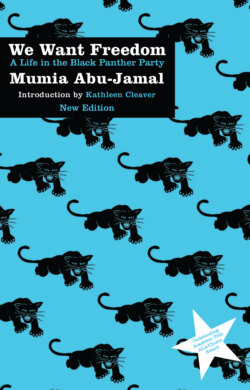

Читать книгу We Want Freedom - Mumia Abu-Jamal - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1. The Beginnings of the Black Panther Party and the History It Sprang From

ОглавлениеChapter One

The Beginnings of the Black Panther Party and the History It Sprang From

I started with this idea in my head, “There’s two things I’ve got a right to, death or liberty.”

—Harriet Tubman, Black Freedom Fighter

The origins of the Black Panther Party seem surprisingly mundane, as we look from the other side of time’s hourglass.

Two relatively poor college students, fresh from meager and uninspiring public schools, seek to join a junior college’s Black student group to give voice to their emergent sense of activism.

They were, on the surface, unremarkable. Two Black men in their twenties, searching for meaning in a world that seemed content to ignore their existence. They were among doubtless thousands, if not tens of thousands, of young men and women who were among the first in their families—members of that first generation—to seek higher education. Their trek into such institutions was, in many ways, a voyage into a new and unfamiliar world. A trek that their earlier, unchallenging education left many youth woefully unprepared for.

What made these two emerge as remarkable men was not so much that they possessed remarkable qualities, as that this was a truly remarkable time.

It was the mid 1960s, movements were circling the globe like fresh winds blowing through stale, unopened, darkened rooms. Wafting on those winds were the seductive scents of rebellion, resistance, and world revolution!

In West Oakland, California, where Merritt College was then located, the biggest issue sparking discussion was the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Although it seemed that the immediate problem of a nuclear war between the US and the USSR over Cuba had been averted, the terror of possible atomic war was as real as moonlight. The international tensions of the times caused the era’s students to question the world they were growing into. And, if that were not enough, the rising Civil Rights movement in the US South brought domestic questions to the debate amongst the young.

A student named Bobby Seale walked the campus, observing and listening to those who possessed the power to engage in verbal combat and hold court. Speakers didn’t just spout their opinions to silent observers, but engaged in debate, parrying a variety of rapid-fire questions from the massed throng. One speaker—a young guy named Huey—spoke with such militant conviction and knowledge that Bobby stood transfixed:

I guess I had the idea that I was supposed to ask questions in college, so I walked over to Huey and asked the brother, weren’t all these civil rights laws the NAACP was trying to get for us doing some good? And he shot me down too, just like he shot a whole lot of other people down. He said, it’s all a waste of money, black people don’t have anything in this country that is for them. He went on to say that the laws already on the books weren’t even serving them in the first place, and what’s the use of making more laws when what we needed was to enforce the present laws?1

This thriving, questioning atmosphere gave way to broader challenges. Huey had joined the school’s Afro-American Association to try to formulate answers to the questions that hung in the air. Bobby was soon to follow:

That’s the kind of atmosphere I met Huey in. And all the conflicts of this meeting, all the blowing that was going on in the streets that day during the Cuban crisis, all of that was involved with his association with the Afro-American Association. A lot of arguments came down. A lot of people were discussing with three or four cats in the Afro-American Association, which was developing the first black nationalist philosophy on the West Coast. They got me caught up. They made me feel that I had to help out, be a part and do something. One or two days later I went around looking for Huey at this school, and I went to the library. I found Huey in the library, and I asked him where the meetings were. He gave me an address card and told me there were book discussions.2

How does such a benign meeting presage the emergence of the Black Panther Party? What these recollections reveal are the various strands of thought that were circulating through the Black student and radical community at the time, and would later coalesce and congeal as the beginnings of ideology. The two men seemed to be searching for something—perhaps answers to why the world was as jumbled up as it seemed, perhaps for a way out of their daily grind, perhaps for that which Black Americans had searched for centuries—for freedom.

They were looking for an organization that would represent their collective voice. Even at this early stage, there existed positions that would later re-emerge espoused and reflected by the Black Panther Party: a questioning of the status quo; a sense of alienation not only from the US government, but, reflecting a class divide, also from the elite of the Civil Rights movement; and the germ of recognizing the importance of the international arena to the lives and destinies of Blacks in America.

Their first interaction also suggests the beginnings of the power relations that would last for the duration of the existence of the Black Panther Party. It is clear that, although younger, Huey P. Newton possessed a mind far more active, far more flexible, and far more wide-ranging than did Bobby Seale. Newton emerged as the teacher, though Seale too was pivotal.

Seale would introduce Newton to the Caribbean-born Algerian revolutionary Frantz Fanon through his masterpiece, The Wretched of the Earth. A notoriously slow reader, Newton would read the extraordinary book six times.3 For Newton, and for many other Black Americans, Fanon’s words were a revelation, not merely of African colonial conditions, but of the world’s problems and why Black America was in such a wretched state:

The mass of the people struggle against the same poverty, flounder about making the same gestures and with their shrunken bellies outline what has been called the geography of hunger. It is an under-developed world, a world inhuman in its poverty; but also it is a world without engineers and without administrators. Confronting this world, the European nations sprawl, ostentatiously opulent. This European opulence is literally scandalous, for it has been founded on slavery, it has been nourished with the blood of slaves and it comes directly from the soil and the subsoil of that under-developed world. The well-being and the progress of Europe have been built up with the sweat and the dead bodies of Negroes, Arabs, Indians and the yellow races.4

For one seeking to make sense of the vast, bleak panorama of poverty in the American ghetto, as contrasted with the projected stately order and opulence of white wealth, Fanon’s brave and passionate prose held powerful illumination. Black folks in America saw themselves in the villages of resistance and saw their ghettos as little more than internal colonies similar to those discussed in Fanon’s analysis.

Fanon’s anticolonial and anti-imperialist perspective was not the only influence on the young Newton. The Black nationalist Malcolm X had a powerful impact upon him, one he termed “intangible” and “deeply spiritual.”5 Newton regularly visited Muslim mosques in the Bay Area and discussed the problems facing Black Americans with members of the Nation of Islam (NOI). He heard Malcolm X, accompanied by a young convert then named Cassius Clay, speak at Oakland’s McClymond High School and found the intense young minister an impressive man “with his logic” and his “disciplined” mind.6 He seriously considered joining the NOI, but growing up as a preacher’s kid

I could not deal with their religion. By this time, I had had enough of religion and could not bring myself to adopt another one. I needed a more concrete understanding of social conditions. References to God or Allah did not satisfy my stubborn questioning.7

Fanon’s analysis mixed well with Malcolm’s militant anti-establishment oratory. Malcolm spoke often about the anticolonial liberation movements in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. He spoke also of the Bandung Conference (1955) in Indonesia where African and Asian nations pledged support to the anticolonial movement. Malcolm X and Fanon were deep influences on Newton and played a role in moving him to develop an anti-imperialist and radical perspective:

From all of these things—the books, Malcolm’s writings and spirit, our analysis of the local situation—the idea of an organization was forming. One day, quite suddenly, almost by chance, we found a name. I had read a pamphlet about voter registration in Mississippi, how the people in the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, had a black panther for its symbol. A few days later, while Bobby and I were rapping, I suggested that we use the panther as our symbol and call our political vehicle the Black Panther Party.… The image seemed appropriate, and Bobby agreed without discussion. At this point, we knew it was time to stop talking and begin organizing.8

Black and Third World freedom struggles, nationally and internationally, deeply influenced the two men that formed the Black Panther Party. Several books in addition to Fanon’s were pivotal to this process.

While Robert Williams’s 1962 Negroes With Guns, as well as the works of V.I. Lenin, W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, Dostoyevski, Camus, and Nietzsche fed the growing intellect of Newton, young people of that era were being fed soul food—cooked on the burning embers of Watts, the ghetto rebellion that raged the year before. The books of Black revolutionaries and other thinkers were deeply influential, but what to do?

In his twenty-fourth year of life, Newton would organize a group that would spread across the nation like wildfire. The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPPFSD), founded on October 15, 1966, and later renamed the Black Panther Party (BPP), would gain adherents in over forty US cities, with subsidiary information centers (called National Fronts Against Fascism offices) across the nation.

The Black Panther Party was born.

Southern Roots

If one examined the places of origin of leading members of the organization, despite its founding in northern California, one could not but be struck by the number of people who hailed from the South. The first two Panthers, Newton and Seale, were native to Louisiana and Texas, respectively. The BPP’s Minister of Information, Eldridge Cleaver, was born in Arkansas and the Los Angeles chapter’s Deputy Minister of Defense, Geronimo ji-Jaga (né Pratt), was also born in Louisiana. The Party’s Chief of Staff, David Hilliard, and his brother, Roosevelt “June” Hilliard, were country boys from Rockville, Alabama. BPP Communications Secretary, and one of the first women to sit on the Central Committee, Kathleen Neal Cleaver, was born into an upwardly mobile Black family in Texas.9 Elbert “Big Man” Howard, an editor of The Black Panther newspaper for a time, was a native of Chattanooga, Tennessee.

It seems the young folks who established and staffed the organization came from predominantly southern backgrounds and therefore had to have suffered a kind of dual alienation. First, the global, overarching feeling of apartness stemming from being Black in a predominantly white and hostile environment. Second, the distinction of being perceived as “country,” or “southern,” a connotation that has come to mean stupid, uncultured, and hickish in much of the northern mind.

They were born into families that brought up the rear of the Great Migration, that vast trek of Black folks fleeing the racial terrorism, lack of opportunity, and stringent mores of social apartheid of the US South. Although they arrived in California as youths and adolescents, they never truly felt at home there, looking to the bayous, deltas, fields, and farmlands of their birthplaces almost as ancestral homes. This was perhaps best voiced by David Hilliard:

Yet Rockville remains a profound influence on my life.… “We’re going back to the old country,” my cousin Bojack used to say when we were growing up and preparing for a trip south. Rockville remains the closest I can get to my origins, to being African.10

For millions of African Americans living in the North, the same can be said. This almost rural mindset would have repercussions for the Party as it grew and expanded into northern cities with teeming Black ghettos.

Roots of Black Radicalism

For decades, neither scholars nor historians bothered to address the existence of the Black Panther Party. If the BPP was a member of the family of Black struggle and resistance, it was an unwelcome member, sort of like a stepchild.

The accolades and bouquets of late twentieth-century Black struggle were awarded to veterans of the civil rights struggle epitomized by the martyred Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Elevated by white and Black elites to the heights of social acceptance, Dr. King’s message of Christian forbearance and his turn-the-other-cheek doctrine were calming to the white psyche. To Americans bred for comfort, Dr. King was, above all, safe.

The Black Panther Party was the antithesis of Dr. King.

The Party was not a civil rights group. It did not believe in turning the other cheek. It was markedly secular. It did not preach nonviolence, but practiced the human right of self-defense. It was socialist in orientation and advocated the establishment (after a national plebiscite or vote) of a separate, revolutionary, socialistic, Black nation-state.

The Black Panther Party made (white) Americans feel many things, but safe wasn’t one of them.

For late twentieth-century scholars and historians trained to study safe history, the Black Panthers represented a kind of anomaly, rather than a historical descendant of a long, impressive line of Black resistance fighters.

In fact, the history of Africans in the Americas is one of deep resistance—of various attempts at independent Black governance, of self-defense, of armed rebellion, and indeed, of pitched battles for freedom. It is a history of resistance to the unrelenting nightmare of America’s Herrenvolk (master race) “democracy.”

For generations, Blacks have dreamed of a social reality that can only be termed national independence (or Black nationalism). They gave their energies and their strength to find a place where life could be lived free.

The Black Panthers represented the living line of their radical antecedents. In the dichotomy popularized in a speech by Malcolm X, the Black Panthers represented the “field slaves” of the American plantation who did not disguise their anger at the oppressive institution of bondage; Dr. King’s sweet embrace of all things American was typical of the “house slave” who—denounced by Malcolm—when the white slavemaster fell ill, asked, “Wassa matter, boss? We sick?”

“The field slaves,” Malcolm preached bitingly, “prayed that he died.”

The origins of that resistance may be dated (on the North American landscape) to 1526, when Spaniards maneuvered a boatload of captive, chained Africans up a river (in a land now called South Carolina) and nearly one hundred captives broke free, slew several of their captors, and fled into the dense, virgin forests to dwell among the aboriginal peoples there in a kind of freedom that their kindred would not know for the next 400 years.11 Over that period of time, there would be several attempts to establish a separate Black polity away from the US mainland, situated in Africa, in Haiti, in Central America, or in Canada. With the exception of the struggling Republic of Liberia, established on Africa’s West Coast in 1822 by US Black freedmen and -women under the aegis of the American colonization societies, none of the other projects offered a viable site for establishing a separate African American polity.

Even the Republic of Liberia had its critics. Indeed, Liberia was considered a mockery by nineteenth century Black nationalist Dr. Martin Delany. Traveling the world in search of an independent “Africo-American” nation-state, he left little doubt that Liberia was not the answer, calling it “a burlesque of a government—a pitiful dependency on the American Colonizationists, the Colonization Board at Washington city, in the District of Columbia, being the Executive and Government, and the principal man, called President, in Liberia, being the echo…”12

The inborn instinct for national Black independence found various forms of expression: For example, in 1807, in Bullock County, Alabama, Blacks organized their own “negro government” with a code of laws, a sheriff, and courts. Their leader, a former slave named George Shorter, was imprisoned by the US Army.13 As early as 1787, a group of “free Africans” petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for leave to resettle in Africa, because of the “disagreeable and disadvantageous circumstances” under which “free Africans” lived in post-Revolutionary America.14 The petitioning delegation was led by Black Masonic leader, Prince Hall, who exclaimed:

This and other considerations which we need not here particularly mention induce us to return to Africa, our native country, which warm climate is more natural and agreeable to us, and for which the God of Nature has formed us, and where we shall live among our equals and be more comfortable and happy, than we can be in our present situation and at the same time, may have a prospect of usefulness to our brethren there.15

Here may be found one of the earliest manifestations of a back-to-Africa movement, expressed nearly 120 years before the heralded Black nationalist Marcus Garvey. It was a deep expression of alienation with American life, even in Massachusetts where Africans had perhaps the best and most free life in the colonies.

It would be disingenuous to suggest that only Blacks sought the establishment of a separate Black nation-state. Some of the deepest thinkers in American life expressed surprisingly similar thoughts to the Black Masonic leader.

Six years before Prince Hall’s petition was submitted in Boston, one of the brightest minds of the Old Dominion was writing that there were “political,” “physical,” and “moral” objections to Blacks living in political equality with whites in the same polity. In the year he resigned from the office of Governor of Virginia, and several decades before he would occupy the office of president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson wrote:

It will probably be asked, why not retain and incorporate the blacks into the state, and thus save the expense of supplying, by importation of white settlers, the vacancies they will leave? Deep-rooted prejudices entertained by the whites, ten thousand recollections by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained, new provocations; the new distinctions which nature has made, and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce compulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of one or the other race.16

What may surprise many is that another major American political thinker, Abraham Lincoln, while a sitting president, expressed quite similar views over three-quarters of a century later. In an 1862 address to a “Colored Deputation” in Washington, DC, the president expressed his thinking on Black colonization:

Why should they leave this country? This is, perhaps, the first question for proper consideration. You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any two races. Whether it is right or wrong I need not discuss, but this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think your race suffer very greatly, many of them by living among us, while ours suffer from your presence. In a word we suffer on each side. If this be admitted, it affords a reason at least why we should be separated.17

Lincoln proposed mass resettlement of US Blacks to lands in Central America.18 What is remarkable is that Lincoln’s vision, pronounced while the country was convulsed in the throes of civil war, shares so much with the Black separatism best typified by the former, formal position of the Nation of Islam. While the NOI’s position is termed radical, racist, and hateful, Lincoln is lionized as the Great Emancipator. Not surprisingly, the “Colored Deputation” received the Lincoln resettlement proposal coldly.19

After the war ended with Union victory, a Republican Reconstruction-era governor of Tennessee, William G. Brownlow, would urge the US Congress to set aside a separate US territory for Black settlement. His 1865 proposal would establish a “nation of freedmen.”20 Historian Eric Foner has found in periods of heightened Black conflict with, and political disenfranchisement by, the white majority and its political elites, the hunger for African independence, or nationalism, is rekindled, and re-emerges in Black popular demands:

One index of the narrowed possibilities for change was the revival of interest, all but moribund during Reconstruction, in emigration to Africa or the West. The spate of black public meetings and letters to the American Colonization Society favoring emigration in the immediate aftermath of Reconstruction reflected less an upsurge of nationalist consciousness than the collapse of hopes invested in Reconstruction and the arousal of deep fears for the future by the restoration of white supremacy. Henry Adams, the former soldier and Louisiana political organizer, claimed in 1877 to have enrolled the names of over 60,000 “hard laboring people” eager to leave the South. “This is a horrible part of the country,” he wrote the Colonization Society from Shreveport, “And our race can not get money for our labor.… It is impossible for us to live with these slaveholders of the South and enjoy the right as they enjoy it.”21

Nationalism, therefore, was a live option that had considerable support in both the Black and white communities, that waxed and waned according to the political, economic, and psychosocial context of life for Black folks in white America.

While periods of tension and strife gave rise to nationalist aspirations, for some the struggle for survival demanded that people take immediate, militant, and indeed violent action to protect their lives and their freedom. Nationalism may have been a considered aspiration; survival was sheer necessity. People thrown into an untenable situation had to find remarkable ways of getting out. Those qualities and impulses lie deep within the psyches and historical experiences of Black people in the Americas—people who have been far more radical than a tame, sweet, civil rights–oriented history might suggest.

Black Roots of Resistance

When one speaks of African Americans, it is clear to many of whom we speak. What may be unclear, however, is how the very term itself masks deep ambiguities within Black and white consciousness. It is but the latest nominally socially accepted term for a people who long predate the United States.

Among all the myriad people who call themselves Americans, the sons and daughters of Africa—called variously Africans, Negroes (and various pejorative derivations therefrom), gens de couleur, Africo-Americans, Afro-Americans, colored people, Bilalians,22 African Americans, and the recently revived people of color—view their nationality ambiguously, as if more a question than a self-evident certainty. That ambiguity is a natural result of the troubled history of Black people in the United States, who have tasted the bitter gall of betrayal by the nation of their birth, and, like the aboriginal peoples of the Americas, the so-called Indians (how long will we repeat the navigational errors of Columbus?), they have seen a long trail of broken promises.

Unlike most others who call themselves Americans, Africans did not immigrate here by choice, fleeing foreign princes in search of “freedom,” but were brought here in sheer terror, shackled, chained, and against their deepest will. This is therefore a home, not by the choice of one’s ancestors, but by a cruel kind of historical default.

The classic narrative of Olaudah Equiano, an eighteenth-century captive taken as a preteen boy from his Ibo clan in what would be modern-day Nigeria, reflects the terrors of millions of West Africans who were forcibly brought to the West in the holds of slave ships. His first sight of such a vessel (he, a boy of eleven years, had never seen a river, much less a coastal sea), and the strange, pale beings, filled him with dread. He felt like prey before ravenous beasts:

Their complexions too, differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke, which was very different from any I had ever heard, united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed, such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with the meanest slave in my own country. When I looked around the ship too, and saw a large furnace of copper boiling and a multitude of black people of every description, chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow I no longer doubted of my fate; and quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck, and fainted.23

Equiano thought these strange, red-faced beings were bad spirits who would surely kill and then eat him and the other sad-faced Black people. He used his wits and business acumen to survive a brutal bondage in Georgia, and, sold to a sea captain, lived on board slaving vessels, learned the craft of seamen, and traveled the world, eventually buying his freedom and settling in London.

His horrific memories of the torture, brutalities, and savageries of the slave trade stand like dark sentinels in the recesses of Black consciousness of what it means to be Black in America. Almost every African American knows that his or her ancestor entered the doorway to America through the stinking hold of a vessel such as that which transported Equiano.

These beginnings, so radically different from most other Americans, may be the psychic wellspring of so much that is radical in contemporary Black America. What white America perceived as radical may have been the norm in the very different context of Black life in the midst of a white supremacist, hostile, and patriarchal society. In a state where the violently enforced norm was white supremacy and Black devaluation, it should surprise no one that there was resistance, nor that this would stimulate a radical social response.

Much of African American history, then, is rooted in this radical understanding that America is not the land of liberty, but a place of the absence of freedom, a realm of repression and insecurity. Only such a people as this could create the haunting hymns of the spirituals, in which people sang so movingly of loss and yearning:

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,

a loooong way from hooome,

a long way from home!

Some Africans, early in the eighteenth century, resisted the status quo by seizing control of their slaveships and setting sail for freedom back in Africa. Ninety-six Africans aboard the Little George slipped their bonds and overpowered the crew. Some of the crew were not slain, but were locked in their cabins so that they could not interfere with the trek home. The Black naval rebels sailed for nine days and made landfall on the West African coast in 1730.

Two years later, the captain of the William was slain by its Black captives, its crew was set adrift in the waters of the Atlantic, and a new, rebel crew pointed the bow of the vessel homeward, to Africa.24

Nor were things quiet and sedate for Africans on land.

The period of the 1730s and 1740s has been seen by some historians as an era of incessant resistance. One contemporary observer described the period, almost as if he were referring to a prevalent disease, as “the contagion of rebellion” sweeping the colonies. Indeed, this spirit of rebellion flashed up and down the coasts of the British colonies and encircled the isles claimed by tribes of Europe in the West Indies, lighting fires of freedom in the dark night of bondage.

During the 1730s and early 1740s, the “Spirit of Liberty” erupted again and again, in almost all of the slave societies of the Americas, especially where Coramantee slaves were concentrated. Major conspiracies unfolded in Virginia, South Carolina, Bermuda, and Louisiana (New Orleans) in the year 1730 alone.25

Historians cite a remarkable man named Samba, who featured predominantly in the 1730 New Orleans revolt. He had previously led an unsuccessful rebellion against a French slave-trading fort back in Africa and had mutinied while aboard a slave vessel. The town fathers in New Orleans responded to his incessant quest for liberty by giving him a brutal, tortuous death. This state terror did not diminish the thirst for liberty surging in Black hearts in New Orleans. Captives there organized an uprising just two years after Samba’s sacrifice.

Historians describe a coherent cycle of rebellion that threw the Atlantic into convulsions of resistance to the established colonial slavocracies:

The following year witnessed rebellions in South Carolina, Jamaica, St. John (Danish Virgin Islands), and Dutch Guyana. In 1734 came plots and actions in the Bahama Islands, St. Kitts, South Carolina again, and New Jersey. The latter two inspired by the rising in St. John. In 1735–36 a vast slave conspiracy was uncovered in Antigua, and other rebellions soon followed on the smaller islands of St. Bartholomew, St. Martin’s, Anguilla, and Guadeloupe. In 1737 and again in 1738, Charleston experienced new upheavals. In the spring of 1738, meanwhile, “several slaves broke out of a jail in Prince George’s County, Maryland, united themselves with a group of outlying [or escaped] Negroes and proceeded to wage a small-scale guerrilla war.” The following year, a considerable number of slaves plotted to raid a storehouse of arms and munitions in Annapolis, Maryland, to “destroy his Majesty’s Subjects within this Province, and to possess themselves of the whole country.” Failing that, they planned “to settle back in the Woods.” Later in 1739, the Stono Rebellion convulsed South Carolina. Here the slaves burned houses as they fought their way toward freedom in Spanish Florida. Yet another rebellion broke out in Charleston in June 1740, involving 150 to 200 slaves, fifty of whom were hanged for their daring.26

In a study of the radical underpinnings of Black thought it is not sufficient to provide a kind of caramel-colored, sepia-toned version of US history. Consider that these rebellions occurred but a few decades before the Declaration of Independence and the subsequent American Revolution. In those battles for liberty it is perhaps unremarkable to note that some 5,000 Blacks were eventually integrated into the Army of the Continental Congress, although General George Washington, a slaveholder from Virginia, initially opposed their enlistment. The First Rhode Island Regiment, an elite regiment of Black enlisted men and white officers, carried the day against the British at Yorktown, playing a pivotal role in forcing the surrender of Cornwallis.27

What is less well known is that well over ten times that number, some 65,000 Africans, joined the British cause. They joined not because of any craven loyalty to the Crown, nor any disloyalty to the colonies, but rather because of the age-old impetus of self-interest. Britain’s Lord Dunmore offered freedom to all “negroes” who would fight for the Crown, and tens of thousands leapt at the opportunity. Dunmore organized a corps of Black former slaves into the Ethiopia Regiment, who wore the motto “Liberty to Slaves” on their tunics. This regiment helped the British capture and torch Norfolk, Virginia, on New Year’s Day, 1776.

When the British were forced to withdraw in 1783, over 20,000 Africans fled the United States. Having fought for the losing side of the Revolution, they had no desire to remain in the slavocratic states. They may have lost the war, but they did not lose all. Many lived lives of freedom that their former countrymen would not experience for almost a century, settling in London, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and other British dominions.28

Seen from this perspective, did they really lose?

This is not to suggest that the British were, as a rule, liberators of African slaves. They were not.

Lord Dunmore was putting forth a war policy to the benefit of the Empire; if, in support of that objective, strategy dictated the freedom of a few thousand Africans, all to the good. The Irish-born British parliamentarian Edmund Burke, who promoted conciliation with the Americans, saw the Dunmore proposal as sheer hypocrisy. Burke asked whether Blacks should accept “an offer of freedom from that very nation which has sold them to their present masters?”29

Indeed, just over a decade before Dunmore’s offer, Blacks living in the Spanish colony of Florida, and especially those hundreds of Maroons who lived in Fort Mosa, just north of St. Augustine, set sail for Cuba rather than live under the British Crown. Fort Mosa and the surrounding Black community it defended constituted one of the earliest Black settlements on the land that we now call the United States. Fort Mosa was the name that Black fugitives, Seminole Indians, and Floridian Spanish used. The English-speaking people of Georgia and South Carolina called the site Negro Fort and viewed it as a threat to the slave system. When the British took over Florida in 1763, the Maroons fled with the Spanish.30

For Africans, whether in Virginia or Spanish Florida, the central objective remained the same: which way freedom? If the price for freedom was to ally with the British against the slavery-addicted Americans, or to turn from Spain for liberty and dignity among aboriginal peoples like the Seminoles, so be it.

Freedom was ever the goal.

Resistance After the “Revolution”

After what some historians have termed the Baron’s Revolt of the nouveau riche Americans against the established, wealthy, and rapacious Crown of England for “freedom,” there were millions of Blacks in the newly independent American states who knew that freedom was still not theirs. They were slaves before the “buckra war”31 for freedom and independence and were still in bondage after it ended.32

The post-Revolutionary era brought the language of liberty out into the open, if not into reality. It also brought with it a methodology.

People must fight for their freedom.

On the Revolution’s eve, whites of property, who cried loudest for “liberty” from British tyranny, strove mightily to tighten the shackles on the people they held in unremitting bondage. As radical historian Herbert Aptheker has noted:

A letter written July 31, 1776, by Henry Wynkoop, a resident of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to the local Committee of Safety requested the dispatching of ammunition in order to quiet “the people in my neighborhood [who] have been somewhat alarmed with fears about negroes and disaffected people injuring their families when they are in the service.”33

The Revolution was scarcely a decade past when the following letter, posted some months earlier from Newbern, North Carolina, appeared in the Boston Gazette of September 3, 1792:

The negroes in this town and neighborhood, have stirred a rumour of their having in contemplation to rise against their masters and to procure themselves their liberty; The inhabitants have been alarmed and keep a strict watch to prevent their procuring arms; should it become serious, which I don’t think, the worst that could befal [sic] us, would be their setting the town on fire. It is very absurd of the blacks, to suppose they could accomplish their views, and from the precautions that were taken to guard against surprise, little danger is to be apprehended.34

Put quite another way, the southern correspondent suggests to the northern journal, in essence, “it is absurd for these negroes to think that the Revolution was about anything other than white liberty!”

It was, in fact, a Baron’s Revolt, a revolution fought for the “liberty” of deciding who would hold Africans in bondage—Americans or the British? Who would reap the wealth from their forced labor? Who would receive the fruits of this stolen land that African labor produced?

Liberty, indeed!

It was during this post-Revolutionary era that the African people of the Americas launched massive armed rebellions that echo down the corridors of time for their sheer boldness in attempt and execution of their will to be once and forever free. Two centuries after their heroic bids for freedom, the leaders of these rebellions are still regarded with a strange American ambivalence that revolves around the crucible of race. To many whites they are seen as madmen; to some Blacks they are remembered as armed prophets of freedom. Gabriel Prosser (d. 1800), Charles Deslondes (d. 1811), Denmark Vesey (d. 1822), Nat Turner (d. 1831), and “Cinque” Singbeh Pi’eh (d.1839), of the mutiny aboard the Spanish schooner La Amistad, dwell in the hearts, minds, and souls of millions of contemporary African Americans, as people who fought against desperate odds, against a ruthless enemy, for a breath of freedom. Their names still live in millions of Black mouths, in stories told from generation to generation, almost two centuries after their passing.

Emblematic of this stellar and bloody period of armed Black resistance, one of that number who will exemplify how deeply this radical example has permeated Black spiritual consciousness, is Gabriel Prosser.

Deeply inspired by the biblical tale of Samson, Gabriel came to believe he had been appointed by the Lord to become the deliverer of his people. A young man of impressive physical and mental gifts, he shared his inner convictions with other captives. He interpreted the verses of the Bible with them, explaining that the tales told referred to the living present—summer 1800—and predicted the deliverance of the people from a hellish bondage. He preached this verse to his fellow captives:

And when he came unto Lehi, the Philistines shouted against him; and the Spirit of the Lord came mightily upon him, and the cords that were upon his arms became as flax that were burnt with fire, and his bands loosed from off his hands. And he found a new jawbone of an ass, and slew a thousand men therewith.… And he judged Israel in the days of the Philistines for twenty years.35

The cords and bands of this passage mean the bondage of slavery, Gabriel explained. And the Philistines? They were the slavemasters, of course. Gabriel and his fellow captives were to steal or make weapons—the jawbones of an ass—and they would judge the Philistines and erect a Black kingdom—there, near Richmond—and live life in liberty.36

His inspiring manner and his masterful interpretation of the Bible drew people to join him in this great task. Before long, he was joined by his wife, Nanny, and his brothers, Martin and Solomon. As the movement spread, 1,000 rebels joined his force.

Gabriel conducted reconnaissance in Richmond to acquaint himself with armament stores and the lay of the land. As weapons and bullets were forged, the night to strike was selected. All was in readiness.

On the afternoon of the rising, two slaves, Tom and Pharoah, broke news of the plot to their master, who promptly informed the governor (and later president), James Monroe. Monroe quickly mobilized 650 men and placed state militia commanders on alert.37

The early evening march on Richmond by Gabriel’s 1,000- strong force got mired, literally, as rains made the roads impassable. With travel so obstructed, they decided to disperse, not knowing that the rebellion had already been betrayed. An army of bondsmen and bondswomen, wielding farm implements, a few guns, and the inspiration of their “Black Samson,” melted into the steamy August night, to await a new signal, having come within six miles of Richmond.

The second signal would never come. Over the next few days, a number of rebels, including their charismatic leader, Gabriel Prosser, were caught in the net. None could be compelled to confess or provide information on the plan. Monroe met Prosser, and the governor would later note: “From what he said to me, he seemed to have made up his mind to die, and to have resolved to say but little on the subject of the conspiracy.”38

At least thirty-five rebels, including Gabriel, were hanged.

Like his compatriots in the Grand Conspiracy of Rebellion against bondage, Gabriel did not die to millions of his fellow captives. They still live on, in blessed memory, in spirituals, in legend, in tales in the night, and in the spirit of resistance of an oppressed people.

Armed Self-Defense

We must add to the great and well-known names of revered historical figures the long and impressive history of hundreds, indeed thousands, of largely anonymous Africans who fought, sometimes armed, against the forces of white nationalism and white supremacist terrorism.

The 1763 flight of the Maroons and the abandonment of Fort Mosa did not end the use of the site. Half a century later hundreds of Africans fought a pitched battle against the Americans from the well-armed garrison, now known by all as Negro Fort. Blacks (and their “Indian” relatives) had good reason to live in an armed, well-defended fort along the banks of Florida’s Apalachicola River, and it wasn’t for the same reason that whites, who lived further to the west, would later live in or near forts.

The white fort-dwellers feared attacks from “Indians” who opposed encroachments upon their tribal lands.

The Black fort-dwellers feared attacks from whites (or Native Americans hired by them) who wanted to place them back in slavery.

Andrew Jackson as a Major General of the US Army, not yet president, left no doubt such a fear was justified by his communique to a Spanish governmental official in Pensacola, Florida, dated April 23, 1816:

A Negro Fort erected during our late war with Britain … [here, Jackson refers to the War of 1812, not the Revolution] has been strengthened since the period and is now occupied by upwards of two hundred and fifty Negroes, many of whom have been enticed away from the service of their masters—citizens of the United States: all of whom are well clothed and disciplined.…39

Jackson, who would emerge in his military and political careers as the worst enemy the Native people ever encountered, threatened the Spanish commandant, telling him the fort would be “destroyed” if Spain failed to “control” its residents.40

Herbert Aptheker calculated Negro Fort’s inhabitants at roughly 300 people (Black men, women, and children), with “some thirty Indian allies.” He recounts a ten-day siege of the facility by US forces, which concluded when American cannon fire struck the fort’s armory stores and exploded, killing some 270 of its inhabitants.41

Many Americans are generally familiar with the long history of US-“Indian” warfare, but how many know that the hardest fought battles were the three US-Seminole Wars? Or that these Black, white, and red wars were regarded as essentially wars fought for Black liberation? So many Africans fought on the side of the Seminoles that US General Thomas Jesup would write: “This, you may be assured, is a negro, not an Indian war.”42

This war was fought to re-enslave Blacks who lived in “Indian” territories and because whites feared red-Black unity. It was also fueled by the ever-present white hunger for “Indian” lands.

White American contempt for Native land possession is evinced by their rapacious craving for it, wherever it existed, and their determination, by whatever means possible, to acquire it. As an attorney, John Quincy Adams, arguing in the US Supreme Court, put the case for white seizure of Native lands in stark terms:

What is the Indian title? It is mere occupancy for the purpose of hunting. It is like our tenures; they have no idea of a title to the soil itself. It is overrun by them, rather than inhabited. It is not a true legal possession.43

In the Court’s Fletcher v. Peck case, Adams’s view was made into the law of the land, essentially legalizing seizure and land-theft, because Native Americans had a different cultural, legal, and spiritual relationship to the land. They didn’t use paper and alphabetic formats to record their important events; they used skins or bark and pictographs to communicate ideas. They didn’t inhabit land, they “overran” it.

Adams’s argument of 1802 marked the legal justification for American lebensraum and expansion into “Indian” territories.

What really incensed whites, however, was the spectacle of Africans living in their own villages as nominally free people, or Africans living in maroonage as part of the Seminole tribes. To Africans who escaped from a bitter bondage in neighboring Georgia, or North Carolina, life among the “Indians” in Seminole villages in Florida must have seemed a whole lot like freedom. For, even if bought or captured by a Seminole, a captive had standing that more resembled the institution of captivity in Africa than in the Americas. One’s children were born free, regardless of the condition of the parent.

Moreover, many Africans lived in perfect freedom among the Seminoles, serving as interpreters and warriors. Some even became chiefs. It was this very issue, Black freedom, that led to the breakaway and formation of the Seminoles from the Creek nation. The 1796 Treaty of Colerain contained a pledge from headmen of the Creeks to return Black fugitives to owners in the United States. This pledge excluded the Lower Creeks who lived north of the Florida border and the Seminoles who lived south of it, who never felt themselves bound by the pact. This marked a permanent divide between them and their relatives to the north.44

Historians like J. Leitch Wright, Jr., utilize the term Muscogulges as a name for the people of this region, in part for the prominent usage of the Muskogee language. He notes that Creek is an English term applied to people living amidst the riparian regions of the Southeast. Similarly, the term Seminole is a Spanish appellation that has its roots in the term cimarron, an Americo-Spanish term for runaway.45

Wright reports that “Black Indians” played a pivotal role in establishing Muscogulge, or Seminole, territory as sites of resistance to white expansion and centers of Black freedom:

Blacks constituted an important component of the Muscogulges, especially of those living in Florida. For years [US soldiers and Generals] McIntosh and Jackson had persecuted them, destroying the Negro Fort, Miccosukee, and Bowlegs Town and sending off prisoners in strings to Georgia and Alabama. Even so, many had escaped and during the 1820s lived in swamps, hummocks, and islands in the vicinity of Tampa Bay. Seminole agent Gad Humphreys recaptured the fugitive Negro John, who belonged to a Saint Augustine widow, chained him first about the neck, and subsequently ordered the blacksmith to put on handcuffs and leg irons. But John escaped again … and again … and again, in each instance apparently aided by a black Seminole. Slave and free Negroes resided in Indian villages scattered throughout Florida, on Indian plantations on the Apalachicola River, and with whites in Saint Augustine and Pensacola, and they were variously known as Negroes, Negro-Indians, and Indians. A continuous and easy intercourse existed between black Muscogulges in Indian settlements and Negroes serving in Florida, Alabama, and Georgia on white plantations, as field hands or in Saint Augustine and other cities as domestics, artisans, and fishermen.46

Three wars and a number of smaller battles demonstrate a practice of armed resistance. The Seminole Wars were as much Black wars for freedom as they were Indian wars against white expansion into their lands and against their removal to reservations.

John Brown’s Army

No tale of a radical people would be complete absent mention of the raid on Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, by John Brown and his small yet intrepid cadre of Black and white freedom fighters. Although presented in traditional US history as the act of a madman, little noted is the fact that Brown had, among his property when captured, a newly written Constitution and Declaration of Independence.

The documents were drawn up by Brown and a group of freedmen at the Chatham Convention, in Chatham, Ontario. Composed of forty-eight articles, the new constitution shared much in tone with the US Constitution, but it spoke out boldly and uncompromisingly on the evil of slavery. Here was none of the sweet evasion of political compromise. Drawn up by men who knew both the indignity of slavery as well as the license of liberty, the document’s preamble made overt their intention to abolish the “peculiar institution”:

Whereas slavery, throughout its entire existence in the United States, is none other than a most barbarous, unprovoked and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion—the only conditions of which are perpetual imprisonment and hopeless servitude or absolute extermination—in utter disregard and violation of those eternal and self-evident truths set forth in our Declaration of Independence.47

The Declaration was a naked rebuke of the recent decision of the American Supreme Court in the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford case of 1857, which upheld slavery even in “free” states and stated, in part:

Therefore, we, citizens of the United States, and the oppressed people who, by a recent decision of the Supreme Court, are declared to have no rights which the white man is bound to respect, together with all other people degraded by the laws thereof, do, for the time being, ordain and establish ourselves the following provisional constitution and ordinance, the better to protect our persons, property, lives, and liberties, and to govern our actions.48

Brown and other sworn officers of the Chatham Convention did not fight for succession, but for a radical reformation of the American nation-state—one wholly and truly dedicated to freedom from human bondage.

During the 1859 siege of Harper’s Ferry, Brown and his men seized the armory in an attempt to foment a mass slave revolt and to initiate an armed retreat to a redoubt in the nearby Allegheny Mountains. From there they hoped a sustained harassment campaign could be conducted against the slavery system.

While it is obvious that the raid failed in its intended objectives, it is also true that the raid, the losses sustained, and the execution of Brown came to be seen as symbols of the antislavery, abolitionist ideal and as the first shots fired of the Civil War.

Of the seventeen rebels who were slain at Harper’s Ferry, nine were Black, several of whom had joined the action on the spot. One of the Blacks who survived the action and lived to tell the tale was Osbourne Anderson. While critical of his errors, Anderson lauded “Captain Brown” for his nobility, noting, “even the noble old man’s mistakes were productive of great good”:49

John Brown did not only capture and hold Harper’s Ferry for twenty hours, but he held the whole South. He captured President Buchanan and his Cabinet, convulsed the whole country … and dug the mine and laid the train that will eventually dissolve the union between Freedom and Slavery. The rebound reveals the truth. So let it be!50

Many a Union soldier would sing of John Brown’s body two years after his hanging, as they marched through the charred ruins of a Confederate stronghold during a bitter, wrenching war. Nearly 200,000 of the soldiers for the Union were Black men, some former slaves. Over 37,000 would die in the conflagration.

From Then ’til Now

At first blush, it appears that this discussion of radical, rebellious resistance to the American way of bondage takes place in the remote, distant past.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

The writer William Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.”51 Faulkner spoke of the durability of the myth of the (white) Lost Cause, an ennobled vision of the role of the South. It saw the Confederacy as principled defenders of state sovereignty and upholders of national honor against the northern invaders, carpetbaggers, and assorted scalawags.

If the past is not past to contemporary generations of white southerners, how can one presume that it is past for generations of African Americans, almost all of whom find their families little more than two generations removed from a bitter peonage in the southlands of American apartheid? For Black Americans, the unforgotten past is not a four-year war that is reflected in the ubiquitous monuments or the frequent flying of the Confederate battle flag (said to honor one’s heritage).

To Blacks cognizant of history, what remains unforgotten is the unending war that has lasted for five centuries, a war against Black life by the merchant princes of Europe. Unforgotten is the man-theft, the wrenching torture, the unremitting bondage—bondage that occurred for centuries to ensure that the Americans could sell cotton to the British, or that the British could sweeten their tea, or that the French could sweeten their cocoa, or that the Dutch could add great sums to their bank accounts.

This “past” is written in the many-hued faces in the average Black family, which may easily range from darkest ebony, to toffee, to café au lait, each a reflection of white rape of African women or of the tradition of concubinage exemplified by the New Orleans les gens de couleur libres. For many Blacks, the past is as present as one’s mirror.

It is in this sense that history lives in the minds of Black folk. In people who draw their inspiration from the rebellious, resistant, liberational examples of people like Nat Turner, Gabriel Prosser, “Cinque,” Harriet Tubman, Charles Deslondes, Denmark Vesey, and Sojourner Truth.

Contrary to what is generally supposed or socially projected in an era when the civil rights model holds sway, Blacks are far more militant, and far more angry, than their “leaders” suggest.

This was realized by Donald H. Matthews, an assistant minister of the African-American Methodist Church when he began to teach Bible classes in Oakland’s Taylor Memorial in the 1960s. As a Black clergyman, he attended a traditional seminary, where he studied the classic texts of contemporary Protestant thought, such as those set forth by Karl Barth (1886–1968) or Paul J. Tillich (1886–1965). Let us suppose that he diversified his scholarship with the relatively recent works of the late Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (1929–1968).

One so educated would be woefully unprepared to meaningfully address the myriad depths and scope of the social, spiritual, and psychological problems facing average African Americans. Matthews writes of the revelations that emerged when parishioners brought bitter memories and equally bitter experiences to bear as they shared their collective pain with the preacher:

I frankly never had realized the excruciating price that my elders had paid in carving out a place of dignity and humanity.

The women told their stories of having to wear dresses of extraordinarily modest length to deflect the “attentions” of white men. This solution, however, seldom was satisfactory, and girls often found themselves on northern-bound trains and buses to protect their sexual choice and bodily integrity.

The men spoke of resisting the efforts of land-owners who “suggested” that their wives should work alongside them in the backbreaking work of sharecropping with poor tools on poorer land. These acts of courage also tended to result in midnight train rides north, often just ahead of a lynch mob.…

I was startled to realize their political sensibilities were closer to Malcolm X than to Martin King and that they had Christian beliefs not to be found in Tillich’s or Barth’s systematic theologies. It was this combination of deep feeling, resistance, and African-based religious concepts that I could not find in my black theological texts, either. So I was left with their powerful and profound stories without a method of interpretation that did them justice.52

These women of Oakland, California, were poor, church-going, internal immigrants from the south. The last rivulets of the torrents that produced the great, black river that came to be called the Great Migration brought with them a searing rage that the soothing balm of Christian love and redemption could not quench. Matthews notes that his Wednesday night Bible class hailed mostly from Arkansas and Texas, with others from the Deep South, and so possessed the same history as the founders of the BPP.53

They spoke the deep, hidden truths of millions of women and men of their generation, of the loss of homeland that all who emigrate experience, of the anger attendant with such loss, and, undoubtedly, of the loss of hope when one learns that the new land, with its own brand of harassments, fears, insecurities, and transnational negrophobia, is not the heralded Promised Land.

That riotous, unresolved, roiling energy fed into the entity we came to call the Black Panther Party.

Armed resistance to slavery, repression, and the racist delusion of white supremacy runs deep in African American experience and history. When it emerged in the mid 1960s from the Black Panther Party and other nationalist or revolutionary organizations, it was perceived and popularly projected as aberrant. This could only be professed by those who know little about the long and protracted history of armed resistance by Africans and their truest allies. The Black Panther Party emerged from the deepest traditions of Africans in America—resistance to negative, negrophobic, dangerous threats to Black life, by any means necessary.