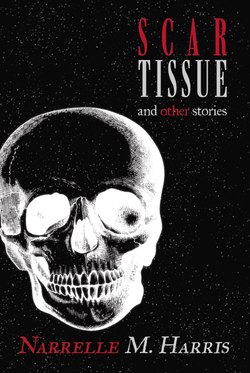

Читать книгу Scar Tissue - Narrelle M Harris - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

HOORFROST

ОглавлениеAuthor’s note: This is an origin story for Kitty and Cadaver, about a rock and roll band that fights monsters with music.

London June 1258

If anyone but Will knew what was causing this snow – that thing in the river – they weren’t doing anything about it. Will was, though. He was swearing.

‘God’s nails!’ Will swore as he trudged through the fresh fall of snow. He suspected he’d wandered off the road to the Ludgate. Surely this grove of elms was further west than he meant to be? He couldn’t see the sun, much less any shadows, to judge the time in this milky light, but it must be no later than the third hour, barely half way to noon.

The air was cold enough that his swarthy skin – heritage of a Spanish mother with Moorish blood – was relatively pale in the frame of his dark hair. His dark eyes ached in the glare of the snow and cloud.

He cursed as his feet crunched down.

God curse this winter and the famine that it brings; God pity the thousands dead for want of food. God curse the frozen Thames and the strange skies of this unspeakable winter. God curse the even stranger thing that lurks in the river’s mud.

And triple curse this cocking snow that will not cease falling.

When cursing didn’t help, Will tried to spell it warmer with a rhyme.

Un-freeze, damn’d-dirt, God’s-heart, it’s-cold.

His teeth chattered too hard for the chant to be spoken, and numb with cold as he was, it was a poor chant. The result was weak – he never could make much use of water; earth responded best to his call – but the beat of it kept his body moving, less cold than if he stood still. He’d have unslung his tabor, but the drum’s skin was brittle with frost. Even encased in fur gloves, his hands were stiff. At least he had boots, and the moss stuffed in the left stopped the snow leeching in through the hole and biting his heel.

Having no lodgings, St Martin’s Le Grand’s curfew knell last night had forced Will to sleep beyond the city walls or risk prison. He’d sheltered in St Bartholomew’s Priory – its founder had been a minstrel, and the brothers there had given him water and a bite of what little bread they had. This morning he’d left, hoping to find some scraps.

But the bells of St Martin’s Le Grand hadn’t rung to herald the opening of the markets, and that was how William Hawk knew he no longer had a choice in what he did next. Whether the problem was no bell, or no markets, the silence meant this unnatural winter was deepening and a cold and hungry death was coming for them all.

He didn’t know what to do about the thing in the river either, but he would make his way back into the city to do it. If the church was wrong and God loved him after all, he would succeed.

A sweet, fluting sound pierced Will’s cursing and he halted, listening.

It was the trill of a pipe, played dancingly by a musician of rare skill. Will felt warmer just hearing it. And then his fingers ached less. Will grinned with sudden certainty. He followed the music through the woods and paused when he found its source.

A young man knelt on the ground in a circle of bare earth, playing his pipe. His dark blond hair stood up all over his head, as though he’d spent the morning scratching through it. The cold made his cheeks ruddy, and his grey-blue eyes were dark-rimmed with fatigue.

The melody he played was intricate, dancing swiftly through flurries of notes. The melody line was strong and the notes around it did not rise and fall so much as build and flicker.

In the centre of the ring of earth was a fire, small but bright, fuelled only by air and music. The ground on which the piper sat was dry, but beyond him the snow was pristine, freshly fallen white, marked with the footprints that showed the way by which the piper had come.

Will stepped out of the shelter of the trees.

‘God give you good day, friend.’

The music stopped abruptly and the young man rose, his wooden whistle clutched in his left hand, a knife in his right. His stark glare was equal parts anger and fear.

Will held up his hands, palm out.

‘Peace, friend. I too am a musician,’ he gestured to the drumsticks tucked into his belt. ‘Shall I play for you?’ He reached slowly for the sticks without waiting for a reply.

The other did not lower his knife, or move, or speak.

Will fetched his sticks but didn’t unhitch his tabor. He knelt. With the side of his hand, he pushed aside the snow to reveal the frozen ground. He pulled the gloves off his chapped red hands, took up his sticks, and beat the ground with one stick, then the other.

‘Look to your fire, good fellow,’ he said, and sang as he played the tattoo.

Slumber not, oh root and seed

for Winter has now overstayed

Earth bring forth thy buried tinder

Let fire feed; the frostbite hinder

The fire feeding on air was fading, but the ground beneath it was heaving, cracking, as the fallen branches of the autumn and early winter broke through, pushed on the backs of shifting roots. The fire licked down towards the dry wood and took hungry hold. It crackled and burned brighter.

The heartbeat drum, the breathing fife

We play to ask you give us life

The strength you had when spring did turn

Release as bones of trees to burn

And flamed higher still.

Will stopped playing and the cosy fire feasted on the fuel that the earth had given them.

‘We are brothers,’ said Will to the astonished man. ‘Fear no harm from me.’

The man considered this, then finally put away his knife. ‘Sit by the fire, then. Maybe we’ll be friends. My name is Thomas Rowan.’

‘And I’m William Hawk. The friends I once had called me Will.’ He sat next to Thomas Rowan by the fire.

‘You once had?’

‘Most are dead now,’ Will said. ‘Famine and disease, mostly, though sheer cold took its share. My fellows in music. They froze to death on the road a week ago. I dared the charge of heresy and witchcraft to keep us warm and alive, but they fled in terror of me.’ Will stared into the fire. ‘And therefore are too dead to denounce me a heretic.’

Thomas shifted restlessly. ‘My brother had a lovely voice,’ he said at last, his own dark with sorrow. ‘He tried to sing some safety for us in Lord Hanley’s hall, but Hanley hadn’t enough to feed us either, so now Dickon is lying with all the others at Spitalfields, waiting for the ground to thaw enough for burials. I hoped to find some other fortune before I joined him as food for worms.’

‘I’m sorry for your grief, brother Thomas.’

‘And I for yours, brother Will. Where are you going now? Or are you, like me, walking towards death rather than wait for it to come hunting?’

‘Walking towards death, I suppose. This winter’s taken everything I had, but there’s a cause for this bitter season. Something sits in the mud beneath the Thames. I fear it’s addled with some ancient, raging sorrow. I feel it when I play the earth. I don’t think it means to destroy us, but this strange winter has woken it.’

‘You sound sorry for it.’ Thomas was not pleased.

‘Not really,’ said Will. ‘The death it brings may not be its intent, but death it brings all the same.’

‘You think to kill it?’

‘I don’t know what it is; still less if it can die. I thought I might try to sing it back to sleep.’

‘And if it doesn’t want to sleep?’

‘I die. But I’ll die regardless, in this cold. I’d rather die trying to live.’

Thomas considered this philosophy with a frown.

‘How will you make it sleep?’

‘I could sing a cradlesong to it. I’ve sent many to sleep in my time as a minstrel, but that’s only ale and my voice.’ Will laughed wryly and his breath puffed in cloud. ‘I can sing a little magic, but it speaks best through my tabor. Usually I use it to keep bugs from biting, or dry the ground when it rains. Little tricks that hurt none and comfort only me. But I once drummed a stalking wolf into curling like a puppy at my feet, and when I was a boy, a spirit rose from a ruined hall and tried to possess my father. I beat the stones with my hands and sang the ghost to pieces. This thing is doubtless stronger than wolves and ghosts, but I’ll die fighting it rather than starve or be frozen blue at the side of the road. What say you?’

‘My pipe isn’t as clever as Dickon’s voice was, but it’s yours for this. I’ve a knife as well.’

‘Any tool is useful,’ agreed Will.

The city gates were open but untended. Will and Thomas, filled with disquiet, passed through the Ludgate without hindrance. Without fish to sell, the old fish market was silent. Theirs were the only footprints in Thames Street. The only sound was the caw of a raven to the northwest, where Wall Brook was as frozen as the rest.

The quality of the milky light seemed unchanging, but Will thought he felt the dusk descending by the time they reached the place where the riverbanks crackled with wrongness. The Thames was frozen from shore to shore. Spanning the ice was the London Bridge, built in stone under the reign of King Henry’s father, King John. The Chapel of St Thomas on the Bridge stood lonely in the centre. The Brethren of the Bridge who prayed there were either all at prayer or huddled before fires in their Bridge House. Or perhaps they were dead like so many others. Will saw none, wherever they were.

Thomas had shoved his gloved hands into his armpits in an attempt to keep warm.

‘Where is it then, this angry, grieving monster?’ Thomas’ scowl suggested he had an angry, grieving monster of his own, furled underneath his heart.

‘Somewhere near. I can feel it when I drum.’

Thomas stamped his feet on the snow. Nothing came to the summons. ‘You say the strange winter woke it,’ said Thomas. ‘Didn’t the monster cause this hell?’

Will knelt on the ground with his drum. ‘That’s not what the earth tells me.’

For a man who had woven fire out of air with a fife, Thomas was sceptical. ‘You talk to the soil often, do you?’

‘The earth’s a good listener,’ replied Will, unruffled. ‘She holds many secrets, and sometimes she shares them with me.’

‘What’s the secret of this killing winter, then?’

Will pushed the snow aside, took off his glove and placed his hand on the bare ground. ‘The earth is round, did you know? Full ripe round like an apple but she has a fire at her heart. Sometimes the fire bursts through her skin. She has burning mountains that birth burning rocks, and the smoke of her womb covers the sky.’

‘Mountains have burned and spat rocks and smoke before,’ said Thomas, ‘but winter has only been winter.’

‘This particular mountain burst like nothing before it,’ said Will solemnly. ‘Do you remember the red sunsets in the spring? Colours as violent as blood, the sun lighting on the smoke from the other side of the world? In that fire’s wake, summer never came; then winter came and stayed.’

‘I was here for those sunsets too,’ said Thomas drily. ‘For the failed harvests, the dying cattle, the floods that washed away what little had grown, and then froze the rest.’

‘Well, that’s what woke the thing that slept in the river’s mud. It’s been here longer than that, of course. Hundreds of years.’

‘Does the mud tell you that?’

‘It does.’ Will rested his hands on his haunches and cocked an eye at Thomas, who glared at the road of ice where a river once ran. ‘Curb your anger, brother Thomas. I didn’t make the mountains burn, the skies turn red or the river freeze. I only listen to what the magic tells me.’

Thomas’ eyes did not shift from the Thames. ‘Shall I tell you what the air says?’

‘I’d be most interested to hear.’

‘I hear a lament, William. A voice colder than the frozen wastes of the Viking north cries for Baldr, whoever that may be. It begs forgiveness and for punishment for Hoor. For itself.’

Will listened with all his body and thought he heard something of the lament. A cry crackling with cold; the sound of ice breaking like a heart.

‘I hear it. It must have done something terrible, to sound so.’

‘I’d offer it punishment, if I could,’ said Thomas.

‘You have no pity for the thing?’

‘It killed my sister.’

‘Brother, you said.’

‘Both,’ growled Thomas.

Grief and rage, thought Will, are not the purview of monsters alone.

‘What now?’ demanded Thomas.

‘I never heard this cry before, and I’ve often passed this way. The ash sky brought winter early and woke the owner of this voice, to cry out. Its lament is what makes the winter last so long. I’ll sing a cradlesong, I think.’

‘We should kill it.’ Thomas’ knife was in his hand again.

‘Are you very determined to die?’ Will asked gently. ‘For I think that taking your little blade to this creature will accomplish that nicely. If you’re not so very set on dying, though, I thinking putting it back to sleep may give us a better chance of seeing tomorrow.’

‘What should we do, then?’

Will wouldn’t admit that he didn’t know. All his small magics hadn’t prepared him for the task he’d taken on. Instinct told him to connect to the earth, however, so he walked to the edge of the frozen Thames and knelt on the ice-hard mud. After a moment, Thomas joined him.

Will began with a tattoo drummed on the ground and Thomas began to play a warm melody around it, so that the ground softened and steamed.

‘Play on,’ said Will. He tapped on the ground with one drum stick, tucking the other stick into his belt, and pressed his fingers into the mud to listen to the earth. Will’s fingers felt the pulse of the ground, slow and dark and deep. Wet and steady. The Earth was old and patient. The thing waking in it, though much older than London, was still younger than the ground on which London stood, and younger than the river under which it lay.

With the one hand, Will slowed the rhythm of the tune they were making and sang sweetly to the thing under the mud.

Hush thy heart, great beast

Let sorrow fly away.

Dwell thee not on life’s great hurts

But rest thee while thee may

Softly still thy mind

Let slumber soothe thy pain

Merciful is winter’s end

When springtime starts her reign

Thomas’ playing curled around the beat, but his heart was seething. The result was not a lilting cradlesong but something tight and thick; not a letting go but a squeezing of the fist. Will understood too late. Before he could fall silent, or withdraw, he felt it.

Eyes opened deep in mud and looked right through him.

Will fell back, a gasp of fear trapping frosty air in his lungs. He tried to cry a warning to the piper and couldn’t, so that Thomas’ surprise at the abrupt end to their cradlesong was all for Will landing arse-first on the ice.

And then Thomas’ eyes grew wide and his mouth opened in horror but no sound came out. The piper’s hair stood on end, and so did Will’s in sympathy as the ice crackled and cracked and began to heave, and he knew, he knew, he oh God he knew that the thing that he’d felt looking through him was rising up behind him through the mud and ice, and he knew he would never see the moon or sun or stars again, he would never know warmth or bread again, he would never know love again…

The piece of the Thames on which he sat cracked, heaved, tilted, and he slid down it. One hand still clutched the drum stick, his tabor banged against his back where it hung, the stick in his belt jammed into his ribs.

He crashed into Thomas who had instinctively opened his arms to receive him, and they fell in a tangle on the snow and lay there, arms about each other in terror, for comfort, and looked at the being which had risen from the frozen river.

It almost looked like a man: tall, broad-shouldered, with arms and legs. But its body was made of mud and chunks of ice, pieces of bone and wood. Its chest was the mouldering portion of the prow of an ancient boat, sunk a thousand years ago. Its hair bristled in shards of weed and pottery: clay-brown, glazed blue, fragments of figures and colours.

It shook its bewildered head, scattering sleet. It raised its chin and opened its mouth and howled at the snow-and-ash laden sky.

Hailstones fell. Will and Thomas flung their arms over their heads and they huddled over each other. Fist-sized chunks of ice glanced off their arms, their bodies, bruising them. One struck Thomas on the forehead, drawing blood. Another crashed into Will’s fingers and he felt a bone break.

The man of mud with ice blue eyes roared into the air words they didn’t understand. Waves of grief and rage rolled off the sound and from its body and through their flesh and somehow within the waves of sound, Thomas heard meaning.

I am cursed. I am wronged. I am doomed.

Thomas struggled to his feet with his blood frozen in a streak down his face, and he roared back at the creature who hadn’t even seen them.

‘We are all cursed, all wronged, all doomed! We don’t all destroy the world!’

The creature ceased howling and tilted its head down, then moved it slowly left and right, listening. Its ice blue eyes were unseeing, but its face was wrapped with confusion and irritation.

‘What are you to speak to me?’ it emanated.

‘I’m a man you’ve wronged.’

‘I do not know you.’

‘Yet you did me harm. You killed my brother.’

‘No,’ said the giant. ‘Not brother. Sister.’

‘He was my brother and we killed him, you and I.’

The giant was confused again. ‘My brother is dead. I slew him by mistake.’

‘I killed mine with negligence, selfishness and fear,’ said Thomas. He wept and the tears froze on his cheeks.

‘I was jealous, I admit,’ said the mud-man. ‘Baldr was so beloved of our mother, she made all living things swear to never harm him. The other gods threw weapons at my brother to test him, but beautiful Baldr only laughed as all things kept their promise. But Loki tricked me. He gave me mistletoe, which had been too young to swear peace to Baldr, and in my envy I threw it, ignorant of its power. One little dart of mistletoe from my hand and my brother laughs no more. Baldr was slain at my hand.’ It howled into the air again then slumped, blind eyes turned towards the musicians. ‘Vali killed me in just wrath, but a god never truly dies.’

Will stirred from his watching. He heard Thomas speak to the mud-man, and heard its replies in his blood and bones, through the earth. ‘A god, are you? How is it you’re here?’

‘Loki bound my spirit to an earthen jar. He delivered me to the hands of men to be a talisman. I have travelled far from Asgard on warships, but I never brought those Captains to victory. Another of my brother’s tricks. He never tires of them.’

‘Baldr?’

‘Loki is also my brother.’ It frowned. ‘He is not always my brother. Perhaps my sister too, sometimes. He takes many shapes.’

‘My brother also had other shapes before we killed him.’

‘I did not harm your brother.’

‘A fire on the other side of the world covered the sun with ash and brought a winter cold enough to wake you,’ snarled Thomas. ‘Now you’re killing the world with ice.’

‘I am the god of ice,’ it said, as though such deaths couldn’t be helped.

‘Do you have a name, Loki’s brother?’ asked Will casually.

‘I am Hoor.’

‘I think I’ve heard of you,’ said Will. ‘By the name of Hod.’

‘I have many names.’

Thomas scowled. ‘Well, Hoor of Many Names, you killed Dickon with your cruel winter.’

‘Not alone,’ said the ice god Hoor and his tone wasn’t kind. ‘Negligence, selfishness and fear, you said.’

‘That’s right,’ said Thomas, just as ruthless. ‘We’re a pair alike, we two. Just as you killed Baldr with envy, foolishness and spite.’

Will held his breath, sure from the fury on Hoor’s face that their luck was done and death was coming.

Instead, Hoor laughed, grimly, without mirth. ‘I did.’

‘I know what you did to Baldr. Shall I tell you my tale?’ asked Thomas.

‘Did you kill a god?’

‘A god can’t die, you said, but my sister-brother died twice, first as maiden then as man.’

Hoor bent his head closely to hear more. Will, likewise, listened. His broken finger throbbed but he gripped his drumstick tight anyway, unsure of what to do, or if anything was possible.

‘Lulie was born a rosy lass who could never be a maiden. She never learned the skill of it or to desire that she should,’ Thomas said. His voice rose and fell in storytelling cadences, but it was filled with the sharpness of a secret’s first telling.

‘From youth, my older sister would answer to nothing but Dickon. She was boyish in all things, from her large hands and loud laugh to the careless way she ran and climbed and fought with boys who challenged her wildness. Dickon caused our parents only grief, except for when she sang, for then she sounded like an angel.

‘Dickon would not relent in being Dickon, and would not be made to wive, since her body and her heart to womanly virtues would not strive. Dickon grew tall but lean; her menses would not come. At last our parents gave up persuading Dickon to be Lulie and accepted their daughter was a son. As a family, we buried Lulie as a name. Dickon my brother from that day became.’

Will pressed his hands to the earth and ignored the ache of one broken finger while all the rest tapped faintly in the dirt, picking out the uneven rhythm of Thomas’ story.

‘To me Dickon confessed he’d found a way, a trick of song to make his body obey. To banish his irregular courses and sing his chest flat. I confessed I had my own tricks after that. With my self- made bone and yew pipe I charmed the partridge and the lark to my knife. I fluted fishes to my net, fires to light, clouds to part, warmth to night. We found when I played and Dickon sang, we charmed coins to our purse and our good fortune rang.’

Will felt the dirt under his fingers tremble, though Hoor was, like him, transfixed by the story. Will found in it echoes of a ballad heard last summer. The long tale written by a sarcastic Cornish poet going by Heldris. In the tale, an earl’s daughter was raised as a boy named Silence. “The boy who is a girl” – li vallés qui est mescine in the poet’s hand. What else had the ballad contained? Jo cuidai Merlin engignier, Si m’ai engignié. “I thought to deceive Merlin but I have deceived myself”.

Will already knew this similar story of Dickon didn’t end well. Yet the story compelled, as did Thomas’ telling of it.

‘We brothers thought it easier to sing for wealth than learn our father’s trade, and we did well, until a burning mountain this early winter made. Will says the cold stirred you from your sleep. You brought a bitter cold and we starved, and so my brother’s magic grew weak.’

All Thomas’ rage seemed now self-directed, the nails of his own curled fists biting into his palm, drawing blood. The vibration in the earth under Will’s hands shuddered.

‘Dickon dared not carouse with pages and with squires, the body he’d shaped for himself did not hold true. But I was cold and wished for the warmth of other companionship, and the cheerful comradery that ale and wine imbue. I wished to forget, with men like me, that men may die of want. To spend a night without Dickon’s fear and rage for his body changing, thin and gaunt. So I went to the woods with other men and wasted life and time, and burned fuel that should have had more prudent use, and fed on Hanley’s stolen bread and wine.’

Thomas’ chest was heaving as though he had climbed mountains to tell his tale. His body was trembling with the strength of his feeling, which fortunately also masked the insistent tapping of Will’s nine healthy fingers on the ground. Will was getting the hang of the rhythm now, thrumming under the surface of the earth, under the surface of Thomas’ tale, and under the surface of the ice. A small magic, unheeded as yet by the blind monster.

Will thought he saw something moving in the air, a flap of dark wings. He thought he felt something moving in the sluggish water under the ice, a deep river green. He didn’t let himself be distracted, but continued to tap the beat and listen to the words Thomas spoke. There was no spell in them yet, but for all that, they were spellbinding. Hoor, unspeaking, listened hard to every word.

‘I returned, drunk, to find Lord Hanley, seeking his unfaithful staff, discovered my poor Dickon whose face and body were womanly round and soft. He could not find the thieves of wine and wood, so he punished the one who had lied to him, though done less harm than good. He locked Dickon in the snow and ice in a pen beside the woodshed, and that’s where I found my brother-sister frozen, where he fell and broke his dear head.’

The air almost hummed with the tension of this ending, the death of Dickon.

‘Negligence, selfishness and fear,’ said Hoor. ‘But yours was not the hand that slew your dear.’

Did Hoor know he’d spoken in this land’s English tongue, and made a rhyme to add to the magic all around?

‘Yet I’m culpable. Dickon died because of me. He also froze to death because of you. The fault is ours to share or refuse equally. You who your brother with envy, foolishness and spite slew.’

Hoor’s voice rumbled in its chest of mud and ice and bone, a dark agreement at the remorse.

‘What should we do, we guilty brothers?’ Thomas asked. ‘Would our own deaths make amends for what we’ve done?’

‘I will find redemption or annihilation at prophesied Ragnarok. What fate do I deserve? What should my fate become?’

‘Await your final reckoning undisturbed in the mud.’

Will’s hands had taken up the rhythm from his aching fingers. His broken finger was swollen but numb. He had begun to hum under his breath.

Hush thy heart, great Hoor

‘I am weary with the waiting,’ grumbled Hoor. His ramshackle face began to sag.

‘Become undone, as was my brother in his blood,’ said Thomas, only he was singing now. Will sang softly beneath Thomas’ loud, clear voice.

Hush thy heart, great Hoor

This body be not thine

‘What are you doing?’ demanded Hoor.

Dwell thee not on rage and pain

This England is not thine.

Wet earth and mouldering rubble sloughed away from the body Hoor had made for himself. For a brief moment, he diminished – then, alarmed, enraged, he opened his muddy maw and roared. His body began to form again. Made of mud, stone, ice, slaughterhouse bones and the waterlogged hulls of sunken ships, he reared up three, four, five times as large as before. God-like truly in his fury, yet like a mortal in his desperation.

He raised his arms, as if to bring them smashing down.

Thomas’ voice joined with Will’s then. Neither had sung this song before, yet the words came to them both, the magic of earth and air combining, and some of water too, where elements of air and earth were entwined in it.

Hoor’s arms remained up, his feet melded with the riverbed, straining to move. Unmoving. Arrested by the magic in the music.

A flash of dark feathers caught the periphery of Will’s vision again as he drummed the earth, hard now, feeling nothing but the slam of his palms against the cold ground and the slam of his grieving heart against his chest.

A raven’s cawing voice suddenly accompanied them, making words in a creaking undertone.

No god may truly perish

Great Hoor, you cannot drown

Hoor’s blind-eyed face lifted to the sky, then dropped. A groan vibrated through the air, Hoor’s protest against the song-spell that was undoing his Thames-hewn body.

Surrender to the water

Let slumber take thee down

The mud and bones, the ice and rocks and lumber sagged to a sodden mound. In the centre of the mound was a stone jar sealed in silver and amber. The swell of the jar’s body was carved with runes and symbols. An archer’s bow was etched tightly bound in stylised strands of mistletoe around the centre, spreading up and over the seal.

Wings flapped and a large raven alighted on the ground between Will and Thomas.

‘Drum on,’ it croaked at Will, then cocked its head at Thomas. ‘Your undoing and unwaking song is good. Sing again.’

Thomas sang again. Will beat the rhythm and sang a harmony to make the song stronger.

The raven tapped its beak on the jar, and the amber in it glowed, the silver shone, the stone swelled and thickened, so that the finest crack between seal and jar was rendered seamless.

Then the raven seized the edge of the jar and flapped its wings, tipping the jar over into the turmoil of mud and melting ice. It cawed at the river.

The monstrous shape that Will had earlier sensed roiled strangely under the thinned ice. It heaved, and was gone. Afterwards, Will could not name what he saw. It writhed like a serpent, but was large and thick and scaled, and long ribbons of hair, or weed, had streamed from it. A great, dark maw full of teeth had opened, and shut, and then it was gone. The stone jar, too.

The raven hopped and swept its wings down, rising, then it flew across the frozen Thames, following the shadow of the thing beneath the ice. When it reached London Bridge, the raven came to rest on one of the bridge’s great curved starlings – the rubble-filled bulwarks that protected bridge’s pillars against the current, wayward boats, sundry debris and other things that lived in the muddy shadows.

The raven clicked its beak and made sounds which Will could hear from the riverbank. Now a more trilling call, now a sharp caw, and then a strange warbling.

‘Did that raven truly speak to us?’ Will asked Thomas softly.

‘We’ve sung a god into a pot, and you ask about a talking raven?’

‘It seems the easier discussion,’ confessed Will.

Thomas grinned at him, mad-gleeful. ‘Then yes, brother Will. I believe the raven who is singing to the river spoke to us.’

Will nodded. ‘And the god?’

‘Sung to sleep into a jar, as far as I can tell.’

‘Good. Good. And we’re still alive?’

‘Yes.’

‘However did we manage these miracles?’

Thomas looked down at the instrument he held in his hand. ‘With a yew pipe.’

‘I never even got to use my drum.’

They fell silent again as the raven at the bridge took flight, returning to them. As it approached, Will could already feel the air becoming less cold.

The raven alighted on Will’s drum where it lay on the ground.

‘Hoor was never very clever. You don’t have to be Loki to trick him into his prison,’ said the raven.

‘What are you?’ Will dared to ask.

‘I am Heimdal, charged by Odin to watch over his foolish son. I think he meant my name as a joke,’ said the raven. It tilted its head to stare at them again. ‘Loki’s mischief makes trouble for us all. I imagine it will make more trouble for you, as well.’

‘What kind of trouble?’ Thomas asked, but the bird had launched into the air again.

Above them, the clouds parted and the pale sun gleamed through.

Thomas and Will watched the bird fly east towards the Tower of London keep.

‘Should we warn King Henry that a magic raven is living in his tower?’ Will asked.

‘I think we should leave London, as Heimdal the Raven suggests.’

Will fetched his drum, which he slung awkwardly across his back. The action caused his broken finger to throb painfully, feeling having regrettably returned to it. He cradled his hurt hand. ‘I know a place in Cornwall,’ he said. ‘I don’t know how quickly Loki may learn of today, but I think we can put some miles between us.’

‘The raven could be lying.’

‘It could be trying to help. It helped us once already.’

‘You have a point, Will. Come on, then. Cornwall it is.’

‘Or Ireland,’ said Will, ‘Which is across the sea and therefore further away.’

‘Dickon always wanted to see Ireland,’ said Thomas.

‘Then let’s see Ireland, for Dickon.’

Thomas and Will fell into step, side by side. By the time London had finally stirred to the thawing day, the minstrels had left the city walls far behind.

A few centuries passed and a raven again perched on the tip of the London Bridge starling, watching the elephant crossing the frozen Thames down by Blackfriar’s Bridge.

For over 500 years, the inheritors of Thomas Rowan and William Hawk had come to do this duty – the rebinding of Hoor.

‘I thank you for coming,’ said the raven to the man and woman behind him.

They were all three watching the fair taking place on the ice. Sheep were roasting with a sign declaring them “Lapland mutton”. Two men were charging sightseers to watch the spectacle, plus a shilling for a slice. Elsewhere on the ice, gambling huts and tents for drinking houses were making the most of the novelty. A printing press was turning out terrible poetry on thick paper, boys were playing skittles, and a swing named The Sky Lark was filled with giggling courting couples. The spectacle was new to the eyes of the man and woman with the raven, though they’d read of such things.

The raven had seen it all before.

‘You humans can’t resist dancing on ice,’ it said, ending the pronouncement with a caw made of equal parts admiration and impatience. ‘Your Kings and Queens especially. That fat Henry the Eighth, and then his red-headed daughter. And now here is your paunchy Prince Regent, poking at the ice with no care for what’s beneath it. Anyone would think Erra Pater’s prophecy had never been printed, eh Lily?’

‘We were never sure that was a prophecy,’ said Lily Thorn, drawing her thick winter coat more closely about her. In her left hand she gripped a bundle wrapped in soft leather. Erra Pater’s ridiculous lines of poetry, scribed in 1684, were often analysed in her family’s journals, but no conclusion had ever been reached.

Lily’s companion, equally snugged against the cold, crouched on the broad base of the starling, which created a bulwark for the pylon and foundation of the bridge. A fiddle and bow were tucked under his arm. ‘The lines “and now the struggling sprite is once more come, to visit mortals and foretell their doom” suggests knowledge of the HoorFrost.’

‘Not all songs are magic, Guy, and not all doggerel claiming to foresee is a prophecy,’ countered Lily.

‘Yet here we are again,’ said Guy Hawk drily, ‘trying to keep an ice god asleep in a jar.’

The raven gave the ice below the starling his full attention. ‘Lady Greenteeth doesn’t mean to regurgitate the thing,’ it said,

‘It’s not easy to swallow a god and keep it down. And these two bridges’ – it meant London Bridge and Blackfriars, where the elephant was stepping back onto the banks – ‘slow the river’s flow too much in winter, so it freezes, and frost is Hoor’s element. Makes the runes burn on the vessel. It’s a combination for indigestion.’

There, beneath several feet of ice, was the suggestion of movement. Scales and a sinuous body. Trailing green weeds. Lily wasn’t sure how she could see such a thing, or even if she had. Yet the knowledge was certain. She had inherited more than Thomas Rowan’s minstrel voice and his pipe through the preceding generations.

Guy rose to his feet and brought up the fiddle. Not long ago, he and Lily had been playing out there among the Londoners on the Thames, but only in part for the coin. Coin was good for bread, but applause was good for magic.

His bow across the strings asked a question of the creature below.

The creature moved, rolled. Granted grudging permission.

Lily had unrolled the package and lifted the pipe to her lips. It was made of yew, a wood said to aid witches to speak with other realms. She’d found it useful in quieting ghosts and banishing demons. Guy’s fiddle, birds and vines carved into its body, wasn’t made of anything magical, but magic had been played through it for two hundred years. Magic had been sung into it when Gideon Hawk had made it after the 1608 frost fair, replacing the one broken by that year’s binding.

Gods were indeed hard to keep bound.

Lily, Guy and the raven all saw then how the creature of the mere rolled under the ice, among its coils a glowing thing. Amber light and silver, and runes pulsing. Hoor was waking up.

Lily played the pipe. The raven called a rhythm with its “tok tok tok”. Guy’s fiddle sang around Lily’s fluting notes, the raven’s croaking ones, and he sang.

Hush thy heart, Great Hoor

Tis not yet time to wake

The fate of Asgard waits for you

Sleep on, for London’s sake.

The words changed every time the Thames froze, but the melody persisted, and Hoor was bound afresh. They sealed the cracks in the rune-marked jar that held him. The river’s guardian grudgingly opened her maw and re-swallowed Hoor’s prison, then sank again down through icy waters to burrow into the mud at the foundation of the bridge.

When the verses were sung and the creature with a god in its belly subsided, Lily and Guy put their instruments away. Walking carefully on the ice, they followed the raven back to the banks.

‘We should warn these people off the river,’ Guy noted. ‘The journals say the ice always melts quickly after Hoor’s put back to sleep.’

‘We should get this bridge knocked down so it doesn’t slow the water to ice and keep waking the old bastard,’ croaked the raven.

‘Can we do that?’ Lily asked.

The raven’s feathers ruffled in a shrug. ‘I heard talk of rebuilding the bridge, last time they were clearing ravens from the Tower.’

‘Heard talk or suggested it?’

The raven let loose a sly cackle. ‘Perhaps it’s as you say. Perhaps I’m suggesting other things too. It’s annoying and inconvenient when they clear the ravens out. The Tower is my best view of Hoor’s prison, after all. It’s not a lie to say England may fall if the ravens are made to leave.’

Lily stamped her feet on the banks to shake the snow off her boots. She didn’t look at the raven when she spoke. ‘Are you the same raven all our ancestors write about? Are you Heimdal?’

The raven laughed again. ‘What makes you think I would be?’

She bravely raised her head to look at it. ‘Nothing makes me think you aren’t.’

The raven only laughed again and took flight, returning east to the Tower.

Guy stamped his feet too, seeking warmth. ‘If it’s Heimdal, he’s over 550 years old.’

‘If it’s not Heimdal, it knows a lot about all the other times our family has been called to bind Hoor again.’

‘Perhaps ravens have journals, like we do.’

Lily finished wrapping the pipe in the soft leather again then adjusted her bonnet. ‘Don’t be foolish, Guy.’

Guy only grinned at her. ‘It’s in my nature to be a jester, Lily Thorn.’ He offered her his elbow, though. ‘Let’s go call to these ice- mad revellers to beware of the thaw, and then find a place for supper, shall we?’

Lily, having pulled her gloves on, slipped a hand into the crook of his elbow. ‘Oh God, yes, tea. And then I’ll record today’s binding in the journal.’

‘You’re a conscientious minstrel,’ said Guy, dropping a light kiss on her gloved hand.

‘One of us has to be,’ she teased, but her mouth had dimpled in a smile.

Author’s note: The poem about ‘Silence’ that Will reflects on is Le Roman de Silence, written in the first half of the 13th century but not rediscovered until the 20th.