant and on the down turn ... Well, when I met the good Doctor, the black vote was substantial, very substantial in that electorate. It was decided by those in power that I go around to the various settlements and missions to present a sympathetic ear to their grievances. Naturally, I was to promise nothing; but in those days in Queensland the mere presence of a parliamentary candidate amongst the blacks was like the visit of royalty. Still, I needed an “in” and so the Inspector was provided for that “in”. We got on splendidly, well, we did to a certain extent, as much as it was possible for a white and black man to get on. He was a great one for the stories, and as our enforced companionship wore away his reserve, he gave me much enjoyment on the road to some of those missions which are so remote that to say out of sight is out of mind is quite correct. Why, he even took me to his old mission home.

‘By that time, I was used to these clusters of abandoned humanity lurking on the very brink of my vision. To enter into one of these clusters was a trial. The blacks were stand-offish, preferring to gaze away rather than towards, and the white persons in charge were little better. They on the whole were suspicious of politicians. Some, I saw, had identified almost wholly with their charges; others lorded it over them, and the rest, the majority, suffered their isolation and were ready to fling their petty grievances towards me. Naturally, I ducked them.

‘Jackamara’s home was typical of these abandoned missions. The better ones had been ordered by the State Government to become municipalities; others like his, a few dilapidated houses squared about a church and a rambling bungalow, the once home of the missionary, were placed under the control of a government agent and forgotten. When I arrived, I found that the agent had taken leave of absence. His headquarters, the bungalow, lay silent behind a mesh fence topped by barbed wire. A light-skinned lad pulled forlornly at the hasp of a heavy padlock securing the gate.

‘We alighted from our vehicle in the dusty square. Not a soul in sight except that kid pulling on the lock. Then, then there erupted from between two houses a group of men beating the ground with sticks and yelling, “Snake, snake!” I stared at them nervously, then with a slight grin of derision as I saw the serpent they were after slithering towards us. I could recognise a harmless grass snake when I saw one. I stood there as they approached. Then one of them quickly stooped, grabbed the snake by its tail and flung it at me. I caught what I considered a harmless serpent and held it up. They came forward warily. I looked down at my catch, then gave a start. My God, it was a deadly brown snake. I flung it from me with a gasp of horror. The men watched it disappear under a house—then turned to us.

‘Jackamara was amongst his mob and went from man to man explaining my mission. It seemed that handling the snake had been a test of some sort and one which I had passed. We, or rather I, was allowed to camp on the porch of the deserted church for the night. Jackamara got the camp set up while I sat on the camp chair. Individual men approached to sound me out. I hummed and hawed in my usual fashion as I blathered my way through the usual requests; I stated strongly that I was in the running for Minister of Aboriginal Affairs, and agreed to carefully consider each and every problem when I was elected and entered the Ministry. I even made a show of taking notes.

‘Finally, and as the sun disappeared beneath the dust and the darkness flickered with the flames of our fire, I left my chair and sat on the porch steps to watch Jackamara preparing supper. A huge billy of tea hung above the flames. By the time it was bubbling, men had appeared from the darkness and settled about the fire. Soft voices murmured and tired with, with keeping up the pretence of wishing to help these people who were as alien to me as I was, I am sure, to them, I fell into a doze ... I came out of it and into a story being narrated by Jackamara.

‘A remarkable story, quite remarkable. It stays in my mind, stays in my mind as much as she stays there. No, she has little to do with this, has little bearing ... Is that tape-recorder running? Remarkable things, tape-recorders. You could say that they tap the stream of consciousness; but, sir, remember, keep it clearly in mind that I retain the right to vet all material and, and nothing must allude to my identity. Remember the laws of libel. You see I still have enemies. Yes, even now when I am at a low level in my, in my career, and that is why I ... Well, why should I record my, my downfall, when you are only interested in that black policeman? ... But, remember, once, then, I could have become the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and have had him at my beck and call. Alas, it was never to be.

‘Jacky, as I called him, was still a simple detective then. Perhaps not so simple as you depict in your case histories; but in those days few appeared ready to acknowledge his uniqueness. It is still hard for me to believe that you have not made up most of those so-called cases, though, no, in hindsight ... Well, now he has a reputation second to none in the history of the Queensland Police Force. He well deserves that honorary doctorate, and perhaps in one of your future volumes you will detail what must have been a very impressive ceremony ... Sorry, sorry, I know that I digress. I am forever digressing. My life is one long digression; but, sir, over the years things have not gone right with me. The story? Yes, the story. It seems but last night. There sits Jacky at the fireside. How mysteriously his dark face and the dark faces of his mob glow in the flickering flames as he begins to relate an anecdote which I then took as rank superstition.

‘He declared that it had happened when he was a young kid and that his Uncle Willy could vouch for every word. He looked across the fire at a stolid bloke whose eyes reflected red and mysterious from the flames. This man, I knew must be Uncle Willy, and he nodded his shaggy head in verification. As Jackamara flicked his glance towards me, I too found myself nodding, then he went on addressing his words to me, his gaze flickering at times to Uncle Willy at salient points ... And the story? Well, it is as good a beginning as any for this tape. It seems that once as Uncle Willy and his maternal grandfather, I forget his name if I ever knew it, were walking through the bush in the early evening, a min min light came floating towards them. The old man ignored it and kept on walking, but the uncle, he slowed down a bit. He hung back as the old man strode on. In fact, Uncle Willy, it seems, was not one to put his best foot forward and hung back so far that he was at a safe distance when the light flared into a beautiful woman with long flowing hair. He watched from a distance as she spoke to the old man. He saw him go off with her towards a low hill which was a pile of boulders and rock slabs. “It’s what you fellows call The Devil’s Marbles,” Jackamara informed me, and I recalled that he had pointed the hill out to me when we passed it on the way in.

‘Uncle Willy didn’t have to be told that it was what the local Aborigines call a Gyinggi woman, I see you nod at this, and that she had sung, you know what that is, the old man and forced him to follow her to her home in the rocks. In fact, the hill, which the Inspector offered to stop at on the morrow, had a bad reputation and was taboo to the local blacks. They said it was the haunt of spirits, of spirits called Kwinkan. Except they are not spirits, for that Gyinggi woman when she enchanted men drained the very flesh from their bones until they became stick-like beings. Uncle Willy didn’t want this to happen to the old man, so he rushed off back to the mission for help. Half-a-dozen men reluctantly came back with him, urged on by an old bloke who believed that he had the necessary, I suppose you might call it, medicine to force a passage through to the Gyinggi woman and her prey. By the time they reached the foot of the hill, it was almost pitch black. They saw a light glowing half way up the slope and carefully they climbed to it. Hard work it was, for it was no joke making your way across those piled-up rocks in the dark. Finally, they reached a huge tree emerging from the slabs of rock. It had pushed aside the slabs and the light came from underneath one of the tilted slabs. The old fellow mumbled a chant of some sort and came creeping towards the light waving a bunch of feathers, which, it seemed, dislodged any spirit which might be lurking in the branches of the tree ready to spring down on them. They reached that slab and peered beneath. The old man lay there stretched out seemingly asleep. No one else was in the place, then the strange glow began fading. They dragged the old man out. They shook him to bring him to his senses. He came to snarling and snapping like some wild animal. They had to hold him down. One of them who worked for the medical clinic at the mission, thrust a stick between his teeth and then tied his hands and feet. Well, they carried him back to the mission and kept him locked up in a room. Then one time they go to that room, and you know what? Well, that old grandfather had dug his way out through the floor. A concrete floor mind you. It was the last they saw of him. He had returned to that Gyinggi woman and was lost to the men. That was the end of him as a man. Well, at least this is what Jacky told me that night. He went on further and said that such a man taken or lured by those women is sucked dry. He becomes a Kwinkan, thin and elongated, living in the rocks and crevasses, afraid to face the light of day and other men. He loses his nerve, just as I’ve lost my nerve. It can happen to the best and worst of us, mate, the best and worst of us. You better believe it!

‘Well, stories are stories and Jacky had a fund of them, and most of them just as meaningless, that’s what I thought then, smiling before wondering why he had directed that particular story at me, a soon-to-be-elected member of Parliament, a minister too, and thus on his last visit to this godforsaken mission, for let me assure you that it was that. It was a place made for superstition and I remember clearly that I darted a glance at the stern face of the detective while I asked within: “How come an officer of the Queensland Police Force could believe such rubbish?” ... but then the answer was real easy; he was an Abo, no offence meant, and that settled the matter for me.

‘Well, the tape-recorder is still running and, I’ve made a start. Why there? No matter, I’ll just keep on. You’ll have to listen if you want to hear about the time, or the times that Jacky, well to give him his due, Detective Inspector Dr Watson Holmes Jackamara figured in my life. You’re the one who gets inside the minds of real people, so you have to listen and get inside mine. Now, don’t worry, don’t worry, Jackamara is the hero of this tape, and I’ll get to him, but well, well, what about my life? You have to pass through some of it to get to him, so you better, better listen, take me along with the good Doctor and then cut and shape it; but, but, I have a veto on the material, on my life as it were. It is my life, I want to keep it mine ...

‘Life, you seem to question. Well, we all develop some sort of philosophy of life. That is if we live long enough. Life, I thought once it was what might be called, other-directed, a force rushing into the future loaded with all things nice for me and you, but especially for me. Well, that was then. The old experience eventually gangs up on you and you get some degree of reality, the reality factor going for you. Well, first of all, if you ask me what is life, I must answer, but from what position do you expect me to answer? As the head of a computer section, a minor bureaucrat to be precise, I might answer that it does not compute; or if you wish I shall refer the matter to my division head. So you see I cannot answer it from my official position; but as a man, a human being talking from experience I may. Oh fuck it, what was the question? What is Life? What is it after all but just bits and pieces of memory caked with some sort of emotional slime? Some are tedious, some exciting, and some, I must admit are even terrifying. Well your friend, Jackamara, played a part in my life and thus created some pieces of my memory. It is these which you expect me to open like a computer file and reveal to you the contents in all their pristine accuracy. Well, mate, it doesn’t work like that. I’m not a computer and I expect some, well, let me call it remunerative cash—no cheques please—for my ability to open these files to you.

‘What, you say that they have an importance only to you? Well, they are mine by the law of privacy. Intellectual property! I own them, mate. Admit that they are important to me through right of ownership ... but what about others? The laws of libel protect them. I am not a monad existing only in and for and by myself. So my memories are important not only to you in your function as an eventual narrator, but to me and others as well. I am the archive of such memories; and because they are an archive they have an importance towards forming the public view of contemporary history. You see, mate, then I was standing for a seat in Parliament and on the verge of becoming a minister and more important than that friend of yours. Yes, more important, and so if you want to learn about him, you’ll have to pay as you go and learn about me as well ... And don’t smirk, don’t even wonder why I am so thin now. So much, so much a Kwinkan, a thin stick of a body attached to a thick, misshapen penis. Well, she did for me, mate. It happens to the best and the worst of us, and so it happened to me and it all started from that story of Jacky’s. I don’t know about you people, you Abos, there’s something not quite right about you mob, something different. Underneath the old suit and tie of assimilation there beats the heart of an Abo, but no offence, mate, no offence. Just one of those things which are part of the reality factor, then I am pissed off about everything. There’s been little contentment in my life over the last years. But, no worries, eh? Or as my esteemed leader used to say, “Don’t you worry about that”; but I do, I do. Might have some kind of health and some kind of job, but everything’s not apples, mate. Still, it wasn’t always like that, like this. No, it wasn’t. No, not at all, and one of these days, when I get myself together, things’ll change, will change, you'll see; you’ll all see. I’ll be on top again!

‘Well, the tape’s running and I have to start somewhere. No, I have started, got to continue. Well, it was over a decade ago, at the end of one of those boom periods for which the economy of Australia is noted, I found myself at the end of my tether, or almost, for the recession had condemned me to seek out some quick, profitable venture to stave off not bankruptcy, this is in the strictest confidence—I really will have to vet this tape—but imprisonment. It was then after a too hasty deliberation that I decided to cash in my last favour with the heir to the then Premier of Queensland, a man, who did not like being reminded of old obligations. He made a quick phone call and shifted me as problem over to the head of his party. He greeted me with a cold smile which in rosier times might have warned me to keep on guard; but times were tough and so I listened to his plan to present me as a candidate in the forthcoming federal elections in an electorate in which I knew no one and no one knew me.

‘He assured me that the seat was as safe as houses and that my election was in the bag. Some of the old guard had been caught with their hands in the till and thus new blood was needed. I was supposed to be a pint of that new blood; but, from the very beginnings, ugly rumours hissed through the corridors of power that I was an upstart who, apart from party donations, had little political clout and no savvy. These rumours came to my ears, but the political bosses laughed them away. It happened to all new chums, they declared, and added it was a way the wheat was sifted from the chaff. I accepted their reassurances, as I was certain that I did know politicians and how they conducted themselves in government and towards industry. In fact, I felt that I was just as good or as bad as the best or worst of them and could further my interests with much more discretion. So much for my naivety.

‘Next came a solemn interview I had with the horrible Prime Minister of our country who had seized power by ruthlessly splitting a coalition of the conservative forces and by establishing an alliance of convenience with a party masquerading as the friends of the poor and the afflicted. There were no problems here for me. The PM was an old school chum who believed that the public school tie knotted around his withered neck gave him the right to plunder at will. I hoped that he did not remember that, well, I was one of an unselect group who had gained entry into the school through scholarship. He didn’t let on. My powerful, rich, old school chum greeted me with an outstretched hand and a warm smile to balance out the ice in his wary eyes. “You see,” he exclaimed, “we never forget our friends.” He let my hand drop. “You shall be an asset to the party, ministerial material. New blood is needed, new blood,” he exclaimed ...

‘ “I still have to get myself elected,” I replied peevishly, thinking that my business mates were paragons of honesty compared to this lot. Still, this old school chum owed me a favour. On many occasions I had helped him with assignments, though I doubted that this was something he might wish to remember.

‘ “Never you mind; never you mind,” he babbled in the nebulous fashion which was the political gift of Queensland to the rest of Australia. “A formality, a formality,” he burbled, flashing me his false teeth and even rubbing his hands together. I stared at him as he chattered on. “No worries, no worries, a safe seat and you’ll have every chance of taking it with an increased majority. You are what we have been looking for. Intelligent, charming and, and pleasant. Why, with your rugged looks, you’ll capture the ladies. You’re lean and hard and these’ll add to your appeal in the bush. You’ll see ... You’re in already ... but you must understand the situation, understand what you may and must not say. Simple, I assure you. First past the post too.”

‘His assurances and the classic buttering-up job failed to ease my doubts. I thought my leanness perhaps bulged with malnutrition. I attempted a warm smile of complicity which fell away as I recalled that a cartoonist on the Courier had already caricatured me as one of the five horsemen of the apocalypse of recession. It did not help matters when I recalled that our beloved Prime Minister had been placed in the lead. Grimly, I listened to his advice ...

‘ “And above all, no politics! No politics! Leave ’em to the Opposition. They always try to drag in politics and come a cropper. And above all don’t get involved; don’t get carried away by the side issues. Remember, it is a rural electorate, and the voters are only interested in one issue, and one only: the farm subsidy! Wool prices, wheat sales, land rights, the kangaroo menace—ignore them. The farm subsidy is not only to be continued, but increased—adjusted against the rate of inflation. That’s all you need to know. Let your opponents wallow in the swamps of generality, stick to the farm subsidy. Do you know anything about the farm subsidy?”

‘ “My God,” I exclaimed, “I’ve always been involved in urban property. Why, I’ve never heard of it before. Should I bone up on it?” I queried.

‘ “No, no,” the PM said hastily. “That won’t be necessary. We’ll get a few set speeches for you and some questions and answers to read through. These’ll be enough. Just stick to ’em and you can’t go wrong. And above all-don’t improvise! Don’t get carried away with personalities or general views. Remember commit yourself to nothing, except of course, the farm subsidy. Commitment is dangerous and a threat to the integrity of the party. You know, between ourselves, don’t take it personally, old chap, I’m not reproaching you, but there have been rumours, but ...” and he smiled knowingly.

‘My face had long gone numb in the mist of his waffling. The PM was renowned for concealing his ineptitude behind a fog of generalities, a trait he had inherited from his predecessor; and he had successfully done it again. Now I eased my facial muscles into what I hoped was a smile of, of, well, of complicity. After all we were in the same boat and had to pull in the same direction. This I thought was certain, though as I stared into the face of my old school chum, I had to keep a snarl from my voice. I met innuendo with innuendo.

‘ “Perhaps, there are other and more pertinent rumours circulating,” I stated, as if I was privy to such rumours, though as a new chum, I was denied the corridors of power; but then I had other contacts. “It seems,” I stated, “there is the matter of a lack of timing. If the Government hadn’t acquiesced in that steep rise in interest ...”

‘He interrupted me with a dry laugh, almost a cough, and said with an air of superior detachment: “We are talking about different things, old chap. You see, I’m covered by my position. Any accusation is a political attack, and as for the interest hike, that is not your concern.” Thus, having put me in my place, he swung back to the forthcoming campaign. “You only have to remember the farm subsidy and the adjustment against the rate of inflation which naturally has calculated in it any interest rises. Push that down their ear holes. Don’t deviate one iota from it and you’ll get the white vote, and as for the black vote ...”

‘That was where your detective came in, of course. Then, after arranging for funds to be forwarded to me, he pressed my hand, offered me the certain luck of the draw, then showed me the door.

‘I faithfully followed his advice before I discovered that it was completely worthless. My opponent not only crushed me with a huge majority, but at one time I was in danger of losing my deposit. I attributed this defeat not only to the disastrous economic climate and the saddling of me with an Aboriginal bodyguard which drew prejudice towards me (I was seen as soft on the Abos and therefore against the rural interests), but also to the abysmal scheming of the PM and his failure to come to my rescue when the campaign took on a personal tone and I was reeling under attack from all sides.

‘I became a witness to how a victim is set up in this great country of ours. Only Jackamara stood by me. He said that the local blacks were 100 per cent behind me, but demanded a statement on land rights. Not bloody likely! I hummed and hawed and lost even that base. My opponent, a wealthy landowner who had dismissed his black employees when he had to pay them a decent wage, pointed the finger of scorn at me. He became the hero of the piece as he laughingly contrasted conditions on a clapped-out station which had been passed over to the blacks with the thriving nature of his own properties.

‘ “Yes,” he declared, “I admit I have made a somewhat comfortable living from my land ... but this has come through hard work,” he shouted out at the church fetes and sheep sales. “And what I have done, they could do,” he yelled in a great shout which echoed in the greedy hearts of all those farmers struggling as much as the blacks were struggling to make a success of their farms.

‘Evading the issue, I flung what I considered the reality of the farm subsidy, cents against dollars, which he adroitly turned against me as a hidden means of keeping off the market the property on which the blacks were trying to scrape out a living. He ignored the farm subsidy and concentrated on the sudden rise in beef prices. His posters fashioned like hundreddollar notes flashed his complaisant face as they screamed: “MONEY COMES FROM LAND WELL WORKED AND MANAGED.”

‘If only they had stopped and thought, but in the town pubs, his agents shouted drinks all round while they trumpeted: “Well, he knows what he’s talking about.” Drunken heads would nod into their drinks and soon this man, seen as one of them, was acclaimed with a frenzy which increased by the hour. Who needed a subsidy when beef prices remained steady at the new high? Market forces were triumphant!

‘My opponent achieved wellnigh divine status when the Brisbane newspapers exposed certain dealings. Now it was country against city, and his victory was assured. My own past, though not my identification with the city, remained all but buried. I found myself at the head of a small minority on the side of accountability in politics. One evening, towards the end of the campaign, I went into the pub in a small town with Jackamara by my side. It was the usual crowd, good-natured in grog, and they even allowed me time to say a few words from the band platform. As I knew the town was dirt poor, I began speaking on the farm subsidy and how it rose in relation to the official inflation figures. This, I declared, would help the weaker rural sectors in which I unfortunately included the Aborigines.

‘ “Fuck ’em, they get too much already,” someone shouted.

‘ “This is untrue,” I unwisely shouted back. “I have seen how these people live, and by my side is one who can tell you about the third-world conditions.”

‘This was too much for the men to take. I had unwisely settled on a taboo topic. A glass whizzed by my ear and splattered on the wall behind me. Others followed and I hit the deck. I huddled there fearful as a hail of missiles flashed over me and beer splashed down. Desperately I called for Jackamara, and then other missiles came from the reverse direction. There was a shout of “Get the buggers” and the bar became filled with large black bodies and fists. Jackamara had enlisted the blacks from the segregated black bar to come to my rescue. A running battle ensured huge headlines detailing a “Race Riot”. With a bruised face as dark as those of my allies, I saw myself going down to defeat. It was then that I knew that I had been set up: I would never become the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs!

‘This became clearer in the final hours of the campaign. My election committee, which at the beginning had been very accommodating, now refused to meet and consider my complaints, or even to plan an alternative strategy. I pressed them to honour their pledges, only to find that there was a serious shortage of funds and rumours that certain moneys had been diverted to buy the black vote. It was then I tried to get in touch with the PM. He was unavailable. At the beginning of my campaign, he had promised to make a whirlwind tour of my electorate, but since then not a single word from him. In desperation, I threatened to go to the media and even tried to plant a few stories which might embarrass, but not harm the election prospects of the party. In return certain newspapers attacked me. It was said that I had sent a truckload of grog to an Aboriginal settlement. Under cover of glib journalese, daggers of wounding allusion slashed out. To the party, I was a lame duck. Real or imaginary polls now revealed that my party would be returned to power; but each and every poll showed that my seemingly safe seat was not only in doubt, but lost owing to my ineptitude. I sat fuming as I crashed to defeat. My only apparent friend at the time was my minder, Detective Inspector Watson Holmes Jackamara, but even he had proved a liability. He, after all, was a blackfellow.

‘Well, now I have detailed the first period of acquaintance with that policeman. I doubt that he was privy to the plot; but the sight of him beside me on each and every occasion was an element in my downfall. I must admit I breathed a sigh of relief when his job was over and he returned to Brisbane. It was then, that determined to bare all, I rushed to Brisbane where the PM was holding a victory rally. To my consternation, I received an appointment without delay.

‘ “My dear, dear chap,” he exclaimed, coming to me with his hand outstretched. I should have ignored the touch of that Judas, but beggars can’t be choosers, and after all he was the PM. “My dear, dear chap,” he repeated, pumping my hand once, then letting it fall like one of my how-to-vote cards. “I’m so sorry, so very sorry, but you would drag in extraneous issues, such as land rights. What on earth made you come down so heavily on the side of the Aborigines! Why, it threatens our whole policy on that question. Upon my word, I thought that you had more sense. Still, I never would have believed it. There was a swing against us all over the country and but for another reversal of coalitions we would be sitting on the Opposition benches. Well, well, I never would have believed it,” he said shaking his head. It rankled that my opponent was now a member of his cabinet.

‘ “Don’t give me any of that bullshit,” I interrupted him coarsely. “And whose bright idea was that to give me the only Aboriginal detective as a bodyguard?” I shouted, banging my fist down on his ornate desk and making the papers jump. “I was set up like a dummy, don’t deny it!”

‘ “Policy, policy,” he murmured. “After all, you had to have credibility with the substantial black vote.”

‘I shook in fury, clenching and unclenching my fists. In an attempt to pacify me, he offered me a chair, thank God, not a seat, then poured me a drink. I downed the glass in a single gulp before grinding out: “All you bastards are laughing at my expense. Well, we’ll see who has the last laugh. I’ll expose you for what you are. The whole country’ll know of it. We’ll see; we’ll see. In fact with this reversal of coalition tactic, there might be a case to be brought before the Electoral Commission. Once, yes; but twice?”

‘I broke off choking with rage and humiliation. The PM waited a moment, then said: “Please be quiet and listen to me. Please, please. I’ll let you in on what happened. We had no way of knowing, or of getting word to you. Strategy was planned and put into operation on a day-to-day basis. You’re new to the game and don't know how these things are settled ...”

‘My rage had fallen away and I let him continue. Quietly, he explained: “Your rival, he was proving too strong for us to contain. What could we do? It was by sheer chance that he went against you in the first place. All preliminary polls showed that the result would be close and that the deciding factor would be the black vote. So we used what we considered our trump card and brought in Detective Inspector Watson Holmes Jackamara. Well, we had never considered the amount of prejudice against Aborigines in the district. The farmers are frightened that their land may be alienated from them. So what could we do? Party comes first and your opponent was strong material, cabinet material, just what we needed. Everyone knows him. Very popular, indeed. Just a miscalculation. Sorry about that; but our country needs the strongest government in these somewhat difficult times. I am sure that you would have made a fine Minister of Aboriginal Affairs ...”

‘ “Christ,” I burst out. “Cut the twaddle, you aren’t in the house now. I don’t care what the country needs; I know what I need. I relied on you, and now thanks to you I’m finished. I’m overdrawn at the bank not by hundreds but by thousands, and at this very moment my creditors are about to pounce. They’ll skin me alive. I’ve barely got the price of a decent meal in my pocket and when my credit card is dishonoured, I’ll be dishonoured. Christ, can’t you see the fix I’m in?”

‘The PM was a good sort, perhaps. He draped an arm about my shoulders and said: “You had to get it off your chest and now let me say ... I’m prepared to offer compensation ...”

‘ “Reparation is more like it,” I ground out.

‘ “If you wish it to be so ...”

‘ “In full.”

‘ “Completely and utterly.”

‘He smiled and I scowled back in disbelief. “Government needs good men such as yourself,” he stated, as he escorted me to the door. There we shook hands to seal the bargain, whatever it was. I was to go to Canberra where many government departments still remained in those days ...

‘Well, that is that. Quite a bit about Jackamara too. A visit to, to his run-down mission home; an account of an Aboriginal story as from his own lips, and his extricating me from what might have been a nasty situation. You can see from this that my account is valuable and we must settle the worth of its value. There is more to come, and I feel that certain, certain facets of the man should be brought out. I did establish a relationship with your Detective Inspector Dr Watson Holmes Jackamara and this must be of worth to you.

‘Why, you ask? Cause, well, you know, then, it was, was, I had been set up and with him keeping tabs on me. And, and this set-up continued and your Detective Inspector Jackamara was there to witness my further humiliation. True indeed. And now he is a doctor and what am I but a lowly clerk. Where is the justice in that, I ask you, where? Now, switch off the tape-recorder. I insist. We must discuss the terms and conditions as well as the payment for further sessions. I refuse to continue, sir, without such sureties ...’