Читать книгу Lucky Strike - Nancy Zafris - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

NINE

ОглавлениеJean found a place outside the tent and lay down. Each time she turned her head she had a surreal moment when the big silver bullet came into view. The light from the moon bounced off it. The man and woman were inside. It was quiet. She could almost pretend they weren’t there. She wondered if she owed Harry an explanation of some kind about Charlie’s lung disorder. The name of it had stayed back in Dayton and everyone, even Charlie, felt better for it. Charlie looked healthier and stronger, and he was certainly happier.

She went inside the tent and stretched beside her children. It was a big tent with sturdy framing. It had taken up a big part of the widow’s walk-in closet. She could use Harry’s help breaking it down. She remembered how the widow had almost balked after going to the trouble to advertise it. The widow had acted as if she were putting the tent up for adoption. Her eyes narrowed at Jean after each question and Jean had felt herself grow nervous, as if there were right and wrong answers about one’s intentions concerning a tent.

The canvas sucked in, then flared out. A wind had kicked up, and with it blew in the sudden hint of perfume. The same perfume she had smelled in the widow’s house, in the dead husband’s closet. So now she saw it. The other woman had been here in the tent with the husband. She had always thought it odd the way the widow had sat her down and interviewed her. How strangely covetous of the tent the widow had been. Perhaps she was reluctant to let go of the symbol of her widowhood. Perhaps she liked kicking the tent, booting the other woman each night before she went to bed. Perhaps, growing older and ignored, she was reluctant to let go of this minor power she had over another’s desire. “What exactly are you going to do with it?” the widow asked Jean suspiciously. What exactly, as if there were so many wicked things one could do with a tent.

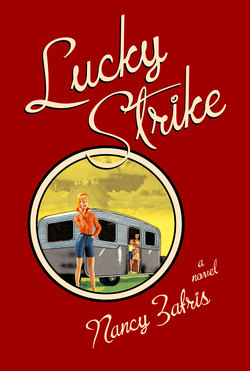

The wind outside reminded her of Ohio. She heard a train in the distance and waited for its whistle. The train bore down and she jolted up and scrambled outside. For a second she twirled helplessly in a circle. “Get up, get up!” she whispered frantically to her children, dropping to her knees and pulling them from the tent until their limp arms sprang to life. They ran to the Rambler and she shoved them in. She tripped toward the road and found Harry there and she was shaking. “It’s all right,” he told her. “We’re up high, we’re not in a pour-in. Do you think I’d let you stay in a spot that would flood?” For a moment she was sorry she didn’t treat him better. The rain twisted through and they sat in the Rambler and watched it. Water poured out in two spouts from the back of the red pickup. The rain beat against the aluminum trailer, its smooth silver like wet skin in the moonlight. She thought of the widow’s husband and the other woman, in the rain somewhere, in their tent, far away, their skins wet. They would have been safe in the rain. They would have been far away. No one would ever know.