Читать книгу Naive Art - Nathalia Brodskaya - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

I. Birth of Naive Art

Discovery – the Banquet in Rousseau’s Honour

ОглавлениеImpressionism actually had more of an effect upon art in general than it initially seemed to. The rebellion against the ‘tyranny’ of the old and traditional system of Classicism that it fomented – the establishing of the principle of freedom in content, form, style and context – led to a broadening of the whole concept of ‘art’ itself.

Janko Brašic, Dance in Circle next to the Church.

Private collection.

Towards the end of the Impressionist ‘period’ – so much so that they are forever labelled Post-Impressionist – Paul Gauguin and Vincent Van Gogh joined the Impressionists’ ranks. What they lacked in training they made up for in hard work. Indeed, only in the very early pictures of Gauguin is any deficiency of skill evident. And when Van Gogh arrived in Paris in 1886, no one expressed any doubts as to his worthiness to take his place among the international clique of artists in the community in Montmartre which by that time had existed there for nigh on a century. Perhaps inevitably, the pair did not, however, find acceptance in the salon dedicated to the most classical forms of contemporary art. They were nonetheless able to exhibit their works to the public, especially since Parisian art-dealers – marchands – were opening more and more galleries. In 1884 the Salon des indépendants was launched. This had no selection committee and was set up specifically to put on show the works of those artists who painted for a living but were yet unable or unwilling to meet the requirements of the official salons. Of course there were many such artists – and of course among the overwhelming multiplicity of their mostly talentless works it was not always easy to identify those pictures that were exceptional in merit.

Henri Rousseau served as a customs officer at the Gate of Vanves in Paris. In his free time he painted, sometimes on commission for his neighbours and sometimes in exchange for food. Year after year from 1886 to 1910 he brought his work to the Salon des indépendants for display, and year after year his work was exhibited with everybody else’s despite its total lack of professional worth. Nevertheless he was proud to be numbered among the city’s artists, and thoroughly enjoyed the right they all had to see their works shown to the public like the more accepted artists in the better salons.

Emma Stern, Self-Portrait, 1964.

Oil on canvas, 61 × 46 cm.

Clemens-Sels-Museum, Neuss.

Sava Sekulic, Portrait of a Man with Moustache.

Mixed media on cardboard, 45 × 48 cm.

Galerie Charlotte, Munich.

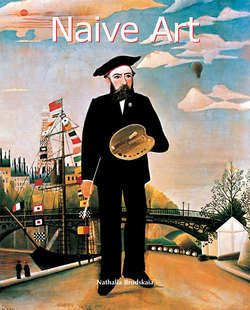

Rousseau was among the first in his generation to perceive the dawn of a new era in art in which it was possible to grasp the notion of freedom – freedom to aspire to be described as an artist irrespective of a specific style of painting or the possession or lack of professional qualifications. His famous picture (now in the National Gallery, Prague), dated 1890 and entitled Myself, Portrait-Landscape. rather than the comparatively feeble self-portrait, reflected that selfsame ebullient self-confidence that was a characteristic of his, and established the image of the amateur artist taking his place in the ranks of the professionals. “His most characteristic feature is that he sports a bushy beard and has for some considerable time remained a member of the Society of the Indépendants in the belief that a creative personality whose ideas soar high above the rest should be granted the right to equally unlimited freedom of self-expression”,[7] was what Rousseau wrote about himself in his autobiographical notes.

It just so happened that Pablo Picasso visited a M. Soulier’s bric-a-brac shop in the Rue des Martyrs on a fairly regular basis: sometimes he managed to sell one of his pictures to M. Soulier. On one such occasion Picasso noticed a strange painting. It could have been mistaken for a pastiche on the type of ceremonial portraits produced by James Tissot or Charles-Emile-Auguste (Carolus-Duran) had it not been for its extraordinary air of seriousness. The face of a rather unattractive woman was depicted with unusually precise detail given to its individual features, yet with a sense of profound respect for the sitter. Somehow the female figure – clothed in an austere costume involving complex folds and creases and surrounded by an amazing panoply of pansies in pots on a balcony, observing a prominent bird flying across a clouded sky, and holding a large twig in one hand – looked for all the world like a photographer’s model as posed by an amateur photographer, but still was hauntingly realistic and arresting. The artist was Henri Rousseau. The price was five francs. Picasso bought it and hung it in his studio.

In point of fact, it was not only Picasso who was interested in Rousseau’s work at this time. The art-dealer Ambroise Vollard had already purchased some of Rousseau’s paintings, and the young artists Sonja and Robert Delaunay were friends of his, as was Wilhelm Uhde, the German art critic who organised Rousseau’s first solo exhibition in 1908 (on the premises of a Parisian furniture-dealer). But it was Picasso who, with his friends, decided in that same year to hold a party in Rousseau’s honour. It took place in Picasso’s studio in the Rue Ravignan at a house called the Bateau-Lavoir. Some thirty people turned up, many of them naturally Picasso’s friends and neighbours, but others present included the critic Maurice Raynal and the Americans Leo and Gertrude Stein.

Decades later, during the 1960s, by which time the ‘Rousseau banquet’ had become something of a legend in itself, one of the guests – the naive artist Manuel Blasco Alarcon, who was Picasso’s cousin – painted a picture of the event from memory. Henri Rousseau was depicted standing on a podium in front of one of his own works, and holding a violin. Seated around a table meanwhile were various guests whom Alarcon portrayed in the style of Picasso’s Gertrude Stein and Henri Rousseau’s Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin.

Marie Laurencin, The Italian, 1925.

Oil on canvas.

Former collection of Albert Flamert.

Henri Rousseau, also called the Douanier Rousseau, Myself, Portrait-Landscape, 1890.

Oil on canvas, 143 × 110 cm.

Národní Galerie, Prague.

Henri Rousseau, also called the Douanier Rousseau, Guillaume Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin, 1909.

Oil on canvas, 200 × 389 cm.

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Henri Rousseau, also called the Douanier Rousseau, Horse Attacked by a Jaguar, 1910.

Oil on canvas, 89 × 116 cm.

The Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

Ivan Rabuzin, Flower on the Hill, 1988.

Watercolour on paper, 76 × 56 cm.

Rabuzin Collection, Kljuc.

Elena A. Volkova, Young Girl from Sibera.

Private collection.

At the banquet all those years previously, the elderly ex-Douanier Rousseau (then aged sixty-four, having retired from his customs post at the age of forty-one in order to concentrate on art) found himself surrounded mainly by vivacious young people intent on having a good time but in a cultural sort of way. Poems were being recited even as supper was being eaten. There was dancing to the music of George Braque on the accordian and Rousseau on the violin – in fact, Rousseau played a waltz that he had composed himself. The party was still going strong at dawn the next day when Rousseau, emotional and more than half-asleep, was finally put into a fiacre to take him home. (When he got out of the fiacre, he left in it all the copies of the poems written for him by Apollinaire and given to him solicitously as a celebratory present.) Even after he had departed, the young people carried straight on with the revels. Only later in the memories of the people who had been there did this ‘banquet’ stand out in their minds as a truly remarkable occasion. Only then did individual anecdotes about what happened there take on the aspect of the mythical and the magical. Quite a few were to remember a drunken Marie Laurencin falling over on to a selection of scones and pastries. Others indelibly recalled Rousseau’s declaration to Picasso that “We two are the greatest artists of our time – you in the Egyptian genre and me in the modern!”[8]

Mihai Dascalu, The Broken Bridge.

Oil on canvas, 50 × 70 cm.

Private collection.

This statement, arrogant as it might have seemed at the time to those who heard it, was by no means as ridiculous as some of those present might have supposed. As the story of the ‘Rousseau banquet’ spread around the city of Paris and beyond, the people who had been there began in their minds to edit what they had seen and heard in order to present their own versions when asked. Six years later, in 1914, Maurice Raynal narrated his recollections of it in Apollinaire’s magazine Soirées de Paris. Later still, Fernanda Olivier and Gertrude Stein wrote it up in their respective memoirs. In his Souvenirs sans fin, André Salmon went to considerable pains to point out that the ‘banquet’ was in no way intended as a practical joke at Rousseau’s expense, and that – despite suggestions to the contrary – the party was meant utterly sincerely as a celebration of Rousseau’s art. Why else, he insisted, would intellectuals like Picasso, Apollinaire and he himself, André Salmon, have gone to the trouble of setting up the banquet in the first place? This was too much for the French artist and sculptor André Derain who publicly riposted to Salmon, “What is this? A victory for con-artistry?”[9] Later, he was sorry for his outburst, particularly in view of the fact that he rather admired Rousseau’s work, and only quarrelled with Maurice de Vlaminck, one of his best friends, when Vlaminck was unwise enough to suggest in an interview with a journalist that Derain was dismissive of Rousseau’s work.

Mihai Dascalu, Close to the Windmill.

Oil on canvas, 80 × 100 cm.

Private collection.

Only a few years later, and there was actually a squabble about who had ‘discovered’ Rousseau. The critic Gustave Coquiot in a book entitled Les Indépendants expressed his exasperation at hearing people say that it had been Wilhelm Uhde who had introduced Rousseau and his work to the world. How was it, he asked indignantly, that some German fellow could claim in 1908 to present for the first time to the Parisian public a Parisian artist whose work had been on show in Paris to those who wanted to see it ever since 1885 or earlier?[10]

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента. Купить книгу

7

Le Douanier Rousseau, published by the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, 1985, p.262

8

Le Banquet du Douanier Rousseau, Tokyo, 1985, p.10

9

A. Salmon, Souvenirs sans fin, deuxième époque, 1908–1920, Gallimard, Paris, 1956, p.49

10

G. Coquiot, Les Indépendants, 1884–1920, Librairie Publishing, p.130