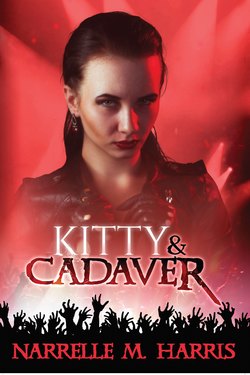

Читать книгу Kitty & Cadaver - Narrelle M Harris - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеMelbourne, Australia, 2014

‘This is it?’ Mr Malone’s gaze took in the four people in front of him. ‘This is the band? I thought you were a six piece?’ The band room manager’s Australian drawl was just this side of rude.

‘A five piece, normally,’ said Laszlo Kantor. ‘I don’t play.’

‘So you are in fact a three piece?’

‘Yes.’

‘Where are the other two?’

‘Dead,’ said Yuka, the drummer, prosaic and defiant.

‘Don’t worry about it. It’s all under control.’

It was totally not under control.

Budapest, Hungary: one week ago

If anything was more ludicrous than five people walking through a city crossroads at 2am, singing and playing instruments, it was their pretension that the bizarre activity was an excuse for vampire hunting.

Laszlo Kantor didn’t tell the patrolling musicians they were preposterous. He’d learned long ago to keep these opinions to himself, especially from preposterous people.

The oddest at the moment was the Swede, Kurt, who had a tablet computer in one hand, open on an app that displayed a keyboard. He played it as he sang into the quiet buildings of this area of light industry.

Water, fire, air and earth

Let no evil cross this line

Weave a web, protect this path

And to their den, evil confine

Six times already they’d sung this song at crossroads all around Budapest’s District 22, including the memorial park of old communist statues where the gigantic, over-earnest figures were ripe for ridicule. Alex had laughed at the derisive nicknames, but they inspired only contempt in Laszlo. He’d known the regime too well to find humour in its graveyard.

‘What are you doing?’ he’d asked Alex at the fourth rendition of the strange song.

‘Hunting,’ laughed Alex, who laughed a lot. ‘Isn’t that right, cicci?’

‘Well, sötnos,’ Kurt replied – full of little endearments, those two, even in the midst of this absurdity – ‘It’s more like herding.’

‘Herding cats.’ said Steve the Texan, the oldest of them.

‘Herding vampires,’ Sal countered.

Kurt sang as he walked the western arm of the crossroad, his voice and the tablet keyboard weaving into the harmonies made by other voices and instruments at the points of the compass. Those at east, north and south sang with their guitars. At the centre of the crossroads, Yuka knelt and beat a tattoo on the street. Laszlo liked the way she played – economical in her movements, beating her sticks like the whole world was her drum.

Kurt and his bandmates converged on Yuka’s spot and the song came to an end.

‘Clear in the west.’ Kurt smiled at Alex, the leader of these talented fools.

‘Clear in the east, cicci,’ Alex said. ‘Sal?’

‘Clear in the north.’

‘Ain’t a whisper in the south, either,’ Steve finished.

Yuka rose to her feet, twirling the sticks in her hands. ‘Clear for blocks around. The earth says they’re hemmed in.’ A twirling stick froze and pointed like a compass in the direction of a derelict factory in Erdõdülõ, by the statue park.

‘Let’s see to this vampire nest,’ Alex said. He shifted his guitar and took Kurt’s hand. ‘You all right with the app or do you want the keytar?’

‘I hate the keytar.’

‘You’re not fond of the app.’

‘I should learn the flute,’ Kurt said. ‘Much more portable.’

‘So you don’t like my idea of putting rollers on a baby grand?’ Steve teased.

‘You people,’ Laszlo said in disgust, forgetting his rule about not expressing his opinions. This cavalier stupidity was, Alex claimed, an investigation into the unsolved murders and disappearances of a dozen people in the last month.

‘What’s your beef ?’

‘People have vanished, Steve, and all you do is talk nonsense. Vampires and wheels on pianos.’

‘Only one of those things is nonsense,’ Alex said.

‘Wheels on a piano,’ Kurt scoffed. ‘It would roll away every time I played prestissimo.’

‘You are not funny.’ The disappearances reminded Laszlo too much of the humourless secret police in the Bad Old Days for him to find even black humour in the situation.

Yuka laid a hand on his arm. ‘It isn’t funny. What we do is not funny. We only pretend it’s a game. Do you understand?’

He understood very well. At the blackest times, ridiculousness was a lifeline, but twenty years later, he was still too heartsore to find relief in banter. ‘People who disappear in Hungary don’t think it’s a game. Does this talk of vampires keep your heart light?’

‘No,’ she said with grim sincerity. ‘Vampires are only darkness.’

‘You don’t need to come with us for the next bit,’ Alex said. ‘We’ll get what we need from the van and meet you later.’

Kurt took out his phone and made a call as they walked to the parked van. ‘Harper? How is she? What? But why? All right, all right.’ A moment later Kurt spoke in a tiny sing-song voice. ‘Gretel! Little Gretchen! Why do you cry for Harper? Can’t you sleep, bubba?’

‘What’s she doing awake?’ Alex demanded, nipping across to walk with Kurt.

‘Pappa and Dadda are coming home soon!’ Kurt held the phone out to Alex, who made kissy noises through the speaker. ‘Pappa loves you! And Dadda loves you! Oh, Harper, hello again. We have one more song tonight and we’re done. Sing Gretchen her lullaby; that always works.’

Laszlo ambled along behind the group, alert to the chill of the night, the scent of loam from the nearby garden centre and the faint odour of ammonia given off by the water treatment plant on the edge of the Chamber Forest. A flurry of alarmed squawking rose up from the forest to the north and fell suddenly silent.

Even the birds weren’t happy with these strange activities.

Sal was reading from the notebook he carried everywhere, its pages well worn and cover marked with water stains and smudges of ink. His lips moved and he muttered to himself a line Laszlo recognised as Marcus Aurelius. A man when he has done a good act, does not call out for others to come and see, but he goes on to another act, as a vine goes on to produce again the grapes in season.

‘I want my djembe,’ Yuka said, ignoring the young fathers chatting with their infant. Laszlo had the impression Yuka was agitated by the call. In fact, everyone seemed uncomfortable while Alex and Kurt talked to their babysitter.

Sal shoved the book back in his pocket. ‘Not the den-den? You can use the handle as a stake.’

‘Better sound from the djembe,’ Yuka said as they closed in on the van. ‘Better not to get close enough for staking.’

‘Sleepytimes now, älskling,’ Kurt was cooing into the phone. ‘There’s our good gi-aaah!’

Kurt shrieked and disappeared up, up so fast, up. Alex, almost as fast, leapt to wrap his arms around Kurt’s legs.

‘No!’

Sal leapt to hang on to Alex’s legs and all three were lifted high into the air, while the thing above them made an unholy screech and beat its giant wings, wafting down a musky animal stink.

Steve, instead of joining the kite-tail of people, whipped his guitar into position and began to play. Yuka took a more direct approach: she leapt and clambered up the ladder of bodies to the beast, to stab the stick into one of the great taloned feet that gripped Kurt’s shoulders. She drew blood and the flying creature screeched in rage.

Laszlo stared in shock and wonder at the thing he could barely comprehend. A griffmadár, its shaggy body and hindquarters that of a lion, the forequarters and head of the royal turul, the mythological falcon. Its giant wings beat, its talons dug deeper into Kurt’s shoulders. Kurt screamed and twisted, trying to free himself. Blood from the talons in his flesh, and from Yuka’s drum stick in the beast’s foot, dripped onto Alex’s face below.

‘Cicci!’ Alex shouted, desperately hanging on.

Steve was crying out for everyone to let go. The griffmadár was rising so high that a fall would be damaging, and soon fatal. Besides, the weight of all of them on Kurt’s body was making the claws tear deep furrows into his flesh.

The beast screamed again, rolled in the air and shook Sal off easily. Yuka clung so tight, with her drum stick buried in the thing’s leg, that it took longer but she was thrown free soon after. Alex hung on tight for three turns before he was thrown clear.

The monster’s triumphant screams mingled with Kurt’s yells of pain as the griffmadár flew away into the night, in the direction of Erdõdülõ. Those it had shaken free lunged towards the van.

Alex shoved Laszlo out of his way and opened the back of the van to rummage among the contents.

Laszlo was struck with awe and horror. ‘What was that?’

Nobody answered.

‘How the hell did that get past the wards?’ Sal snarled.

Yuka, muttering curses in her native Japanese, climbed past Alex into the van to find her djembe.

Steve had retrieved Kurt’s phone, which had smashed against the road. ‘We warded against evil, not griffins,’ he said.

‘Aren’t… aren’t griffmadár evil?’ Laszlo stammered.

‘Depends on the griffin. Seems this one’s made a deal with Prince Vladimir.’ Steve held his own phone to his ear and turned away from Laszlo to speak urgently into it. ‘Harper, it’s gone to hell. Get Gretel out of there. Not in the morning. Now. Go to London, then home if you don’t hear from me again.’

Before Laszlo could ask any more questions he didn’t really want answered, Alex shoved a violin into his hands.

‘Can you play?’ Alex’s eyes were feverish bright with fury and fear. ‘I saw you eyeing this off when we played at Dürer-kert.’

Laszlo twitched. The pub show he’d organised on Tuesday seemed suddenly of an alien world. ‘I used to.’

‘Good enough.’ Alex thrust the venerable instrument into his hands.

‘I don’t know your songs.’

‘The violin does.’

Laszlo’s confusion doubled and doubled again. Sal was in the driver’s seat; Steve and Yuka were in the rear. Alex impatiently dragged Laszlo by the arm to the front door, and Laszlo resisted. Alex was paying him to organise gigs, be a local guide and interpreter, and tolerate the crazy. He suspected he wasn’t being paid enough.

‘What are we doing?’

‘We’re getting my Kurt back and putting down that nest of leeches for good.’

‘We are going to fight a griffin?’

‘We’re fighting vampires,’ Alex corrected, his grin savage. ‘Are you in or out?’

Laszlo held the violin and his heart pounded harder than ever.

Vampires, in his city. And a violin, a reminder of his sins. Rising out of his panic and terror was, strangely enough, a surge of hope.

‘In. What do I have to do?’

‘Draw the bow across the strings. The violin will do the rest. Come on.’

‘You go right to their front door?’ Laszlo was horrified.

‘We hemmed them in with the wards,’ Alex explained. ‘They know they can’t escape.’

‘It is why they sent the griffin,’ Yuka said, as though that were obvious. ‘There is no escape. Only revenge.’

‘But surely we should… sneak up?’ Laszlo said.

‘Bit late for stealth anyway. They know we’re coming,’ Steve said.

‘Just because they lure you, you don’t have to follow.’

‘They’ve got Kurt,’ Alex said. And that was that.

The band known as Rome’s Burning piled out of the van in front of the factory where the vampires had been trapped by the series of spells in crossroads all around the district. They took up their instruments. Laszlo tucked the violin under his chin and listened to the music building up around him, wondering when he should play, and what he would play when the time came, and whether he really believed what was happening.

The melody that wove around the five of them as they spread out along the street softened their footfalls and made the trees rustle as they passed.

They were greeted by Vladimir, Prince of Vampires, at the threshold of the abandoned factory he had made into a home. He held Kurt by a fistful of bloodied shirt. The metallic smell of too much blood loss was noticeable.

‘You don’t give up, do you, Torni?’

‘No,’ Alex said in almost his old, flippant voice. ‘Not when you go around eating people and recruiting the occasional unwilling survivor into your pack.’

‘Not a pack. My House. And I warned you what would happen if you interfered.’

‘Interfering’s what we do. Still, let Kurt go and we’ll parlay.’

Vladimir’s answer was to tear Kurt’s shirt to better reveal the ugly bite in Kurt’s throat. Human blood mingled with a darker substance oozed from it. Laszlo heard the moment when Alex’s breath stopped.

‘Your beloved Kurt belongs to my House now.’ Vladimir laughed, the blood between his teeth, as Kurt convulsed at his feet. ‘Burn my House,’ he said, ‘and you burn your beloved.’

‘Let him go.’

‘And we shall parlay?’

‘And I won’t burn you all to cinders.’

‘You will never take us all.’

Kurt shuddered one last time. Then he rose smoothly to his feet and even Laszlo, who hardly knew the man, knew that this was no longer Kurt.

‘Alex. Sötnos,’ said the monster with Kurt’s face. ‘You look good enough to eat.’

Alex’s face drained of colour. His mouth made the shape, Kurt, but he had no voice. He grit his teeth and raised his arm as a signal.

‘No quarter,’ he snarled, and plucked the strings of his guitar for the opening notes. The destruction began.

Come to me sun

I beg of thee a whisper of your breath

Come to me sun

I beg of thee a tongue of flame

To ignite the world where I name

Laszlo drew his bow across the strings and played the tune without knowing how he knew it.

Rome’s Burning advanced on the factory and lived up to their name. The door frame ignited. Vladimir fled, leaving Kurt to his own devices. Kurt swiftly disappeared inside the building.

The band sang an inferno and the front wall burned so brightly Laszlo thought their instruments would ignite from the heat. Instead, the wall caved in.

Shrieking, the griffin rose from the fire and flew into the night, a great egg in its talons. Later, the survivors would conclude the griffin had abducted Kurt in return for its offspring. At this point, however, the griffin wasn’t important.

Wooden features and plaster burst into flames all around them. Even bricks burned.

Vampires began to flee the burning building, like cockroaches when the light flicks on, but they didn’t get far. Sal was singing something counter to the main melody (green and growing things, defend the earth) and trees responded to his call.

From every thick-trunked tree to every sapling, roots and branches curled and whipped and became spears, staking the mostly newly made vampires who couldn’t avoid the writhing mass of weapons. Stabbed with wood through the heart, they dissolved into ash.

Alex stormed through the front of the building and his band followed without hesitation, Laszlo with them.

Within, glass shattered; floorboards cracked. Monsters, trapped between flame and wood, screamed as they died. The air burned with no fuel but the song that made it.

Even water burns

Even the sky

Let the flames scorch the earth and purify

Where I guide.

Alex choked short and Laszlo saw Kurt loom out of the smoke, snatch Alex by the throat and disappear. He cried out a warning and the others drew closer together, still singing. In turns, they took cloves of garlic from pockets and strewed them about the room.

‘Don’t stop playing!’ Steve shouted.

Laszlo didn’t; he couldn’t. It felt much more like the violin was playing him – drawing on his long-abandoned skills and guiding his fingers through music he’d never known.

In that Erdõdülõ vampire nest, Laszlo’s bow slid across the strings, eliciting notes sweet and pure and relentless, which scorched the air. The firestorm never touched him or his fellow musicians. Flames licked the walls, ate the ceiling, melted the glass. Transformed the vampires into pillars of blue fire.

Prince Vladimir was cornered in the factory’s former workroom, stripped of its equipment, leaving only the pitted concrete floor and windows that had cracked in the heat. One or two feathers and a gaping hole in the ceiling showed that this was where the griffin’s egg had been held and liberated.

Vladimir laughed. ‘I took your House from you. Kurt Stefan is mine. Alex Torni is mine. Kill me if you like. I still win.’

Rome’s Burning sang. The dozens of branches and roots of a single tree burst through the shattered panes and speared Vladimir’s body through. He laughed even as he choked; even as his heart was pierced, even as he burned.

The band turned from the vampire prince as he was reduced to ash, and moved through the factory to finish the job. The stench of old blood, of burned metal and brick, of flesh, was everywhere.

When nothing else moved in the ember-filled darkness, Rome’s Burning sang the fire into submission.

Come to me, firestorm

Come to me, burning brook

Come to me, stones on fire

Come to me, burning air

Come to me, flames

Come to me, molten earth

I beg thee return to heart and sun

I beg thee be quenched, now my work is done.

Naturally, they searched for Alex. They found him huddled and bleeding under tin from the fallen roof, his throat torn. Sal cradled the dying man in his arms.

‘Kurt.’ Alex was sobbing. ‘They killed my Kurt.’ He turned blazing eyes on them. ‘You killed my darling. He’s dead. You burned him.’

‘He wasn’t Kurt any more,’ Steve said, as gently as he could.

Alex, on the cusp of human and monster, sobbed again. ‘I’m not Alex any more. Soon. Oh my god, oh my god. Steve. Steve?’

Steve’s hands trembled. ‘Okay. Shh, Alex. I’ll do it.’

Not-Alex glared at him again. ‘Yes. You’re good at it. Watching the people you love die.’

‘Don’t,’ Steve begged.

‘Sorry, sorry, sorry,’ muttered the human part of their friend.

Sal stroked Alex’s hair. ‘It’s all right, Steve. I’ll do it.’

Steve tried to protest, but he gave in when Sal insisted. Anyone could see that Steve didn’t have the heart to insist.

‘You don’t have to stay,’ Sal said.

‘Oh go on,’ Not-Alex jeered. ‘Watch. It’ll be educational.’ Then he looked horrified and cried tears of blood.

Steve gave Sal all the garlic remaining in his pockets. Yuka, too. Laszlo didn’t have any garlic – he’d thought the whole thing nonsense.

‘Laszlo,’ Alex rasped.

‘I’ll take care of them,’ Lazlo found himself promising.

Alex laughed. ‘Good. They need a roadie.’

Sal took out a bowie knife and held it to Alex’s throat. ‘Wait outside.’

‘Save me,’ Alex whispered to Sal as the others left them among the ashes.

‘Of course. You saved me, didn’t you?’

When Sal joined the others outside, he looked like his soul had gone with Alex’s into the beyond.