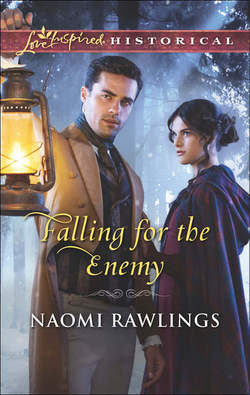

Читать книгу Falling for the Enemy - Naomi Rawlings - Страница 10

ОглавлениеChapter One

Countryside of Ardennes, France January 1805

Blackness pulsed around him, reaching its icy tentacles out to swirl about his feet and beneath his coat, up his torso until it nearly froze his skin. The tree branches clattered above, scrawny and bare of leaves as they scraped together like skeleton fingers. But Gregory Halston, third son of the sixth Marquess of Westerfield, remained still despite the foreboding sense that permeated the night, shrouding himself against a centuries-old oak as he stared at the fortified castle in the center of the field.

“Do you see them yet, Lord Gregory?”

“No.”

But they had to be coming. Any moment now. Too much planning had gone into this night for something to go awry. The journey across the English Channel and a hostile country at war with his own, the exorbitant funds paid for a guide to lead them through a land that had been fighting for nearly a decade, an even larger sum paid to bribe a cook and a guard to sneak messages, ropes and a sack of supplies to a certain pair of prisoners inside.

The endeavor was worth every last guinea.

Or it would be, provided the plan worked.

“Shouldn’t they have been here by now?” Farnsworth whispered. “And our guide has yet to arrive.”

Gregory clamped his teeth together. While valets had their uses in London, bringing his on a trek across war-ravaged France wasn’t one of his brightest ideas. “I realize that, thank you.”

“Do you want me to check my timepiece?”

“As that would involve lighting a lantern and likely alerting the guards to our presence, no.”

“I could always—”

“Farnsworth, stow it.”

The man grunted, and Gregory blew a breath into the silence, keeping his eyes pinned on the shadowed castle. Four rectangular walls jutted toward the sky, with looming guard towers anchoring each corner and a moat surrounding the entire structure. As a fortress, it would have been impregnable. Now that it functioned as one of Napoleon’s secret prisons, unauthorized entrance was utterly impossible.

What had his brother done to get himself jailed behind that massive stone edifice?

Gregory swallowed the lump forming in his throat. What Westerfield had done mattered little compared to getting him out. Unfortunately, Westerfield and his friend Kessler, the future Earl of Raleigh, had been imprisoned together, and rescuing one meant rescuing the other.

Gregory reached down and slid his palm slowly over the bullet scar in his thigh. He’d be happy to see his brother, yes. But as for the man who had faced him across a field at dawn nearly two years ago?

He would prefer to let him rot in prison.

“Do you think they had trouble deciphering the appointed time?” Farnsworth asked from beside him.

A trickle of apprehension started at the base of his neck and dripped down his spine. If only it was something so simple as a misread number. If only something hadn’t gone wrong inside those castle walls.

“Perhaps they mistook your two for a three.”

A dark blob, barely visible in the nighttime shadows, appeared through the opening of a second-story window, followed by a second blob.

The breath rushed from Gregory’s lungs. They were coming. Everything was according to plan, just a bit late. In another moment their guide would arrive, and they could head across the hills and fields toward the coast, and then on to England.

He ran his eyes over the shadowed forms, now inching slowly down the wall with nothing but ropes to hold them. But there were only two. Where was the third? Had something happened to the guard who was supposed to escape with them, the one who had smuggled the black cloaks and ropes into the prison? The one that was supposed to “accidentally” drop a key when delivering food this night?

No, nothing could have happened to him. Westerfield and Kessler wouldn’t be climbing down the castle wall if not for the guard, and the guard couldn’t have changed his mind about the escape. Gregory had already paid the man half a fortune, and once he reached England, the information he could provide about Napoleon’s police and secret prisons would net him another.

Perhaps the guard was one of the blobs and something had happened to Westerfield or Kessler.

Gregory tightened his hands into fists at his side. Just as long as his brother was one of the escaping forms. But with both men hidden beneath heavy cloaks as they inched down the dark castle wall, he couldn’t distinguish which was Westerfield—if his brother was even there at all.

He slanted a glance at the nearest guard tower, where lanterns cast their narrow beams through the windows and into the field beyond. No call rang out from the guards. A few more moments, a silent swim across the little moat, and two men would be free.

Please, Father God, let Westerfield be one of them.

Just then a cough ricocheted against the quiet waters and one of the men slipped, dangling precariously from the rope.

A wave of ice swept through Gregory. He turned toward the tower. Had the guards heard? Surely they must have. A cough like that couldn’t be ignored against such a silent night.

But no shout sounded from the tower, no extra lantern appeared at the window to better illuminate the out-of-doors. Nothing happened whatsoever.

Thank You, God.

The figure on the rope righted himself and climbed down the last few feet, slipping silently into the water. A moment later, the first escapee disappeared into the black depths.

“Stay here, Farnsworth.” Wrapped in his own dark cloak, Gregory broke away from the line of trees and headed toward the moat. His breath puffed hot against the cool winter air as he stood exposed.

Half a minute passed, then another. He stared at the calm surface of the water. How long did it take to swim a moat? Could something have happened underwater?

To both men, no less?

He wiped his damp palms on his thighs, though his gloves prevented the action from doing any good. This was something they hadn’t taught him at Eton and Cambridge, how to enter a country he was at war with and effect a prison break. All those useless hours sitting in lectures, studying and writing essays, and for what? The two schools hadn’t even taught him how to duel.

A head full of matted blond hair broke through the top of the water and heaved a gasp. Kessler.

Gregory’s leg wound, though healed for over a year, smarted afresh. He crossed his arms over his chest. The rat could climb out of the moat on his own.

But Kessler didn’t climb out, at least not immediately. Instead, he looked up, his face thin and drawn.

Gregory hardened his jaw. He’d known he’d see Kessler again, but it should have been in England surrounded by his family, not here on a field outside a prison in northern France. Not after he’d just helped the man who’d shot him to escape.

“Halston...” The world grew still around them, and even the lapping of the water seemed to cease, as though the air itself held its breath in anticipation of what Kessler might say.

Kessler stayed in the water, which had to be frigid given the cold January temperatures, and for a moment it seemed he decided to keep quiet. Then Kessler hefted himself onto the bank, the tendons in his emaciated hands and forearms stark even in the blackness. “I’m sorry.”

The breath exploded from Gregory’s lungs. His wound had become so infected he’d almost died. What was he supposed to do with an apology?

A small splash rippled the water, and he tore his gaze away from Kessler to the dark head full of shaggy hair surfacing at his feet.

“Westerfield.” The name felt odd on his tongue. His brother had been a mere heir to the Marquess of Westerfield when he’d entered France during a short-lived period of peace all those months ago. Now he was the marquess himself, and their father—the man the world had once called Westerfield—was dead.

Gregory held out a hand to pull Westerfield from the water.

The palm that reached up to wrap around him was naught but bones, with a grip so weak a child could break it. What had these despicable Frenchmen done to his once-strong brother?

Gregory hauled Westerfield out of the moat and wrapped his arms around him. Never mind that the embrace soaked his cloak and shirt. Never mind that they hadn’t time for such things until they were at least shrouded in the shelter of the trees.

A horrid stench rose up around him, sour and reeking of urine and vermin. He nearly broke his hold, would have, except Westerfield’s gaunt hand had only been the beginning of the horrid discovery. The man was so thin he might well be more corpse than human.

“Did they feed you?”

“On occasion.” The rasp in his brother’s words made the once-familiar voice barely recognizable. Westerfield sagged into him, as though too weak to stand on his own. Then a cough racked his chest, ringing out over the water and up the castle walls.

“Get him to the trees,” Kessler murmured. “You can greet each other there.”

Gregory wrapped his arms tighter around Westerfield, bracing him more than hugging him. Was his brother ill? That hadn’t been reported. The guard had claimed Westerfield and Kessler were both in excellent health.

Gregory looked at Kessler. Though the man stood covered in a sopping black cloak, ’twas plain from his pronounced cheekbones and the drawn way his skin sank into his face that he’d fared little better than Westerfield. “There’s only the two of you?”

Kessler frowned. “Yes. Were there supposed to be more?”

“I arranged for three escapes, the last was supposed to be the...”

A lantern appeared in one of the lower castle windows, voices carrying across the moat.

“Could there have been an escape?”

Despite Gregory’s rather basic understanding of French, the meaning of the words was clear enough.

“Non. No escape, not here!”

“One of the cells below is empty.”

“I know nothing of it.”

“Wake the guards, and search the castle. The men couldn’t have gotten outside these walls.”

“What if they did?”

“We must hasten,” Kessler growled quietly, then wrapped an arm beneath one of Westerfield’s shoulders.

They scrambled toward the trees together, stopping only when they met Farnsworth. But the tree line could offer only momentary respite. They needed to get away, yet the guard hadn’t made the escape, and their French guide was still missing.

Westerfield coughed again, the bone-deep sound jarring against the otherwise still night. “Slower next time.”

A call rang out from somewhere inside the towering stone walls of the castle, followed by an echo in response. Gregory didn’t look back to see whether more lanterns had appeared in the windows, but he could well guess the next cry before it left the mouth of a distant guard.

“Escape!”

The shout reverberated across the field and bounced against the trees.

A cold dread filled his chest. They’d been betrayed.

And stranded.

In the middle of France.

At the center of a war.

He glanced briefly around his group. Four men, all unmistakably English. Their clothing and coin might be French, but their tongues were English. They could manage to speak some French between them, yes, but not without accents.

By this time tomorrow night, they’d all be rotting inside a dark French dungeon, and something told him their new home was going to make the horrors his brother and Kessler had endured look trivial in comparison.

* * *

Danielle Belanger crouched beside the campfire and laid another stick on the licking flames, then sighed.

Another task failed.

Oh, she’d been sent to Reims to visit with her aunt, true. And the visit had gone rather well. Her mother’s sister was kind, generous, well respected...

And had tried introducing her to every decent, unmarried man in the city.

Those meetings had turned out about as well as all her introductions to men in her hometown of Abbeville.

Two and twenty years of age, and no one wanted to marry her.

Not that she wanted to marry any of them, but most girls four years her younger were happily married and bearing babes. Shouldn’t she have had at least one marriage proposal by now?

Or rather, she’d had one, she supposed.

Well, more like a dozen. But none of them from men any sane woman would marry. Perhaps if she was blind and docile and preferred spending her days mucking stalls and spinning yarn, she could be happily married. But she certainly didn’t take to mucking stalls—they stank too much. Or spinning yarn—one had to sit far too still to manage such a task. She wasn’t blind, and as for the docile part, well...

“I could only get one.” Serge, her younger brother by six years, emerged from the tangle of trees and shrubs lining the creek. A squirrel dangled from his hand by the tail.

She rolled her eyes. “Go back for another, then.” He held out the squirrel for her to take. She merely crossed her arms. “Papa said you need to practice.”

“Come on, Dani. You can have it skinned in half the time.”

Which was likely why her younger brother had reached sixteen and was the slowest animal skinner in all of Abbeville.

“I caught and cleaned the rabbit last night. It’s your turn.” She eyed the bloodied animal, a large stab wound gaping in its chest. “And you’ve little choice about going back for more. Mayhap we could have shared just the one had your blade hit between the eyes. But knifing it in the chest like that, you lost too much meat.”

Which her brother should have known.

Maybe he wasn’t just the worst in Abbeville at handling a knife. He had to be the most inept in all of northern France.

She pushed up from her crouched position by the fire and stood, stretching her back before turning to head upstream.

“Where are you going?” Serge called after her.

“To look for berries.”

“In January?”

She shrugged. So mayhap she wouldn’t happen upon berries, but she might find some burdock or cattail root to dig. Anything to get her away from the fire. If she lingered there, she’d end up doing all Serge’s work, and she could hardly sit still long enough for him to find another squirrel.

He likely wouldn’t return until after dark, the dunce.

She made her way along the water, sluggish from the coolness of winter, but not frigid enough to turn to ice. Leafless brambles and shrubs sprang from soil still damp from yesterday’s rain. She shivered inside her cloak and glanced up at the gray sky through the tree branches above. Home would be more temperate than this, near enough the channel’s warm waters to drive winter’s chill away.

Something rustled ahead, then a rabbit scampered out from beneath a bush and darted toward a little thicket. Within half a second, she had her blade in hand, her fingers gripping the familiar leather handle. One throw, quick as lightning and silent as a snake, and she’d have their supper.

Except Papa had all but commanded she let Serge do the hunting on their trip, saying he had to learn sometime. And she’d done most of the hunting on the way to Reims, then yesterday, on the first day of their journey, she’d killed a rabbit.

She was going to be good and obedient—for perhaps the third or fourth time in her life—and let Serge do tonight’s hunting. She sighed, her grip loosening on the knife.

As though sensing the sudden lack of danger, the rabbit stopped and turned, sniffing the air before staring straight at her.

Too easy a kill to bother with now anyway. What was the fun of throwing a knife when her target was still rather than moving? She bent and slipped her blade back against her ankle and continued down the little stream, winding her way deeper into the woods.

She could almost see the resigned look in Maman’s eyes and hear her exasperated sigh when Maman realized her eldest daughter had returned to Abbeville husbandless. Two towns, with a suitable groom yet to be found. Two! Papa claimed God had a plan for her. That she only needed to wait on Him, and everything would fall into place.

Evidently Papa didn’t understand how hard it was for her to wait for anything—let alone for God, Whom she couldn’t see or touch.

As though waiting for the right man to happen along hadn’t already taken long enough.

A rustling sounded from the trees behind her. Likely another rabbit. But no, the noise was too loud for such a small animal. A fox, perhaps?

She stilled until only the trickle of the creek over rocks and the tapping of tree branches in the wind filled her ears. Another sound, deep and rich, carried on the faint breeze.

A distant, undeniably male voice.

She reached for the knife strapped at her ankle once more, then straightened, stepping stealthily around twigs and through a tangle of saplings.

Probably not anyone to worry about. Just another traveling party stopped to make use of the stream.

Except they were settled awfully deep into the woods to be merely traveling.

Then again, she was nestled rather deeply into the woods, as well. But the trees provided ample opportunity to find game, and with only her and Serge, she didn’t want to invite trouble. She could defend herself well enough, ’twas true, but she wasn’t going to seek disquiet, either.

A different person would probably turn around and head back to the campsite, pack up and move another kilometer downstream before settling in for the night. That would certainly be the safe thing to do. The predictable, normal, safe thing.

But then she wouldn’t know who the travelers were, whether they posed a threat.

She crept closer to the voices. The cadences were low, all male but slightly different. She slipped silently between two shrubs, years of moving quietly through the woods while hunting with Papa aiding her stealth. She only needed to creep a bit closer.

Something about the voices didn’t sit right. The intonation seemed off, rough and coarse, without the gentle roll of French off one’s tongue. Perhaps if she overheard a word or two, she could better understand why they were camped so obscurely. The men could be anyone from gendarmes to army deserters to thieves.

Or they could be normal travelers having just left Reims and heading toward the coast like her and Serge.

Either way, she needed to know.

She crouched lower and inched forward. Something moved ahead, a flash of cream on the other side of the brambles. Then a cough sounded, loud and harsh and from deep within the chest.

Whoever made up this party, one of their members seemed not much longer for this world.

A gruff voice filled the air. “I still say we’re better to travel during the day.”

The breath in her lungs turned to ice. She couldn’t have heard right. No. Certainly not. It almost sounded as if they spoke...

“He’s right,” another man rasped, followed by a small cough. “We can’t travel at night. We hardly know which way to go during the day. We’d be lost within a matter of hours.”

English.

She swallowed against her suddenly dry throat. That vile country’s navy had killed her older brother. If she never saw another Englishman or heard the language spoken again, she’d be happy, indeed.

But what were a band of Englishmen doing here?

She squeezed her eyes shut. No. Never mind. She didn’t want to know.

Definitely didn’t want to know.

Most assuredly didn’t want to know.

She simply needed to get herself and her younger brother away from this place.

She began to back away as stealthily as she’d crept up. Except, with her hands shaking and her heartbeat thudding wildly in her ears, she wasn’t stealthy at all. Clumsy, more like. Her foot cracked a dried twig, and her cloak brushed against the brambles. She paused for a moment. Had they heard?

“We’re lost now.” A third voice, higher pitched than the first two and with a hint of intelligence behind his words, spoke.

She let out a silent breath. They’d noticed nothing. Now she need only move quietly—because she could be quiet if she didn’t let panic get the better of her—back through the brambles. Then she’d find Serge, and they’d pack up camp. Dinner could be some of the salt pork and bread they carried. No need for freshly roasted squirrel now, not when they had to find a gendarmerie post and report the Englishmen.

Because Englishmen traveling through France during the middle of a war could only be spies.

What secrets would these men impart to the British government if they reached the coast and no one stopped them? She was glad they were lost. They could walk around in circles for the next week.

Except by then, she’d have found that gendarmerie post and explained everything. A week hence, those British spies would be moldering in some nameless dungeon, likely being tortured and pouring forth whatever secrets they’d discovered about her country.

Which was exactly what they deserved.

But first she had to get away without anyone noticing.

“What do you want us to do? Stop and ask for directions?” The third, intelligent-sounding voice dripped with sarcasm. “Or perhaps a map? I’m sure there’s a very welcoming gendarmerie station along the road to Saint-Quentin. We need only present ourselves and say, ‘Good day, sirs. Could you tell me the quickest way from here to the channel? You see, I’ve two es—”

Something crashed in the woods behind her. Danielle whirled, the leather handle of her knife clamped tightly between her fingers. But too late. A male body slammed into her from the side and crashed her to the ground.

Shrubs scratched her arms and tore at her cloak as the man rolled himself over her. She fought as he struggled to sit up while holding her to the ground. He wasn’t overlarge or terribly strong, but he plunked himself down directly atop her while trapping the forearm that held her knife beneath his knee. If she could only find some way to upend him...

“Come quickly! I’ve found a spy.”

A spy? Her?

She wasn’t a spy. She was just...well, spying, but not for the reason they thought. They were the spies, and she’d only wanted to make certain she and Serge were safe from the men camped so close to their own site.

Or rather, that’s all she’d wanted to do until she’d discovered the mysterious men were English.

“What’s that you say?” The English voices grew closer and footsteps thudded on the muddy ground.

“You found someone?”

If she was going to get free, she had to do so quickly. She’d not lie there docilely while men from the same country that had killed Laurent attempted to capture her. She brought her knee up, trying to uproot the oaf’s bottom. The man only gripped her shoulders and pressed her harder against the damp earth. She twisted and turned, but his weight made it difficult to suck in air and his knee still pinned her knife hand.

“She was watching from the bushes,” her captor explained. “I wouldn’t have spotted her except she started moving as I was coming up from the stream with the water.”

Danielle pressed her eyes shut and stifled a groan. She should have considered someone might be at the stream, should have thought to scout the area before she’d even started into the bushes. Instead, she’d turned into a complete and total idiot at the sound of one simple phrase in English.

“What’s your name?” the intelligent voice asked in English.

She opened her eyes and stared at the tall form above her, with tousled dark brown hair, an arrogant, aristocratic nose, and eyes the color of fog over the ocean. Not quite gray but not quite blue, and just mysterious enough one might stare into them a bit too long, trying to understand—

“Her name matters not,” a deeper voice snapped. “How much did she overhear?” Another man appeared above her, leaner and taller than the first, with a face so thin and wan the bones seemed to jut from it. His hands appeared just as bony, as though he hadn’t had a good meal in the past half decade. But his emaciated body didn’t stop his shrewd green eyes from narrowing at her.

She licked her lips. What should she tell them? She hadn’t overheard much beyond that they were lost and debating when to travel. Could she pretend as though she didn’t know English and hadn’t understood a word? They had little reason to suspect a woman such as her would know their language.

And even if she wanted to answer their questions, she couldn’t manage to speak more than a word or two with an English ignoramus sitting atop her stomach and squishing the air from her body.

“I daresay she didn’t overhear anything,” the raspy voice spoke from the other side of the brambles. Then that horrid coughing filled the air again.

“A woman like her isn’t going to know English,” the dunce atop her proclaimed. At least he was useful for something besides squishing the breath from her body. “Lord Westerfield is right.”

Lord Westerfield? She nearly groaned, would have if she possessed the ability to breathe.

She moved her gaze between the two men standing above her, their patrician noses and arrogant bearings suddenly more than mere circumstance. As if finding regular Englishmen hiding in the woods wasn’t trouble enough. She’d somehow stumbled into a nest of aristocrats.

Just her luck.

“Try in French, Halston.” The thin blond man nudged the darker haired one—Halston, evidently.

Halston scowled at the other man. “You try in French. You’re the one who’s spent the past year and a half in this wretched country.”

“The only French I found use for were curses. The rest of the language I’d like to forget as quickly as possible.”

Danielle bit the side of her lip. This was probably supposed to be the moment she turned grateful for all those horrid English lessons her mother had forced upon her while growing up.

Except she still didn’t feel all that grateful—though it was rather helpful to know what they were saying instead of being left to guess their intent.

And now that she had a moment to consider, she’d best not speak in English. She might lay pinned beneath a wiry man who felt far heavier than he looked, but she still had two things to her advantage. First, her captors didn’t realize she understood their words, and second, they didn’t know about Serge.

If she managed nothing else from this debacle, she would at least keep them from learning of her brother.

“Stand her up, Farnsworth. Let’s have a look at her,” the blond commanded.

“She’s a person, Kessler, not some dog,” Halston growled.

The two men stared at each other, the air between them igniting like the sudden spark of a flintlock. Then Kessler turned away and the man atop her began to rise.

She tightened the grip on her knife, waiting for the perfect moment...