Читать книгу The Jerrie Mock Story - Nancy Roe Pimm - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеFLIGHT ONE

MARCH 19, 1964

NO ONE would ever have believed that Jerrie Mock had a big day ahead of her. The thirty-eight-year-old woman straightened the house, packed a suitcase, and ran some errands. According to the Columbus Dispatch, “The petite Bexley housewife and mother went matter-of-factly about her business on the day before, and, like any woman about to take a trip, she had an appointment at the beauty parlor.”1 The next day she would leave to fly around the world. In 1964, there were very few female pilots, and even fewer who dared to fly alone for such a long distance. As Jerrie Mock planned her flight, she discovered that, if she succeeded, she would be the first woman to circle the globe, solo.

When the big day arrived, she finished packing her cramped little airplane, a Cessna 180 she had lovingly nicknamed Charlie. Three of the four seats had been removed, replaced with aluminum gas tanks, converting the single-engine airplane into a long-distance marathon flier. She squeezed a typewriter onto the pile of maps, a variety of snacks, her suitcase, an oxygen tank, and a bulky life raft. Jerrie planned to write all about her journey and send her reports back to the local newspaper.

THE CUSTOM-MADE FUEL TANK DESIGNED BY DAVE BLANTON BEFORE INSTALLATION INTO CHARLIE

Courtesy of Phoenix Graphix

DIAGRAM OF 1953 CESSNA 180

Jerrie’s husband, Russ, and their two teenaged sons helped her fill the plane with emergency equipment and supplies. Their three-year-old daughter, Valerie, stayed at home with a neighbor because a big crowd was expected. Throngs of people swarmed around the tiny plane at the airport in Columbus, Ohio, in hopes of witnessing history. One reporter shoved the microphone at Jerrie and said, “Mrs. Mock, aren’t you a little afraid? After all, no woman has ever done this.”2

“Mrs. Mock, what do you think happened to Amelia Earhart? Do you think she’s still alive somewhere?”3

Jerrie thought of her childhood hero, Amelia Earhart. Amelia had flown in races and set records. But there was one record she had wanted more than any other—to fly around the middle of the globe, the equator. On May 21, 1937, Amelia Earhart made her second attempt at the world record. Near the end of her trip, on July 2, 1937, she flew out of a small airport in Lae, Papua New Guinea. Earhart disappeared, never to be seen again. What had happened to the pilot is still a mystery to this day.

Jerrie needed to concentrate and keep things such as fear and disappearances out of her mind. She couldn’t be bothered with all the questions. She had a plane to fly. Jerrie mentally went through her checklists. After all, she had a job ahead of her, and the reporters made her more nervous than the idea of flying over deserts and oceans. They persisted with their questions. Jerrie gave short answers as she stood by her plane in front of Lane Aviation, posing for one photo after another. She trembled with fright, suddenly realizing the enormity of what she was about to attempt. She smiled bravely, and kept her fear hidden. After all, people were counting on her.

The Columbus Evening Dispatch, her local newspaper, had promised its readers that she would “keep a careful record of her flight and her personal impressions.”4 A former Air Force pilot, Brigadier General Dick Lassiter, had met with Jerrie many times, helping her plot the best course to take around the globe, country by country. Major Art Weiner, also with the United States Air Force, had spent countless hours preparing navigation maps, checking weather forecasts, and making flight plans. And, last but not least, her family supported Jerrie in her quest to follow her childhood dream.

JERRIE POINTS OUT THE ROUTE SHE PLANS TO FLY, AS HER HUSBAND, RUSSELL, AND THREE CHILDREN, VALERIE, GARY, AND ROGER, LOOK ON

Reprinted with permission from the Columbus Dispatch

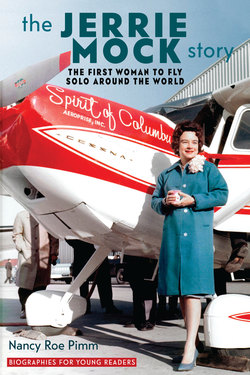

Jerrie took comfort standing beside her eleven-year-old airplane while the photographers’ flashbulbs popped. She wore a white shirt and a blue knit skirt under her blue coat, with high heels on her feet and pearls around her neck. Charlie sported a brand new red-and-white paint job with the words Spirit of Columbus emblazoned on its nose. She knew the single-engine Cessna was the best plane for such a flight. Charlie was tried and true, capable of flying around the world. One of the reasons she had chosen a Cessna 180 was because she had been told that with its high-set wings and powerful engine “a 180 could take off with anything you could close the door on.”5 As Jerrie made plans to fly around the world, she prayed. She had said, “I gradually felt certain that God wanted me to make the trip and would see that I got home safely.”6 And now her dream was becoming a reality. How could she turn back?

JERRIE STUDIES WEATHER MAPS AND HER LOGBOOK AS SHE PLANS HER ROUTE AROUND THE WORLD WITH HER JEPPESEN FLIGHT COMPUTER IN HAND

Susan Reid collection

Russ came to Jerrie’s side and steered her to their car. She needed to go to the weather bureau and the flight service station in the nearby Port Columbus terminal building to make a final check on the weather conditions and fill out an international flight plan. For official record purposes, there would be observers and timers at each stop to document every takeoff and landing for the NAA, the National Aeronautical Association, and the FAI, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Howard Kenny, the head weather forecaster at Port Columbus, assured her that the weather looked good all the way to Bermuda. Once in the office of the flight service station, Jerrie was instructed to mark down her survival equipment. She completed the form, relieved that no one seemed to notice her trembling hand.

. . .

LUCKY LINDY & LADY LINDY

JERRIE MOCK named her airplane Spirit of Columbus after Charles Lindbergh’s historic airplane, Spirit of St. Louis. Charles Lindbergh, “Lucky Lindy,” became a national hero when he flew the Spirit of St. Louis nonstop from New York to Paris. His historic flight in 1927 took over thirty-three hours. At times he felt like he was asleep with his eyes open! In order to stay awake, he opened the window and let the frigid air cool off his face. When asked why his cat, Patsy, did not accompany him like she usually did, he said, “It’s too dangerous a journey to risk the cat’s life.”7

Amelia Earhart was called “Lady Lindy” by the press due to her uncanny resemblance to Lindbergh. Amelia had once said, “The most difficult thing is the decision to act; the rest is merely tenacity.” She flew over the Atlantic Ocean on June 3, 1928, accompanied by Bill Stultz and Lou “Slim” Gordon. Word spread, and thousands came to greet the first woman to fly over the Atlantic. When Amelia made her around-the-world attempt in 1937, she was accompanied by navigator Fred Noonan. Amelia decided to lighten her load when they were about to begin their long cross-ocean flight to Howland Island. She boxed up and sent home everything she didn’t need for the flight, even her lucky elephant-toe bracelet. “There must not be a spare ounce of weight left,” she said.8 The only exception she made was for the five thousand souvenir stamp covers kept in the nose cargo hold of her plane. She planned to sell the autographed envelopes to help fund her trip around the world. Sadly, Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan disappeared, never to be seen again.

. . .

When all the necessary forms were filled out, Russ hurried Jerrie back to the Cessna, back to the crowds. Jerrie only wished to be alone in her plane, tucked away from the reporters, the microphones, and the endless questions. After all, she had a seven-hour flight ahead of her to the island of Bermuda, and she wanted to get going before her nerves got the best of her.

As soon as Russ opened the car door, the reporters hounded Jerrie with questions. She grew more annoyed with each one. As the cameras clicked, she hurried to the side of her plane and smiled bravely beside Governor James Rhodes of Ohio. Flashbulbs nearly blinded her as more photos were taken with Preston Wolfe, the publisher of the local newspaper. She posed with the wives of astronauts John Glenn and Scott Carpenter. An old friend nudged Jerrie and gave her a Bible to take along.

Jerrie’s family gathered around. Her mom fretted. She had never understood Jerrie’s adventuresome spirit, and she had always wished her daughter had an interest in something more down to earth, like knitting. Her sister Susan squeezed past a tall newsman and handed Jerrie a cup of hot coffee, while her sister Barb reminded her to collect stamps at every stop for her collection. Her dad told her to be cautious, and he promised to pray for her safe return. Jerrie’s mother-in-law, Sophie, clasped a St. Christopher medal (the patron saint of safe travels) to Jerrie’s coat and vowed to watch over her family.

Dave Blanton, who had developed the plane’s fuel-tank system, gave her some last minute advice. He showed her how to put rags around the opening when filling up the airplane to keep the gas from leaking into the cockpit. He stressed the need for plenty of rags, fresh rags at every stop.

JERRIE POSES WITH HER MOTHER, BLANCHE WRIGHT FREDRITZ, AND HER FATHER, TIMOTHY FREDRITZ

Reprinted with permission from the Columbus Dispatch

JERRIE’S HISTORIC FLIGHT MAKES FRONT-PAGE HEADLINES IN THE COLUMBUS EVENING DISPATCH

Reprinted with permission from the Columbus Dispatch

After all the preparations were complete, Jerrie removed her coat to let Blanton and Russ place the cumbersome life jacket around her. The well-wishers and reporters seemed to inch closer and closer. Jerrie stood silently, but her insides shook. Blanton buckled the straps of the life jacket while Russ walked around the airplane to make one final inspection. Wearing a large straw hat, Jerrie climbed the high step to the cockpit. She adjusted the two pillows behind her back and the one underneath. Being only five feet tall, she needed the pillows to help her see out the windshield.

When Jerrie was finally nestled in behind the controls in the peaceful cocoon of Charlie, Russ leaned into the cockpit. After giving her a kiss, he reminded her to take plenty of notes so she would have lots of good stories for the newspaper. Jerrie nodded and glanced over at her two sons. They looked worried. Were they afraid that they might never see their mom again? She wished she could get out of her plane and give them one last hug.

JERRIE WITH DAUGHTER, VALERIE, AND HUSBAND, RUSS

Reprinted with permission from the Columbus Dispatch

Her head swirled from all the commotion, making it difficult to concentrate on her checklist. Jerrie reached for the master switch and the starter button on the left side of the panel. The engine rumbled as the propellers sliced through the air. Jerrie trembled with fear, wondering if she should call the whole thing off and rush back to her family. But she knew at this point going back wasn’t really an option. So she went through one last checklist and taxied down to the long runway. Jerrie got on the radio and let the controller know she was ready for takeoff. His voice came across the radio giving her clearance to go.

At 9:31 a.m., Jerrie Mock pointed the nose of her aircraft toward the end of the runway at Port Columbus. Alone in her plane, she took a deep breath, and pushed in the throttle. Charlie barreled down the airstrip. Fire trucks and cameramen were lined up along both sides of the runway as they rolled past. The roar of the powerful engine thrilled Jerrie as the aircraft’s wheels left the ground. The high-set wings of her plane lifted into the air and she trembled with excitement. Finally, after a lifetime of dreaming, she would see the world!

As the plane made its climb, heading east, Jerrie heard the tower controller say over the radio and the loudspeakers at the airport, “Well, I guess that’s the last we’ll hear from her.”9

Jerrie Mock couldn’t believe her ears. “I’ll be back,” she thought. “But I hope to never see him again.”10

DID YOU KNOW?

Before Wiley Post flew out of Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn, New York, and became the first man to fly solo around the world, he worked as a professional pilot. Businessmen paid Wiley to fly them to their destinations. The experienced pilot earned worldwide fame with his record-breaking flight in 1933, but he already had earned worldwide fame as a race pilot competing in air derbies.

Jerrie Mock was not a professional pilot when she took off to fly around the world. She earned her private pilot’s license in 1958, and six years later, with only about 750 hours of flying time behind her, she attempted her historic flight around the world. In order to fly around the world, she needed to get certification to fly her plane using instruments only. She became an instrument-rated pilot before she left the country, but she never had the chance to practice her new skill without an instructor sitting beside her before she left on her around-the-world flight.

Wiley Post was the first man and Jerrie Mock was the first woman to fly solo around the world. By coincidence, both of them also decided to elope when it came time to marry.