Читать книгу Among Wolves - Nancy Wallace K. - Страница 11

CHAPTER 6 Revelations

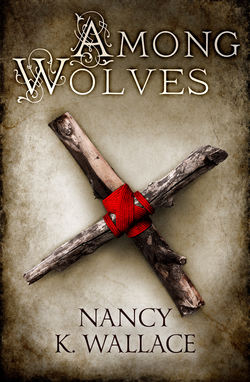

ОглавлениеGaspard chattered constantly during dinner. The clink of silverware provided a subtle counterpoint to his monologue. Despite his apparent good humor, Devin realized that the incident with the twine-wrapped cross had shaken Gaspard deeply. He simply wasn’t about to admit it to anyone.

They had no clue as to who had broken into Devin’s room. Gaspard and Marcus had entered the ship’s dining room just before Devin, and all the other passengers were present. So, it was impossible to tell who might have been responsible for placing the cross inside the itinerary. Obviously, whoever had done it, either had access to the Captain’s master key, or was a trained thief. No one they had met so far seemed a likely suspect, and Devin was tired of speculation. They’d sat for hours over the little folding table littered by fish bones piled on dirty dishes and greasy, discarded napkins. Devin and Gaspard had perched on the bunk, giving Marcus the only chair in the tiny cabin.

Gaspard lifted the wine bottle to refill Devin’s glass, but he covered it with his hand.

“I’ve had enough,” he muttered irritably, “and so have you.”

“Lighten up,” Gaspard demanded, topping off his own glass. “Why don’t we just forget about the whole thing? No one’s been hurt. It was probably just a childish prank. Someone is simply trying to scare you. If they’d intended to kill you, they could have laced the cross with poison. All you would have had to do was pick it up, and you’d be dead.”

“No, you’d be dead,” Marcus pointed out. “Devin had sense enough not to touch it when he was told not to.”

“So, I’d be dead,” Gaspard conceded. “But I’m not, so that proves my point.”

Devin grinned. “Maybe it’s a slow acting poison and tomorrow when I try to waken you…”

“Enough,” Marcus said. “This is a serious matter. That symbol represents both a warning and a threat.”

“How do you know that?” Devin asked. “I’ve never even seen one of those before.”

“My family has its roots in Sorrento,” Marcus answered. “Those curse symbols are common there. I remember my mother showing me one once. A disgruntled customer had left a blue one on someone’s stall at the market.”

“And people actually fear them?” Gaspard asked.

“Oh, yes,” Marcus said. “They are taken quite seriously. My grandmother used to tell the story of a man who was feuding with his neighbor. One morning he left a red cross in the middle of the road so that his neighbor would step on it when he took his vegetables to market. The neighbor packed up his donkey and started to town, never even seeing the cross lying in the road. The donkey stepped on it instead. That evening on the way home, the donkey tripped along the cliff road. It fell into the sea and drowned.”

Gaspard grimaced. “Shit, Dev, you owe me.”

“Apparently,” Devin agreed, his eyes on his bodyguard. “Marcus, were you raised in Sorrento?”

“No, I was born in Coreé.”

“And when did you decide to go into my father’s service?”

Marcus shrugged. “I don’t remember ever being given a choice. My family has served your family for generations both in Coreé and on your father’s estate in Bourgogne.”

“That’s hardly fair to you, is it?” Devin said.

“Your father has been good to me. Not only did he give me a responsible position in his household but he taught me to read and write.”

“He taught you himself?” Devin asked in astonishment.

Marcus nodded. “Every evening for several years.”

Devin laughed. “That surprises me. I wish I had known before.”

Gaspard savored another sip of wine. “Wasn’t he breaking the law by teaching you?”

“Gaspard,” Devin cautioned.

Marcus extended a placating hand. “It’s a legitimate question. Monsieur Roche said that my position as his bodyguard required me to carry correspondence, and it was necessary that I learn to read and write.”

“And yet, he didn’t sponsor you and send you to school which he could have done legally. He taught you himself,” Gaspard pointed out.

Marcus shrugged again. “I was already in his employ. He’s a good man. He treats his people with respect, both in Coreé and in Sorrento.”

“So, perhaps Henri LeBeau wasn’t so wrong in his assessment of Vincent Roché?” Gaspard remarked thoughtfully.

Devin glared at him. “So, you think my father was wrong to educate Marcus?”

Gaspard’s hand flew to his chest. “I didn’t say that! God, you’re touchy tonight! I am actually questioning LeBeau’s motives. I was wondering if someone had started a movement to discredit the Chancellor.”

Marcus was silent for a moment. “We had the first indications of that several months ago. Unfortunately, we suspect that your father may be one of the instigators.”

Gaspard rolled his eyes. “That’s hardly a surprise.”

“Why didn’t Father tell me?” Devin asked. The Chancellor Elite was elected by the Council. The position was normally held for a lifetime, as long as the candidate remained powerful and respected. Only twice in the past thousand years had a Chancellor been deposed by a political coup, and that had been in the early years of the empire.

“There was nothing you could have done,” Marcus replied.

“I could have stayed home.”

“And what would that have accomplished?” Marcus asked.

“My visit to the provinces wouldn’t have sparked controversy which put my father in a difficult position.”

“Well, now that your trip is underway, conduct yourself in a manner that won’t worsen the problem,” Marcus answered curtly.

“Obviously, it is already worse!” Devin said. “LeBeau is intent on starting rumors, and someone is trying hard to deter me from going.”

“But the Council’s objections and our little folk symbol seem to be at cross purposes,” Gaspard pointed out.

“What do you mean?” Devin asked.

Gaspard leaned back against the wall and drained his wine glass before answering. “It seems to me that this trip plays right into my father’s hands. Why would he try to discourage you from going, if he intends to use your visit to the provinces to discredit your father?” He fumbled for the bottle on the floor, only to find it empty.

“Maybe your father professes one view publicly and works privately to further the opposite position,” Devin said.

“Or perhaps there are two factions working independently,” Marcus suggested.

“At least, I see now why your father didn’t want you coming with me,” Devin said. “Perhaps his plan to hire tutors was just a pretense.”

“Well, I’ll be happy if I’ve helped to ruin his plan,” Gaspard said, yawning. “He can hardly use you to disgrace your father without admitting I’ve done the same to him.” He stood up unsteadily. “I’m going to bed. Why don’t you two figure this out and tell me in the morning.”

“Wait here a moment, Gaspard, while I take the dishes to the galley,” Marcus said. He turned to look at Devin. “You’d better turn in, too.”

Devin snorted. “Who can sleep? There’s far too much to think about.” He watched the door close behind Marcus, glad to see the last of the debris from dinner.

“The day after tomorrow we’ll be off this damn ship,” Gaspard reminded him. “And anyone following us will be far more obvious on land.”

“A sharp shooter doesn’t have to be close to be effective,” Devin muttered.

Gaspard shook his head. “It’s not like you to be so maudlin.”

“I’m just annoyed that a simple trip could be used as a political weapon. I wish my father had been completely honest about why he wanted me to stay home,” Devin said.

Gaspard grunted. “And would you have listened to him?”

“Maybe, if I’d known what was at stake and I’d have to watch for assassins at every turn.”

“Let me do that,” Marcus said, as he slipped back through the door. “That’s why your father sent me.”

“See you in the morning,” Gaspard said, giving him a crooked salute and stumbling out into the passageway.

“Goodnight,” Devin said, making no move to get up. He noticed the satchel in Marcus’s hand and frowned. “You’re not planning to sleep in here, are you?”

“Your father entrusted me with your life,” Marcus replied, putting his satchel on the opposite bunk. “Locks are no deterrent to this intruder, so I’m not going to leave you alone.”

“But your cabin’s just next door,” Devin pointed out.

“I’ve learned only too well that an instant can mean the difference between life and death,” Marcus replied. “Gaspard may scoff at that red cross but I take it very seriously.”

Devin took off his shirt, pulled off his boots, and lay down. He stared at the ceiling, thinking how little he really knew about the man who was sharing his room. His first memory of Marcus was the day after his seventh birthday. His father was dedicating a new park along the Dantzig. The entire family had accompanied him for the celebration. Clouds had scudded across a brilliant blue sky and sailboats dotted the broad river.

They were standing near the new fountain. His father had just finished addressing the crowd when a man suddenly darted forward, a knife in his hand. Andre, already a graduate assistant at the Académie, had grabbed Devin, shielding him with his own body. But the assassin had only targeted the Chancellor. From the protective folds of Andre’s jacket, Devin had heard a startled cry, a scuffle, and the dull thud of a body hitting the cobblestones.

Afraid for his father, Devin had pulled away in time to see Marcus pinning the attacker to the ground. The abandoned knife skittered across the pavement. His father was safe and unhurt, thanks to Marcus’s quick action. Oddly enough, after all these years, two things still troubled Devin about the incident. The first was Andre’s selfless disregard for his own safety. The other was the haunting image of a single tear running down the cheek of Marcus’s prisoner as he lay prostrate on the cobblestones.

Devin turned to look at Marcus sitting on the bunk across from him.

“The day my father was attacked in Verde Park, why did the man cry when you caught him? Was he hurt or simply frustrated that he wasn’t successful?”

Marcus stopped unpacking his belongings. On the table between them he had laid out two pistols, three knives, and a lethal looking coil of wire. He looked up at Devin.

“I wouldn’t have thought you’d remember that. You were only a baby at the time.”

“I was seven,” Devin corrected him.

Marcus closed his satchel and shoved it under the bunk. He loosened the buttons on the neck of his shirt and lay down, his hands folded behind his head.

“Your father was attacked by Emile Rousseau, a stone cutter from Sorrento. Emile had made three requests for sponsorship for his son, Phillippe. The boy was bright but not very strong physically. Emile felt he deserved to be educated. He was anxious that his son be removed from working in the stone quarries. Your father had a great many other things to deal with at the time. He had already sponsored a number of boys, and for one reason or another he postponed his decision about Emile’s son. About three months later, there was an accident at the quarry; Phillippe was crushed between two slabs when a cable broke. Emile blamed your father. He traveled for nine days on foot to reach the capital and kill him.”

Devin found it difficult to breathe. “What happened to him?” he asked.

Marcus extinguished the oil lamp on the table between them.

“He was executed,” he answered. “Now get some sleep.”