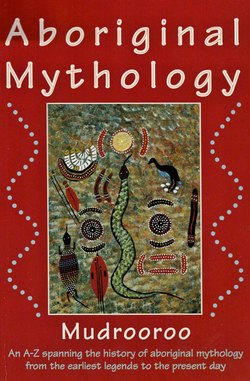

Читать книгу Aboriginal Mythology - Mudrooroo - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

B

ОглавлениеBull-roarers

Baamba Baamba (Stephen Albert) is a story-teller and singer from the Broome area. He has also acted in Bran Nue Dae, an Aboriginal musical which has played to packed houses throughout Australia.

Badurra See Ground carvings and sculptures.

Baiame See Biame.

Balayang Balayang bat mythology exists only in fragments and much has been lost. To the Kulin people of Victoria Balayang the bat was a brother to the great Bunjil the eaglehawk, but lived apart from him. Once, Bunjil asked him to come to where he was living, for it was a much better country, but Balayang replied that it was too dry and that Bunjil should come to where he was living. This upset Bunjil, so he sent his two helpers, Djurt-djurt the nankeen kestrel and Thara the quail hawk, to Balayang. They set fire to his country and Balayang and his children were scorched and turned black.

Because of his black colour, Balayang was associated with Crow and thus belonged to the moiety in opposition to Eaglehawk. This is in keeping with another story about Balayang which credits him with creating or finding women – and thus marriage partners – for the Eaglehawk moiety. One day Balayang was amusing himself with thumping the surface of the water and he thumped away until it thickened into mud. Something stirred and he took a bough and probed the mud. Presently he saw four hands, two heads, then two bodies. It was two women. He called one Kunnawarra, Black Swan, and the other Kururuk, Native Companion. He took them to Bunjil, who gave them as wives to the men he had created.

To the Kulin people, Antares symbolized Balayang.

See also Eaglehawk and Crow.

Balin the barramundi See Milky Way.

Balin-ga the porcupine See Great corroborees.

Balugaan See Dogs; Tooloom Falls.

Balur See Barrier Reef.

Banbai See Bundjalung nation.

Bandicoot ancestor The bandicoot ancestor myth is found among the Arrernte community. In the Dreamtime everywhere was darkness and the bandicoot ancestor, Karora, was lying in the earth asleep; then from him sprang a tall pole, called a tnatantja. Its bottom rested on his head and its top rose up into the sky. It was a living creature covered with a smooth skin.

Karora began thinking and from his armpits and navel burst forth bandicoots who dug themselves out from the earth just as the first sun spread light across the sky. Karora followed them. He seized two young bandicoots, cooked them and ate them. Satisfied, he laid down to sleep and while he slept from under his armpit emerged a bull-roarer. It took on human form and grew into a young man. Karora awoke and his son danced about his father. It was the very first ceremony. The son hunted for bandicoots and they cooked and ate them. Karora slept and whilst sleeping created two more sons. This went on for some time and he created many more sons. They ate up all the bandicoots which originally came forth from their father and became hungry. They hunted far and wide but could find no game. On the way back, they heard the sound of a bull-roarer. They searched for the man who might be swinging it. Suddenly something darted up from their feet and they called, ‘There goes a sandhill wallaby!’ They hurled their tjuringa sticks at it and broke its leg. The sandhill wallaby sang out that he was now lame and was a man like them, not a bandicoot. He then limped away.

The hunters continued on their way and saw their father approaching. He led them back to the waterhole. They sat on the edge of the pool and then from the east came a great flood of honey from the honeysuckle buds and engulfed them. The father remained at the soak, but his sons were swirled away to where sandhill wallaby man they had lamed waited for them. The spot became a great djang place and there the rocks which are the brothers are still grouped around a boulder which is said to be the body of the sandhill wallaby man.

At the sacred waterhole where Karora is said to be lying in eternal sleep, those who come to drink from it must carry green boughs which they lay down on the banks before easing their thirst. It is said that Karora is pleased with this and smiles in his sleep.

Barama and Laindjung myths The Barama and Laindjung myths from Arnhem Land are Yiritja moiety myths which are different from the myths of the complementary Duwa moiety in that they are about ancestral spirits who came from the land rather than the sea. In fact the moieties reflect the division of the Arnhem Land people, the Yolngu, into land and sea people.

Barama emerged from a waterhole at a place called Guludji near the Koolatong with tresses of freshwater weeds clinging to his arms, carrying special wooden sacred emblems called rangga (similar to tjuringa) which are made from the trunks of saplings and then are decorated. The weeds were not really weeds, but special ceremonial armbands with long feather pendants attached to them. His whole body was covered with watermarks, forming all the patterns and designs which he eventually passed on to the various Yiritja moiety groups, or clans. Barama brought to the Yiritja moiety their sacred objects and designs.

The other cultural hero, Laindjung, emerged at a place called Dhalungu about the same time as Barama. His body was covered with watermarks but he carried no sacred objects. He walked to Gangan where he met Barama and they called the ceremonial leaders of the Yiritja together to perform and then reform their ceremonies.

Barama and Laindjung were similar to missionaries preaching a new religious belief and passing on or changing ceremonies and giving out sacred objects and designs. Barama stayed in one place and left most of the work to Laindjung. He ordered that the sacred objects should be kept from the sight of women and children. Laindjung did not worry about this and openly displayed them and sang the sacred songs in everyone’s hearing. Then the elders decided to get rid of the heretic. Near Tribal Bay, they ambushed him, climbing trees and casting spears down. Laindjung kept on singing. He sank into a swamp, then re-emerged and walked towards Blue Mud Bay where he turned himself into a paperbark tree, called dhulwu.

See also North-eastern Arnhem Land.

Bardon, Geoff See Papunya.

Bark paintings Putting designs on bark is but a way of passing them on to the next generation. The same designs are used in body painting, on hollow log coffins and in ground sculptures. The designs often have their origin in the sacred and come directly from the cultural heroes. All Aboriginal art that is termed ‘traditional’ is spiritual in that as the artist works he or she is conscious of the spiritual presence and power of the ancestral being whose story is being told or incidents from whose life are being depicted.

The abstract cross-hatched designs which are natural features of many bark paintings are symbolic of a certain area or feature which came from the Great Ancestors themselves. For example Luma Luma the giant, who figures prominently in the Mardayan ceremonies at Oenpelli in Arnhem Land, cut criss-cross patterns into his flesh, and these are used today in ceremony and also as designs on the bark paintings from this area.

Until recently, the artists used natural red and yellow ochres, white kaolin or pipeclay and black manganese or charcoal. These colours are applied to sheets of bark which have been cured and straightened over a fire.

Bark painting was once practised by many Aboriginal groups, but since the invasion the tradition has lapsed in most parts of Australia. Today the most vibrant expression is in Arnhem Land. There are different styles of painting here. The artists of west Arnhem Land, which is centred around Oenpelli, the Liverpool and Alligator rivers and the Croker and Goulburn islands, create works which are related to the rock paintings which abound in the area, some fine examples of which may be seen in the cave galleries found in Kakadu National Park. There are two main types of painting, both of which are figurative. One is the so-called ‘X-ray style’, in which the ritually significant internal organs of various animal species are depicted. The second style is of spirits such as the stick-like mimi spirits.

Central Arnhem Land stretches from east of the Liverpool river and includes the settlements of Maningrida, Ramingining and the island of Milingimbi. Here the paintings are divided into a number of panels, much in the style of a storyboard or comic strip. The most common themes are episodes from the song cycles of the Wawilak sisters and Dhanggawul. North-eastern Arnhem Land includes the area around Yirrkala and a number of islands, including Galiwinku (Elcho Island), and their styles are characterized by tight geometric compositions and crosshatched patterns of great intricacy.

The Tiwi people live on Bathurst and Melville Islands off the northwest coast of Darwin and most Tiwi art is concerned with the Pukamani funeral ceremonies, the elaborate and lengthy ceremonies which involve the erection of carved posts similar to totem poles (see Pukamani burial poles). Paintings are usually non-figurative, but sculpture is important here owing to the use of sculpture in the funeral ceremonies. The sculptures are usually of Purukupali, his partner Bima and Tokumbimi the bird, and the accompanying myth relates how death came to the Tiwi. See Curlews; Mudungkala; Pukamani funeral ceremonies.

See also Bark huts and shelters; Ground paintings; Papunya Tula art.

Bark huts and shelters Bark huts and shelters were perhaps the most easily erected dwellings of Aboriginal people. Depending on the environment, dwellings could be either simple constructions of sheets of bark propped up on a framework; substantial stone houses, as in chilly Victoria; sturdy miyas (or miyu miyas), sturdy dwellings constructed of boughs and leaves in an igloo shape, as in Western Australia; or a bark or palm frond hut built on a raised platform to escape the floods of the rainy season in tropical Australia.

There is a Dreamtime story from the Wik Munggan people about the Bush-nut husband and wife who constructed one of the first, if not the first hut when the rainy season caught them in the open. Mai Maityi (Bush-nut) husband and wife travelled upriver, hunting and gathering as they went along. The stormy season came on them and they quickly began to cut sheets of tea-tree bark and lay them on the ground. After this, they cut stakes and placed them in the ground in a circle and tied their tops together. After this, they tied them all around and covered the framework with the sheets of bark. They lit a fire inside and took in their food. The rains came, but they were dry and snug inside.

Barra See Monsoon.

Barrier Reef The Barrier Reef, lying off the northern coast of Queensland, is one of the wonders of the world. The Aboriginal people who live along the coast have passed down stories about when the line of the Barrier Reef was the shore line and when the waters arose.

In the past a man, Gunya, and his two wives were travelling by canoe. They stopped to fish and caught a fish which was taboo. This resulted in a tidal wave arising and rushing towards them. Gunya had a magic woomera or spear thrower, an instrument which gives the spear added impetus, called Balur and this warned them of the danger. Gunya placed the magic woomera upright in the prow of his canoe and it calmed the seas enough for them to reach the shore. They hurried towards the mountains and the seas followed them. They reached the top of a mountain and Gunya asked his wives to build a fire and heat some large boulders. They rolled the hot stones down at the advancing sea. It stopped there, but never returned to its original home.

Barrukill See Hydra.

Bar-wool See Yarra river and Port Phillip.

Baskets and bags Aborigines’ baskets are important containers. Although they are often called dilly bags, they are more like baskets than bags, in that they are semi-rigid, unlike the string bags which are also made. Small baskets are used by men to carry sacred objects and in Aboriginal mythology they are used for such things as the storing of winds or water. Bags were also made from kangaroo skins and were used for storing water. In some stories it is the piercing of a skin bag which results in floods.

There is a central Australia myth about two brothers, one who was prudent and made provision for the future by making a kangaroo skin bag and filling it with water, and the other who did not. The prudent brother refused to share his water with the other when a drought came. He left his bag and went off to hunt. The other brother, maddened by thirst, seized the bag greedily and spilt the water. It gushed out across the sand. The prudent brother saw what was happening and rushed back to save what water he could, but he was too late. The water continued gushing out and filled the hollows and a depression which became part of the sea. Both brothers were drowned in the flood. The birds became alarmed at the spreading flood and attempted to build a dam. They used the roots of a kurrajong tree and this tree became known as the ‘water tree’. In times of drought, its roots hold water longer than other trees and can be used as an emergency water supply.

See also Pukamani funeral ceremonies.

Bathurst Island See Tiwi people.

Beehive The Beehive constellation was Coomartoorung, the smoke of the fire of Yuree and Wanjel (Castor and Pollux), two hunters who pursued, caught and then cooked Purra the kangaroo (the star Capella). When the Beehive disappeared from the sky, autumn had begun.

See also Two Brothers.

Bellin-Bellin Bellin-Bellin the crow is a moiety deity, or ancestor, the opposite to Bunjil the eaglehawk. There are many stories of their rivalry. Eaglehawk is a much more sober bird and Crow is renowned for his cunning – though one must be aware from which side the information is coming. A person belonging to the Eaglehawk moiety would tell stories in which Crow would be seen in a bad light and vice versa.

See also Bunjil; Crow; Eaglehawk and Crow.

Bennell, Eddie (?-1992) The late Eddie Bennell was a Nyungar story-teller from Brookton in the south west who left only a few stories behind. His legacy was seen in Perth when his opera My Personal Dreaming was staged in 1993.

Bennett’s Brook Bennett’s Brook is a stream near Perth, Western Australia, which is sacred to the Wagyal or rainbow snake. It is an important sacred place to many Nyungar people.

See also Bropho, Robert.

Berak, William William Berak was an elder of the Koori people of Victoria. He lived in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Through his efforts many of the traditions of the Koori people were passed down. The grave of this great elder is at Healesville, near Melbourne.

Berrwah See Grasshouse mountains.

Bhima See Bima.

Biame (or Baiame, Byamee) Biame the All-Father is perhaps the most important deity of the present-day Aboriginal communities in the south-eastern region of Australia and the present mythology has taken into it elements of Christianity.

In the versions of the myth which are told today, Biame is a true creator-god. He experimented first in creating the animals, then used them as models in attempts to create humankind. In the Dreamtime, animals were self-conscious and thus had all the discontents of humankind. Kangaroos became ashamed of their tails; fish felt they were imprisoned in water; birds wanted to be like the kangaroos and insects to be larger than they were. Eventually, Biame gathered all the animals together in a cave, took out all their desires and placed them in his new creature: a human being. Thus the animals lost their longings and desires. Men and women alone found themselves the discontented guardians of creation, under the care of the All-Father, who lives up in the sky world and gazes down upon his creation. The Southern Cross is the visible sign that he watches over humankind and protects us as well as punishing us when we break his laws. Biame created the laws by which humankind are meant to live; he also created the first bull-roarer (which when swung represents his voice) and gave the man-making ceremonies to the Aboriginal communities of south-eastern Australia. His chief wife was the All-Mother Birrahgnooloo.

See also All-Fathers; Boro circles; Crow; Curlews; Ground carvings and sculptures; Kuringgai Chase National Park; Marmoo; Narroondarie; Rainbow snake; Rock engravings; Sleeping giant; Southern Cross; Unaipon, David; Yhi.

Bibbulmum My people, the Bibbulmum, occupy a corner of south-western Australia and were once made up of a number of groups having different dialects of a single language and similar laws and customs. When the British invaded and settled Western Australia, the tribal basis of our communities was destroyed, especially with the massacre at Pinjarra when the resistance of the people was shattered (see Yagan). We have now coalesced into a single people made up of a number of extended families based on the old tribes. We now call ourselves Nyungar, which simply means ‘the people’.

See also Conception beliefs; Crow; Dogs; Dreaming tracks; Hair string; Seasons; Trade; Willy wagtail; Yagan; Yamadji.

Bidjigal See Eora tribe.

Bildiwuwiju Djanggawul’s elder sister. See Djanggawul and his two sisters myth.

Bildiwuraru See Djanggawul and his two sisters myth.

Bilyarra See Mars.

Bima See Curlews; Mudungkala.

Bimba-towera the finch See Echidna.

Binbeal See Bunjil.

Bindirri, Yirri (Roger Solomon) Yirri Bindirri is the son of Malbaru, or James Solomon, and they are both elders of the Ngarluma people of Western Australia. They are well known for striving to keep alive the traditions of their people. In the film Exile and the Kingdom, the elders explain the mythology which binds them to their country around Roebourne in Western Australia.

Bingingerra the giant freshwater turtle See Yugumbir people.

Birbai See Bundjalung nation.

Birraarks See Shamans.

Birrahgnooloo See All-Mothers.

Birrung See Bundjalung nation.

Black (or charcoal) is an important colour in Aboriginal paintings and also is used as a medicine. It is a sacred colour of the Yiritja moiety of Arnhem Land.

See also Bark paintings; Red, black, yellow and white.

Black flying foxes See Flying foxes.

Black Swans See Altair; Bunjil; Murray river.

Blood Bird See Yugumbir people.

Bloodwood tree See Djamar; First man child; Menstrual blood; Moiya and paka paka; Tnatantja poles; Yagan.

Blue Crane See Narroondarie.

Bodngo See Thunder Man.

Bolung Bolung is another name for the rainbow snake among the people of the Northern Territory. Bolung takes the form of the lightning bolt which heralds the approach of the monsoon rains. He is a creative and life-giving deity and, like many of these serpent deities, inhabits deep pools of water.

Bone pointing The bone pointing ceremony in variations is found all over the continent. It is used to kill a person from a distance. The bone is usually made from the femur of a kangaroo or a human, the most powerful pointer being one from the leg of a former shaman.

The ceremony must be performed by a shaman, usually assisted by a colleague. The bone is pointed in the direction of the intended victim. It is said that a quartz crystal passes from the point and through space into the victim. The connection is made and the soul of the victim is caught and drawn into the bone through the power of the shaman. Then a lump of wax or clay is quickly attached to the point. This lump, energized by a spell, is to stop the soul escaping from the point. When the soul is caught, the bone is buried in emu feathers and native tobacco leaves. It is left in the earth for several months. At the end of this period it is dug up and burnt. As the bone burns, the victim burns along with it, becoming progressively sicker. When the bone is completely consumed, he is dead.

Boomerang The boomerang is more than a bent throwing stick that returns. It was first fashioned from the tree between heaven and earth; it symbolizes the rainbow and thus the rainbow snake; and the bend is the connection between the opposites, between heaven and earth, between Dreamtime and ceremony, the past and the present.

In many communities the boomerang is a musical instrument rather than a weapon. Two boomerangs clapped together provide the rhythmic accompaniment in ceremonies, thus creating the connection between dance and song.

See also Gulibunjay and his magic boomerang.

Boonah See Narroondarie.

Bootes The Bootes constellation, or, rather, a star in Bootes, west of Arcturus, was Weet-kurrk; daughter of Marpean-kurrk (Arcturus) according to the Kooris of Victoria.

Bornumbirr See Morning Star.

Boro circles The boro circles or grounds are the sacred ceremonial grounds of the Australian Aborigines. In the eastern regions they consist of a larger and smaller circular ground connected by a path. The smaller boro ground is said to represent the Sky-World where Biame has his home. It is forbidden to noninitiates. The larger ground represents the earth and is public. The ceremonies performed there are less secret.

Boro circles occur all over Australia and have different names in the different languages. In regard to these circles, Bill Neidjie says, ‘This “outside” story. Anyone can listen, Kid, no matter who, but that “inside” story you can’t say. If you go in a ring-place, middle of a ring-place, you not supposed to tell im anybody ... but, oh, e’s nice.’

Borogegal See Eora tribe.

Borun the pelican See Frog.

Bralgu Bralgu is the Island of the Dead according to the Aboriginal people of Arnhem Land. It is said that after three days the newly deceased is rowed in a canoe by Nganug, an Aboriginal Charon, across the ocean to the Island of the Dead to be greeted by other departed souls.

It is said that every day, shortly before sunset, the souls at Bralgu hold a ceremony in preparation for sending the Morning Star to Arnhem Land. During the day and the greater part of the night, the Morning Star is kept in a dilly bag and guarded by a spirit woman called Malumba. The souls and spirits hold a ceremony during which much dust is kicked up. This brings the twilight and then the night to Arnhem Land. When the time approaches for the Morning Star to begin its journey, Malumba releases it from her bag. On release, the Morning Star rises up and rests on a tall pandanus palm tree, the Dreaming tree of life and death. From there, it looks over the way it is to go, then rises, hovers over the island and ascends high into the sky. Malumba holds a string to which the star is attached, so that it will not run away. When morning comes, Malumba pulls it back and puts it in her bag.

See also Thunder Man.

Bram-Bram-Bult See Centaurus; Southern Cross; Two Brothers.

Bran Nue Dae Bran Nue Dae is a musical put together by Jimmy Chi and the Kuckles Band of Broome. It details the adventures and misadventures of Willie, a young man, and his mentor, Uncle Tadpole, and gives an insight into the modern lifestyles of Aboriginal people in Western Australia. It has been enormously successful throughout Australia.

Brisbane See Dundalli; Grasshouse mountains; Platypus; Rainbow snake.

Brolga See Duwa moiety.

Bropho, Robert Robert Bropho is an important member of the Nyungar people who has led the fight to protect the sacred places in Western Australia. He lives in Lockridge on the outskirts of Perth, close to Bennett’s Brook, an important Dreaming place of the Nyungar. He has made films and written books to highlight the injustices of our people and to protect our sacred places.

Buda-buda See Mopaditis.

Bull-roarer A bull-roarer is a shaped and incised oval of wood, to one end of which is fastened a string. It is rapidly swung in the boro ground ceremonies (see Boro circles). There are many varieties of bull-roarer and the sacredness of the object varies from area to area. When it is incised with sacred designs it becomes a sacred object known as a tjuringa or inma. In some places it may be seen by everyone; in others, especially in the south east, it may only be seen by the elders or initiated men. In some areas, northern Queensland for example, a larger bull-roarer is considered male and a smaller one female. When swung, they are said to be the voices of male and female ancestors, who preside over the sacred ceremonies of initiation. The bull-roarer among the Kooris of south-eastern Australia was first made by Biame and when it is swung it is said to be his voice.

See also Duwoon; Moiya and pakapaka.

Bullum-Boukan See Trickster character.

Bullum-tut See Trickster character.

Bumerali See Universe.

Bundjalung nation The Bundjalung people are a large Aboriginal nation, a federation of a number of groups of clans which occupy the land from the Clarence river of northern New South Wales north to the town of Ipswich in southern Queensland. The names of these groups are Aragwal, Banbai, Birbai, Galiabal, Gidabal, Gumbainggeri, Jigara, Jugambal, Jugumbir, Jungai, Minjungbal, Ngacu, Ngamba, Thungutti and Widjabal. Their ancestors are the three brothers, Mamoon, Yar Birrain and Birrung, who are said to have come from the sea. The brothers, along with their grandmother, arrived in a canoe made from the bark of a hoop pine. As they followed the coastline, they found a rich land sparsely populated. They landed at the mouth of the Clarence river and stayed there for a long time, then, leaving their grandmother behind, they continued on in their canoe heading up the east coast. At one place they landed and created a spring of fresh water. They stopped along the coast at various places and populated the land. They made the laws for the Bundjalung and also the ceremonies of the boro circle.

It is said that the blue haze over the distant mountains, especially in spring, is the daughters of the three brothers revisiting the Earth to ensure its well-being and continuing fertility.

See also Bundjalung National Park; Dogs; Duwoon; Ginibi, Ruby Langford; Gold Coast; Great battles; Jalgumbun; Terrania Creek basin and cave; Tooloom Falls; Woollool Woollool.

Bundjalung National Park Bundjalung National Park in northern New South Wales includes Dirrawonga, a sacred goanna site now called Goanna Headland.

In the Dreamtime, Nyimbunji, an elder of the Bundjalung nation, asked a goanna to stop a snake tormenting a bird. The goanna chased the snake to Evan’s Head on the coast where a fight ensued. The goanna took up the chase again and went into the sea. It came out from the sea and became Goanna Headland.

The goanna is associated with rain and there is a rain cave on the headland where the elders of the Bundjalung people went in the old days to conduct ceremonies for rain.

See also Bundjalung nation; Rain-making.

Bungle Bungles The Bungle Bungles in Western Australia is a taboo area. It covers an area of 700 square kilometres with sheer cliffs, striated walls and deep gullies. The formations were considered to be inhabited by forces inimical to life and so no Aborigines ever went there.

Bunitj See Kakadu National Park; Neidjie, Bill; Seasons.

Bunjil Bunjil the Eaglehawk ancestor is a creator ancestor of immense power and prestige to the Kooris, the modern Aboriginal peoples inhabiting what is now the state of Victoria. In the old days he was a moiety deity, or ancestor, of one half of the Kulin people of central Victoria.

Bunjil had two wives and a son, Binbeal, the rainbow, whose wife was the second bow of the rainbow. He is said to be assisted by six wirnums or shamans, who represent the clans of the Eaglehawk moiety. These are Djurt-djurt the nankeen kestrel, Thara the quail hawk, Yukope the parakeet, Dantum the parrot, Tadjeri the brushtail possum and Turnong the glider possum.

After Bunjil had made the mountains and rivers, the flora and fauna, and given humankind the laws to live by, he gathered his wives and sons, then asked his moiety opposite, Bellin-Bellin the crow, who had charge of the winds, to open his bags and let out some wind. Bellin-Bellin opened a bag in which he kept his whirlwinds and the resulting cyclone blew great trees into the air, roots and all. Bunjil called for a stronger wind and Bellin-Bellin obliged. Bunjil and his people were whirred aloft to the sky world where he became the star Altair and his two wives, the black swans, the stars on either side.

See also Eaglehawk and Crow; Melbourne.

Bunjil Narran See Shamans.

Bunuba people The Bunuba people live in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and their country is below that of the Worora, Wunambul and Ngarinjin peoples. Their main ancestors are Murlu the kangaroo and the Maletji dogs, who gave them their laws and customs as well as their land, culture, weapons, songs and ceremonies.

During the resistance led by Jandamara against the invaders in the late nineteenth century, the Bunuba people suffered terribly with men, women and children being massacred wherever they were.

See also Dogs; Woonamurra, Banjo.

Bunurong people See Melbourne; Yarra river and Port Phillip.

Bunya the possum See Centaurus; Southern Cross.

Bunyip The Bunyip, a legendary monster, supposedly of Aboriginal origin, appears to be an instance of mistaken identity. It seems to be the Meendie giant snake of Victoria who lived in the waterhole near Bunkara-bunnal, or Puckapunya. The attributes of the Bunyip are those of the rainbow snake.

Buramedigal See Eora tribe.

Burnum Burnum (1936-) is an elder of the Wurandjeri people of southern New South Wales. He is a story-teller, actor and worker for his people. In 1988 he went to England to claim that country on behalf of all Aboriginal people as compensation for the wrongs inflicted on our people by the invaders from that island. He has become well-known for popularizing a dolphin Dreaming ceremony.

Burrajahnee See Dogs.

Burrawungal See Water sprites.

Burriway the emu See Great corroborees.

Burrup peninsula Burrup peninsula in the Pilbara was owned by the Yaburara people. In the nineteenth century they were completely wiped out in what is called the Flying Foam Massacre. Their land is now cared for by the Ngarluma people.

The peninsula is a natural gallery of figures pecked into the hard rock. There are over 4;000 motifs in the area. One of the most interesting sites shows figures climbing (perhaps away from a flood?) Parraruru (Robert Churnside), now deceased, relates a flood story of this region. Pulpul, Cuckoo, was then a man and lived on the peninsula. The sea began rising. He thought what to do about it. It rose and rose, then he said ‘Down, down.’ It went down and he became a bird just at that moment.

In another story from the neighbouring Jindjiparndi people, the seas rose until they flooded the land 30 miles inland before being stopped by Pulpul. It is said that mangroves still grow there.

Bush-nut husband and wife See Bark huts and shelters.

Byamee See Biame.

Byron Bay Byron Bay in northern New South Wales is close to an important woman’s fertility site situated at Broken Head.

Lorraine Mafi-Williams, an important woman story-teller and custodian of culture, lives in the town.