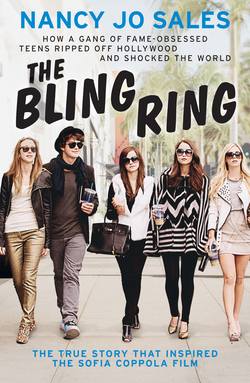

Читать книгу The Bling Ring: How a Gang of Fame-obsessed Teens Ripped off Hollywood and Shocked the World - Nancy Sales Jo - Страница 6

Оглавление

In the spring of 2010 I got a message from someone in Sofia Coppola’s office saying that Sofia was interested in optioning my Vanity Fair story, “The Suspects Wear Louboutins,” which had just run in that year’s Hollywood Issue. I was thrilled, but also wondered what in this story could possibly appeal to Sofia Coppola. It was about a teenage burglary ring that had targeted the homes of Young Hollywood between 2008 and 2009. The burglars, most of them recent high school graduates, had made off with nearly $3 million in designer clothing, jewelry, luggage and art from a collection of “stars” you wouldn’t exactly expect to see in a Sofia Coppola movie—Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, Audrina Patridge (one of the girls on the reality show The Hills), to name a few. They were famous mainly for being famous, defined by a new kind of celebrity that was all about Facebooking and tweeting and the flashing of thongs. Or maybe the Instagramming of thongs.

It was also a story about kids from an affluent suburb in the Valley—another factor that seemed to make it an unlikely subject for Sofia. She made beautiful-looking movies about beautiful places—she’d shot much of Marie Antoinette (2006) at Versailles, the only person ever allowed to film there—and this was a story about a tackier world where the rich were brash and bloated on their wealth … But then, that sounded a lot like the Ancien Regime before the French Revolution. And maybe the one percent in America today.

But when I started re-watching some of Sofia’s movies in anticipation of meeting her, I realized that the themes in the story of the “Bling Ring”—the name given to the burglary ring by the L.A. Times—were some of the same themes she had been exploring in her films: the obsession with celebrity; the entitlement of rich kids; the emptiness of fame as an aspiration or a way of life. Her first feature, The Virgin Suicides (1999), based on the novel by Jeffrey Eugenides, was about a family of rich girls in Gross Pointe, Michigan, who unaccountably all kill themselves, thereby becoming “famous” in their neighborhood. Sofia’s Marie Antoinette, played by Kirsten Dunst, was a spoiled teenager and a rock star in her own time (until, of course, she lost her head). Lost In Translation—for which Sofia won the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay in 2004—was a portrait of an action star (Bill Murray) drowning in a fishbowl of fame; and in Somewhere (2010), Stephen Dorff plays another famous actor living in the legendary Chateau Marmont hotel and finding his existence at the center of Hollywood lonely and meaningless. So, it seemed, the story of a gang of fame-obsessed teens that had robbed the homes of celebrities was to Sofia Coppola sort of like a good horror story was to Hitchcock.

It happened to be right up my alley too. When news of the Bling Ring burglaries first came out, a friend of mine joked that it was like a “Nancy Jo Sales story on speed.” I suppose I knew what he meant. I’d been writing about the misadventures of rich kids since 1996, when I did a story for New York magazine my editor headlined “Prep School Gangsters.” It chronicled the lives of private school students in New York as they acted out underworld fantasies based on gangsta rap and too many viewings of Goodfellas. It was entirely by accident that I got on this beat, which has led me to stories on clubkids and kid models and socialites and d.j.’s and rich kids in love. At the same time, I was doing celebrity profiles on some of the very people these fame-conscious kids wanted to be—Puffy and J-Lo and Tyra and Leo and Jay-Z and Angelina, as well as two of the Bling Ring’s famous victims, Hilton and Lohan. (I did the first magazine story on Hilton, for Vanity Fair, in 2000.)

• • •

I met Sofia for the first time at café in Soho, the Manhattan neighborhood where she was then living with her husband, Thomas Mars, the front man for the alternative French rock band Phoenix, and their daughter, Romy, then 3. Sofia was pregnant at the time with her second child (Cosima, who would be born in May 2010), and putting the finishing touches on Somewhere in the editing room. It was a warm, bright day, and Sofia, in a light purple cotton dress, looked very lovely, with her slanting brown eyes and creamy skin. She was soft-spoken and calm and had a dreamy quality about her which somehow reminded me of the delicate touch of her films. We sat at a table at the back of the restaurant and had breakfast, coffee for me, tea for her. I asked her what had interested her in the Bling Ring story, which she said she had read on an airplane returning to New York from L.A.

“I thought, somebody should make a movie of this,” she said, “and I thought probably someone already was. It never occurred to me that this was something that I would do. Then I kept going back to it—I think because it had in it all of these things that I’m worried about in our culture, or thinking about. I don’t know if ‘microcosm’ is the right word, but somehow it distills all the cultural anxiety of right now. I feel like this story kind of sums it all up.

“To me it’s the whole idea of the narcissism and the reality TV and the social media obsession of kids of this generation,” she said, “and the entitlement—that they,” the Bling Ring kids, “thought it was O.K. to just go into these homes and take whatever they wanted. I think all these themes are in this story and this was what I was connecting to without being aware of it at first. I think it’s about what our culture is all about right now—it’s just so different from when I was growing up….”

Sofia grew up in the Napa Valley, where her father, The Godfather (1972) director Francis Ford Coppola, moved her family from New York in the 70s. “I always knew that we got special attention and the attention was all about him,” she said, smiling, when I asked if she had realized as a child that her father was famous. “But we lived in Napa, which doesn’t have a lot of showbiz people, so we were like ‘the Hollywood people’ there. I feel like that must have had some influence on why I’m always drawn to this step-world, this meta-world” of people living with some kind of fame.

She was raised in a household full of celebrities who to her weren’t celebrities—they were just her family. Sofia wouldn’t be Sofia if she hadn’t grown up around filmmakers. Her mother, Eleanor Coppola, is a documentary filmmaker; her brother Roman is a screenwriter and filmmaker; her aunt Talia Shire and cousins Jason Schwartzman and Nicolas Cage are actors; and her grandfather, Carmine Coppola, was an Oscar-winning film composer. (Her older brother, Gio, a budding director, died in a speedboat accident in 1985.)

Her parents’ friends were filmmakers and writers, actors and artists. One of her earliest memories is sitting on Andy Warhol’s knee. Marlon Brando, Werner Herzog, Steven Spielberg, and George Lucas were all dinner guests at her family’s home. Her Italian father set the tone, which was warm and inclusive, so the kids were always around listening to the adults talking about filmmaking. “I think I was learning all these things sort of without knowing it,” Sofia said. And when she and her family would accompany her father on film shoots—they spent months in the Philippines during the filming of Apocalypse Now (1979)—she would watch filmmaking firsthand. (Her mother co-directed an unforgettable documentary about that experience, 1991’s Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, in which little Sofia appears.) “For me as a kid it was just about getting to take a helicopter ride over the jungle,” said Sofia.

In her teens she became fascinated with fashion; at 15, she worked as an intern for Chanel. “When I was a kid nobody had designer handbags,” she remembered. “In high school there wasn’t all this label awareness. It wasn’t as much of a mainstream culture thing back then. I remember going to fashion shows and you’d never see celebrities sitting in the front row. Now celebrities have clothing lines—and now Alexis [Neiers],” one of the Bling Ring burglars, “wants to be a fashion designer too.”

As did several other kids in the burglary ring. As I got to know Sofia, it struck me that as a teenager she had had some of the same aspirations as the Bling Ring kids—the difference being, of course, that she was the genuine article, the sort of It Girl they longed to become. After leaving the California Institute of the Arts, where she had studied photography and costume and fashion design, she started her own clothing line, Milkfed, which is still sold exclusively in Japan.

Over the almost three years between our first meeting and the completion of The Bling Ring, which premieres on June 14, 2013, Sofia and I would get together to talk about the movie she was writing and then directing. I always looked forward to seeing her. She was fun to talk to. It seemed we were always gossiping about Hollywood, as if something about the subject matter we were dealing with was turning us into the worst kind of tabloid junkies. We talked about the celebrification of everything, which seemed to have happened overnight, over roughly the last decade. I said I thought the milestone was the ascendance of Paris Hilton. Sofia said she thought it was the explosion of tabloid journalism.

“I think Us Weekly changed everything,” Sofia said, referring to how Us magazine went from a monthly to a weekly in 2000, becoming more gossipy and invasive and igniting a huge boom in the coverage of celebrities. “I remember living in L.A. before Us Weekly and you could go out and do things and have privacy,” she said. “I mean, I don’t feel like I’m really in that [celebrity] world, but suddenly it was different. There weren’t paparazzi around all the time before. And another big change was TMZ,” which launched in 2005. “I remember I went and lived in France for a few years and then I came back TMZ was everywhere and it was so weird. It happened fast, too, like TMZ and Twitter and reality TV all of a sudden were everything and it was like our culture just went crazy.

“With Twitter,” she said, “it’s insane how accessible these stars are”—so accessible that the kids in the Bling Ring “thought that they knew them because they knew what they were eating for breakfast. So they felt comfortable going in their homes.”

Sofia seemed to share my amazement for the way the kids in the story spoke about what they had done, as if they were already stars themselves—especially Alexis Neiers. Sofia had read the transcripts of my interviews with Alexis and some of the other Bling Ring defendants, some of the dialogue from which she said she was incorporating into her film. “When people [she was showing her script to] read it,” she said, “they’re like, oh my God, how did you come up with that? And I tell them that was real, that comes from the transcripts. I used the real stuff because I couldn’t make it up, it’s so absurd.”

In my Vanity Fair piece, for example, Alexis tells me how she thinks she might “lead a country” some day. Her comment wasn’t directly related to the burglaries—but perhaps it was. At 18, she was already convinced of the power of her pseudo-fame.

“It’s so weird to me today,” Sofia said, “this whole idea of being famous for nothing. I guess that started with the reality TV thing and then it became normal. The [Bling Ring] kids all wanted to be famous for no reason. When I was a kid people were famous because they accomplished something, they did something.

“I feel like such an old fogie complaining about all this,” she said, smiling self-consciously.

By February 2012, Sofia had cast Emma Watson in the role of Nicki, based on Alexis Neiers (who had now become a consultant on the film, which was becoming like an Escher woodcut about celebrity). “I met with [Emma] and she was so interested in playing the part,” Sofia said, “and I felt like she had a really smart take on it. She understood the themes because of her popularity.” As a co-star of eight Harry Potter films, Watson had an almost cult-like celebrity status. “She was very interested in the whole subject matter of celebrity,” said Sofia. “And she could relate to it, she knew exactly how things are for a celebrity today—she could see it both from the kids’ perspective, who were like, her fans, and from the people on the other side, the ones who were robbed.

“I forgot how famous she was,” Sofia said. “I had the kids” who had been cast in the movie, “all go out to lunch together one day, to bond, and they got swarmed with paparazzi.” Throughout The Bling Ring shoot, which took place in Calabasas, California, and L.A. in March and April of 2012, the set would be dogged by paparazzi and videorazzi and gossiped about on celebrity blogs such as TMZ, mirroring the very themes in the film.

In preparation for their roles, Sofia had also had the young cast—which includes Israel Broussard, Katie Chang, Claire Julien and Taissa Farmiga—“rob” a house in the Hollywood Hills. “It was an improv,” Sofia said. “Before we started filming we had them actually sneak into a friend of mine’s house” (not someone famous). “We set it up so that no one would be home and we had them break into the house while my friend was away for a few hours. We left a window open and we gave them things that they had to take from the house. We gave them a list.” The Bling Ring kids often went “shopping,” as they called their burglaries, armed with lists of articles of clothing owned by their famous victims, items which they had selected from research they did on the Internet. “They did great,” Sofia said of her cast. “They were very good burglars.”

Why did the Bling Ring do what they did? Why steal celebrities’ stuff? This was something Sofia and I talked about a lot. She said, “I love the quote” from the transcripts “in which Nick [Prugo] says,” of his co-defendant Rachel Lee, “ ‘she wanted to be part of the lifestyle, the lifestyle that we all sort of want.’ I thought it was so important to put that in the film, that he assumed that that we all want that lifestyle.”

Finally, Sofia and I talked about raising daughters in a culture gone mad for fame. She told me of how her daughter Romy, now 6, had recently informed a lady in the park that her mother was “famous in France.”

“I don’t even know how she knows that or why she thinks that’s important,” Sofia said, laughing. “I hope there’s going to be a reaction against all this,” that is, our cultural obsession with fame. “There has to be right?” she asked. “I’m hoping that when our kids are teenagers and young women it’s on the reaction side.”