Читать книгу Book of Indian Beauty - Mulk Raj Anand - Страница 13

Оглавление| 2. BEAUTY AND THE MIND |

She teaches me all her secrets, that it is better to soak our cheeks in snow water, that the powdered root if lemon grass brightens our teeth, that nothing is better than the juice if green strawberries to ripen our breasts; but not the secret if that charm which shines through her like the luster if the pearls on her body.

—AMARU, 8th century

A HIGHLY MENTAL and richly sensuous people, the ancient Hindus insisted that their sensuality be refined with thought.

One of the cardinal principles of health that they elaborated is that there is no dividing line in human personality between the mind and the body. The slightest and most subtle characteristic of the mind of a person, they say, is registered on his or her countenance. The mind is body and the body mind. That being so, they suggest to those who would seek to cultivate beauty, to cultivate a beautiful soul.

To cultivate a beautiful soul is to live in defiance of all that is drab in life. It involves the need to know oneself and one's surroundings. It should be possible for us to comprehend those subtle urges in our nature that incline us to relish the color of a wild flower, the shape of a graceful body, and the tenderness of a lover's feeling. For if we are capable of doing that, we are in a position to understand our ever-changing experience, to foster poise, accept the beautiful, and discard the ugly. It is a continual struggle, of course, constantly to take stock of the world and our emotions about it. But the mental tension that is called "divine discontent" is a state that perhaps best symbolizes what is called happiness.

So the drop of the dew of thy love, which trembles on the petals of my heart, reflects in my love the sky of the soul. (From the Burmese, 19th century)

In certain people, one of the two extremes of human nature, the body or the mind, is unduly emphasized.

The Buddha, for instance, (and Jesus) rejected the feverish, agitated life of the body and achieved such sensitivity that he could weep to see the plough furrow through the ground.

The philosopher Shankaracharya stressed the mind so much that he regarded matter as mere illusion.

The sage-king Bhartihari insisted on alternating the two extremes. He retired to a monastery and became a saint after living a life of complete abandon, but from his hermitage he reverted to his former wild pleasures. Then he returned again to practice asceticism. He always had a horse saddled outside his cell, however, because he never knew when he would feel one or the other of his extreme urges.

The dangers of this extremism are lessened, say the ancient books, by straining after balance or equilibrium. But the actual process of Indian life has been, for the majority of our people, an instinctive one. The controlling function of reason was allowed a high place, save when it was over-zealous in repressing and suppressing the flow of feeling. In this context, of the two ideals of life-ascetic withdrawal and the full life-the latter has been more emphatically practiced.

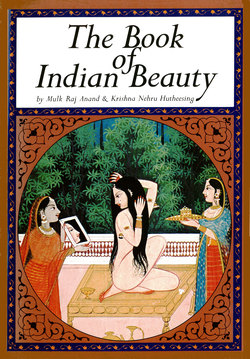

6. A Mogul princess with her maid. Mogul, 1700-1725.

The moral codes were mostly discounted by the people of India, except when the moral laws were convenient or when they were forcibly imposed. The people accepted, for instance, such virtues as the Buddha preached: kindness, generosity, gentleness, the avoidance of anger, hate, pride, jealousy, and sour temper; and they were forced to accept piety. But the general feeling about life as it is actually lived has been that life is an experience that is both good and evil, to be gone through willingly in the illusory world, because we ourselves can make it so by our good and bad deeds, and because it is all experience.

And most of the people gave themselves up to their impulses, lent themselves to the abandonment of ecstasy, and mingled the delicate and sensuous emotions of the heart with the subtleties of the mind; they felt life deeply, and they saw it as a whole.

Our best folk art and literature suggests the hidden forms of passional experience. Our people seem to stride forth exultantly, in their painting and sculpture and poetry, dancing, conscious of the physical delight of moving their legs, conscious of the sun overhead, the earth under their feet, of the whole enchanted atmosphere, abandoned to dreams that are earthly and yet not of the earth. It is a delicious magic, in which a mother suckling a child, lovers embracing each other, a sick man on the verge of death, are all accepted with a tender awareness of the floating and fluctuating quality of existence.

The ways of life which are the lot of busy householders are naturally conducive to rich and vital impulses, and there is an emphasis on this world, on the here-now, in our folk culture, which gives the lie to the idea that we were always a people intent on release from the trammels of life. In fact we are as natural, as sensuous a people by tradition and temperament as any in the world.