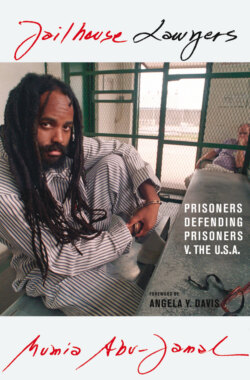

Читать книгу Jailhouse Lawyers - Mumia Abu-Jamal - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеBy Angela Y. Davis

One of the most important public intellectuals of our time, Mumia Abu-Jamal has spent more than twenty-five years behind bars, the majority of that time on death row. He is supported by millions all over the planet, not only because of the egregious repression he has suffered at the hands of the state of Pennsylvania, but because he has used his abundant talents as a thinker and writer to expand our knowledge of the hidden world of jails, prisons, and death houses in which he has spent the last decades of his life. As a transformative thinker, he has always taken care to emphasize the connections between incarcerated lives and lives that unfold in the putative arenas of freedom.

As Mumia has repeatedly pointed out, those of us who live in the “free world” are not unaffected by the system of state violence that relies on imprisonment and capital punishment as pivotal strategies for ordering society. While those behind bars suffer the most direct effects of this system, its raced, gendered, and sexualized modes of violence bolster the institutions and ideologies that inform our lives on the outside. In all of his previous books, Mumia has urged us to reflect on this dialectic of freedom and unfreedom. He has asked us to think deeply about the racial and class disproportions in the application of capital punishment, rarely taking advantage of the opportunity to call upon people to save his own life, but rather using his writing to speak for the more than three thousand people who inhabit the state and federal death rows. Over the years, I have been especially impressed by the way his ideas have helped to link critiques of the death penalty with broader challenges to the expanding prison-industrial-complex. He has been particularly helpful to those of us—activists and scholars alike—who seek to associate death penalty abolitionism with prison abolitionism.

In this book, Jailhouse Lawyers: Prisoners Defending Prisoners v. the U.S.A., Mumia Abu-Jamal introduces us to the valuable but exceedingly underappreciated contributions of prisoners who have learned how to use the law in defense of human rights. Jailhouse lawyers have challenged inhumane prison conditions, and even when they themselves have been unaware of this connection, they have implicitly followed the standards of such human rights instruments as the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (1955), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), and the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984). Mumia argues that the passage of the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA) is a violation of the Convention against Torture, for in ruling out psychological or mental injury as a basis through which to recover damages, such sexual coercion as that represented in the Abu Ghraib photographs, if perpetrated inside a U.S. prison, would not have constituted evidence for a lawsuit. If jailhouse lawyers are concerned with broader human rights issues, they also defend their fellow prisoners who face the wrath of the federal and state governments and the administrative apparatus of the prison. Mumia Abu-Jamal’s reach in this remarkable book is broadly historical and analytical on the one hand and intimate and specific on the other.

We are fortunate to be offered this history of jailhouse lawyers and this analysis of their legacies by one who can count himself among their ranks. Mumia’s words in the opening section of the book about the general conditions that create trajectories leading prisoners to jailhouse law are compelling. He writes of a “deep, abiding disenchantment with lawyers that forces some people to become their own, and also to assist others. In every penitentiary, in every state of the U.S., there are men and women who have learned, through study and experience, and trial and error, the principles of the law.”

Many of the jailhouse lawyers evoked in the pages of this book—including the author himself—were well educated before they entered prison. Studying the law was more a question of focusing their intellectual skills on a different object than of familiarizing themselves and becoming comfortable with the discipline of learning. But there are also those jailhouse lawyers who literally had to teach themselves to read and write before they set about learning the law. Mumia points to what was for me a startling revelation: jailhouse lawyers comprise the group most likely to be punished by the prison administration—more so than political prisoners, Black people, gang members, and gay prisoners. Whereas jailhouse lawyers are now punished by what Mumia calls “cover charges,” historically they could be charged with internal violations for no other reason than that they used the law to challenge prison guards, prison regimes, and prison conditions.

The passage of the Prison Litigation Reform Act (PLRA)—understood by many to have saved the court from frivolous lawsuits by prisoners—was a pointed attack on the jailhouse lawyers Mumia sets out to defend in these pages. He successfully argues that many significant reforms in the prison system resulted directly from the intervention of jailhouse lawyers. Some readers may remember the scandals surrounding conditions in the Texas prison system. But they will not have known that the first decisive challenges to those conditions came from jailhouse lawyers. Mumia refers, for example, to David Ruiz, whose 1971 handwritten civil rights complaint against Texas prison conditions was initially thrown away by the prison administrator charged with having it notarized. As we learn, Ruiz rewrote the complaint and bypassed the prison administration by giving it to a lawyer, who handed it over to a federal judge. This case, Ruiz v. Estelle, was eventually merged with seven other cases originating with prisoners. They challenged double- and triple-celling and work regimes that incorporated the violence of plantation slavery.

Moreover, Texas, along with other southern prison systems, relied on what were known as “building tenders,” i.e., armed prisoners acting as assistants to guards, for the governance of the institution. The largely white guards and building tenders poised against the majority Mexican-and African-American prisoners led to “abuse, corruption and officially sanctioned injustice.” For those who assume that charitable legal organizations in the “free world” were always responsible for the prison lawsuits that led to significant change, Mumia reminds us that what is now known as “prison law” was pioneered by prisoners themselves. These lawyers behind bars practiced at the risk of punishment and even death. Ruiz himself was placed in the hole after filing this lawsuit against the warden. But, as Mumia points out, the state of Texas was eventually compelled to disestablish the building tender system and to curtail its overcrowding and the overt violence of its regimes. Such contemporary suits as the recent one brought in part by the Prison Law Office against the state of California, which focuses on overcrowded conditions and the lack of health care in California prisons, have been precisely enabled by the work of jailhouse lawyers—those who risked violence and even death in order to make their voices heard.

In light of the major transformations that have historically resulted from the work of jailhouse lawyers, it is not surprising that Mumia argues strenuously against the Prison Litigation Reform Act, whose proponents largely relied on the notion that litigation by prisoners needed to be curtailed because of their proclivity to submit frivolous lawsuits. One of the cases most often evoked as justification for the passage of the PLRA was mischaracterized as claiming cruel and unusual punishment because the prisoners received creamy instead of chunky peanut butter. This was not the entire story, which Mumia offers us as a powerful refutation of the underlying logic of the PLRA. Popular representations of prisoners as intrinsically litigious were linked, he points out, to representations of poor people as more eager to receive welfare payments than they were to work. Thus he connects the 1996 passage of the PLRA under the Clinton administration to the disestablishment of the welfare system, locating both of these developments within the context of rising neoliberalism.

Mumia Abu-Jamal’s Jailhouse Lawyers is a persuasive refutation of the ideological underpinnings of the Prison Litigation Reform Act. The way he situates the PLRA historically—as an inheritance of the Black Codes, which were themselves descended from the slave codes—allows us to recognize the extent to which historical memories of slavery and racism are inscribed in the very structures of the prison system and have helped to produce the prison-industrial-complex. If slavery denied African and African-descended people the right to full legal personality and the practices of racialized second-tier citizenship institutionalized the inheritance of slavery, so in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, prisoners find that the curtailment of their capacity to seek redress through the legal system preserves and reaffirms that inheritance.

Mumia’s profiles include both men and women, both people of color and white people, with disparate motivations and often very different ways of identifying or not identifying themselves as jailhouse lawyers. Prisoners have challenged the law on its own terms in ways that recapitulate the grassroots organizing by ordinary people in the South that led eventually to the overturning of laws authorizing racial inferiority.

As Mumia points out, if there is increasing respect for the religious rights and practices of people behind bars, then it is largely due to the work of jailhouse lawyers. In the state of Pennsylvania, where Mumia himself is imprisoned, one extremely active jailhouse lawyer profiled in the book is Richard Mayberry, who initiated many important lawsuits, including the case known as I.C.U. (Imprisoned Citizens’ Union) v. Shapp, which broadly addressed health, overcrowding, and other conditions of confinement in Pennsylvania prisons.

The I.C.U. case ended in a settlement, which required an agreement by all parties. Mayberry served as class representative and signed on behalf of thousands of state prisoners, and a court-agreed settlement went into force, creating new rules that covered the entire state system. The I.C.U. provisions became the foundation for every subsequent regulation that governed the entire state, and they lasted for decades, until the passage of the Prison Litigation Reform Act. (161)

Mumia not only offers accounts of cases and profiles of prison litigators who have had a lasting impact on the prison system in the United States, he also reveals the extent to which jailhouse lawyers provide legal assistance to their peers, both with respect to their cases and with respect to institution violations. In relation to the latter, outside lawyers are often actually prohibited from representing prisoners, whereas jailhouse lawyers are permitted to assist prisoners in their defense of institutional charges.

Whether the lawsuits generated by jailhouse lawyers are expansive in their reach, potentially affecting the lives of large numbers of prisoners, or whether they are specifically focused on the case of a single individual, they have indeed made an enormous difference. Mumia Abu-Jamal has once more enlightened us, he has once more offered us new ways of thinking about law, democracy, and power. He allows us to reflect upon the fact that transformational possibilities often emerge where we least expect them.

Free Mumia!