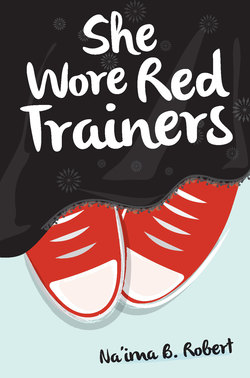

Читать книгу She Wore Red Trainers - Na'ima B. Robert - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление8

The tension in the house was too much for me. What with Mum on anti-depressants and the kids bouncing off the walls, I was just about holding it together. I had really wanted to continue working on my secret drawing of Mr Light Eyes’ hands but the kids didn’t give me any space at all. Between breaking up their squabbles, making their lunch and keeping the house from becoming a tip, I had to deal with Malik who had been clingy all afternoon, crying whenever Taymeeyah teased him. Even Abdullah was on edge. He kept tugging at my sleeve and signing, ‘What’s wrong with Mum?’ I found it really hard to reassure him when Mum had basically retreated to her room and refused to talk to anyone, let alone sign with Abdullah to let him know that she just needed a bit of space.

That was when I decided to set them all up at the table with some paints and paper. That kept Taymeeyah and Malik busy for about thirty minutes but it was better than nothing. By that time, Zayd was back from his Saturday job and I was like, ‘Bro, you need to take over. I need to get out of here.’ But then I noticed that Abdullah was still at the table, hunched over his paper, totally engrossed. I stepped up behind him to take a look and gasped with surprise. Abdullah had painted a figure in a box surrounded by angry black and red swirls. All around the box were words like ‘tired’, ‘scared’, ‘Mum’ and ’tears’.

‘Abdullah,’ I called out, touching his shoulder. Immediately, he shielded the paper with his arm but I gently moved it away. ‘What does the picture mean, babe?’ I asked.

He shrugged. ‘Means what it says,’ he signed.

And that was when I got the idea to introduce Abdullah to my world, the world of art as an escape. You don’t need to be able to hear to be able to appreciate beauty, or know how to use a box of paints.

I would start in the morning.

But first, I had to save what little sanity I had left: I had to get out of there and Rania’s house was just where I wanted to be when things got too hectic at home.

We had developed a Saturday ritual over the previous six months: Taymeeyah and I would go over to Rania’s house to escape the boys for the night. In the run-up to the exams, Rania and I had studied while the younger girls played, but now that school was over, we spent the evening talking, eating, doing henna and cackling over silly YouTube videos. Occasionally, we would listen to an Islamic talk. But with the Urban Muslim Princess event just a few weeks away, Rania had me working on her fashion show: the backdrop was my main responsibility, but I was also meant to be both Creative Director and one of the models on the catwalk.

‘And to think,’ I grumbled, ‘you’re getting all these services for free, all because you’re my best friend.’

Rania snorted. ‘Girl, please, you know you love it! And one day, when my brand is famous and I’m flying you to Dubai for my latest show, you’ll be able to say, “I was there when it all began.”’

I pulled a face. ‘Yeah, yeah, keep saying that while you treat me like a slave.’

Then we both laughed and went back to picking the accessories we wanted for each outfit in the show.

‘I wish my dad was here to see this.’ Rania’s voice was low and I could tell that this was something that had been playing on her mind for a while. She always missed her dad when things were going well, like when she had played Lady Macbeth in the school play, or the time her design was chosen for the new school sports kit.

‘He would have been so happy,’ she always said. ‘He always told me I could do anything.’

A lump in my throat appeared at that moment, just before the tears pricked my eyes. I didn’t know what that felt like: having a father who not only stuck around and played the role of ‘Dad’, but encouraged me to achieve my potential, and who was my biggest fan. Rania was so blessed. Really, she was.

Then Rania looked up at me. ‘What about your stepdad? Is he still troubling you?’

I had confided in her about Abu Malik months ago. Now I told her how he had left the house and that my mum was in her waiting period – the iddah – before the divorce would be finalised.

She heaved a huge sigh and hugged me. ‘Do you think that’s it then?’

I shrugged and did my very best ‘I-don’t-care’ fake out. ‘Hey, what can I say? Let the merry-go-round begin. It’s only Round Two, remember? A lot can happen in three months so he could be back again.’

‘Don’t, Ams,’ Rania said, and my heart twisted at the sadness in her voice. ‘I hate it when you talk like that, all hard, as if you don’t care.’

I heaved a sigh. ‘Rani, I had to stop caring a long time ago. This isn’t the first time, remember? I’ve been through all this before, so many times I’ve lost count. Of course, I hate the upheaval, especially for the kids, but, to be honest, I sometimes wish there were no stepfathers on the scene at all. Just us. Then, at least, we could have some stability. My mum doesn’t handle the iddah well at all.’

Rania closed her eyes and shook her head. ‘It’s just too awful, Ams. I can’t even imagine it.’

‘Of course not, Rani,’ I said, suppressing the bitterness in my voice. ‘Your parents were happily married for 18 years, mashallah. You had your dad around. You don’t know what it’s like to have stepdads and divorces and waiting periods going on all around you since you were little. You’re not a victim of your mother’s chaotic love life, basically.’ I felt bad then. It wasn’t Mum’s fault, not really. She just didn’t pick husbands very well. Either that, or she was a magnet for losers, troublemakers and men who just didn’t know how to value her.

This wasn’t the first time Mum’s relationship had failed. She’d had my older brother Zayd when she was 17, and me three years later. Neither of our fathers had stuck around long enough to name us so we had spent our early years with my nan while Mum tried to finish school, get a hairdressing qualification, anything to get some money coming in and some independence.

But then she met Uncle Faisal. He was running a da’wah stall on Brixton High Street, telling passers-by about Islam. Mum had stopped to listen and had been moved by the message. She always told us that it was the purity of Islam – the worship of one God, the clean lifestyle – that had first attracted her to the religion.

So she accepted Islam and Uncle Faisal asked her to marry him, told her he would provide for her and her kids, honour her as his wife. That was more than anyone else had ever offered her. That was how we ended up together in a flat in Stockwell, a family at last. Those were happy years, mashallah. Zayd and I loved Uncle Faisal like a real dad and he treated us just like his own kids, Taymeeyah and Abdullah.

But that marriage had had its fair share of ups and downs, false starts and separations. Then, one day, Mum told us Uncle Faisal was gone and wouldn’t be coming back. That was the beginning of the end of my illusions about life and love. I had been Uncle Faisal’s princess. Then he was gone.

Mum had married two more times after that – no kids, polygamy each time – before she met Abu Malik. I think she’d hoped that Malik’s dad would be the one, the one who would stay, the one she would grow old with as his only wife, who would do the right thing and raise his boy. But even I could see that he wasn’t the type to stick around and take care of his responsibilities.

When he left that first time, taking his box of Sahih Muslim and smelly football boots with him, Mum couldn’t handle it. She had just seen what she thought was the failure of her fourth Islamic marriage and it was all too much for her.

That was the start of the dark days of her depression.

That was the day I decided that I would never put myself in that position, not for a million pounds.