Читать книгу Father Luke’s Journey into Darkness - Nancy Carol James - Страница 6

Foreword

ОглавлениеThe sex abuse scandal of the Roman Catholic Church is a tragedy for all concerned. Nobody has derived benefit from it, because everybody is diminished. Even those who claim enmity with the Roman Catholic Church must forgo Schadenfreude—gloating over the misfortune of others—because nobody can honestly hold him or herself apart, as if, “This has nothing to do with me.” Such a statement is untrue and self-deceptive. Other ecclesiastical bodies—Protestant, Orthodox, independent—would be naïve to try to place themselves above the scandal or to rejoice in the suffering of the Church of Rome, because the issue touches all churches. One reason this is true is that people outside Christendom do not scrutinize the details of the crisis long enough to pinpoint the responsibility. No, blame is spread wide, because many people paint communities of faith in one broad swath.

John Donne declared, “No [one] is an island entire of itself; every [one] is a piece of the continent; a part of the main . . .” What diminishes one diminishes all. Many people are furious at the entire church universal because of the issue of sexual abuse. Two examples will bear this out: It was recently reported that priests in England are frequently insulted by strangers in public, based on nothing other than the wearing of a clerical collar. Two causes of this behavior can be cited: the increasing secularization of the culture, and the scandal of sexual impropriety, especially that involving minors. The second example is that of a clergy friend who, while riding an elevator with one other passenger, was shocked when that person suddenly spat on him, calling him a pedophile. Never mind that the clerical collar he was wearing was Anglican in style, not Catholic. To his angry assailant, the difference was negligible. One collared cleric was no better than another; all were equally stained.

Of course, sexual abuse by clergy, while widespread in the Catholic Church, is not limited to that denomination. In Canada, whole dioceses have gone broke because of financial settlements to the families of First Nation children, who, having been placed in institutions, were abused by Anglican clergy. Even Southern Baptists, who preach such stringent moral rectitude, have been marred by clergy sex abuse.

Crimes involving children, however, seem to evoke the greater wrath of society, and no wonder. While abused adults often have some recourse or some means of defense, children usually do not, and so are especially vulnerable.

What causes adults to assume that harming children—whether sexually or otherwise—is tolerable? What creates an environment that provides opportunity for such behavior? What causes the adult psyche to rationalize sexual abuse? What allows clergy—shamans of their culture, who in many instances are beloved for their otherwise beneficent, sacrificial acts of kindness—to undergo such a Jekyll and Hyde transformation? Such questions must be addressed with serious clinical inquiry and not through hasty speculation.

In the meantime, the public’s primary impetus is for control, not for clearer understanding. Society wants the behavior stopped, then understood, not the other way around. In addition, the lives of those abused need to be rescued, the damage addressed, and the wounds healed, so that something approaching a normal life is achievable. As for the perpetrators, the culture cries out for immediate cessation of the abuse and for punishment. The outcry is for emergency triage more than for systemic change.

That instinct is totally understandable. But what next? How is abuse stopped? How would systemic change look? How do we cure the underlying causes of sexually abusive behavior? How can the environment be changed so that opportunity for abuse is denied? And then, though little sympathy is left for them at the end of the day, what happens to the lives of the perpetrators once intervention has halted their behavior? Is there any redemption for them? These are questions that beg long-range solutions.

What about the condition of celibacy? No doubt some people, called to such a state for religious reasons, are able to fulfill their vows. But for others, celibacy is demanded of them in order to earn the right to practice the vocation to which they are called. Celibacy in these cases is not a vow taken willingly or joyfully, but a behavior imposed upon them. Does this create a burden that provokes errant behavior? Laying aside genital expressions of sexuality, what are the broader needs for human warmth and companionship? Are physical acts of tenderness and compassion, expressions of love, needed for health and happiness?

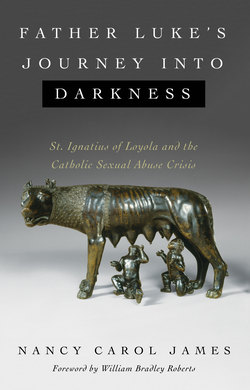

These are some of the complex issues raised by Nancy Carol James’s gripping novel, Father Luke’s Journey Into Darkness. Previously, the Rev. Dr. James has handled the genre of memoir (Standing in the Whirlwind) and numerous works of theology, biography, and biblical studies (various studies of, and translations of the writings of Madame Jeanne Guyon, the seventeenth/eighteenth-century French mystic). Now showing herself to be a skilled storyteller, Dr. James delves into the sensitive and controversial area of clergy abuse. In her capable hands, fiction is shown to be an effective way to approach some of the complex questions raised above. Caught up in the drama of her story, we are impelled to deal with the issues not so much in scientific, clinical ways (as important as those are), but in the manner they present themselves in the actual world: as events that shape and direct the lives of real people.

The Rev. William Bradley Roberts, DMA

Virginia Theological Seminary (Episcopal)

Alexandria, Virginia.