Читать книгу Early Warming - Nancy Lord - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Among the visuals that accompany reports and projections of global warming, there’s typically a map of the world that uses color to indicate temperature change.1 Blue stands for cooler than the mean for a given time period, yellow and orange for hotter. The reddest bands circle the high northern latitudes, and at least on the NASA map showing trends since 1955, the hottest spot of all lies like congealed blood over Alaska and the Canadian Northwest. This is where I live and where, like others from the north, I’m acutely aware of environmental change that has killed most of the spruce trees in my part of Alaska, eroded shorelines, and shifted our fisheries into different species and ranges.

Globally, surface air temperatures have increased by a bit more than one degree Fahrenheit in the last hundred years. A measly one degree, and yet, already, the climate disruption that’s resulted from that warming has been profound. Climate, it helps to remember, is the pattern of weather—encompassing averages, extremes, timing, and spatial distributions of temperatures, precipitation, and “events” like blizzards and tornadoes. Climate change refers to altered patterns. A small change in global average temperature (an index or indicator of the state of the global climate) can mean large changes in the patterns.

In Alaska and other parts of the north, average temperatures have increased rapidly and dramatically. Just in the last fifty years, Alaska temperatures averaged across the state and through the year have risen by 3.4 degrees Fahrenheit. Winter temperatures have risen more sharply, by an average of 6.3 degrees. Temperature increases have varied by community.2 My community—Homer, Alaska—has seen its year-round temperature increase by 3.1 degrees and its winter snows turn to rain. In February of 2010 even the slush melted away, moose knelt in our yards to eat green grass, and my neighbors and I went about without jackets or hats in sunny warmth as temperatures shot toward fifty. Then in March a blizzard dumped four feet of snow, temperatures dropped to zero, and schools were closed for the first time in decades.

“Polar amplification,” the science phrase for the tendency of temperature change to increase with latitude, depends on a number of factors, some of which are not yet well understood.3 The main process at work is the “ice-albedo positive feedback,” which simply means that when ice and snow melt, the darker land and water surfaces absorb more solar heat, causing more ice and snow to melt. More open water allows for strong heat transfers from the ocean to the atmosphere.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expects that climate change in the Arctic will be among the largest and most rapid on earth, with wide-ranging physical, ecological, sociological, and economic effects. Its fourth assessment, in 2007, noted that the polar regions are “extremely vulnerable to current and projected climate change,” of considerable geopolitical and economic importance, and are “the regions with the greatest potential to affect global climate and thus human populations and biodiversity.”

In other words, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. The polar regions function as the cooling system for our planet. As the climate and environment of the north change, so will the climate and ocean systems that regulate the entire world. The Kansas farmer and Florida vacationer don’t need to care about desperately swimming polar bears or Inupiaq hunters falling through ice to be concerned about what’s happening at the top of the world.

In the north, we live with disappearing sea ice, melting glaciers, thawing permafrost, drying wetlands, dying trees and changing landscapes, unusual animal sightings, and strange weather events. We live with such change, and we respond to it, through the myriad of daily choices we make about when and how to travel, what to plant in a garden or when to hunt or harvest, where to build, or how much to invest in a business like salmon fishing or snowplowing. Communities pull together to work on erosion control, wildfire prevention, and water supplies; some, like my town, have adopted (if not fully embraced and implemented) climate action plans.4 Our universities and other institutions support research and publish information they hope will be useful at all levels, including that of policy making. Governments respond—slowly, hampered by bureaucracy and the political strength of certain industries and skeptics.

Deborah Williams, a former Department of the Interior official and passionate conservationist, has been called “Alaska’s Al Gore.” One day in 2008 in the Anchorage office of the organization she founded, Alaska Conservation Solutions, she gave me what amounts to her “stump speech.” Alaskans are seeing the effects of global warming sooner than the rest of the world and “as witnesses have a moral responsibility to talk about what we’re seeing, the cause of what we’re seeing, and the imperative need to act.” Alaska, she said, should not just be the poster child for global warming but set an example by reducing its own carbon footprint. Alaskans can show what it takes to be both resilient and transformative. We’re first, in consequences and opportunity.

Two years later, in early 2010, President Obama’s secretary of interior Ken Salazar announced the selection of the University of Alaska as home to the first of eight planned regional climate science centers in the nation. He said this: “With rapidly melting Arctic sea ice and permafrost, and threats to the survival of Native Alaskan coastal communities, Alaska is ground zero for climate change. We must put science to work to help us adjust to the impacts of climate change on Alaska’s resources and peoples.”

Yes, there is a great variability, as the scientists say, to weather and climate, and the earth’s interconnected systems are immensely complex. None of us can say that a particular event is solely attributable to global warming. The trends, however, are clear, and the changes occurring in the north have been well documented by the IPCC in its series of reports, the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, ongoing scientific studies, and the popular press.

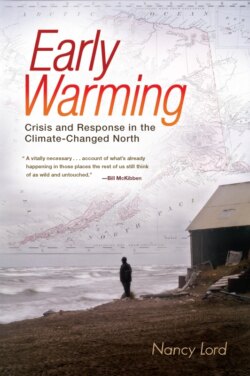

This book is not about the fact that climate change is occurring on regional and global scales (faster than the models predicted), that the emission of greenhouse gases from human activities (rising at an increasing rate) is driving it, or that we may be reaching “tipping points” after which the earth will likely be a very different and less hospitable place than that which has supported the human species since its members first learned to rub two sticks together.5 Although many people have chosen to ignore and even deny the peril we’ve brought upon our world, the scientific community has been in agreement for many years about the basics and seriousness of global warming, and publications on the subject abound.6 Some of them are listed in my bibliography.

This book, instead, takes a look at my reddish corner of the world and the ways that its people and communities are learning from, struggling and coping with, and adapting to the climate-related changes they encounter on a daily basis.

Of course, there’s a lot of change going on in the north besides climate. There’s environmental change brought on by resource development, land use, and the accumulation of toxins, and there’s continuing socioeconomic change. Native peoples in particular have leaped, in just decades, from traditional to modern lives. Changes related to global warming aren’t easily teased out of the entire fabric of change, and climate change isn’t usually the first thing that northerners—who face so many other challenges, from cultural loss to high energy costs and competition over resources—worry about.

Still, northerners live in and depend on the environment in more intimate ways than most Americans and tend to be keen observers. The indigenous among us, with ancestors who survived and thrived in a harsh and unforgiving climate for thousands of years, hold a particularly close and generational knowledge of their home places. These Native people, whose values are grounded in respect for the land and in cooperation, have in the past demonstrated great resilience and innovation.

An ecologist who has worked among northern communities for many years said to me, “These people are really good at adapting—and proud of their abilities. They’re not sitting ducks getting washed out to sea.” Their adaptation to date has been assisted by such things as strong community networks, an acceptance of uncertainty, flexibility in resource use, and government support.

And yet, the ability of individuals and communities to adapt, today, is constrained by political decisions made (or neglected) at every level—regional, national, and international. It’s also challenged by the unprecedented speed and degree of environmental change.

I have on my desk a brittle and yellowing scrap of newsprint I tore from somewhere a few years ago. The one paragraph reads, “‘We basically have three choices: mitigation, adaptation, and suffering,’ said John Holdren, the president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and an energy and climate expert at Harvard. ‘We’re going to do some of each. The question is what the mix is going to be. The more mitigation we do, the less adaptation will be required and the less suffering there will be.’”

Holdren is now President Obama’s science adviser. In testimony to Congress in July 2009, Holdren again pointed out the need to reduce carbon emissions and sequester as much carbon as possible and to make parallel efforts in adaptation. Adaptation strategies—such things as improving the efficiency of water use, managing coastal development with sea level rise in mind, and breeding drought-resistant crops—need, he said, to be employed at every level from the individual on up. This commitment, he said, would take leadership, coordination, and funding.

Until a few years ago, “adaptation” as related to climate change was rejected by many of us, from Al Gore on down, who were concerned it diverted attention from the critical need to reduce carbon emissions. “If temperatures increase, if sea ice decreases, we’ll just adapt,” was a toss-off response from those who wanted to continue business as usual. They posed adaptation as a simple solution, on the order of providing more air conditioners and, more positively in their view, taking advantage of ice-free Arctic waters for shipping and oil production.

Alaska’s representative Don Young, who at every opportunity mentions “the myth of global warming,” likes to talk about adaptation. He has opposed an endangered species listing for the polar bear and insisted that the bears can just switch from living on ice to living on land. He complained on a radio show, “We’re the only ones that are not adapting to climate change. We’re the only ones. All the other species will adapt. They’ll all change, and they will survive.”7 Rep. Young is apparently unaware that the current rate of species extinction is one thousand to ten thousand times faster than at any time in the last sixty-five million years, or that there’s a distinction between the common use of the word adapt (to adjust) and the biological one (in which species genetically evolve over time, through natural selection, to improve their conditions in relationship to their environments).8 The IPCC has estimated that global temperature increases in the next hundred years may match those that occurred over five thousand years at the end of the last ice age—a rate far too rapid for evolutionary change by all but the fastest-breeding (think fruit flies) species.9

The mitigation part of Holdren’s triad clearly isn’t going too well, as global emissions continue to rise and the international community fails to brake a disastrous course. Adaptation—as in making human choices about how we’ll live with the changes already set in motion by global warming—is now taking over much of the discussion, as it must. Even then, it’s important to realize that adaptation as Holdren and others intend it involves proactive planning for the long-term—making changes to activities, rules, institutions, and so on in order to minimize risk. It is not the same as coping, which is a short-term response to protect, right now, resources or livelihoods. Coping mechanisms can get you through an event or year but can easily be overwhelmed.

Lara Hansen, an ecologist who started a nonprofit called EcoAdapt, lamented to me as I began this book the lack of a “field” of adaptation.10 (This has been described elsewhere as an “adaptation deficit”—the difference between what we know and what we need to know to help with adaptation. This gap exists both in scientific research and in policy making.) Resource managers, community planners, and others working in areas affected by climate change, Hansen told me, “know at some level they need to work on this, but they feel completely disempowered to do anything because they’ve never had any formal training on what adaptation is. Generally when I talk to people at state agencies, the response I get is, ‘Yeah, we know we need to be doing something about this, but we don’t know what it is, and we don’t even know how to start approaching it.’ There’s very little in the world to help a person define a good adaptation versus a bad one, or to decide what is effective and fiscally wise or not.” Hansen founded EcoAdapt to train people in what she called “unfortunately a growth industry.”

The north, Hansen said, is a very useful place from which to learn. “The changes are happening so fast that the people and ecosystems have already started to do things. It’s not been formally called adaptation, but it’s happening. We need to know what those things are and try to learn lessons from them. What’s working? How did people come up with the ideas of what they thought would work? What kinds of decision-making processes generated successful responses? What kinds of partnerships helped? How can we facilitate the kinds of conversations that need to happen? And how can we use those experiences to empower vulnerable communities in other parts of the country or world as they deal with their unique responses to climate change? How do we build the network so that people in analogous situations talk to each other and share what they’ve learned—and do it in a manner that works for them?”

Hansen had found most of the guides dealing with climate change adaptation to be written in language that was incomprehensible or alienating to ordinary people and “wildly inappropriate to deal with the problem at the level that it needs to be dealt with. It’s not a problem that’s going to be dealt with by individuals sitting in high government offices.”

What will adaptation in the north look like? One thing we pretty well understand—it will be expensive. A study by the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Alaska estimated that the changing climate will make it between 10 and 20 percent more expensive to build and maintain public infrastructure in Alaska over the next couple of decades.11 These additional costs (billions of dollars) are mostly associated with the effects on roads, runways, and water systems of thawing permafrost, erosion, and flooding. Analyses show generally, though, that the costs and difficulties of adapting will be much greater if action is delayed. Other adaptation strategies that have been discussed include things like more flexible and more conservative management of fish and wildlife resources, protection of key lands and waters, technological assistance, and training for new jobs. Adaptation, for some living in coastal areas, will also involve building seawalls and/or moving to higher ground.

In a perfect world, climate change adaptation in the north might be integrated into broader objectives to solve additional social, economic, and cultural problems while acting as a proving ground for particular strategies.

One way or another, the early-warming north will be a proving ground. The north is where we’ll find out just how creative and responsible humans can be. Maybe, we’ll show how to turn a crisis into stronger communities and a more sustainable future. Or maybe the lessons will be quite different; maybe what we’ll learn is how hard it is to lose homes and livelihoods, the costs of ignoring risk and peril, what it means to suffer.

My homeplace, Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula, depends for its life on salmon. Salmon have fed people here since the first Pacific Eskimos showed up, salmon kept the early homesteaders going, and salmon today support families engaged in commercial and sport fishing. For twenty-five years I fished commercially for salmon in Cook Inlet, and I love this place in all its weathers and sea conditions but especially in its bounty. The nutrients that spawning salmon deliver upstream feed bears, birds, other fish, plants, the entire ecosystem. To the degree that climate change alters rainfall, evaporation rates, plant cover, stream temperatures, and ocean conditions, salmon may find themselves living in an environment quite different than in the past. Or not living—not surviving, at least not as well or in the same places as they do now.

I set out, first, to learn in my own neighborhood about streams and salmon. I wanted to know what was happening relative to climate, and I wanted to understand how science—so much of it scaled globally and so bound in scientific conservatism and jargon—could be explained and made useful on a local level. I would start at home, and then I would head northward, to see how people elsewhere were responding to their own climate change challenges. My inquiry would be, by necessity, more opportunistic than comprehensive—based on visits to a scattering of communities, with their disturbing climate news and the occasional example of promising innovation. I wanted to see if people in the forefront of so much change were getting information and the assistance they needed, and how their expertise was informing others. Even as I knew that in North America—with our collective wealth and privilege—we have so many more options than most of the planet’s people, I wanted to catch a glimpse of what the future might hold for us all, the world over.