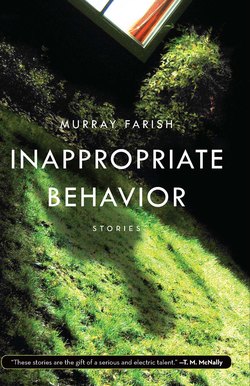

Читать книгу Inappropriate Behavior - Murray Farish - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE PASSAGE

It was an unseasonably chilly morning in late September, 1959, when Joe Bill Kendall waved to his parents from the aft deck of the freighter Marion Lykes. They’d left Tyler at 3:00 a.m. to get him to the boat on time and to save the expense of a New Orleans hotel room, and now his parents looked, to Joe Bill, small and tired and, his mother especially, slightly worn, the way she kept waving, wiping her face, waving and wiping her face. Although he had not slept the night before, Joe Bill felt no fatigue at all, just the same excited strum in the gut he’d had for several weeks.

After a few minutes of waving, watching his parents grow tinier and tinier—although the ship had not yet moved—he blew one last kiss good-bye and turned, took his luggage cart by the handle, and headed toward the passengers’ deck, hearing nothing but French the whole way. He passed some of the deckhands tying down loads and marking the inventory, and understood every word. He passed a pair of officers discussing their plans in Le Havre and picked up most of that as well. It was soon clear that nearly the entire crew was French.

Joe Bill made a sudden decision not to let on that he spoke the language. It would be fun; it would make him feel like a spy on a secret mission, not just a kid going abroad for a few months of study on the cheap. At the exact right moment, he could spring it on some unsuspecting officer or deckhand, respond to some slight about Americans or some clever quip or worldly statement. They’d look at him, stunned, amazed, with a whole new respect. The man, they would think, is more than he appears.

Joe Bill’s cabinmate was already in the room when he arrived, lugging his cart behind him through the narrow hallways of the passengers’ deck. Joe Bill was a little disappointed; he’d hoped to be the first.

“I’m Lee,” the other man said. “I don’t mind the top bunk.” They shook hands, and Lee looked off to the side of Joe Bill, behind his back and to the left.

He was a slight young man a few years older than Joe Bill, dark brown hair and a knobby chin, small, dark eyes beneath dark, large brows.

“So what brings you aboard the Marion Lykes?” Joe Bill asked as Lee untied the gray denim duffel that was apparently his only piece of luggage. He took out three dark pairs of slacks, four or five white button-down shirts, a handful of underwear and undershirts, some socks. The drawer was only half full when Lee was done with the clothes. He threw the duffel, still containing some weight, onto his upper bunk.

“I’m going to college,” Lee said, kneeling back down beside the drawer.

“Me too,” Joe Bill said. “You going in France?”

“No,” Lee said, not looking up at Joe Bill, still fiddling with the clothes in the drawer, lining them up straight and pressing them out flat. “Sweden.”

“Sweden,” Joe Bill said. “How about that? Cold up there.” Lee appeared to have only the coat he still had on, a green military field jacket. “And dark six months of the year.”

“Or Switzerland.”

“Oh,” Joe Bill said. “So you haven’t decided?”

“Switzerland.”

“What school?”

“What about you?” Lee said, looking directly at Joe Bill for the first time, then quickly looking back into his drawer. He set each ball of socks next to the other in a tight, lumpy row.

“I’m going to study at the Institute in Tours.”

“How old are you?” Lee asked, setting his eyes on Joe Bill again.

“I’m seventeen,” Joe Bill said. This always made him nervous. He was old for his age, or acted older, and when people found out how old he really was, they did one of two things. They either dismissed him as a child or they went on and on about how smart he was for seventeen, how mature, which was just another way of dismissing him. He’d lied about it a couple of times, but the lies made him feel bad, like there was something wrong with him for being the age he was, like it was shameful somehow. He decided that rather than lie and be ashamed, he’d tell the truth, and when they dismissed him, he’d tell himself that they wouldn’t be able to dismiss him for long, that he was way ahead of the game. He was on his way to France, going there on his smarts.

“Seventeen, huh?” Lee said. “I joined the Marines at seventeen.”

“How about that?” Joe Bill said. “A vet, huh?”

“Yeah.” Lee stood from the drawer, shut it gently and turned his back to Joe Bill. He reached into the duffel again and pulled out a couple of journals and some pencils, and as he did, a little black plastic rectangle rolled out onto the bed. Lee quickly tucked the thing back into the duffel.

“So where were you stationed?”

“All around,” Lee said, setting the books and pencils on the desk at the foot of the bunk beds. The cabin was close, and Joe Bill had to step back to let Lee in between him and the edge of the desk. But Joe Bill also realized he’d leaned in some as they’d talked, both because Lee had turned his back and because of the black plastic object Lee obviously hadn’t wanted him to see. Now as Lee stepped by, Joe Bill backed up almost out the door, nearly tripping over his three suitcases that still sat there on the cart. “California,” Lee said. “The Philippines.”

“Wow.”

“Japan.” Lee neatly lined up the journals atop the desk and put the pencils in the top drawer.

“And now to Switzerland,” Joe Bill said, moving back into the cabin, putting some six or eight inches between the suitcases and his heels. “That’s fantastic, really. You on the GI Bill?”

“Are you planning to unpack or just trip over those things the whole time?”

Joe Bill took the three green Samsonites off the cart and into the cabin, leaving the cart outside in the hall. He strapped two of the suitcases in the rack beneath the lower bunk and set the third atop the dresser. When Joe Bill popped the locks, the first thing he saw inside was the red leather Bible. Lee saw it, too.

“So you’re a Christian?”

“Well, yeah,” Joe Bill said. Religion was another topic that embarrassed him. He was a Christian, he supposed, in the sense that he’d gone to the First Baptist Church of Tyler every Sunday morning and Wednesday night since he could remember, like everyone else. But he hadn’t brought the Bible on purpose, had little interest in the subject, and certainly didn’t want to discuss it here.

His mother had worried about him going to France, a Catholic country, because she thought the people there were drunken and promiscuous. He’d gone, at her insistence, to see Reverend Dunn, who’d asked him if he thought he was strong enough to weather the storm of the Papists, if he was prepared not only to stand up for his own faith but to witness to the benighted French as well. He reminded Joe Bill of his duty to be a fisher of men. He’d written something illegible in his shaky old hand on the inside cover of Joe Bill’s Bible, and his mother had packed the Bible with his clothes.

“Humph,” Lee said. He was sitting on the top bunk now, leaning his back against the cabin wall.

“I mean,” Joe Bill started, stopped, said, “heck, I’m just a guy from Texas. We’re all Christians. But I’m no preacher or anything.”

“But you believe in God.”

“Yeah, but—”

“There’s no God.”

“Well, you can—”

“How can you believe in God in the light of science?” Lee said, his voice rising to a higher pitch, his palms out-turned in front of him. “Science will one day prove everything, figure out everything. God’s something people needed when they lived in the Dark Ages. Step into the light of science, pal. Science is the only god.”

“Well, now,” Joe Bill said, “I don’t know.” He felt funny about saying all of this to someone he’d just met. But Lee was so sure of himself, somewhat hostile, and Joe Bill felt that to merely back down, or worse, to admit that he agreed with Lee, would make him seem weak, childish, like someone who didn’t know what he thought about things. “I don’t think God and science exclude each other.”

“But if you say that, you’re still holding on to the old ways of thinking. You can’t water it down by saying it’s part God and part science or that God controls science. God doesn’t control anything. Nobody controls anything, or anyone. You still want to think that there’s someone in charge. There’s no one in charge. We’re all just alone, on our own. There’s no force but science. There’s no supreme being. There’s nothing but matter, and anyone with any intelligence can see that.”

With that said, Lee slid off the bunk to the floor, moved quickly past Joe Bill and out of the cabin, pausing to step over the luggage cart. And thus ended the longest conversation the two men would have for some time.

Over the next several days at sea, Joe Bill realized that Lee was avoiding him. Joe Bill had always been an early riser, but he was never awake before Lee, and when Joe Bill went out onto the deck, Lee would go back to the cabin. If Joe Bill went back to the cabin, Lee would get up from the desk, close and lock the journal he was writing in, put the pencil back precisely in the desk drawer and go back out onto the deck, casting only the quickest of glances over his shoulder at Joe Bill. At meals the ship’s four passengers shared a table—Joe Bill, Lee, and the Wades, an older couple who were on their way to visit France following Colonel Wade’s recent retirement from the Army Signal Corps. The Wades would sit next to each other on one side, Joe Bill and Lee on the other, Lee always sitting directly across from Colonel Wade and eyeing him suspiciously while they ate. The Wades got along with Joe Bill well enough, but they were always trying to engage Lee, who would answer their questions with blunt, toneless replies and never follow up with questions of his own. Mrs. Wade especially seemed fond of Lee. She’d ask him about his plans of study—“psychology or philosophy”—where he was from—“New Orleans”—if he had a wife or a girlfriend—“no”—and what he wanted to do with his life. Lee merely shrugged and continued eating.

One night, four or five days into the passage, about the time the days became a haze of wave and fog, the four of them were sitting at dinner. Colonel and Mrs. Wade had been talking to Joe Bill about his parents back home in Tyler, and Joe Bill had been giving them the standard stories. When she turned and asked Lee about his parents, Lee just stared for a long moment at Colonel Wade, glowering more than usual. Then he shook his head, blew out a high, sharp laugh, and set his fork down next to his plate. The ocean was rough that night, and the fork rattled against the plate as Lee began to speak.

“My father’s dead,” he said. “I’ve never seen him. My mother has to work at a drugstore to support herself. She’s old and sick and frail and has to work at a drugstore. There’s America for you. They’ll put her out on the street if she doesn’t keep the rent coming in. Put her in jail if she doesn’t pay her taxes. She’s never gotten anything for it, either. Just a sore back and wrinkled, calloused hands and off to work again at the drugstore. There’s America.”

“I’m sorry,” Mrs. Wade said, surprised. “I didn’t mean to pry. I was just—”

“Home of the free,” Lee said now, slapping the table and sending his fork to the floor, where it slid against the bulkhead and rattled there even louder. “Land of plenty. Hah! Land of a sickness and a cancer. A cancer called money. It eats you and eats you. And when it’s gone you’re dead. Or wish you were.”

“See here,” the colonel said.

“I’m so sorry,” Mrs. Wade said.

Joe Bill said nothing. The officers at their table had stopped eating to stare at the scene. The steward had entered the room at the sound of shouting and stood at the corner of the passengers’ table saying, “Please, monsieur,” and Lee was still going on, and now he stood and the colonel stood and said, “Calm down,” but Lee was waving his hands and shouting about America and how it robbed people of their lives and their blood in order to keep the rich in fine clothes and fancy cars, and then he said, “And men like you, Colonel, your job is to keep the poor people in line. The state only gains its power through fear. Except in America, you can even convince people it’s not fear at all, but duty and honor and country and national pride that keeps them going off to the factory and the plant and the drugstore.”

“Sit down, please,” Mrs. Wade said now, and the steward said again, “Please, monsieur. Sit, please,” and Joe Bill watched as Lee said, “Colonel, I know. I was a soldier, too, you understand.”

“You’re some kind of damned communist,” the colonel said now, pushing his wife’s hand away as she reached for his.

“No, I’m not,” Lee said. “Communism’s just another tool of the state. Just another illusion. I’m a Marxist-Leninist-collectivist.”

“I knew it,” Colonel Wade said, ruddy and livid, pointing at Lee. “Why don’t you just keep going? Don’t stop in Sweden or Switzerland or Denmark or wherever it is you’re going. Just keep on. You’d be happier in Russia.”

“My mother would be better off there, that’s for sure,” Lee shouted, then pushed his way past the steward and out the door.

“I am very sorry, gentlemen,” the steward said. “Very sorry, madame. It is the ship, certainement. It is not a luxury liner, no? Some people get upset . . . how you . . . cramped? It makes some people . . . irritable. I will try to have a talk with monsieur Lee. If necessary, we will make other dining arrangements.”

“Of course,” Mrs. Wade said as Colonel Wade returned to his seat with a snort. “Of course, it was my fault, really,” she said. “I shouldn’t have pried. I could tell he was sensitive.”

“He’s nuts,” said the colonel now, picking his glass of tomato juice from the holster and bringing it to his face.

“Again, please accept the apologies of the captain and crew of the Marion Lykes.” With that the steward spun quickly away. Colonel Wade turned to Joe Bill.

“Is he like that all the time?”

“To tell you the truth, sir,” Joe Bill said, “he really never speaks to me. We talked some the first day, but since then he’s hardly said a word. I don’t really see him that much, actually. I have no idea where he goes. Just wanders around on the deck, I guess. He’s gone when I get up in the morning and still gone when I go to bed at night.”

“The poor thing,” Mrs. Wade said. “I should have just let him be. I have a problem with talking too much, don’t I, Richard? I always have. I just had to pry.”

“It’s really quite amazing,” Joe Bill said. “It’s like he vanishes or something.”

“This is 1959,” Colonel Wade said now. “No one can still be that naive about communism. Not after Korea.”

“A mother would have known better. I was never a mother. Female troubles.”

“It’s not that big a ship. There are only so many places he could go.”

“Not after Stalin.”

And the three of them went on like that for the rest of the meal, each in their own conversations, their own attitudes of sympathy, mystery, and disbelief, until the steward came again to clear the table, and Joe Bill and the Wades said goodnight.

And now another week, or four days, or ten days, had passed. The sky in the daytime was the color of smooth lead, and at night no stars came out and the dark was low and cloying, like the sky had dropped down to meet the water and seal the Marion Lykes inside, holding it in place somewhere far away from the port of New Orleans or the port of Le Havre, and there it would stay until the waters dried up and the sky squeezed the earth into nothingness, until all that was left was matter, and then not even that.

If only he’d spoken his French earlier, he would have someone to talk to, the deckhands or the officers. Joe Bill imagined them up late with a drink in the mess discussing Baudelaire or de Gaulle as the mooring chains clanged against the bulwarks and the ship gently pitched through the night toward France.

His spy game had been a bad idea. That was clear. But it was also clear that to suddenly start speaking French now would seem rude at best, make him look like he really had been spying on them, and they would certainly distance themselves from him even more. By keeping his secret, at least he could still listen.

On one of these starless, heavy nights, Joe Bill went out on the deck for a smoke, hoping to eavesdrop on the deckhands while they worked. It was starting already, his mother would say if she saw him flicking four, five, six matches before he could get one to light, the collar of his overcoat turned up against the ocean chill and scratching against the stubble he hadn’t shaved in a couple of days. Hasn’t even got to France yet and already he’s smoking. And the truth was, he didn’t even like it, didn’t even know how to smoke, but he was so lonely and bored that so many times smoking a cigarette was the only thing to do. He’d bought his first pack of Chesterfields—the only American brand on sale in the ship’s mess—sometime shortly after the blowup between Lee and Colonel Wade at dinner, the last meal Lee had shared with them. And now Joe Bill was already up to a pack a day because he didn’t feel like he could just go stand outside and not smoke, and he was going outside all the time. It was a shame, Joe Bill thought, puffing his Chesterfield, that he and Lee hadn’t hit it off. They could have been pals—nothing like the hothouse of a freighter cabin to form fast friendships. They could have visited each other this fall—Lee could have come to Tours and Joe Bill could have gone to Switzerland (or Sweden or Finland). It was a shame, but it was unlikely to change now.

It was after dinner, and the Wades were on deck as well, but across the ship, at the bow, and just as Joe Bill started over to talk with them, they briskly turned to go back inside, Mrs. Wade tucked under her husband’s arm against the cold. Joe Bill waved, but the Wades didn’t see him, and again he felt the kind of utter loneliness we can only feel when there are other people around to amplify that loneliness. The Wades, the deckhands, the officers, they all had each other, and Lee, well, Lee seemed to want nothing more in life but to be alone, and thus wasn’t really lonely.

Joe Bill was pacing now, counting his slick-shoed steps like a man in prison. The urge to fling himself into the water actually entered his heart, only failing when the urge reached his mind. It wasn’t death he wanted, just a new medium, a new color besides the gray steel of the boat, the grayer steel of the sky. He began to rehearse the letter he would write to his parents as summer neared and it came time to return home, the letter that would beg, cajole, demand the terrible expense of airfare. And as he crushed out one cigarette and reached for another, he heard two of the deckhands speaking in French about the “young American.”

He couldn’t tell where their voices were coming from at first, but soon he realized he’d made his wandering way down by the cargo stacks. Among the boxes strapped and tarped there, the men must have made some space for themselves to be alone, away from the captain or the mate or the steward.

“He was in the engine room, drawing something in his book,” one man said, and Joe Bill realized it was not him they were discussing, but Lee.

“He is a strange one.”

“Then Thierry found him in our cabin.”

“I’ll kill him.”

“And Thierry said to him, ‘But monsieur, surely you know this area is private.’”

“And he said?”

“He said he was lost.”

“Lost at sea.”

“Thierry said, ‘Yes, monsieur, it happens. This ship all the decks look alike.’”

“Uh-huh.”

“And the American says, ‘In Russia, where I’m going, there is no private property. I can come into your room any time I like. And you into mine.’”

“So it’s Russia, now?”

“And Thierry says, ‘But monsieur, this is not Russia.’”

“Naturally. And the American said?”

“He said he was sorry and left. But it was what he said as he was leaving that is the point.”

“What was that?”

“He says, ‘Ask your captain why this passage is taking so much longer than usual.’ He says, ‘Ask him about the other boat, the one that met us last night, and the people who got on and off.’”

“What?”

“That’s what he said.”

“He is a lunatic.”

“But it is taking longer.”

“Conservation of fuel. Budget cuts. Low-paying passengers. I was up all night. There was no other ship. He reads too much.”

“Did you hear anything?”

“Michel, do not be a fool. We are in the middle of the ocean. And we are heavy, too. And the wind is against us, and it is autumn.”

“It is taking longer than usual.”

“When we land, you’ll see that nothing has changed.”

“Let’s hope.”

“Your hope will be rewarded.”

So in addition to being surly and rude, Lee was a sneak, probably a thief. And crazy. You could never know what someone was up to. What was this business about Russia? What could Lee have been drawing in his notebook? What was he always writing in those journals? This nonsense about another boat meeting up with them? Why did he have that tiny camera? Joe Bill was sure now that what he had seen fall from Lee’s bag that first day on board was a camera. It was no bigger than the pack of cigarettes he now pulled from the inside pocket of his overcoat. Again he struggled to light his smoke.

After a couple more cigarettes, Joe Bill went back inside. It was still too early for bed, and he wasn’t tired, but he was going to go into his cabin and read in his bunk until he fell asleep. He didn’t care if Lee was in there anymore. He was tired of feeling like he was the one who was wrong, like he was the intruder. He wasn’t some boy to be pushed around; he was a man, and it was his cabin, too, and if Lee didn’t feel like sharing it in a civil manner, that was his problem. But when he brusquely opened the door of the cabin, Lee was not inside.

When you’ve lived in a place so small for as long as they had (how long now?), you can feel before you even see it that something is out of place. Joe Bill took off his overcoat and loosened his tie and looked around the cabin. It just felt wrong, but only barely wrong, like the motion of the ship had shifted things around. He sat down on the bottom bunk to unlace his shoes, then quickly kneeled on the floor to check his luggage. It was there, securely strapped just as he’d left it. He stood again and unbuttoned his sleeves, took off his shirt and hung it by the collar from the hook at the foot of the bunk, and when he did, he saw what was out of place.

One of Lee’s journals was lying open on the desk. They usually sat, carefully locked, one atop the other in perfect order, but tonight he could see the words on the page, if not make them out.

This was not good. Lee never left the journals opened. Every time he got up for even a moment, he’d close and lock the tiny hasp of the journal and return it to its spot at the edge of the desk.

Had he just gone down the hall to the bathroom and forgotten to lock this one? Or was it some sort of a trap? There was no right thing to do. If he closed and locked the hasp and returned the journal to its place, Lee would know. If he left it there and Lee hadn’t done it on purpose, he’d think Joe Bill had opened it. If he just got dressed again and left the cabin, acted like he’d never been there? This might work, but what if Lee should walk in while he was dressing, and wonder why, and see the journal open there?

He’d never been like this before this trip with the lunatic Lee. He’d never had to worry about being a sneak or a louse because he wasn’t one, and so he had no idea how to get out of looking like one now. There was no reason for anyone to be suspicious of Joe Bill, but Lee certainly would be. There was no reason for Joe Bill to be suspicious of himself. Lee had done this to him, with his sneaking around and disappearing and never talking to anyone except to say something awful and rude and arrogant, and how could anyone get along with someone like that?

Well, damn it all. He’d walk over there like a man and close the damn journal, and if Lee so much as asked him about it, Joe Bill would let him have it, but good. Or to hell with it, leave it open, just like he found it. No, close it. That’s the thing to do. That’s what a man would do, and if he were asked about it, he wouldn’t let Lee have it. He’d calmly tell Lee that he’d left the journal open—or anyway, that the journal was open on the desk when he came in, and he’d simply closed it out of respect for Lee’s privacy, because two men sharing such close quarters should have respect for each other. That was the idea. He walked to the desk.

And he wouldn’t have read a word if the first thing he saw hadn’t been this:

I here by renounce my citezanship in the United States. I take this action with all understanding. I am not doing this lightly or with out thought. I plan to seek citezanship from the suepreme Soviet in the USSR. I have made my desision for political reasons and it is final.

Joe Bill began to flip through other pages in the journal. Each page he saw was a variation of the same theme, the same message, the same erratic spelling. On other pages was writing that Joe Bill recognized as Cyrillic, in the same hand—row after row of the same words, also in slight variations, which Joe Bill knew were conjugated verbs. So Lee had a secret language, too—Russian. There was a loose scrap in the journal that said: S. Bulgakhov, svt emb, Helsinki. On another page was row after tighter row of signatures: Alek Hidell, Alek J. Hidell, Alex Hidell, A. J. Hidell. On a page near the end he read: The actions of nations can be easally understood, but the actions of human beings are unfathamable.

It was one thing to talk about communism, even one thing to be a communist or a Marxist or whatever Lee was. It didn’t bother Joe Bill, at least not to the extent that it had bothered Colonel Wade. But for a man—especially a veteran—to defect to the Soviet Union, this was another thing altogether. For a man to have contact information at a Soviet embassy. And that little tiny camera, and sneaking around the boat, and who was Alek Hidell? And now the question was, what to do about it? He could go to the ship’s captain, explain the whole thing, how the notebooks were open and he had never meant to look at them, but now that he had, the captain had certain responsibilities. He could wait until the ship docked—surely it wouldn’t be but another few days—and go to the first US consulate he could find, tell them about Lee and his plans. Or he could go to Colonel Wade and see what he thought. He was still flipping through the pages of the journal when he heard Lee say, “I haven’t been reading your Bible, Joe Bill.”

He turned to find Lee standing right next to him, practically over his shoulder, and Joe Bill realized that at some point, without knowing it, he’d actually sat down in the desk chair to read the journals. Now he stood, too quickly, and the chair fell back against the floor. Lee was standing close, and Joe Bill tripped over the chair and bumped into Lee as he stumbled past. Lee calmly went to the desk, looked at the open journal for a moment before looking back to Joe Bill with just the barest hint of a smile. He did not speak.

“I’m sorry, Lee,” Joe Bill said, trying to get his legs beneath him for the fight he was sure was coming. “I came in and the thing was sitting there open, and I know you never leave them open, and I was going to close it when I saw . . .” He was silent then.

“What did you see?” Lee said, after several long seconds passed.

“I saw what you’d written there.”

Lee looked again at the open journal, the Cyrillic words. “You saw where I was practicing my Russian?”

“Yes,” Joe Bill said, slowly balling his fists.

“I didn’t get to go to college,” Lee said. “We couldn’t afford it. I joined the Marines. And pretty soon in the Marines, you realize that you’ve got to have something to keep your mind working, or you’ll go nuts. I studied Russian, taught myself how to speak it and read and write it. I taught myself. Pretty smart, huh?”

“It is, Lee,” Joe Bill said.

“Well, you caught me, huh? I study Russian. I guess that makes me a suspect now.”

“No,” Joe Bill said. “I think it’s very impressive.”

“Well, I’m glad for that, Joe Bill. I sure did want to impress you. That’s the most important thing in the world, isn’t it? For underlings to impress their betters. That’s what makes the world go ’round, right? That’s what keeps the machine turning. Be a good boy and I’ll throw you a bone.”

“Lee, I don’t think I’m your better.”

“You think you’re everyone’s better,” Lee said now, slapping the journal shut and moving toward Joe Bill, who took a few steps back. “You’re so young and so smart. A little too smart, aren’t you? Want to be a big man, but you’re always playing games. You think I don’t know about your game?” Lee was standing right in front of Joe Bill now, pointing at him, nearly poking him with his finger.

“What are you talking about?”

“The way you listen to everyone all the time. You think I don’t know you speak French? I can tell by the way your ears prick up when the officers are talking at dinner. And you’re not just getting a word or two here and there. You speak good French. I’ve watched you listening to the crew. They probably know, too. You’re not exactly subtle about it.”

Joe Bill could feel himself moving ever closer to the door of the cabin as Lee continued to advance. He wanted to disappear. Joe Bill had sneaked around like some sort of spy the entire time he’d been on board, and for no reason at all other than to make himself feel superior—like a mysterious, grownup man, with his school-taught French and his smarts and his damn cigarettes, which he wanted now very badly. They were in the pocket of the overcoat that he’d thrown carelessly over the top bunk, another thoughtless invasion of Lee’s privacy and space. And as he stood there and looked at it all, not just all he’d done that night but all he’d done the entire trip, although Joe Bill was not physically afraid of the smaller man, he wished he could take a beating for it, and he thought he knew how to make it happen.

“I also saw the other things,” he said. Lee stopped pointing and stood back from him, quiet for a moment.

“What other things?”

“The thing about renouncing your citizenship,” Joe Bill said. “The signatures. The little camera. All of it.” He relaxed himself completely to take the first blow. But it didn’t come.

Instead Lee turned and went to the bunks. He took Joe Bill’s overcoat from the top bunk and folded it neatly on Joe Bill’s bottom bunk. He then pulled himself up onto the top bunk and sat cross-legged facing the desk. “Sit down,” he said.

When Joe Bill didn’t move, Lee pointed to the overturned chair and said again, “Sit down.”

Joe Bill moved slowly toward the chair, picked it upright, and sat there. Lee sat very still and looked down at him from the top bunk.

“This is important, Joe Bill, so I want you to listen to me, okay? This is the most important thing you’re ever going to hear in your life.”

Joe Bill nodded.

“There is a very good chance that there’ll come a day, maybe soon, maybe not, but it’s coming, when you’re not going to want to have had anything to do with me. People may come and ask you about me, about how we spent this time together on the ship for France, and what do you remember about me, what kind of person was I? And they’ll hound you about this.”

Lee stopped talking for a moment and brought his hands in front of him and crossed them there. Joe Bill, looking up at Lee, began to feel the strangest moving sensation in his chest, and for a moment he couldn’t place its familiarity. But as Lee leaned in a little to speak again, as he took a deep breath, Joe Bill knew it was, of all things, the urge to cry.

“Now, this is the important part. You’re not going to be able to say you never knew me. But you’re definitely not going to want to tell them you read my journal or that you knew anything else about me. The camera, for example. You never saw the camera, understand? The thing to say is that I was strange, and quiet, and that when I did talk, I was spouting off about communism. Got it? Maybe you can even say I didn’t believe in God, but no more. Because if you do, Joe Bill, you’ll regret it. They’ll destroy you. And you’ve got a good life to go lead, so don’t mess this up. Strange, quiet, kept to himself, communism. That’s it.”

Joe Bill tried to nod, but his lip quivered. This was ridiculous. He hadn’t cried since he was a child, had never had a reason to, and he didn’t have one now, and yet he felt his cheeks tighten and his mouth dry up, and he fought, with all he had, the need to wipe his eyes. And then the tears started, and that night on the boat would be the last time he would cry until that terrible afternoon four years later when he next saw Lee Harvey Oswald, on television, being led away in cuffs and screaming, “I’m just a patsy!” while reporters bumped his bruised and beaten face with microphones. Two days after that, he saw Lee shot to death in the basement of the Dallas Police Department by Jack Ruby, and the tears came again, right in front of his fellow airmen in the rec room at Bergstrom, Joe Bill only hearing over and over again what Lee had said to him that night on board the Marion Lykes: “It’s like this, Joe Bill. Remember the story from your Good Book about Peter, and how he denied Jesus three times? Well, pal, I ain’t Jesus, and you need to deny me as many times as they ask.”

And they did come and ask, although they didn’t hound him the way Lee had said they would. The men from the FBI asked a few simple questions, and Joe Bill gave them Lee’s answers, which seemed to be the answers they wanted, and they went away. And he told the Warren Commission, and they sent him away. And the reporters came, and Joe Bill said the same things to them. Over the years, people who were writing books about Oswald and the assassination would turn up, and they’d ask Joe Bill the same questions, and Joe Bill would tell them the same things, maybe a little more here and there, but he’d never say the big things, never ask his own questions: Why did Lee go to Russia, and for whom? Who supplied Lee with tiny cameras and contact information at Soviet embassies? How much of his life was an act, a game? How much was a story, and how much was real? What did Lee know in September 1959 about November 1963? He couldn’t possibly have known that he would assassinate a president who wasn’t even president yet. But he’d known something, certain as death.

And, of course, there was the biggest question of all. It was there, asking itself, the day his son was born and the day his first wife died. The day he awoke in the hospital bed after his heart attack, it was there. Every morning as he drove alone to work, on his pillow in whatever company house or roadside motel he slept in as he followed the dry holes and gushers of the west Texas oil industry, it was there. It’s been with him every day since and will be forever, and it’s the one question he has an answer for: What did you do about it, Joe Bill? And the answer is, nothing.

Joe Bill never has told his whole story. He’s slept and eaten and lived and loved with all his shaky knowledge and his shadowy questions in his own mind alone, all of this set against the one true fact he knows: that he’s failed, somehow. Failed Lee and America and himself and his children. He’s failed in part because it’s too difficult to keep it all straight in his head. All the information is confusing and confounding. There’s simply too much of it, with the books and the commission reports and the evidence and the documents. He’s failed in part because time has passed, and now the whole thing was a long time ago, and no one’s asking anymore. Mostly he’s failed because he knows the stories about the million-to-one accidents and sudden diseases and visits from strange men in the middle of the night. Every so often, he’ll go through a stretch of time, moving from place to place, when he feels he’s being followed, watched. His heart jumps every time the phone rings. He knows people are not who they seem, are more than they appear. He’s failed because he was, and is, afraid.

But one day he did tell a writer the story of his last night with Lee.

They were to dock in Le Havre the next morning, and Joe Bill was trying to iron his shirts. He wasn’t good at it—his mother had always taken care of that. And after watching him struggle with the task for a while, Lee stood up from the desk where he was now openly practicing his Russian and took the iron from Joe Bill. After a moment or two, he said, “I’m going to spend a couple days in France, and I need to know how to say something.”

Joe Bill figured he’d tell Lee how to ask for the bathroom or the restaurant, figured he’d also tell him that most people in France spoke English, especially the service workers, but Lee said to him, as he pulled a sleeve taut and moved the iron across it, “Tell me how to say, ‘I don’t understand.’”

“I don’t understand?”

“Yeah,” Lee said.

“You want to know how to say, ‘I don’t understand’?”

“Would you just tell me?” Lee said as he folded Joe Bill’s shirt and set it neatly in the open suitcase, before taking up another and stretching it across the board.

“‘I don’t understand’ is ‘Je ne comprend pas,’” Joe Bill said.

“Juh nuh comprenduh pas?”

“Je ne comprend pas.”

“Je ne comprend pas?”

“Je ne comprend pas.”