Читать книгу Furnace - Muriel Gray, Muriel Gray - Страница 10

5

ОглавлениеThe cloud had lifted as she stood rigid and still on the grass. That was good. She watched the thin sunlight play amongst the bare branches of the ancient tree that stood solemnly in the wide street, and as her gaze moved down to the base of its massive bole, she frowned with irritation. There were suckered branches starting to form in clumps at the base. That meant only one thing. The tree was dying.

It must have been the men laying the cables last year. They had been told to make sure the trench came nowhere near the roots, to cut a path for the thick mass of plastic tubing and wire in between those delicate arteries of soft wood rather than through them. But they were like all workmen. Lazy. And this was the result.

She ground her teeth and concentrated on fighting the irritation.

Absence of malice, absence of compassion, absence of all petty human emotion. It was essential.

In a few hours she would let her thoughts return to the vandalized tree, but not now. The workmen would never be employed by her again. And that, she decided, would be the least of their worries.

But not now. Push the thought away and leave nothing. Nothing at all.

Quarter of an hour down the highway, Josh saw a five-mile service sign and realized he was hungry. More importantly, he was approaching his thirty-sixth hour without sleep and unless he grabbed a coffee soon, bad things were going to start happening. In fact, they already had. A dull grey slowness had settled on him, making his peripheral vision busy with the hazy shifting shapes that severe fatigue specialized in manufacturing, and his limbs were beginning to feel twice their weight. But hungry as he was, he still hadn’t forgotten the affront of yesterday’s dawn. McDonald’s might have sold ten billion, but he wasn’t going to make it ten billion and one.

He thumbed the radio.

‘Any you northbounds know a good place to eat off the interstate?’

The voice first to respond just laughed. ‘Surely, driver. There’s a little Italian place right up ahead. Violins playin’ and candles on every table.’

Josh smiled.

Another driver butted in. ‘No shit? Where’s that at again?’

‘I’m kiddin’, dipshit. Burgers ain’t good enough for you?’

Josh pressed his radio again, then thought better of it. What did these guys know? Channel 19 would be busy now for the next hour with bored truckers arguing about the merits of the great American burger. He was sorry he had started it.

There was an exit coming up on the right, and although the sign declared this was the exit for a bunch of ridiculously named nowhere towns, he braked and changed down. It was twenty before seven and if he didn’t get that coffee soon he’d have to pull over.

The reefer tailing him came on the radio.

‘Hey, Jezebel. See you signalling for exit 23.’

Josh responded. ‘Ten-four, driver. That a problem?’

‘Got a mighty long trailer there to get up and down them mountain roads. They’re tight as a schoolmarm’s ass cheeks.’

‘Copy, driver. Not plannin’ on goin’ far. Just grab a bite and get myself back on the interstate.’

Josh was already in the exit lane as he spoke the last words, the reefer peeling away from him up the highway.

‘Okay, buddy. Just hope you can turn that thing on a dollar.’

‘Ten-four to that.’

‘How comes she got the handle Jezebel?’

Josh grinned as he slowed down to around twenty-five, on what was indeed, and quite alarmingly so, a very narrow road. When he felt the load was secure behind him, he took his hand off the wheel to reply.

‘Aw this is my second rig, and I figure she tempted me but she’ll probably turn out to be no good like the last one.’

He swallowed at that, hoping the ugly thought that it had stirred back into life would go away. The other driver saved him.

‘Yeah? What you drive before?’

Irritatingly, the signal was already starting to break up. Strange, since the guy was probably only two miles away, with Josh now heading south-east on this garden path of a road.

‘Freightliner Conventional. Everything could go wrong did go wrong. Might be mean naming this baby like that. Hasn’t let me down yet. But she’s pretty, huh?’

The radio crackled in response, but Josh didn’t pick up the driver’s comment. It was the least of his worries. He saw what the guy meant. The road was almost a single track. If he met another truck on this route they’d both have to get out, scratch their heads and talk about how they were going to pass. Josh slowed the truck down to twenty and rolled along, squinting straight into the low morning sun that had only now emerged from the dissipating grey clouds, to look for one of the towns the sign had promised.

The interstate was well out of sight, and he was starting to regret the impulsive and irrational decision to boycott the convenience of a burger and coffee. The road was climbing now, and since the exit he hadn’t seen one farm gate or cabin driveway where he could turn the Peterbilt.

He pressed on the radio again.

‘Hey, any locals out there? When do you hit the first town after exit 23?’

He waited, the handset in his hand. There was silence. It was a profound silence that rarely occurred on CB. There was always something going on. Morons yelling, or guys bitching. Drivers telling other drivers the exact whereabouts on the highway of luckless females. There was debate, there was comedy, there were confidences shared and tales told. All twenty-four hours a day. Anything you wanted to hear and anything you wanted to say, was all there waiting at the press of a button.

But here, there was nothing. Josh looked up at the long spine of the hills and reckoned they must have something to do with the sudden stillness of the radio. It unnerved him. The cab of a truck was never quiet. Usually Josh had three things going at once: the CB, the local radio station, and a tape. Elizabeth had ridden with him a few times and could barely believe how through the nightmarish cacophony he not only noted the local traffic report, but also hummed along to a favourite song, heard everything that was said on the CB, and was able to make a pretty good guess at which truck was saying it.

‘How in hell do you do that?’ she’d breathed admiringly after he’d jumped in with the sequel to some old joke someone was telling, only seconds after he’d been shouting abuse at a talk radio host who’d used the word ‘negro’.

‘What’d you say, honey?’ he’d replied innocently, not understanding the irony when she laughed at him. She said after that, if she had anything important to tell him, she’d do it over a badly tuned radio with a heavy metal band thrashing in the background.

Except she hadn’t. Had she?

It had been important, and she’d told it to him straight, her words surrounded by a proscenium arch of silence. Josh flicked his eyes to the fabric above the windshield where Elizabeth’s cheap brooch was pinned. He’d stabbed it in there as a reminder that it had been bought with love but used as a spiteful missile, hoping it would harden him to the thought of her every time the pain of their argument germinated again. But it wasn’t working. It just made him think of her long brown fingers fingering it with delight. Josh wished the trivial memory of her riding with him hadn’t occurred to him, hadn’t made him feel like his heart needed a sling to support its weight.

He leaned forward and retuned the CB as though the action could relegate his dark thoughts to another channel.

Still nothing.

Josh sat back and resigned himself to the blind drive. The next town could be two or twenty miles away, and he was just going to have to live with that. It could be worse. The road was still climbing, but at least it was a pretty ride.

Dogwood bloomed on both sides of the road and on the east verge the rising sun back-lit the impossibly large and delicate white flowers, shining through the thin petals as though the dark branches were the wires of divine lamps. Ahead, a huge billboard cut rudely into the elegance of the small trees. The sign was old and worn, with the silvery grey of weathered wood starting to show through what had once been bright green paint.

‘See the world-famous sulphur caves at Carris Arm. Only 16 miles. Restaurant and tours.’

In the absence of anyone to talk to on the CB, Josh spoke to himself.

‘World-famous. Yeah, sure. The Taj Mahal, the Grand Canyon and the fuckin’ sulphur caves at Carris Arm.’

As if he needed it, the sign confirmed that Josh Spiller was driving around in the ass-end of nowhere, and he was far from happy. If that was the next town, then sixteen miles was way too far. He started to weigh his options. Surely there would soon be a farm gate or a clearing he could turn in. But as the truck climbed it seemed less and less likely. The mountains were a serpentine dark wall, clothed here in undisturbed forest only just starting to leaf, and neither farmland nor building broke the trees’ unchallenged hold on the land. Josh had already driven at least four or five miles from the interstate and the thought of another sixteen was making him consider the possibility of backing up and turning on a soft verge, when without any warning or apparent reason, the road started to widen.

A house, set back in the trees, neat and spacious with the stars and stripes flapping listlessly on a flagpole by the porch, appeared on his right, followed by another three in a row almost identical a few hundred yards further on. No backwoods cabin these, but substantial suburban houses with trimmed gardens and decent wheels parked out front. Josh raised an eyebrow. This was what truckers called car-farmer country. The backwoods of the Appalachians were home to a thousand run-down trailers and cabins, sporting a statutory dozen cars and pick-ups half buried in their field, like the hicks who’d left them there to rot were hoping their ’69 Buick would sprout seeds and grow a new one.

Even on the main routes, Josh had been glared at by enough one-eyed crazy lab-specimens lounging on porches to know that this wasn’t exactly stockbroker belt. The kind of tidy affluence quietly stated by these houses was a surprise. But it was a welcome surprise to a man who needed his breakfast and wouldn’t have to buy it from a drooling Jed Clampit with a shotgun raised at his chest.

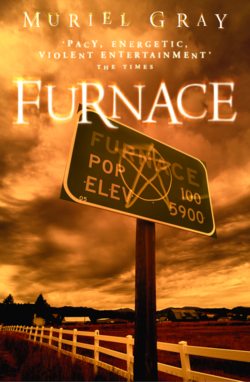

So half a mile and a dozen or more smart houses later, it was with relief that Josh hit the limits of the town to which these uncharacteristic middle-class dwellings were satellites. He drove past the brief and concise metal sign with a smile.

Furnace.

The wide street was now lined on either side by houses only slightly smaller than those on the edge of town. Standard roses bobbed in the breeze and hardy azaleas and forsythia were beginning to form islands of colour in a sea of smooth lawns.

It was five before seven and although it was early, people were about and Josh was heartened by the town’s potential for hot food to go. A kid rode past on a BMX, a sack of papers on his shoulder; two guys sweeping the road stood jawing against a tree, brushes in hand; a woman walking a dachshund on a ludicrously long leash stopped and waved to someone out picking up their paper from the front step. It was cosy, affluent, peaceful and ordinary. But it certainly was not what he had expected high up in this backwater of Virginia. Here, Jezebel felt ridiculously out of place, rumbling self-consciously through the street at little more than running pace, as though lack of speed could hide the bulk and noise of the Leviathan. The quiet street waking to its new day was like any other, but the affluence and suburban smugness was starting to jog a memory in Josh he didn’t like.

The Tanner ice cream sign.

A dumb, irrelevant memory, and one he tried to sideswipe. But it was there.

That ice cream sign.

For Josh as a child it stood at the corner of Hove and Carnegie like a religious icon; a circular piece of tin with the advertisement painted on it, supported at two points by a bigger circle of wire on a stand that let it spin in the wind. Judging by the arthritic squeaking of its rotations, it had stood at the end of his street like that for years, that dismal street his mother had brought them up on, a strange juxtaposition of the classes that Pittsburgh boasted, where the unwashed poor lived only a block away from their bosses, separated by no more than just a strip of trees or a row of stores.

Or an ice cream sign.

The Tanner girl and boy had big rosy cheeks and were licking the same cone of ice cream, vanilla topped with chocolate sauce. But when the wind blew the sign would spin and the picture, identical on both surfaces except for the children’s mouths which were closed on one side and open on the other, would animate into a frenzy of darting, licking tongues. Dean thought the sign was kind of spooky, especially when the wind was strong and the tongues went crazy. But Josh liked it. He liked it because it marked the beginning of Carnegie Lane, and more importantly, the end of Hove Avenue, an end to the crowded street that contained their tattered house. In Carnegie the houses were elegant and tall, keeping watch over their own spacious gardens with the demeanour of large wealthy women sitting on rugs at a race meeting. And unlike the regiment of dreary wooden houses that included the Spillers’, every one was different. Some were brick with wide white columned porches tangled with wisteria and honeysuckle. Others had stone facades and glass conservatories, or European affectations of mock battlements and balustrades. And in addition to the neat front lawns that were uniformly green all the way to the sidewalk, each, Josh knew for sure, had generous and private back yards.

School, the stores and everything that Josh needed to service his uneventful life was at the eastern end of Hove. In other words there was no call to go west into Carnegie at all. It merely led to wealthier parts of town, parts that were decidedly not for the Spillers. But he’d lost count of the times he’d found himself strolling past the squeaking Tanner ice cream sign, stepping into Carnegie with a roll to his pre-pubescent gait that tried to say he lived there.

At least he had until one searingly hot August. Josh was eleven and the day had been long and empty. His mother’s return from her job at a drug factory, moving piles of little blue and white capsules along a conveyor belt all day with a gloved hand, had been a cranky and irritable one. Particularly since she discovered that neither Dean nor Josh had made any attempt to prepare supper, but had instead been throwing stones up at the remains of an old weathervane that clung to a neighbour’s roof, in a contest to free it finally from its rusting bracket.

Joyce Spiller had sat down heavily on the three car tyres piled by the back door they used as a seat, and glared at the boys, but particularly Josh, with tired, rheumy eyes. Her voice was full of sarcastic venom.

‘Sure do appreciate you workin’ all day long, Mom. So to thank you for that act of kindness, please accept this cool glass of lemonade and a big juicy sandwich that me an’ my shit-for-manners brother have had all friggin’ day to prepare.’

Dean had blinked at his boots in shame, but for some reason, looking at this woman in her short nylon workcoat, her thin brown hair tied back with a plain elastic band, and her face that looked ten years older than her numerical age, Josh had suddenly despised her. Why should he look after her, when other kids got to come home from school and be met by a Mom who’d fetch them lemonade and a sandwich? What kind of a raw deal was this, having a mother who worked all day, sometimes nights too, who was always in a foul mood and looked like shit? The absence of a father, a taboo subject in the Spiller house, was bad enough, but the fact that they lived in this shambolic house and never went on vacation was all this failure of a woman’s fault.

Josh had stared back at her with contempt and then run from the yard out into the street.

He thanked God that until her dying day, his mother had taken that action for a show of shame and remorse. It was anything but. He’d seen the Tanner’s ice cream sign slowly rotating in the searing hot breeze and had headed straight for the leafy calm of Carnegie, where the people lived who knew how to treat their children. Maybe if he stopped and spoke to a kid up there, they might get friendly and he’d be asked in. He’d often thought of it. That day he decided he would make it a reality. Then she’d see. She’d come home and he’d be in one of those yards drinking Coke with new friends, who had stuff like basketball nets stuck to their walls and blue plastic-walled swimming pools you climbed into from a ladder. There’d be no more kicking around in a dusty yard with nothing to do except scrap with Dean and wait for a worn-out mother to come home and cuss at them.

He ran as far as the sign, then slowed up and turned into the shimmering street with a casual step. The sign had been making a wailing forlorn sound, a kind of whea eee, whea eee like some forest animal’s young looking for its parent. Josh strolled into the splendour of the street and walked slowly, gazing up at the grand houses, smelling the blooms from their gardens. There had been nobody about except for one man who was rooting around in the trunk of a car parked out front.

Josh got ready to say hello as he approached, but on catching sight of him the man straightened up with legs apart, putting his hands on his hips in the manner of a Marine drill sergeant expecting trouble.

He stood like that, staring directly and aggressively at Josh, never taking his eyes from the small boy until he walked by. Josh had felt his cheeks burn.

It was then that he had noticed the sounds. Just background noises at first, but with the blood already beating in his ears, they grew louder and louder until they were roaring in his head.

Lawnmowers buzzing, children shouting and laughing, garden shears snapping, an adult voice calling out, the echoing, plastic sound of a ball bouncing on a hard surface. All these sounds were being made by a ghostly and invisible army of people cruelly hidden from view. And ever present, weaving in and out of these taunting, nightmarish sounds was the whea eee, whea eee of the Tanner ice cream sign. Josh had been paralysed by a sense of desolation that made his bones cold in the thick heat.

The wall of expensive stone that was separating him from these invisible, comfortable, happy people was suddenly grotesque instead of glamorous, an obstacle that could never be negotiated if you were Josh Spiller from Hove Avenue. He had slapped his hands uselessly to his ears, turned and run back the way he had come, fuelling, no doubt, the fears of the man by his car that this was a Hove boy up to no good. Every hot step of the way home the ice cream sign’s wail followed him like a lost spirit, as though it were an alarm he had tripped when he stepped from his world into the forbidden one of his betters.

His mother had welcomed him back with a silent supper of fries and ham, but he could tell by the softness in her eyes she was relieved to see him. Josh knew then how much he loved her. He also knew that no matter how agreeable a house he might eventually buy as an adult, how comfortable an existence he might make for himself, he would always butt up against the corner of a forbidden street, the edge of something better to which he had no access. Maybe that was why he had turned trucker. No one can judge what a man does or doesn’t have if he’s always on the move. The eighteen wheels you lived on were the ultimate democracy. An owner-operator might be up to his neck in debt with his one rig, or it might be one rig out of a fleet of twenty. No one knows if the guy’s rich or poor and no one cares. The questions one trucker asks another are: where you going, where you from, what you hauling, how many cents per mile you get on that load?

No one would ever ask what street you lived on and give you a sidelong glance if it happened to be the wrong one. Josh hadn’t thought about that dumb incident for years, but here, faced with these attractive houses in this small mountain town, he could almost hear the ice cream sign howling forlornly again. It was crazy. He’d grown into a man to whom material possessions meant little or nothing, and yet here he was being infected by that old feeling of desire and denial that he thought he’d shaken off before he’d even grown a pubic hair. And all because a town looked a little neater, a little smugger, a little more affluent than he’d expected. Okay. A lot more affluent.

Josh shook his shoulders, suppressed his discomfort at the memory as he approached the town’s first set of lights, and scanned the side streets for a sign of something that might suggest food. The truck’s brakes hissed, he leaned forward on the wheel and looked around.

If Furnace had a commercial centre then this was probably it. The wide street that cut across this one was lined on both sides with small shops and offices, buildings that were as well presented as those belonging to their potential customers. There was a cheerful bar on one corner, featuring long, plant-filled windows onto the street, far removed from the darkly terrifying drinking-holes a man could expect in the mountains, and an antique shop on the other that suggested Furnace did a fair piece of business from tourism. A complex metal tree of signs told him where the best Appalachian wine could be bought, provided directions to a children’s farm where the animals could be petted, and reminded you that the world-famous sulphur caves were now a mere fourteen miles away. Josh conceded that bored families in camper vans might tip a few dimes into the town’s economy every summer, but even if they loaded up with Appalachian wine till it broke their axles and petted the farm animals bald, it still wouldn’t account for the prosperity of the town. He mused on the mystery of it, and settled with reckoning there must be a whole heap of prime farmland groaning with fat cattle hiding way back here that was keeping these people in new cars and white colonnaded porches. But if that was the case, they were keeping it well hidden. And although the mountain forest came so close to the edge of the town it made Furnace look little more than a fire-break, what the hell: it was a theory. It made Josh more comfortable to invent a logical and soil-based reason, stalling that tiny and rare niggle of envy he was feeling. He never envied farmers. Being tied to the land was just about the worst thing you could be.

Far down the road to his right, Josh could make out the entrance to a mini-mall, fronted by an open foodstore. That’s where he would head and take his chance, since the parking in front of the store looked sufficiently generous to accommodate the truck.

As he gazed along the long wide road, waiting for the lights to change, the vibration of the idling engine combined with the pale early morning sun shining into his face suddenly made Josh ache to close his heavy eyes. He fought it, but his eyes won.

It must have been only seconds, but when he awoke with a neck-wrenching upward jerk of the head, the fact he’d fallen asleep made Josh pant with momentary panic. He ran a hand over his face. This wasn’t like him. It had been years since he’d allowed himself to become so tired while driving that he could lose it like that. In the past, sure, he’d pushed it. But not now. Once, back in those days when he’d try anything once, he’d driven so long he’d done what every trucker dreads. He’d fallen asleep with his eyes open. After a split-second dream, something crazy about shining golden dogs, Josh had woken suddenly to find the truck already bouncing over the grass verge. He vowed then he’d never do it again. Yet here he was, thirty-six hours since sleep, still driving. He had to stop and get some rest. No question. But first he wanted to eat.

Above him, the bobbing lights had been giving their green permission for several seconds, and he shook his head vigorously to rid himself of fatigue while he turned Jezebel into the street at a stately ten miles an hour. As he straightened up and moved down the road, a car trying unsuccessfully to park pushed its backside out into the road at a crazy angle and forced him to stop. He sighed and leaned forward on the wheel again while the jerk took his time shifting back and forward as if the space was a ball-hair’s width instead of being at least a car-and-a-half-length long. The old fool behind the wheel stuck an appreciative liver-spotted hand out the window to thank Josh for his patience, and continued to manoeuvre his car in and out at such ridiculously tortuous angles it was as though he was attempting to draw some complex, imaginary picture on the asphalt. Josh raised a weary hand in response and muttered through a phoney smile, ‘Come on, you donkey’s tit.’

He sighed and let his eye wander ahead to the foodstore, allowing himself to visualize a hot blueberry muffin and steaming coffee.

Across the street, a woman was walking towards the mall, struggling with a toddler and pushing a stroller in front of her that contained a tiny baby. It must have been only days old. Josh swallowed. He could see the little creature’s bald head propped forward in the stroller, a striped canvas affair, presumably the property of its sibling and way too large for its new occupant. The baby was held level in this unsuitable vehicle with a piece of sheepskin which framed its tiny round face like some outlandish wig.

With the sight of that impossibly small creature, it was back; the longing, the hurt, the confusion that Elizabeth had detonated in him.

He found himself watching like some hungry lion from long grass as the woman kicked on the brakes of the stroller, abandoned the baby on the sunny sidewalk and dragged her toddler into the store. The tiny bundle moved like an inexpertly handled puppet in its upright canvas seat, its little arms flailing and thrashing as two stick-thin legs paddled in an invisible current. Josh ran a hand over his unshaved chin, and covered his mouth with his hand.

Would his baby be kicking like that little thing, right now, inside Elizabeth? When did all that stuff happen? A month? Two months? Six? He knew nothing about it.

Elizabeth. His mouth dried. Elizabeth, his love. Where the hell was she?

He closed his gritty eyes for a moment and the shame of what he had done overwhelmed him, making him light-headed with the sudden panic of regret. Opening his eyes again, he looked towards the infant. There was now a different woman standing behind it, both hands on the plastic grips of the stroller.

Older than the mother, possibly in her fifties, she was dressed in a garish pink linen suit that, although formal and angular in its cut, seemed designed for a far younger woman.

Her hair was red, obviously dyed, and even from this distance Josh decided she was wearing too much make-up; a red gash for a mouth, arching eyebrows drawn in above deeply-set eyes.

He had seen plenty of women like that at the big Midwest truck shows, hanging on the arm of their company-owning husbands; women who spent money tastelessly as though the spending of it was inconvenient and tiresome but part of a dutiful bargain that had been struck.

Josh would barely have glanced at such a woman had he seen one sipping sparkling wine in a hospitality marquee, while her husband ignored her to do business with grim-faced truckers.

But here, standing outside a foodstore in this rural nowhere at seven o’clock on a spring morning, she looked remarkably out of place.

More than that. The most extraordinary thing about her was that she was staring directly and with alarming intensity at Josh. It wasn’t the annoyed and studied glare of a concerned citizen, the look a middle-aged woman with nothing better to do than protect small civil liberties might throw a noisy truck.

It wasn’t aimed at the truck. It was aimed at him.

In front of him, the master class in lunatic parking had ceased, the man at the wheel waving a gnarled and arthritic hand from his window again in mute thanks, and still the woman’s eyes continued to bore into Josh as she stood erect and unmoving, her body unnaturally still, on guard behind the writhing baby. For one fleeting, crazy moment Josh thought he might be inventing her, that a part of his guilty and fevered mind had conjured up this stern female figure to reprimand him for his paternal inattention.

‘That’s right, you useless dick,’ those eyes seemed to be saying. ‘This is what a baby looks like. You can look but you certainly can’t have. Only real men get these. Real men who stay home.’

He blinked at her, hoping that her head would turn from him and survey some other banal part of this quiet street scene, proving that her stare had been simply that of someone in a daydream, but her face never moved and the invisible rod that joined their eyes was becoming a hot solid thing.

There was no question of him stopping at that store now. Josh wanted out of there, away from that face, away from that tiny baby.

He fumbled for the shifter, starting the rig rolling clumsily by crunching his way around the gear-box as he picked up speed. A row of shiny shop windows to his left across the street bounced back a moving picture of Jezebel as she roared up through the gears. It was the clarity of that reflection as it distorted across undulating and different-sized glass that gave her driver an excuse to admire the mirror-image of himself sitting at the head of his gleaming electric-blue Peterbilt, and take his eyes momentarily from the face of the woman who was still standing like a lawyer for the prosecution on the sidewalk ahead.

Had she been waiting for that irresistible weakness that is every trucker’s vanity, to catch a brief glimpse of themselves on the move, and see themselves as others do? Josh would never be sure. How could he ever be sure of anything that happened that morning?

His eyes flicked back from the moving reflection down to the speedometer which showed around twenty, and then looked forward again. Back to the road and those eyes glaring at him from across the street.

She pushed the stroller like an Olympic skater, propelling it forward with a theatrically benevolent outward motion of the arms which culminated in a triumphant crucifix, palms open, shoulders high, as if waiting for a panel of judges to hold up their score cards. The timing and positioning was spectacularly accurate. She hadn’t pushed until Josh had been exactly level with her, so that the front wheels of the stroller rolled at an oblique angle beneath the double back tyres of the tractor unit.

That expertly judged speed and angle let the outer tyre snag the frame and flip it on its side under the rig, giving all eight wheels the opportunity to travel directly over the stroller and its contents.

It was almost as if Josh’s hysterical intake of breath was the force which pulled his right leg up and slammed his foot down on the brake. But there was little point in the action. His chair had already bounced in response to that small shuddering bump, the slight motion the truck’s suspension registered as it negotiated a minor obstacle, the same motion that would indicate Jezebel had run over a pothole or a piece of lumber on the highway. Only this time it wasn’t a piece of lumber. It was eight pounds of brand-new flesh, bones and blood, strapped into its flimsy shell of plastic, aluminium and canvas.

The force of the braking threw Josh forward into the steering wheel, and after he whiplashed back with a winded grunt he snapped his head round, eyes and mouth as wide open as the muscles were designed to allow, wildly scanning the view from his open window as he panted for breath. In those few seconds that felt like minutes, he noticed three things. The first was that the woman in the pink suit was gone. The second was that the reflection in the store window showed him quite clearly that there was a small mangled mass beneath the trailer, caught untidily between the back wheels of the cab. The third was that the mother was emerging slowly, as if in a dream, from the door of the store, her mouth making a dark down-turned shape that was impossibly ugly. It took a few more seconds before her screams started. First her arms twitched at her sides and her body appeared to quiver with some internal electric current, and then it was as if that current had been suddenly cut. She collapsed to her knees like a prisoner about to be executed, and her dark open mouth shaped the cry that savaged the morning air with the naked brutality of its pain.

Behind her, in the open doorway, her toddler stood howling until adult arms swept it inside.

Josh was out of his cab and scrambling desperately beneath the trailer before he had time to consider what he might find there. Had he stopped to think he would never have approached that soup of flesh, but his body was working to some private agenda that had little to do with logic or thought. It moved and acted on instinct, as if unthinking swiftness of action could somehow undo what had most certainly and irreversibly been done.

The towelling one-piece babysuit had held most of its contents together, but it had expanded when the body inside changed shape, so that now it was not so much a garment as a large, sticky, flat sack. The blood seemed so thick and black, but the worst of it was the way the main aluminium support of the stroller had embedded itself in the middle of the baby’s skull, splitting the head in two in a diagonal line from one eyebrow to a tiny shoulder. It had forced both eyes from their sockets before they, too, were mashed into the glistening corpse.

Perhaps he thought the child would be unrecognizable. He was disappointed. The mess was still so obviously a baby that Josh put out a trembling hand and fingered one tiny foot that had somehow remained intact, regretting it instantly when his gentle touch made it shift slightly with a sickening slick sound. For a crazy moment, lying on his stomach beneath the trailer, he thought about those cartoons where the victim is run over by a road roller and peeled off the road in a long flat strip, and he wanted to laugh.

He wanted to shake with laughter, wanted to feel tears of mirth pour down his cheeks, and hold his sides as they ached with the effort of hilarity. But the sound he was already making, accompanying the stream of salty tears dripping from his chin, was a thin, reedy wail that came from the back of his throat. It was a sound very far away from laughter.

He lay there for a long time, then there were hands on his legs, pulling him out from under the truck. Gentle hands, squeezing him reassuringly as they tugged him back. And voices. Calm voices that sounded miles away, saying things like ‘come on now, fella’, ‘leave it now’, ‘come on there’.

Josh went limp. He was pulled free of Jezebel by three pairs of hands and manhandled into a sitting position. A man wearing thick spectacles and a blue cotton coat with ‘Campbell’s Food Mart’ stitched on the pocket, was kneeling in front of him, looking concerned.

Behind him were two lanky teenagers, one with the same coat and one in a T-shirt and low-slung jeans. The man was talking softly, as if to a wounded animal.

‘S’okay. S’okay now. Weren’t nothin’ you could’ve done there, fella. Sheriff’s on his way. You just sit tight.’

Josh looked at him dumbly and then turned to the sidewalk in front of the store where he had seen the mother collapse. She was sitting as he was, although being attended to by more people, but her head was thrown back and one arm reached up above her head as though trying to grab a rope. The woman, the woman in pink, that staring, crazy murderer, was nowhere to be seen. Josh realized with an accelerating panic she was not being pursued, that her absence was not an issue here. She had to be found, had to be stopped. He struggled to get to his feet.

‘It wasn’t no accident … listen … we have to find that woman … she …’

The bespectacled shopkeeper held him down.

‘Hey, hey. Come on there. You had a mighty bad shake-up. Hang on in there.’

A station-wagon ambulance was drawing up, and suddenly the hands that were pressing his shoulders down now went to his armpits and helped him to his feet.

He went meekly and sat down heavily on the edge of the sidewalk where his assistants abandoned him in favour of a split interest between the hysterical mother and the two paramedics crouching under the trailer. To Josh, the people making up this macabre tableau were moving slowly and dreamily as though they were under water. He blinked as a fat, dusty police car rolled to a halt behind the truck and watched impassively as a sheriff’s deputy climbed into Jezebel and moved her to the side of the street with a shudder of badly-changed gears.

He said nothing as a square man who claimed to be the sheriff led him to the police car and gently guided him into the back seat. But as they drove off, his armour of numbness was shattered by the sight of the bereaved mother, still sitting on the sidewalk, now embraced clumsily around her thin shoulders by a rough-hewn man in paramedic’s coveralls. She lifted her head as he sat in the police car, raised a trembling hand towards him and opened her mouth to speak. He waited, steeling himself for the abuse, the unimaginable but inevitable verbal wounding.

With the window shut he couldn’t hear her words, but her face was so close, and she spoke so slowly he could lip-read as clearly as if she had shouted.

Josh’s heart lurched as he watched her mouth say, ‘I’m sorry.’ Then she bowed her head and gave in to her weeping once more.