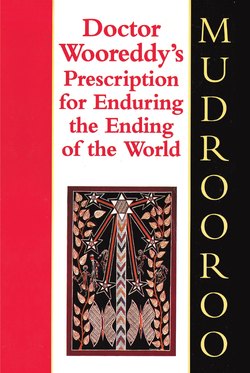

Читать книгу Doctor Wooreddy's Prescription for Enduring the End of the World - Mudrooroo - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 The Omen

ОглавлениеI

Wooreddy as a child and a young man belonged to Bruny Island: two craggy fists of land connected by a thin brown wrist. It was separated from the mainland by a narrow twisting of murky water. His island home abounded with wallaby and each tree held a possum. All along the rocky female coast-line, clinging in mute desperation to the last vestiges of the land, shell- and crayfish hung waiting to be gathered. Wooreddy belonged to a rich island, but the surrounding sea was dangerous and filled with dangerous scale fish. Not even women were allowed to gather these creatures. It was evil luck to see one. They were taboo, for unlike the denizens of the real world, they swam in a different medium and never needed to feel or touch the earth. To them the land was death, just as to the Bruny Islanders the sea was death. This belief lay in Wooreddy’s mind as he wandered by himself in the direction of a beach.

Around him lay the summer, peaceful and sun warm on his skin, A breeze touched his nostrils with the different smells from the open and closed bush. With it came the slight smell of humankind. His tiny feet drifted him along towards a narrow bay arcing between two long fingers of points. Living on an island, he was never very far from the sea and a favourite spot was the beach toward which he was moving. Suddenly the breeze switched direction to blow in strongly from the ocean. The salt-smell caused him to think, of that thing, neither male nor female, which heaved a chaos threatening the steadiness of the earth. It heaved like some huge wombat, and unlike the flowing darkness beyond the campfires, could never be penetrated. It stood away from humankind. Wooreddy was only a ten-year-old boy, but he thought such thoughts. Born between the day and night. He had a fascination for things that lurked and threatened. He walked onto the beach thinking of charms and omens, mysteries and things hidden in the dark cave of the mind.

Though only a small boy, Wooreddy already had wriggled many times to the side of the few irascible old men as they sat theorising on life and its mysteries. On these occasions he had to pretend to make himself as tiny as an ant so as not to be noticed and chased away. Somehow he almost always managed to stay, intently listening with a child’s mind which missed concepts but caught mysteries. They fell into his ears like raindrops and filled his head with things beyond his years. One such drop was Ria Warrawah which, or who, seemed to infest and affect all existing things. It, or he, or she lurked ready to strike down the unwary and on rare occasions hand power to the wary. This thing or creature was held at bay by the Great Ancestor who lived in the sky as a star. When Ria Warrawah became too strong and threatening, he subdued it with long flaming spears.

Sometimes the old men sat talking far into the night and Wooreddy stayed with them either sleeping or listening. Most times he missed much of the conversation as it meandered towards the dawn. It drifted in the darkest part of the night and became murky with Ria Warrawah. They discussed the taboo placed on its manifestation as a fish. To touch one meant death; to see one meant the itching sickness. Only powerful spells and charms could stop any harm. They detailed the forms and powers of this ‘thing’. He, or she, or it was the sea and lived in the sea from which it sent manifestations as well as tidal waves to harm the land and those who lived on the land. But try as it might, it was held at bay by Great Ancestor. He had sent himself (or part of himself) crashing into the sea just off the eastern coast of Bruny. There he stood protecting the island. He also had sent them fire so that they could see in the darkness.

Wooreddy listened or slept while the information built into the foundations on which the adult character of the future Doctor Wooreddy would be erected. The child had already learnt that the ocean must be confronted side-on and not directly. One had to be always alert for attack. But this day the boy felt so overwhelmed by the delightful charm of the weather that he began leaping and bounding along the beach like a kangaroo. He gave an extra-long bound and landed on something slimy, something eerily cold and not of the earth. Desperately he sprang away as his eyes clenched shut to keep out the horrible sight. He marched seven steps chanting a spell, then gave a yelp of despair. The last step had brought his big toe against something slimy, something eerily cold and not of this earth – and worse, it was spiky and wriggled. It was alive! He began to tremble violently. Ria Warrawah wrapped him in a transparent mist. He was lost! His hands shut out the world as his mind desperately searched through remembered snatches of half-understood conversations in an effort to find a potent protection spell. He tried a string of words. As the last one left his lips, there came a strange moaning from the sea, then gruff voices speaking in strange tongues which were followed by a sharp crack that made the water heave and lap at his feet. By magic his eyes clicked open to focus in a fixed stare on what had come from the sea. It was an omen, an omen, he knew – but what came from the ocean was evil, and so it was an evil omen. His eyes remained fixed on it. Shapes of thick fog had congealed over dark rocks, or a small island which floated a travesty of the firm earth.

Another boy would have turned tail or collapsed in a quivering heap of shock, but Wooreddy had been born for such sights. He watched the fog patches shift as they tugged the tiny dark island along. Such visions were rare and set a person apart. He had been selected and set apart. The future doctor felt the strangeness fill him. It became a part of him. Now remembered voices of the old men began murmuring in an effort to explain the unexplainable:

‘Once in the time of our grandfathers and before the birth of our fathers, a small piece of darkness, fashioned by the very thought of Ria Warrawah, came floating along on the sea. Ria Warrawah manifested himself as a cloud and pulled the island along. He pulled to Adventure Bay and left it there. Our grandfathers watched from the shore. They saw the black sticks by which Ria Warrawah had held it as he pulled it along. Then a piece of the island broke away and came crawling across the sea towards them. Our hidden grandfathers watched on. The creature touched the land. It carried pale souls which Ria Warrawah had captured. They could not bear being away from the sea and had to protect their bodies with strange skins. They spoke and the sounds were unlike any that had been heard. Our grandfathers remained hidden and after a time the creatures mounted their strange sea thing and went back to the dark island.’

This account explained the ships sailing past to form the first European settlement on the Derwent River, but it did not explain Wooreddy’s enlightenment which he now endured. Nothing from this time on could ever be the same – and why? Because the world was ending! This truth entered his brain and the boy, the youth and finally the man would hold onto it, modifying it into harshness or softness as the occasion demanded. His truth was to be his shield and protection, his shelter from the storm. The absolute reality of his enlightenment took care of everything. One day, sooner rather than later, the land would begin to fragment into smaller and smaller pieces. Clouds of fog would rise from the sea to hide what was taking place from Great Ancestor. Then the pieces holding the last survivors of the human race would be towed out to sea where they would either drown or starve.

The boy stood in a trance and learnt that he would live on to witness the end. He had been chosen and would endure through the power of his Truth. It was a charm of awful power. He received it in this initiation and then it retreated to live on in a corner of his mind. He awakened with his back to the sea. The sun dissipated the fog, the breeze turned to flow from the land, bringing the scent of humankind. The smoke of the campfires awakened his hunger. His lithe, brown body charged off to the nurturing warmth of his mother. She sat mending a basket. He begged her for food and she gave him the tail of a large crayfish. He loved her for it.

II

Wooreddy waddled his way towards adulthood in an awful world that became less and less familiar. Before, uneventful time had stretched back towards the known beginning. Now, it seemed that something had torn the present away from that past. Many people died mysteriously; others disappeared without trace, and once-friendly families became bitter enemies. Night after night the piercing whistles of Ria Warrawah shrieked from the hidden recesses of the forest. No one could understand what was happening. Still the people endured and tried to live as they always had lived.

Wooreddy grew and reached puberty. Jokes were made about his sprouting pubic hair and the sudden uncontrolled erections which showed his manhood. Then, in the dead of night, the older men grabbed him and hustled him through just a few short metres of darkness to where a campfire gleamed. Once it would have been further away and hidden, but times had changed. His uncles held him down while a stranger thrust a firebrand into his face. Another man chanted the origin of fire and why it was sacred for him. Fire was life; fire was the continuation of life – fire endured to the end. He came from fire and would return to fire. One day it would take his spirit to the Islands of the Dead where he could live happily stuffed with plenty of wallaby, kangaroo, possum and seafood brought by his loving mate. But this was not all, for on those islands grew the cider trees exuding litres of sweet intoxicating sap which could fly his soul to where Great Ancestor’s campfire flamed the sky with light. There he could live on with Great Ancestor in bliss. Fire was a gift from Great Ancestor and Wooreddy had been selected as one descended from that gift. Now while he lived he had to ensure that fire lived. They whispered his secret name, Poimatapunna (Phoenix), then detailed the coming of fire:

‘Fire was sent to us by Great Ancestor. He gave it to two birdmen to bring to us. Long ago, the grandfathers of our grandfathers saw them standing on top of a high hill. They stared up at the strangers. They saw them raise their hands. Burning brands fell from them and among our people. The very earth began to burn and our ancestors fled across a river to escape. Much later they returned to their land and walked over the burnt and blackened earth. Many burnt animals lay here and there. They tasted some and found that they were good to eat. Then they knew that fire was good and from that day we have used it. And when we move over our land we burn it off in remembrance of that time. Never forget that your own campfire is descended from that first fire. It is a living sign of our connection to Great Ancestor and his many fires flickering in the sky...’

The recitation hesitated and the youth felt the burning brand pressed to his breast. It hurt, it hurt like – what else? – the touch of fire. He wanted to shout out his pain. Instead he gritted his teeth against it and endured the fire eating into his flesh. At long last the brand was withdrawn. His throbbing flesh throbbed in time to the continuing chant. Would the searing pain ever go away!

‘Those two birdmen, those two messengers from Great Ancestor, did not fly off into the sky. They stayed on in our country and you will see the marks of their camping places. Near the Lungannaga river two women dived into the water for mussels. They did not know that below the surface lurked Ria Warrawah in the shape of a giant stingray. From his hiding place in a dark hole among the rocks, he watched those women. They swam down. They were very near. He dashed out. He lashed out with his spear. He stabbed and stabbed; he cut and cut; he thrust and thrust; he pierced those women through and through...

Wooreddy, thoroughly miserable from the aching of the burn, now had to endure a series of parallel slashes across his chest. It was little consolation that the cuts from the sharp shell piece did provide a contrast to the dull throbbing. He wished to be anywhere but where he was. In an effort to see the blood trickling down his ribs, he rolled his eyes as the myth continued to unfold.

‘The two birdmen came to the shore. They saw the great stingray basking in the shallows, gloating over his deed. He did not enjoy his triumph for long. They crept to him; they fought with him; they wounded him; they killed that evil thing!’

The miserable youth had to undergo further torments as the stingray was disposed of. To add to the burnt patch in the centre of his chest and the seven cuts on the right side, three more were engraved on the left. Later on in life he could earn four more, but now this was all that he had to endure – or at least he hoped so, for perhaps his knowledge of the ceremony was faulty, or a variant had been used. He eased out a sigh of relief as the myth flowed on.

‘From the water, they took those two dead women. They were messengers from the Great Ancestor and had no fear of it. They lay the two women upon the ground and built a fire between them. Then they opened their chests and put into the chest-cavity some blue ants.’

Wooreddy shuddered as someone gently touched his wounds. He relaxed knowing that an ointment of fat and ash was being smeared over them.

‘The ants stung those two women into life. They moved, and moved again as the ants stung them again, as the birdmen sung life into them. Then the two strangers filled the holes in the women’s chests with mud and pressed the flesh together. The holes were no more. They fixed the women’s wounds in the same way, and they were whole.’

The youth gave a slight smile as soothing river mud was put over his own wounds. The ceremony was almost at an end.

Ria Warrawah raged at being deprived of two victims. He rose, he rose as a vast fog, to race in from the sea and towards the two birdmen. It might have been fast, but those two were faster. Ria Warrawah extended almost to them. Up they flew with those two women. Up they flew, and you can see them in the sky to this day.’

The ceremony ended at dawn and Wooreddy retreated into the bush to stay by himself while his wounds healed. He accepted the solitude as he had accepted the burning and slashing. In these days of tribulation and when the world was ending, tradition and custom were comforts.

When Wooreddy returned to the camp, he came as a man permitted to express the feelings of a man. Sex awareness often hit him like a blow from a club and he had, at times, to command himself not to proposition other men’s mates. Honour kept him from breaking the law and intriguing for relief. But his eyes often followed the swaying hips of a woman. Perhaps he could seek a mate from some stranger-community. This was permissible and some of the other men had foreign wives. He observed these matches and was deterred. The men, unlike those who married women from the customary groupings, seemed like shellfish collected in a basket. Foreign women expected their men always to return laden with game from the hunt. They expected their menfolk to be always attentive and when they quarrelled, the wife instantly threatened to return to her own country or to find a better man. Seeing this, and seeing it too often, Wooreddy put the idea of a foreign wife from his mind and began to look for a local girl for a mate. Or rather his father did the looking, while he suffered the pangs of lust and waited for the event to happen.

Women and marriage were not the only things he saw with that detachment which had become a mannerism from that day, seven years ago, when the omen had forced itself upon him. He watched a man burn his mate. He squatted just beyond the light cast by the fire to observe the cremation. The woman had been murdered by ghosts and this made her funeral of special interest. Everything had to be done just right, if the spirit, tormented by the loss of a young and healthy body, were to be sent away towards the Islands of the Dead. The family gathered the material for the pyre. The father belonged to a different clan from Wooreddy. One in which he could marry, he thought, as he watched the three daughters working. Moorina and Lowernunhe were past puberty and taken, but the third one was only twelve and possibly still unattached. She was a female with a strong will. Everyone had become aware of this when, as a child of five, she had dived after her sisters into the surf and almost drowned. He knew that a great future as a provider had been predicted for her – and much sorrow for her mate!

Wooreddy dressed his hair as he waited. He rubbed a plain grease over it, then searched his chin for any lengths of hair growing on his cheek. He found one or two and pulled them out. Dawn turned into morning, and the family members probed further into the bush for timber. Finally, Mangana, the father, determined that enough had been collected. He stood beside a shallow square dug into the earth and muttered a few incantations before beginning to stack the logs up in the form of a hollow cube. When he reached a metre and a half, he stopped and began filling it with twigs, leaves and bark. Wooreddy noticed that the structure had begun to sag at one corner, and sighed. The old ways were losing their shape and becoming as the cube. Mangana, he had heard, on hearing of his wife’s murder, had only shrugged his shoulders and muttered: ‘It is the times.’ His words summed up the general mood of the community. No one had any trust in the future and they accepted a prophecy that passed among them: fewer babies would be born to take the place of the adults dying ever younger; fewer babies to be born, to be weaned, to die – and this meant fewer mature adults to keep and pass on the traditions of the islanders. Thus it was, and it was the times. Everyone knew this and accepted it. Wooreddy alone knew more. He knew that it was because the world was ending.

From a bark shelter hidden beneath the down-hanging branches of an ancient tree, the husband carried out the corpse of his wife. The three daughters began snivelling. Wooreddy was impressed by the solemnity of the occasion, by the sight of the man carrying to the fire the dead body of his mate. Mangana gently placed the corpse on top of the pyre. Softly Wooreddy moved closer to see if custom was being observed. The limbs were folded against the trunk and tied there with woven-grass cords knotted in the proper manner. He nodded: it was as it should be. He turned to where Mangana squatted at the fire, poking a long stick into the flame and muttering a short incantation until the end caught. Then he rushed the stick to the pyre and thrust it through the special tunnel which led into the heart of the cube. Tendrils of smoke pushed up past the corpse. A few licking tongues of fire erupted to dance into a hungry red mouth under the spell of the onrushing morning wind. The roaring flames carried the female spirit up and away from the land of the living leaving behind loss and sorrow. Mangana groaned out his pain. His daughters wailed out their pain. One by one the man took up his spears and broke them. It was an abject sign of surrender. One disarmed oneself before an enemy of overwhelming strength and cast oneself on his mercy.

Mangana’s wife had been raped and then murdered by num (ghosts) that came from the settlement across the strait. What had happened had had nothing to do with her, her husband or her children. It had been an act of Ria Warrawah – unprovoked, but fatal as a spear cast without reason or warning. No one could have protected her, and thus Mangana broke his spears and cast the pieces on the blazing pyre. This showed that he, and all who were associated with him, were at the mercy of forces which he could only try and propitiate through magic. He snatched up a sharp pebble and slashed at his chest. Blood dripped upon the earth. He flung drops into the flames. He groaned and raised his lacerated breast to the first rays of the sun. Black blood turned as red as the fire consuming his mate.

This was not the last tragedy Mangana was to suffer, or Wooreddy to witness. More and more people died and the frightened survivors huddled together. Family groupings had been created by Great Ancestor. From the first he had bound individuals together in biological groupings. No one was alone. But that was how it had been. Now some families were reduced to only a single member, and with all their relatives gone they were alone in a country of strangers. Wooreddy found himself in this predicament, but instead of giving way to despair he applied himself to rectify the situation. A thinker with a family was a thinker in custom; a thinker with only his thoughts to keep him company was an outcast. He could not live alone and needed allies. He was drawn to the remnant family of Mangana.

He spent much time sitting with the father. Now that so many custodians of lore had been swept away, Mangana could be classified as an elder. He might have knowledge and Wooreddy, a youth with too big a brain, wanted to get some of it. This, apart from his need of allies, was a strong enough reason to stay close to the older man. But Mangana did not pass on any wisdom. That which he might have once possessed had been destroyed by the times which had personally struck him such a vicious blow that he had been knocked into premature senility. For most of the day he sat and watched the flickering flames of his fire which Wooreddy kept up. He sat subdued while ghosts roamed his land and marked it out as their own. Within and without there was no hope, and sometimes Wooreddy heard him softly moan as he probed the wounds of his sorrow. Too often silence settled on man and youth, and that silence was the brooding of Ria Warrawah. It hung between them that day when the thudding of tiny feet imprinted themselves on it. Wooreddy recognised the feet as those of Trugernanna. As always he was correct. Hunter as well as thinker, he could identify individuals by their footprints. Trugernanna flung her body into the clearing and stood panting before the two men.

Her father slowly lifted his face and asked in a monotone: ‘Why haven’t you collected some food? I’m hungry!’

The child answered in a similar dead voice: ‘Three ghosts came rowing into the bay. They took first and second sister away.’

Mangana looked from his daughter to the youth. He began to speak perhaps with a slight intention of justifying his listlessness and his numb reaction to the loss of his two eldest daughters.

‘Num come; they see what they want; they take it. It is their way. They do not know Great Ancestor and his laws. I remember when I first saw their big catamarans. I did not know what they were, or perhaps I did because they scared me. They scared all of us and they still scare us. We have lived in fear since they came and can do nothing to put an end to that fear. When we first saw them, we talked about them and decided that they were spirits of the dead returning. Soon we found that they were not our dead, but perhaps those of our enemies. They were under the dominion of the Evil One, Ria Warrawah. They killed needlessly. They were quick to anger, and quick to kill with thunder flashing out from a stick they carried. They kill many, and many die by the sickness they bring. Now all I have left is my little daughter. Once nine shared my campfire. Now it is hard to find nine members of my clan. A sickness demon takes those that the ghosts leave alone.’

Wooreddy seized on the last sentence and added it to his own foreboding. The island was haunted and unsafe to humans. He must escape before he became a victim of the demon or the ghosts. He would not delay, and leave today. He would cross over to the mainland and flee far away from the num.

Trugernanna shuffled her feet and coughed for attention. Good or bad news focused attention on the bearer and she wanted the limelight. Without waiting for her father’s permission she began to relate her story. Wooreddy could have ordered her to shut up, but he too wanted to hear the details.

Trugernanna was sitting on the beach watching her two big sisters diving for sea food. Relaxed and happy, they clambered to the top of a rock and stood looking down into the surf breaking at the base. They laughed for they had little fear from the sea. Then around the point came crawling a dinghy. It came to the rock on which the women stood and stopped bobbing up and down a few metres from the base. A lazy oar stroke kept it in position. Trugernanna, watching from the beach, became alarmed, but the women remained on the rock looking down at the three num staring up. Trugernanna reacted to her fright and dashed into the scrub. Safely hidden, she watched on. One of the ghosts held up a piece of soft skin. It was so soft that it fluttered in the breeze. It was of the brightest red she had ever seen. He flapped it, and his gutteral voice grated across the water to her. She listened, all ears, but couldn’t even separate the individual words.

‘Hey, my lovelies, come to our boat. We won’t hurt you. We have this and more like it for you.’

The bright cloth held Trugernanna’s eyes. She turned her gaze on her sisters and saw them look at one another. She guessed that they too wanted the bright skin. Both suddenly sprang from the rock and disappeared under the water. They came up next to the boat, held on to the side and stretched out their free hands. Trugernanna saw the num grab them by the reaching hands and haul them aboard. They screamed, but she did not see them put up much of a struggle. The boat began moving and disappeared from whence it had come. The girl ran off to tell her father.

Both men heard her out. Their bleak eyes stared into the fire as if a solution to their problem rested there.